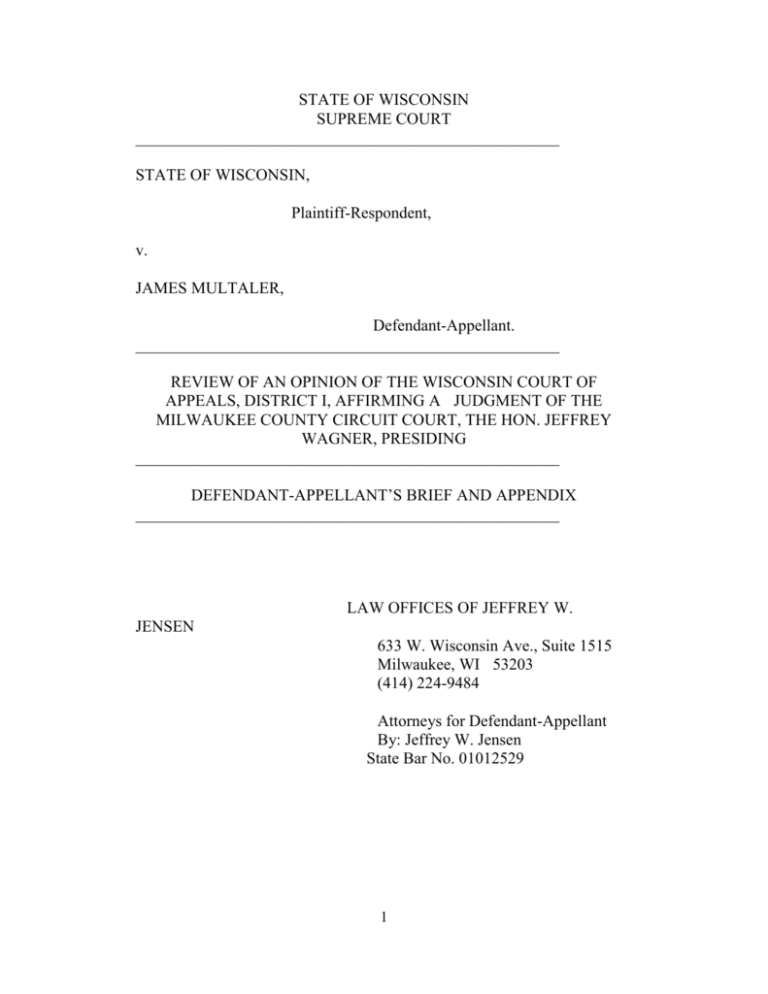

STATE OF WISCONSIN

SUPREME COURT

____________________________________________________

STATE OF WISCONSIN,

Plaintiff-Respondent,

v.

JAMES MULTALER,

Defendant-Appellant.

____________________________________________________

REVIEW OF AN OPINION OF THE WISCONSIN COURT OF

APPEALS, DISTRICT I, AFFIRMING A JUDGMENT OF THE

MILWAUKEE COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT, THE HON. JEFFREY

WAGNER, PRESIDING

____________________________________________________

DEFENDANT-APPELLANT’S BRIEF AND APPENDIX

____________________________________________________

LAW OFFICES OF JEFFREY W.

JENSEN

633 W. Wisconsin Ave., Suite 1515

Milwaukee, WI 53203

(414) 224-9484

Attorneys for Defendant-Appellant

By: Jeffrey W. Jensen

State Bar No. 01012529

1

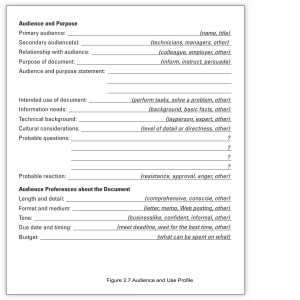

TABLE OF AUTHORITY

Cases

Andreson v. Maryland, 427 U.S. 463 (1976) ............................... 7

Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U.S. 108 (1964) ......................................... 10

Bast v. State, 87 Wis.2d 689, 275 N.W.2d 682 (1979) ............... 7

Bastida v. Henderson, 487 F.2d 860 (5th Cir. 1973) .................. 8

Cresci v. State, 89 Wis.2d 495, 278 N.W.2d 850 (1979) .............. 18

Harrell v. State, 88 Wis.2d 546, 277 N.W.2d 462 (Wis.App. 1979) 15

Leroux v. State, 58 Wis.2d 671, 207 N.W.2d 589 (1973) ............ 10

Lincoln Savings Bank, SA v. Wisconsin Department of Revenue,

215 Wis. 2d 430, 573 N.W.2d 522 (1998) .................................... 20

Rice v. Wolff, 513 F.2d 1280, 1285 (8th Cir. 1975) ..................... 7

State v. A.H., 211 Wis. 2d 561, 566 N.W.2d 858

(Ct. App 1997) ............................................................................... 19

State v. Anderson, 149 Wis.2d 663, 439 N.W.2d 840 (Wis.App. 1989)

6

State v. Benoit, 83 Wis.2d 389, 399-400, 265 N.W.2d 298, 303 (1978)

7

State v. Carol M.D., 198 Wis.2d 162, 542 N.W.2d 476 (Ct.App.1995)

18

State v. Davis, 171 Wis.2d 711, 492 N.W.2d 174

(Ct.App.1992) ................................................................................ 18

State ex rel. White v. Simpson, 28 Wis. 2d 590, 137 N.W.2d 391 (1965)

9

State v. Harris, 256 Wis. 93, 39 N.W.2d 912 (1949) ................... 10

2

State v. Hubbard, 206 Wis.2d 651, 558 N.W.2d 126 (Wis.App. 1996)

17

State v. J.E.B., 161 Wis. 2d 655, 469 N.W.2d 192

(Ct. App. 1991) .............................................................................. 18

State v. Johnson, 158 Wis. 2d 352, 463 N.W.2d 352 (Ct. App. 1990) 18

State v. Multaler, 2001 WL 641802 (Ct. App. 2001) ................... 10

State v. Princess Cinema of Milwaukee, Inc., 96 Wis. 2d 646,

292 N.W.2d 807 (1980) ................................................................. 18

State v. Secrist, 224 Wis.2d 201, 589 N.W.2d 387 (1999) ........... 12

State v. Warren, 229 Wis.2d 172, 599 N.W.2d 431

(Ct. App. 1999) .............................................................................. 19

