Thy Decay Thou Seek'st by Thy Desire

advertisement

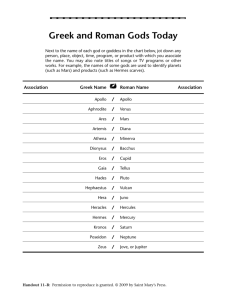

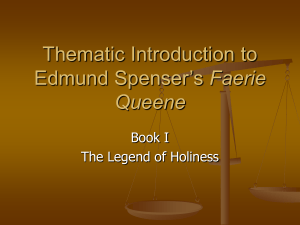

Thy Decay Thou Seek’st by Thy Desire The year is 1599. A middle-aged man, perhaps aware that he would soon die, looked back upon his life’s project, to become his nation’s epic poet, celebrating the culmination of the pagan and the Christian past in a Protestant empire led by the maiden queen, Elizabeth. What had become of that project? His masterpiece, The Faerie Queene, lay incomplete, its final stanza a reproach against slanderous tongues at court, their “venemous despite,” and, by implication, against the royal ear that believed them. The queen herself, never the maiden she made herself out to be, was enfeebled with age, and had not named an heir. The radical Protestant hopes for establishing a single true Church in the world, as the great enemy of that painted harlot in Rome, had long been shown as vain; and those Protestants in England who, like the poet, favored an aggressive foreign policy, or who sympathized most strongly with the Calvinist Dutch, were quickly dissociating themselves from the English church itself, and would one day come to dispense with both bishops and kings. Then there were troubling signs in the heavens. Not that the poet was superstitious. The great supernova of 1576 had done far more to alter the European view of the world than Copernicus’ heliocentrism – with its affinity with Neoplatonic thought – had done. For now, even with the crude optical devices then available, it had been proved that the bright object suddenly appearing in the sky lay far beyond the circuit of the moon, in the region where no change was supposed to occur. So the poet, Edmund Spenser, meditated upon the meaning of change, exerting all his mythopoeic powers to provide a fit end for his masterpiece and his career, writing the socalled Cantos of Mutability. The title page informs us that these were to be cantos six, seven, and eight (and I beg the reader to keep those numbers in mind) of a supposedly unfinished seventh book of The Faerie Queene, a book dedicated apparently to the virtue of Constancy. At first glance it appears that change will be the enemy of all fidelity and steadfastness. And indeed Spenser seems to have divined something of our nihilism – our call for change, change for its own sake, for we are bored with the nothing before us, and long for innovation, if only to distract us from the pointlessness of what is. The premise of the Cantos seems simple enough. A goddess named Mutability, one of the race of Titans overthrown by Jove, rises up in rebellion against him and all the other planetary-Olympian gods. Her argument is not only that she deserves to rule by virtue of her parentage, but that in fact she does rule. Mutability is the meaning, or the unmeaning, of all the world. At the least she is an inevitable datum of our lives, as certain as death. We do not only see her at work, undoing great empires; we feel her weight within ourselves: What man that sees the ever-whirling wheel Of Change, the which all mortal things doth sway, But that thereby doth find, and plainly feel How MUTABILITY in them doth play Her cruel sports, to many men’s decay? (The Faerie Queene, 7.6.1.1-5) We feel the whirling of that wheel, and we feel the “sway” of change, which seems not so much to govern us as to topple us over. Yet Spenser does not lapse into easy elegy, not here. Because his vision is Christian – or rather I should say because the Word, through whom all the changing things in the world were made, was made flesh and dwelt among us, in his own steadfast person subject to change – Mutability herself, a beautiful goddess and no monster, finds her proper place only within a providential design. The point is both metaphysical and existential. Change can only exist when there are things to change, or people who change; but such things and such people can only exist by virtue of constancy, which is something wholly other than immobility. It is the hidden meaning behind Spenser’s ambiguous statement of purpose: he will, he says, rehearse a story he heard from long ago, in the permanent records of Faery Land, “the better” to make Mutability’s ravages appear to us. That is, we will see more clearly how potent Mutability is, and yet we will see her in a better light, the comic light wherein Mutability is most herself and most beautiful, because she is subordinate to, and helps bring about the designs of, the One whose beauty is past change. She is, in both senses of the word, a locus of “sway.” But before I continue with Mutability, I should like to engage in my own orbital errancy and recall the great pagan alternatives to the Christian vision. It seems crucial to do so, because as the cultural memory of western man grows more feeble and distracted by creaturely pleasures, he is apt to lapse not into those alternatives, profoundly human as they are, but into a debased version of them. What are they? I believe they are two, and that each of them captures a portion of the truth – a portion which, as we will see, Spenser readily acknowledges. The first is that change is only apparent or superficial. Things revolve in cycles; empires rise and fall; summer fades and winter comes, then winter fades and summer comes again; people are born and die, and others are born in their place; the sun rises and sets, and rises again, and, to quote the half-pagan Preacher, nothing is new under the sun. The second is that change is essentially decay. Things fall apart, and that is all. The playwright Sophocles had seen his share of changes. As a lad, he led the youth of Athens in parade to celebrate their naval victory over the Persians at