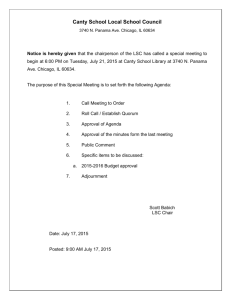

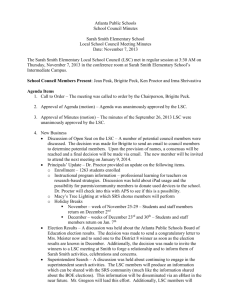

LSC Aff file v1

advertisement