Steele v. United States, 267 U.S. 498 (1925) ................................ 9

Stone v. Powell, 428 U.S. 465 (1976) ........................................... 7

United States v. Boyd, 422 F.2d 791 (6th Cir. 1970) ................. 7

United States v. Brinklow, 560 F.2d 1003 (10th Cir. 1977) ......... 7

United States v. Damitz, 495 F.2d 50 (9th Cir. 1974) .................. 7

United States v. Hyde, 574 F.2d 856 (5th Cir. 1978) ................... 8

United States v. Singleton, 125 F.3d 1097 (7th Cir. 1997) .......... 10

United States v. Steeves, 525 F.2d 33 (8th Cir. 1975) .................. 8

United States v. Tucker, 404 U.S. 443(1972) ............................... 18

United States v. Weinrich, 586 F.2d 481 (5th Cir. 1978) ............. 7

Statutes

Sec. 948.12, STATS. ........................................................................ 2

3

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT ON ORAL ARGUMENT AND

PUBLICATION .................................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE ....................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND ....................................... 2

II. FACTUAL BACKGROUND .............................................. 3

ARGUMENT ................................................................................... 6

I.. THE AFFIDAVIT SUBMITTED IN SUPPORT OF THE

APPLICATION FOR A WARRANT TO SEARCH MULTALER’S

HOME ON ARROW STREET WAS INSUFFICIENT TO

ESTABLISH PROBABLE CAUSE AND INCLUDED FALSE

INFORMATION WHICH WAS MATERIAL TO THE COURT’S

PROBABLE CAUSE DETERMINATION ....................... 6

II. THE INFORMATION WAS MULTIPLICITOUS ... 16

CONCLUSION ............................................................................. 23

APPENDIX

5

STATEMENT ON ORAL ARGUMENT AND PUBLICATION

The issues presented by this appeal are complex and, therefore, oral

argument will materially assist the court in deciding the matter. Likewise,

the issues are of statewide importance and, therefore, publication is

recommended.

ISSUES PRESENTED

I. Whether, based upon the affidavit of a police detective, probable

cause existed in 1998 for the issuance of a search warrant to search

Multaler’s home for evidence of a series of strangulation deaths of young

women in the Milwaukee area which occurred in the early 1970s where:

A. The existence of probable cause to search depended upon there

being probable cause to believe that Multaler was the killer of the women;

and,

B. There being probable cause to believe that Multaler was a

“serial killer”; and,

C.

There being probable cause to believe that Multaler would

still possess items of personal property belonging to the victims after

twenty-four years despite the fact that Multaler had been incarcerated in

prison for nearly ten of those twenty-four years.

The issue was presented to the Court of Appeals in the following

manner:

I. Whether the affidavit presented in support of the state’s application

for a warrant to search Multaler’s home established probable cause to

believe that Multaler was in possession of the items sought and that the

items were likely to be found in the area searched.

ANSWERED BY THE TRIAL COURT: Yes.

The Court of Appeals held that the affidavit of the investigating

detective did establish probable cause to search Multaler’s home.

While

recognizing that, in some instances, the facts were more than twenty years

old, the majority held that, “[T]he ‘old’ evidence was not stale; it had been

revived by (the detective’s) . . . fresh analysis of ‘the nature of the criminal

activity’ and the nature of the evidence that, Hanrahan reasonably

believed, remained at Multaler’s residence.” (Opinion p. 14).

6

II. Whether the criminal complaint filed against Multaler alleging

twenty-eight counts of possession of child pornography was multiplicitous

for the reason that the state charged an additional count for each

pornographic digital image found on two computer diskettes seized from

Multaler’s home.

ANSWERED BY THE TRIAL COURT: No.

This issue was presented to the Court of Appeals in an identical

fashion and the court held that the criminal complaint was not

multiplicitous.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND.

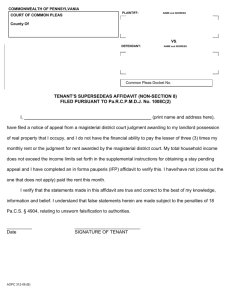

The defendant-appellant in this case, James Multaler (hereinafter

referred to as “Multaler”), was originally charged with numerous counts of

possession of child pornography contrary to sec. 948.12, STATS. 1 The

complaint alleged that police raided Multaler’s home with a search warrant 2

and during the process of the search discovered two computer diskettes

which contained images of children engaged in explicit sexual acts. The

state charged one count for each separate image found on the diskette. (R:2)

Multaler entered pleas of not guilty to all counts. He then filed a

motion suppress all evidence on the grounds that the affidavit filed in

support of the application for the search warrant failed to establish probable

cause to believe that the items would be located in Multaler’s home. (R:8).

The parties filed a number of briefs on the issue and the court eventually

denied the motion by written decision. (R:43-3; R:12 attached hereto as

Exhibit B).

1

948.12 Possession of child pornography. Whoever possesses any undeveloped film, photographic negative,

photograph, motion picture, videotape or other pictorial reproduction or audio recording of a child engaged in

sexually explicit conduct under all of the following circumstances is guilty of a Class E felony:

(1) The person knows that he or she possesses the material.

(2) The person knows the character and content of the sexually explicit conduct shown in the material.

(3) The person knows or reasonably should know that the child engaged in sexually explicit conduct has not attained

the age of 18 years.

2

The search warrant was issued based upon a finding of probable cause by a judge in Racine County that Multaler’s

home might contain evidence of a series of strangling murders in the Milwaukee and Racine area during the 1970’s.

7

The information was later amended to allege twenty-eight counts

and Multaler pleaded no contest pursuant to Alford (i.e. maintaining his

innocence) to all twenty-eight counts (R:47-2). The court sentenced

Multaler to the maximum of two years in prison on each count,

consecutive, for a total of fifty-six years in prison. (R:24; R:48-45).

Multaler then filed postconviction motions alleging that the criminal

complaint was multiplicitous because it alleged an additional count for each

digital image contained on the diskettes. He also alleged that the sentence

imposed by the court was unduly harsh. The court denied both motions by

memorandum decision without a hearing. (R:34).

Multaler timely filed a notice of appeal to this court.

II. FACTUAL BACKGROUND

In May of 1998 police detectives for the City of Racine were still

attempting to solve a series of strangulation murders of young women

which occurred on Milwaukee’s south side in 1974-1975. Three of the

bodies were located near the Root River in Racine County. (R:8; affidavit

attached as Exhibit C).