Salamis. As a young man he saw the revolution that replaced aristocratic rule with radical democracy. He was a close friend of Pericles. He watched as sophist and philosopher both turned education away from the traditional warrior-virtues espoused by Homer. He suspected the philosopher of pretending to know more about the moral law than he really knew, and the sophist, of pretending to know less. He saw Athens rise to empire, and watched her grow dangerously proud. Already an old man, he saw the Athenians declare war against Sparta and her allies, a war they could win only by exercising the patience that the statesman Pericles enjoined upon them. But the plague soon struck the city, and Pericles died. More than twenty years later, Athens would be defeated at last, and Sophocles would die at the age of ninety-three, longing for a return to the Athens he once knew. For, if change is no more than the cycle of rising and falling, then there is always the hope for a return; the fulfillment of nostalgia, that bittersweet longing for home, that most human form of despair. So in his final play, Oedipus at Colonus, produced in Athens after his death, Sophocles imagines not the glorious Acropolis, with its cash reserves extorted from Athenian allies, nor Athenian might at sea, but his simple native village of Colonus, outside the walls of the city. So the Colonian chorus sings of that beauty, which all those in Sophocles’ audience would understand had been ravaged by the Spartan infantry: Here, chosen crown of goddesses the fair Narcissus blooms, bathing his lustrous hair In dews of morning; golden crocus gleams Along Cephisus’ slow meandering streams, Whose fountains never fail; day after day His limpid waters wander on their way To fill with ripeness of abundant birth The swelling bosom of our buxom earth. (92) To bring him as close to the Christian Spenser as it is possible for the pagan to be, Sophocles sees that one can return to that idyllic Colonus only by returning to the unchanging virtues of justice and mercy that once characterized Athens. In the play, Theseus, the exemplar of Athens’ mythic past, grants protection to the old and blind Oedipus, against the Thebans who once cast him out as unclean, and who now wish, opportunistically, to drag him back to their city, as they have heard an oracle foretell that the land where Oedipus dies will be blessed. It is a battle of the Athens of old, symbolized by Theseus and the Colonian villagers, who are devoted to what we would call the natural law, and to the old customs of their homeland, against the new, democratic Athens, symbolized by Thebes, wherein virtue is only a word, for what the city calls right, is right, and all bow before the idol of utility. At its best, then, this pagan vision of cyclical change is anchored in what does not change. If it does not provide hope for the kingdom of God, or hope that the pilgrimage of time is going anywhere, it does at least hold out the possibility that what was good and noble in the past is not forever lost. That hope flickers throughout Greek poetry. Pindar cannot sing of the victory of a boy in the footraces of Olympia without commemorating the virtue of his father and his uncles, and the ancient strength of his homeland. Odysseus, that liar extraordinaire, wins our sympathy only insofar as we can feel his alge, his pain, for the noston or turning back, impossible for his fellow sailors who lack his self-control and succumb to the present needs of their bellies. When we first meet the man, he is sitting on the beach of Calypso’s island, looking out to sea, and longing for home. It is a deeply human and pious longing, that the past should not simply be past, and that the people we once knew and loved be not simply dissolved in the mists of change. But the second vision of change, that of random alteration and decay, would declare such a longing doomed to frustration. It too denies the pilgrimage of time, except perhaps insofar as time brings forth technological novelty. Here we might turn to the Epicurean poet Lucretius and his vision of social change. It is disturbingly modern. A long time ago, says Lucretius, men lived like the beasts of the field. They slept in caves, huddling from the cold. They foraged and hunted, they lapped at the mountain springs. They won their women by brute strength, or by giving them fine gifts, like really choice pears. Gradually they learned how to use fire to cook food and to forge tools, including instruments of war. They developed the social contract: tribes would agree not to hurt one another, and to spare the women and children. They invented writing, and attained, without divine inspiration, to the pinnacle of art. At the same time, they lost their ancient strength of limb. They also lost their simple delights and their natural piety. Lucretius imagines what it was like when, having been “taught” by the wind whistling through hollow reeds, men invented music: Then little by little they learned the sweet complaints That the pipe pours forth at the fingering-pulse of the players, Heard in the trackless forests, the shepherds’ dells, Places of sunlit solitude and peace. (5.1381-84) Such people enjoyed true pleasure, he says, despite the rusticity of their songs. But technological change sweeps everything aside, by the vain pleasure of novelty, compounded with the violence necessary to procure the novelties: So acorns came to be hated; so the strewn beds Of mounded grass and foliage were abandoned; And clothing made from pelts fell into contempt, Whose discovery, I’ll bet, aroused such envy That the first wearer was assassinated, And, worse, the killers in their rivalry ripped The blood-soaked hide to bits – so no one got it! In those days it