On May 18, 1998 Investigator John Hanrahan signed an affidavit3 in

support of an application made to the Racine County Circuit Court for a

warrant to search Multaler’s residence at 1858 W. Arrow Street in the City

of Milwaukee. The affidavit may be summarized as follows.

In a relatively short period of time in 1974 four young women were

found dead in Milwaukee County and in Racine County. In two of the

deaths it was determined that the cause was “ligature strangulation.” (i.e.

the use of a cord or some similar implement to strangle the victim).

Three of the women were found near the Root River in Racine County in a

similar condition with their clothing pulled up over their breasts. In none

of the cases was there evidence of sexual assault. According to Hanrahan,

each of the victims were missing items of personal property which,

according to witnesses interviewed by Hanrahan, the victims were very

likely to have had on their person at the time of their deaths.

Police also

found at one of the scenes a “bungee” cord which had one of its hooks bent

into an “L” shape.

Unless otherwise noted, all of the following facts are taken from Investigator Hanrahan’s affidavit which

is attached hereto as Exhibit C

3

8

Additionally, the affidavit recited that in 1975 Debra Whitaker was

traveling alone in her vehicle on I-94 in Milwaukee County when a man

approached her from behind in a vehicle and through a loudspeaker ordered

her to pull over claiming that he was a state police officer. Whitaker

pulled over but when she questioned the man he pulled pistol and forced

her into his automobile. He handcuffed her to the steering wheel.

Whitaker asked the man to turn off the headlights of her car and when the

man did so she drove away in his vehicle. She immediately located a

police officer who went back to the scene. Multaler was arrested and

convicted of the kidnapping of Whitaker.

Hanrahan also alleged that he interviewed a former girlfriend of

Multaler, Mary Fairbanks, who claimed that she dated Multaler in 1970 and

that in order to become sexually aroused Multaler needed to place his

fingers on her neck until she lost consciousness. Fairbanks also claimed

that she had seen Multaler with a bungee cord with one of its hooks bent

into an “L” shape. Another former girlfriend, Audrey Novak, stated that

she dated Multaler in 1975 and that it was his habit to choke her during

sexual intercourse and that on several occasions she lost consciousness.

Finally, the affidavit also alleged that police interviewed Multaler’s current

wife, Patricia, in 1975 and that she also told police that Multaler choked her

during sex.

The affidavit then restates at some length the status of the police

investigation in 1975. Hanrahan claims that police interviewed Multaler

regarding one of the victims, Wendy Gail Brown, and that Multaler

admitted to being with her on the night she was murdered but that he

claimed not to know what happened to her. Additionally, the affidavit

alleges that Multaler kept a scrap book of news reports concerning the

victims of the so-called “South Side Strangler.” Hanrahan claimed that

the Milwaukee District Attorney received in the mail a copy of a newspaper

article detailing Multaler’s arrest for the Whitaker kidnapping with a

handwritten note reading, “This man is the South Side Killer (7 Mile Rd.)

He has raped 36 girls”. According to the affidavit, the handwriting was

analyzed and determined to be Multaler’s.

The affidavit concludes by reciting that Hanrahan has read a number

of books concerning serial killers and that he has attended a number of

symposia on the topic. Based on this research, Hanrahan alleged that serial

killers will frequently keep newspaper clippings and personal items from

their victims and at great risk to themselves maintain them.

According

the books, this is to permit the killer to relive his experiences.

9

Significantly, the affidavit alleges that, “James I. Multaler resides at

1858 West Arrow Street in the City of Milwaukee, and has resided there

since this investigation. Your affiant states that Milwaukee Police reports

indicate that the suspect has resided at the same residence with his wife and

daughter for over twenty years.” (paragraph 76).

At a motion hearing Multaler established that he had not lived at that

address with his wife for twenty years. Rather, at the time of the murders

he was living at a different address and that during that period of time he

also spent significant amounts of time in prison. (R:6).

Upon this showing, the Racine County Circuit Court issued a search

warrant for Multaler’s home in Milwaukee. The stated purpose was to

search for items of personal property belonging to the murder victims.

Police executed the search warrant and did not find any evidence

connecting Multaler to the stranglings. They did, however, find two

computer diskettes which contained a number of images of child

pornography.

10

ARGUMENT

I.

THE AFFIDAVIT SUBMITTED IN SUPPORT OF THE

APPLICATION FOR A WARRANT TO SEARCH MULTALER’S

HOME ON ARROW STREET WAS INSUFFICIENT TO ESTABLISH

PROBABLE CAUSE AND INCLUDED FALSE INFORMATION

WHICH WAS MATERIAL TO THE TRIAL COURT’S PROBABLE

CAUSE DETERMINATION.

Probable cause to search Multaler’s home in this case depends upon a

rather lengthy syllogism: (1) That “serial killers” tend to retain mementos

taken from their victims; (2) That serial killers tend to retain such

mementos indefinitely even after they are no longer killing victims; (3)

That James Multaler is a serial killer; (4) That James Multaler killed the

victims alleged in the affidavit; and, therefore, mementos from the victims

are likely to still be in Multaler’s home twenty-four years after the last

victims was killed despite the fact that Multaler had been in prison for a

lengthy period of time after the murders.

The affidavit filed in support of the search warrant application fails to

establish probable cause on three important points: (1) That Hanrahan was

an expert in detecting serial killers such that the issuing judge was

permitted to accept Hanrahan’s opinions concerning the propensities of

serial killers; (2) Even if Hanrahan’s opinions are sufficient, there was no

probable cause to believe that Multaler was the person who strangled the

four victims; much less that he is a serial killer (however that term is

defined) who is likely to remove items of personal property from a victim

and save them); and, (3) That, under the circumstances of this case,

Multaler is likely to have maintained possession of any such items for

nearly twenty-four years. As will be set forth in more detail below, in

order to establish that Multaler ever had possession of the personal items

there must be probable cause to believe that he is the killer and there is not.

Moreover, even if he did at some point have possession of the items, the

information in the affidavit is stale- that is, there is no reason to believe that

the items would still be located in Multaler’s home.

On review of a denial of a suppression motion, (the appellate court) will

uphold the trial court's findings of historical fact unless they are against

the great weight and clear preponderance of the evidence. Jackson, 147

Wis.2d at 829, 434 N.W.2d at 388.

This is the equivalent of the

"clearly erroneous" test set forth in sec. 805.17(2), Stats. Noll v.

Dimiceli's, Inc., 115 Wis.2d 641, 643, 340 N.W.2d 575, 577

(Ct.App.1983).

Whether those facts satisfy the constitutional

requirement of reasonableness presents a question of law, and therefore

11

we are not bound by the trial court's decisions on that issue. (citation

omitted).

State v. Anderson, 149 Wis.2d 663, 439 N.W.2d 840, 847 (Wis.App.

1989).

Here, no findings of fact were made by the trial court. Rather, the trial

court merely applied the facts alleged in the affidavit to the constitutional

standard of reasonableness under the Fourth Amendment. Therefore, this

court reviews the matter as a question of law and the court need pay no

deference to the determination of the trial court.

Probable cause must exist, at the time the warrant is issued, to believe

that the objects sought would be found at the defendant’s residence. Rice

v. Wolff, 513 F.2d 1280, 1285 (8th Cir. 1975), rev'd on other grounds sub

nom. Stone v. Powell, 428 U.S. 465 (1976); United States v. Damitz,

495 F.2d 50, 54 (9th Cir. 1974): United States v. Boyd, 422 F.2d 791, 792

(6th Cir. 1970).

It is not required, however, that the judge “determine whether in fact the

items to be searched for are located at the premises to be searched, but only

whether there is reasonable ground to believe that they are there.” Damitz,

495 F.2d at 55 (emphasis in original) (footnote omitted). Accord, State v.

Benoit, 83 Wis.2d 389, 399-400, 265 N.W.2d 298, 303 (1978). The

judge is permitted to make the usual inferences reasonable persons would

draw from the facts presented. Bast v. State, 87 Wis.2d 689, 692-93, 275

N.W.2d 682, 684 (1979).

However, probable cause ceases to exist when it is no longer reasonable

to presume that items, once located on the premises, are still there. United

States v. Brinklow, 560 F.2d 1003, 1005 (10th Cir. 1977), cert den. 434

U.S. 1047 (1978).

The analysis to be employed in determining whether facts are too stale

to give rise to probable cause was discussed in United States v. Weinrich,

586 F.2d 481, 49u (5th Cir. 1978), cert den. 441 U.S. 927 (1979). There,

the court explained:

The function of a staleness test in the search warrant context is not to

create an arbitrary time limitation within which discovered facts must be

presented to a magistrate. Rather, the assay focuses on one relevant part

of the determination that reasonable probable cause exists to warrant the

issuance of an order to perform a wiretap or make a search. Out-of-date

information as to a single transaction could be seen to describe no more

12

than an isolated event in the past. Such an affidavit would not create

probable cause to believe that similar or other improper conduct is

continuing to occur.

On the other hand, information which

demonstrates a chain of related events covering a broad span of time

continuing to the current period may furnish a most reliable indicia of

present activity, thereby clearly demonstrating that probable cause exists

for the order to intrude.

Staleness is therefore an issue which must be determined on the

particular facts of the case. The factors which must be considered are: (1)

the lapse of time involved; (2) the nature of the criminal activity; and (3)

the kind of property to be searched for and seized. United States v.

Steeves, 525 F.2d 33, 38 (8th Cir. 1975).

The interplay of these factors determines whether the recitations in the

affidavit are too stale to support a finding of probable cause. Thus, while

the element of time is “crucial,” Brinklow, 560 F.2d at 1005, “a mechanical

count of the days is of little assistance in this determination.” United

States v. Hyde, 574 F.2d 856, 865 (5th Cir. 1978). It is reasonable to

suppose, for example, that business records will be maintained for an

extensive period of time, and a three month delay in obtaining warrants to

seize such records has been held not to preclude a determination that the

records will probably be found if a search is conducted. Andreson v.

Maryland, 427 U.S. 463, 478 n. 9 (1976). Similarly, if an affidavit recites

“a mere isolated violation” it can be reasonably presumed that 'probable

cause quickly dwindles with the passage of time. If the affidavit sets forth

activity indicating “protracted or continuous conduct,” however, the

passage of time becomes less significant. Bastida v. Henderson, 487 F.2d

860, 864 (5th Cir. 1973). The test to be used to determine whether the

relationship of the factors is such that the information in the affidavit is too

stale to support a finding of probable cause “is one of common sense.”

Brinklow, 560 F.2d at 1006.

A. There are no facts set forth in the affidavit to support Hanrahan’s

“mementos” opinion.

The lynchpin in the probable cause syllogism is Hanrahan’s opinion that

serial killers tend to maintain mementos from their victims.

Here, that

lynchpin is faulty because there is no factual basis stated in the affidavit to

support the opinion.

As will be set forth in more detail below, it is undisputed that a court

may consider the opinions and inferences of the affiant in an application for

a search warrant; however, it is imperative that a factual basis be

13

established for the the affiant’s opinion- otherwise, the court is left with no

means of evaluating the opinion. When that happens the probable cause

determination is made not by an impartial magistrate but, rather, by a police

officer engaged in the competitive enterprise of ferreting out crime. Here,

Hanrahan has no personal experience in investigating serial killers.

Rather, everything he knows was told to him by some other person (i.e.

books, speakers at symposia, etc).

Nowhere does the affidavit recite

that any of the experts in the area of serial killers hold the opinion that

serial killers keep mementos. Rather, this “mementos opinion” is

apparently Hanrahan’s own opinion and there is no factual basis in the

affidavit for him to hold such an opinion. As such, the court must reject it.

It is a rule of long standing that,

The magistrate may not accept without question the suspicions or

conclusions of a complainant but, on the contrary, must determine the

existence of probable cause after being apprised of the relevant facts.

In performing this function, the magistrate or court commissioner serves

as a judicial officer and must act in a neutral and detached manner. He

must receive an adequate answer to this hypothetical question: 'What

makes you think that the defendant committed the offense charged?'

Jaben v. United States (1965), 381 U.S. 214, 224, 85 S.Ct. 1365, 1371,

14 L.Ed.2d 345. (emphasis provided).

State ex rel. White v. Simpson, 28 Wis.2d 590, 137 N.W.2d 391, 393 (Wis.

1965).

It is not disputed that the experience and special knowledge of police

officers who are applying for a search warrant are among the facts which

may be considered. Steele v. United States, 267 U.S. 498 (1925). “There

would be little merit in securing able, trained men to guard the public peace

if they could not conclude from what they saw, heard and smelled, that the

law was being violated. State v. Harris, 256 Wis. 93, 39 N.W.2d 912, 916

(Wis. 1949). Additionally, some federal courts have recognized that

probable cause to search may be based upon who the subject of the warrant

is (i.e. drugs are likely to be kept where drug dealers live). United States v.

Singleton, 125 F.3d 1097, 1102 (7th Cir.1997).

Nonetheless, the facts upon which the applicant for a search warrant

bases his opinion must appear in the record, Harris, supra. Otherwise,

"[T]he inferences from the facts which lead to the complaint will be drawn

not ‘by a neutral and detached magistrate,’ as the Constitution requires, but

instead, by a police officer ‘engaged in the often competitive enterprise of

ferreting out crime’.” Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U.S. 108, 115 (1964).

14

Here, the Court of Appeals specifically relied upon Hanrahan’s

“training and research.” State v. Multaler, 2001 WL 641802*16 (Wis.App.

2001); Appendix A. This “training and research” is set forth in paragraphs

sixty through sixty-seven of Hanrahan’s affidavit (Appendix B) and

amounts to him having attended several symposia on the topic of serial

killers and having read a number of books on the topic. Significantly, the

affidavit does not allege that Hanrahan has any personal experience in

investigating serial killers.

The sort of “propensity” opinion testimony at issue here presents a

special challenge in a probable cause context.

The law requires that the

issuing judge be presented with the underlying facts upon which a police

“propensity” opinion is based in order that the judge may draw his own

conclusion- this is so that the court is not forced to blindly accept the

opinion of the officer.

It is very significant that Hanrahan’s opinion in this case is not based

upon personal experience but, rather, on what he has read and what he has

been told- in other words, it is based purely upon hearsay. Hearsay may be

used to support probable cause but there must be some showing in the

affidavit that the hearsay is reliable.

Here, the affidavit lists in detail the sources from which Hanrahan

received information, it does not set forth any of the information provided

by each source. Rather, the affidavit merely recites the names of the books

and the names of the symposia to which Hanrahan was exposed and then, in

paragraph 68, Hanrahan states, “[T]hat based on his training and research,

serial homicide offenders often take clothing, jewelry and other property . .

.” The opinion, apparently, is Hanrahan’s own and is not something which

was told to him by the persons with experience.

The affidavit does not state, for example, that Robert D. Keppel, Ph.D.

(mentioned in paragraph 63) discovered that Ted Bundy kept mementos

from his victims, or that the Green River Murderer kept mementos from

each of his 49 victims.

The “mementos” opinion, according to the affidavit, is Hanrahan’s own

opinion and it is not possible to determine how he arrived at it.

One

thing is for sure, the opinion was not arrived at through Hanrahan’s own

experience.

In other words, just because Hanrahan has read a few books on serial

15

killers does not mean that is permitted to offer any opinion at all concerning

serial killers and that the trial court is obligated to accept that opinion

without question. On the contrary, the trial court is required by law to

question the basis for any opinion offered in an affidavit in support of a

search warrant.

Here, it is impossible to know whether the “mementos” opinion is based

upon what some other investigator specifically told Hanrahan based upon

an actual investigation or whether this is just some inference drawn by

Hanrahan personally from what he has read. There simply is no way to

judge the accuracy of the opinion and where there is no factual basis upon

which to judge the accuracy of the opinion the court must reject it.

B. There is no probable cause to believe that Multaler committed the

murders and, in the absence of such probable cause, there cannot be

probable cause to believe that his home contains evidence of the crimes.

Even if one accepts the opinion that serial killers tend to maintain

mementos of their victims, in this case there must also be probable cause to

believe that Multaler killed the specific victims alleged and that he is a

serial killer.

As mentioned above, in order to issue a search warrant there must be

probable cause to believe that the defendant’s home contains evidence of a

crime.

Under the facts of this case, then, it necessarily follows that in

order for there to be probable cause to believe that Multaler’s home

contains the personal items of the murder victims there must be probable

cause to believe both that Multaler is the murderer and, further, that he is a

“serial killer”. That is, the only way Multaler could have possession of the

personal items of the victims at all is if he is the one who killed them; and,

further, the only way the items are likely to still be in Multaler’s home is if

he is a “serial killer” with the propensity to retain personal items of the

victims. Therefore, the affidavit must establish probable cause to believe

both that Multaler is the murderer and that he is a “serial killer.”

On this point, the Court of Appeals wrote:

First, the facts in Investigator Hanrahan's affidavit easily defeat

Multaler's challenge to the circuit court's probable cause determination

that he had killed the four females. Without revisiting all the details

here, and having summarized the most salient portions of the affidavit in

the factual background of this opinion, we merely observe that the

affidavit carefully and comprehensively connected Multaler to the

apparent murders. It related evidence, both direct and circumstantial,

16

that provided the circuit court with a substantial basis for finding

probable cause to believe that Multaler had committed the apparent

murders.

State v. Multaler, 2001 WL 641802 *6; (Appendix A).

Contrary to the opinion of the Court of Appeals, though, it is necessary

to revisit all of the details. The details of this case do not “carefully and

comprehensively” connect Multaler to the crimes.

In , State v. Secrist, 224 Wis.2d 201, 589 N.W.2d 387, 391 (Wis. 1999)

the Supreme Court of Wisconsin explained:

It may be helpful at the beginning of our analysis to note the distinction

between probable cause to search and probable cause to arrest. (FN6)

Generally, the same quantum of evidence is required whether one is

concerned with probable cause to search or probable cause to arrest.

State v. Kiper, 193 Wis.2d 69, 82, 532 N.W.2d 698 (1995) (citing 1

LaFave, Search and Seizure: A Treatise on the Fourth Amendment, §

3.1(b), at 544 (2d ed.1987)). However, while the two determinations are

measured by similar objective standards, the two determinations require

different inquiries. Under an analysis of probable cause to search, the

relevant inquiry is whether evidence of a crime will be found. See 2

LaFave, Search and Seizure, § 3.1(b), at 7-8 (3rd ed.1996). Under an

analysis of probable cause to arrest, the inquiry is whether the person to

be arrested has committed a crime. See id.

The affidavit goes into great length concerning suspicious

circumstances surrounding Multaler and the stranglings; however, there is

no basis to conclude, even to the level of probable cause for a search

warrant, that Multaler is the one who committed the crimes. Obviously,

then, there is no probable cause to believe that Multaler is a serial killer.

On this point, the salient details fall into one of four categories: (1)

Facts tending to establish Multaler’s unusual sexual proclivities; (2) Facts

tending to establish Multaler’s interest in the cases; (3) Facts establishing

opportunity for Multaler to have committed the crimes; and (4) Facts

gleaned from books concerning the investigation of serial killers.

Concerning the first category, the unusual sexual proclivities, the

affidavit recites numerous facts tending to establish that Multaler

evidently had a habit of choking women with whom he was having sexual

intercourse (see, e.g. para. 43). In what is supposed to be privileged

communications, Multaler told doctors at the Central State Hospital that he

enjoys “playacting” with women concerning strangulation and that this

17

sexually arouses him. This information has almost no tendency to

establish that Multaler is the killer.

Firstly, the affidavit alleges no cause of death for Wendy Gail Brown

nor for Sherry Lynn Moriarity. The cause of death for Cynthia

Franckowiak and Susan Wicinski was ligature strangulation. There are no

facts alleged from which it may be inferred that the deaths were in any way

sexually motivated. The closest the affidavit comes is to allege that semen

was found in the vagina of Sherry Moriarity (para. 80) and that two of the

women had their shirts pulled up over their breasts. Thus, any unusual

sexually proclivities on the part of Multaler make it no more or less likely

that he is the killer.

More importantly, though, the affidavit consistently alleges that the

victims were strangled to death using a ligature of some sort. None of the

women who were interviewed for the affidavit stated that Multaler used any

sort of a ligature on them- much less did he strangle them to death. Rather,

according to the affidavit Multaler used his fingers on the necks of the

women (see para. 43, 42, 49, 30). Therefore, Multaler’s sexual proclivities

are inconsistent with the evidence of the cause of death of the victims.

The second category of facts in the affidavit is that Multaler may have

had an interest in the cases. It is alleged that he kept a scrap book of

newspaper clippings and that he may have inquired of a television station

concerning video footage.

An interest in the cases, even as part of the

“totality of the circumstances” lends nothing to the probable cause

determination as to whether Multaler is the killer.

Finally, the third category of facts, that Multaler may have had an

opportunity to kill the women is, basically, meaningless since thousands of

people in Milwaukee were also in the same general area of the murders.

The affidavit alleges that Multaler has frequented Racine County and that

is where the bodies were found (para. 45). It also alleges that Multaler

frequented places which were within blocks of where two of the bodies

were found (para. 50, 52).

Plainly, the fact that Multaler has been near

the areas where the bodies were found does nothing the establish that he is

the killer. That fact also applies to thousands of other people.

Even taking all of these facts together (the so-called “totality of the

circumstances”) and even taking into account the fourth category of facts in

the affidavit (the information about serial killers) it does nothing more than

make Multaler suspicious; and, as has been oft repeated, “Probable cause . .

. requires more than an officer's subjective good faith belief or mere

18

suspicion.” Leroux v. State, 58 Wis.2d 671, 207 N.W.2d 589, 596 (Wis.

1973).

If one is unable to conclude even to the level of probable cause that

Multaler is neither the murderer nor a “serial killer” then it is logically

impossible for there to be probable cause to believe that the personal items

of the victims would be located in Multaler’s home.

19

C. Even if probable cause did exist to believe that Multaler was the

murderer and a serial killer, the information in the affidavit was stalethat is, no inference may be drawn that the items would still be located in

Multaler’s home.

Even if this court were to assume, for the sake of discussion, that

Multaler is the “South Side Killer” as insinuated in the affidavit, there still

was no probable cause to believe the items would still be located in

Multaler’s home some twenty-three years later. That is, the information in

the affidavit is stale.

The cases point out that the passage of time is critical but that it cannot

be measured purely in the number of days, weeks, or years which have

passed.

The passage of time must be measured against the nature of the

criminal activity involved and the sort of item which the police are

attempting to find in the defendant’s home. Significantly, the courts have

mentioned that where there is continuing or protracted criminal activity the

passage of time is less important.

Here, Paragraph 74 of the affidavit acknowledges, “[A]fter Multaler’s

arrest for the kidnapping of Debra Whitaker, these strangulations stopped.”

Multaler was arrested for the Whitaker case in 1975. Although he was

imprisoned for a period time after that, he was also free for a significant

period of time and still there were no additional stranglings. As such, there

is no basis to conclude that the criminal behavior alleged in the affidavit

was ongoing or protracted.

Thus, the immense passage of time, combined with the fact that even if

Multaler was a serial killer at some point in his life, he has controlled his

impulses for a lengthy period of time continuing up to the present time,

makes it virtually impossible that he would still have possession of the

items that the state is looking for.

Firstly, retaining possession of the victims’ items, according to the

affidavit, is a propensity unique to a serial killer. Under the facts alleged

in the affidavit there is no reason to believe that Multaler engaged in this

sort of behavior for many years. Thus, there is no reason to believe that he

continued to need possession of the items.

More importantly, though, is the fact that Multaler was imprisoned for

a period time after 1975. Thus, in order to maintain possession of these

items it would have required the cooperation of Multaler’s friends and

family. Under the facts of the affidavit, Multaler’s wife (at the time she

20

was a girlfriend), Patricia, was interviewed by police. Patricia made

numerous statements to police which portrayed Multaler in a very negative

light (i.e. choking, etc., see para. 43) but, significantly, she never mentioned

to police finding any items of women’s property in her home. It simply is

not reasonable to infer, given the information provided by Patricia to the

police, that she would hide such a fact in order to protect Multaler.

Also, the appellate courts have instructed that the “nature of the items”

must also be considered. For example, business records might be expected

to be retained longer than other items. Here, the items listed are things

such as B-B sized ear rings, perfumes bottles, and the like. The odds of

such things being retained by any person for any reason over the course of

twenty years are exceedingly remote.

Add to this the fact that Multaler was also in prison for nearly ten of the

twenty-four years and it makes it virtually impossible that those sorts of

small personal items could still be found in Multaler’s home in 1998.

Therefore, the court should find that the affidavit filed in support of the

application for the warrant to search Multaler’s home did not establish

probable cause to believe that the items of personal property belonging to

the victims would be located there. As such, all evidence seized by police

during the search of Multaler’s home should have been suppressed.

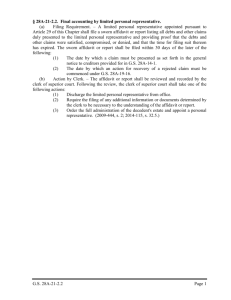

II. THE INFORMATION WAS MULTIPLICITOUS.

It was not the legislature’s intent in creating sec. 948.12, STATS.,

(possession of child pornography) that the allowable unit of prosecution be

for each image possessed; rather, like other contraband statutes, in order to

charge a separate count there must be a significant difference in time or a

significant difference in the nature of the conduct. Thus, since Multaler

was found in possession of diskettes, without any significant difference in

time or in the nature of the conduct, the allowable unit of prosecution is

one.

A. Multaler’s multiplicity claim was not waived by his Alford

plea.

Normally, a guilty or no contest plea waives all non-jurisdictional

defects.

However, because Multaler’s multiplicity claim may be

determined by the matters of record this court must consider it.

21

The fact that Multaler’s double jeopardy claim was not waived by

his no contest pleas is apparent from a reading of State v. Hubbard, 206

Wis.2d 651, 558 N.W.2d 126, 129 (Wis.App. 1996) where the court

explained,

In Broce, the defendants claimed double jeopardy as part of a

collateral attack on allegedly multiplicitous charges, and a determination

of the double jeopardy [206 Wis.2d 656] issue would have required the

court to go beyond the record. Id. at 574-76, 109 S.Ct. at 764-66.

Here, Hubbard's claim is on direct appeal from convictions where the

potential double jeopardy violation is facially ascertainable on the record

without supplementation. We conclude that Hubbard's no contest pleas

establish his "factual guilt" on the six counts but do not bar his claim

that, judged on their face, the charges violate double jeopardy. See

Menna v. New York, 423 U.S. 61, 62 n. 2, 96 S.Ct. 241, 242 n. 2, 46

L.Ed.2d 195 (1975). (emphasis provided)

Here, the facts of what Multaler pleaded guilty to are

well-established- the police found two computer diskettes in his house

which contained numerous individual digital images of child pornography.

In his postconviction motion Multaler merely argued that his numerous

convictions for child pornography violated the double jeopardy clause

because the plain language of the statute involved makes it clear that the

legislature intended the unit of prosecution to be for each separate medium

containing illegal images- not for each separate image.

There is absolutely no need to go beyond the record in order to decide

the motion. Rather, Multaler encourages the court to primarily examine

the language of the statute.

Before the Court of Appeals, the State argued that waiver of

multiplicity claims based upon the charges violating the will of the

legislature should be treated differently than waiver of multiplicity claims

based upon a double jeopardy violation.

There is no reason in logic to distinguish between the two forms of

multiplicity challenges. A guilty plea waives all non-jurisdictional defects

including claims of constitutional error. State v. Princess Cinema of

Milwaukee, Inc., 96 Wis.2d 646, 651, 292 N.W.2d 807, 810 (1980).

However, the Hubbard decision carved an exception to the waiver rule for

multiplicity challenges not because some claims are constitutional in nature

but, rather, because the claims may be determined on the record without

supplementation. 558 N.W.2d at 128, 129.

Secondly, it would be a monumental waste of judicial resources to

22

require a defendant to go to trial in order to preserve his appellate rights

where his only claim is that the charges are multiplicitous because they

violate the will of the legislature.

Moreover, there are circumstances

where, as in this case, such a requirement might violate due process. As

part of the plea agreement the state agreed to dismiss numerous counts.

It would certainly seem unfair to force Multaler to choose between taking

advantage of the plea agreement or giving up his appellate rights on the

issue of multiplicity.

B. The charges are multiplicitous

Charges are multiplicitous if they are identical in law and in fact.

See State v. Davis, 171 Wis.2d 711, 716, 492 N.W.2d 174, 176

(Ct.App.1992). Because Multaler was charged with multiple violations of

§ 948.12, STATS., those charges are the same in law. See Davis, 171

Wis.2d at 716, 492 N.W.2d at 176. However, whether they are the same in

fact depends upon whether one count requires proof of an additional fact

which the other does not. See id. Offenses are different in fact if they are

separated in time, are significantly different in nature, or if each involves a

separate volitional act. See id. at 717, 492 N.W.2d at 176. Separate

volitional acts occur when there is sufficient time between the acts for the

defendant to reflect upon his or her actions and recommit himself or herself

to the criminal activity. See id. at 717-18, 492 N.W.2d at 176.

Significantly, though, where a defendant is charged with multiple

offenses which are the same in law but different in fact may still be

multiplicitous if the legislature intended that only a single count should be

charged. See State v. Carol M.D., 198 Wis.2d 162, 173, 542 N.W.2d 476,

480 (Ct.App.1995). Where the statute in question does not specifically

state the allowable unit of prosecution the court must, “[C]onsider four

factors to ascertain legislative intent: (1) the statutory language; (2) the

legislative history and context; (3) the nature of the proscribed conduct;

and (4) the appropriateness of multiple punishment. State v. Warren, 229

Wis.2d 172, 599 N.W.2d 431,438 (Wis.App. 1999).

B. The statutory language makes plain that it is the possession of

the medium containing the pornographic images which is the allowable

unit of prosecution.

The relevant language of sec. 948.12, STATS., is as follows:

“Whoever possesses any undeveloped film, photographic negative,

photograph, motion picture, videotape or other pictorial reproduction or

audio recording of a child engaged in sexually explicit conduct . . . . .” is

23

guilty.

Two points are very significant in determining the allowable unit of

prosecution under sec. 948.12, STATS.

Firstly, the legislature chose

to itemize each medium on which a pornographic might be contained (i.e.

film, photographic negative, etc.) Thus, it is plainly the possession of the

medium containing the images which is outlawed. More importantly,

though, is the fact that if the legislature intended that the allowable unit of

prosecution to be for each image possessed, they would certainly have said

so. In that case the statute would read, “Whoever possesses an image,. in

whatever form, of a child engaged sexually explicit conduct is guilty . . . “

The Court of Appeals rejected Multaler’s argument in this regard

focusing upon the “pictoral reproduction” phrase of the statute and also

upon the legislative history. Moreover, the Court of Appeals relied upon

its own comment in another context that, “[W]e are satisfied that the focus

of the inquiry under the statute is the content of the photograph and how it

was produced, not the particular location or manner in which it is ultimately

stored or kept by the person possessing it.” State v. A.H., 211 Wis.2d

561, 566 N.W.2d 858, 860 (Wis.App. 1997)

The Wisconsin Supreme Court, though, has not made a similar

observation nor should such an observation be made in this case.

The words of a statute must be given their plain meaning and the

appellate court may refer to extrinsic aids only when the statute is vague.

Here, the statute is not vague. Furthermore, under the principle expressio

unius est exclusio alterius since the statute does not read, “Whoever possess

an image, in whatever form, of a child engaged in sexually explicit conduct

. . .” that interpretation is excluded.

It is so well known that it is practically unnecessary to repeat it that:

The purpose of statutory interpretation is to discern the intent of the

legislature. See State ex rel. Jacobus v. State, 208 Wis.2d 39, 47-48,

559 N.W.2d 900 (1997). To discern that intent, we first consider the

language of the statute. If the language of the statute clearly and

unambiguously sets forth the legislative intent, we apply that intent to the

case at hand and do not look beyond the legislative language to ascertain

its meaning. See Kelley Co., Inc. v. Marquardt, 172 Wis.2d 234, 247,

493 N.W.2d 68 (1992); see also UFE Inc. v. LIRC, 201 Wis.2d 274,

281-82, 548 N.W.2d 57 (1996).

Lincoln Sav. Bank, S.A. v. Wisconsin Dept. of Revenue, 215 Wis.2d 430,

24

573 N.W.2d 522, 527 (Wis. 1998).

The reasoning of the Court of Appeals makes it apparent that the

appellate court understood “reproduction” to be synonymous with image.

This is simply not the case.

The definition of “reproduction” is:

re·pro·duc·tion [rpr dúkshn] (plural re·pro·duc·tions) noun

1. copy of object: a copy of something in an earlier style, especially a

painting or a piece of furniture

2. reproducing of something: the act or process of reproducing something

3. print, electronic, or photographic duplicate: a copy of something printed,

scanned, photographed, or produced by other means

4. RECORDING recording of sound: the recording of sound or the quality of

recorded sound4

The plain meaning of “reproduction” refers to the act or the process of

reproducing something or a copy of something printed, scanned,

photographed, or produced by other means.

If there were any doubt about the plain meaning, though, the context of

the statute makes it clear. The phrase “pictorial reproduction” comes at the

end of a list of media including photograph, moving picture, and so forth.

There is absolutely no doubt that under the plain meaning of the statute

it is the possession of the medium which contains a pornographic image

which is prohibited.

Just as clear is the fact that the legislature could have written the statute

to prohibit the possession of individual images but did not do so. That is,

instead of prohibiting the possession of images, in whatever form, the

legislature instead chose to list each of the various media on which images

might be stored. “[A] general rule of statutory construction, Expressio

unius est exclusio alterius (the expression of one thing is the exclusion of

another) . . . . provides that ‘. . . the express mention of one matter

excludes other similar matters not mentioned." Columbia County v.

Bylewski, 94 Wis.2d 153, 288 N.W.2d 129, 137 (1980).

Thus, the fact that the legislature specifically mentioned the various

forms of media containing pornographic images but did not simply prohibit

4

Encarta® World English Dictionary © & (P) 1999 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Developed for Microsoft by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

25

the possession of images in whatever form, is overwhelming evidence that

it was not the intent of the legislature to permit one count for each image.

It must be mentioned as a side note that the Court of Appeals’

description of the purpose of the statute (i.e. to prevent exploitation of

children) is entirely consistent with the plain meaning of the statute.

If the purpose of the statute is to prevent exploitation of children then

Multaler’s view of the plain meaning is perfectly consistent but the state’s

“interpretation” makes no sense. The children who are forced to engage in

sexually explicit behavior are no more or less exploited whether one

photograph of the act is taken or whether forty photographs are taken.

Likewise, the child is not subject to greater harm if one photograph is taken

but is printed fifty times. The damage is done. It is the sexual act which

harms the children, not the number of images recorded. Therefore, the

legislature chose to criminalize the recording of the acts regardless of the

medium used.

The state’s argument that the legislature intended to permit one count

for each image would make sense only if it was the legislature’s

determination that it is the images of child pornography, in and of

themselves, which are evil. According to the state, though, this is not the

case. Rather, the legislature sought to deter the exploitation of childrenthe legislature did so by prohibiting the recording of sexual acts by

children.

C. It is highly inappropriate to impose multiple punishments for

each separate image possessed.

In order to be consistent, if one defendant is charged with five counts

of possession of child pornography for possessing five pictures in a

magazine then a second defendant possessing a five minute pornographic

movie must be charged with 9000 counts of possession of child

pornography5 and would thereby be facing a maximum penalty of 180,000

years in prison for one five minute movie.

There is no distinction in logic or in fact between the individual

frames in a 35mm motion picture and the individual frames on a roll of

35mm photographic film. The only difference is that if the motion picture

film is loaded into a machine it will project an image which appears to

move.

5

At the standard rate of 30 frames per second a five minute movie would have 9000 separate images.

26

Likewise, there is no logical distinction between the frames on a roll

of motion picture film and individual “files” (images) on a floppy disk. In

fact, it is possible to store a two hour digital video in one large file on a

DVD disk.

Can any reasonable person really believe that it is fair and

appropriate to charge Multaler with twenty-eight counts because his two

floppy disks contained that number of “files” but a person who possessed a

two hour pornographic digital video on a DVD disk may only be charged

with one count because there was only one very large file?

Thus, it is not appropriate to impose multiple punishments for each

“image” of child pornography which a defendant possesses.

Rather, the

court may impose multiple punishments for possession of child

pornography only where it can prove that there is a significant difference in

time (i.e. the images were received by the defendant at different times) or

where there is a significant difference in the conduct (i.e. possessed a video

tape and a magazine).

For these reasons it is respectfully requested that the court strike

Multaler’s conviction on all counts except one and to resentence the

defendant accordingly.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully requested that the Supreme Court reverse the order

of the Court of Appeals affirming the trial court’s order denying

Multaler’s motion to suppress all evidence, vacate Multaler’s conviction on

each count, and to remand the matter for further proceedings consistent

with the court’s order.

In the alternative, it is requested that the Supreme Court declare that

the information filed against Multaler was multiplicitous and order that all

counts except one be dismissed.

Dated at Milwaukee, Wisconsin this ____ day of ____________, 2001.

LAW OFFICES OF JEFFREY W.

JENSEN

Attorneys for Appellant

27

By:______________________________

Jeffrey W. Jensen

State Bar No.

01012529

633 W. Wisconsin Ave.

Suite 1515

Milwaukee, WI 53203

(414) 224-9484

28