was pelts, now gold and purple March men to war, to weary human life. (1411-19) Technological improvement did not coincide with moral improvement. If anything, Lucretius seems to have believed that moral degeneracy had set in. Says he, comparing the men of old to the men of his day: Poison they often took unwittingly; We are more skillful now – we give it to others. (1006-1007) The world we know is falling apart. The best one can do is to set one’s mind on the modest yet temporary pleasures of friendship. And that friendship itself is not defined as the union of virtuous souls in seeking the good that transcends our lives. It is not the fellowship of one man the pilgrim with another, their eyes set upon the distant City of Peace. It is rather a complacent amiability; we are friends, simply, because we enjoy one another’s company, as we eat and drink by the riverside, and talk a little philosophy. The yawning nihilism that underlies this vision becomes clear when Lucretius lashes out against people who mourn that they must die. “Get your sobs out of here, scoundrel,” cries his personified Nature of Things, “and quit your whining!” (3.952). For the same nature that causes the fields to bloom with grain and cities to bloom with children brings decay and death. As the time before we were born is nothing to us, so will be the time after we die. If there is any return, it is to meaninglessness: Survive this generation and the next – Nevertheless eternal death awaits, Nor will the man who died with the sun today Be nonexistent for less time than he Who fell last month – or centuries ago. (3.1087-91) I wish to argue that the confusion of our post-Christian world is evident in a residual trust, based not in faith but in superstition, that we are proceeding towards a kingdom of peace and plenty, without the humble awareness, which even Lucretius possessed, that we cannot provide that world of ourselves. So we flail about from a debased Sophocles to a debased Lucretius. Sometimes we lapse into a superficial primitivism, trusting that we will be saved by the magic color green, without however actually desiring to return to a vine-clad Colonus, to tend the grape and the fig, and live in honest and steadfast poverty. More typically, and with less real sense of the needs of human beings who dwell in time, we hope in change for change’s sake, with technology as the instrument for providing us with sufficient comforts to stay us against the awareness that for all our motion we are not going anywhere, that we are driven along in the ceaseless bustle of sloth, and that death is approaching anyway, the “eternal death” that Lucretius at least had the courage to confront. But perhaps our confusion is not so new, either. Spenser has, I believe, dramatized it in the ambiguous figure of Mutability. When we are first made aware of her existence, she is merely a rebel, a destroyer, a universal Adam who hopes to rise by his own power and who thereby destroys the dynamic yet steadfast happiness that should have been his forever: For, she the face of earthly things so changed, That all which Nature had established first In good estate, and in meet order ranged, She did pervert, and all their statutes burst: And all this world’s fine frame (which none yet durst Of Gods or men to alter or misguide) She altered quite, and made them all accurst That God had blessed, and did at first provide In that still happy state for ever to abide. (6.5.1-9) So Mutability begins her campaign straightforwardly enough, rising up against the Olympian gods who have their seats in the heavens, wishing to take their thrones by sheer might – to enforce upon them the change she represents. Thus she attempts to thrust the moon goddess Cynthia from her throne, regardless of the chaste goddess’s indignant refusal: Yet nathemore the Giantess forbare But boldly pressing on, raught forth her hand To pluck her down perforce from off her chair. (13.1-3) This upstart, apparently an embodiment of wilful violence, sends the comical old Olympians scurrying – what shall they do now? They meet in assembly before their ruler, Jove; and it should be noted that if Mutability stands for undirected change, mere innovation, forgetfulness of the claims of the past, then it is almost a jest that she should want to sit upon any throne at all, since in her own being she would destroy the possibility of assembly and the reliability of law. Yet we are in for a surprise – one whose nuances critics of Spenser have yet to understand, as they reject the cosmological comedy in which the poet believed. They have taken insufficient note of man’s existential state, as the one who is on the way, as Josef Pieper puts it – man whose hope is not in alteration, but in that final moment of allchanging arrival. For Mutability’s guilt is attenuated by the plain fact that she does not really understand what she is about. She is neither a metaphysician nor a deep meditator upon things human, but rather an ambitious woman seeking recognition of her rights, whatever those may be. If she paused to think of what man is, she might divine the hope that walks by change, to what lies beyond change. If she had been a metaphysician, she might have asked herself by what unchanging principle change has a right to rule; or by what unchanging standard of excellence change is beautiful. For beautiful she is; as she stands before the throne of Jove, pleading her descent from the old Titans, we are granted our first vision of the person of the goddess whom we had supposed to be no more than diabolical: Whilst thus she spake, the Gods that gave good ear To her bold words, and marked well her grace, Being of stature tall as any there Of all the Gods, and beautiful of face As any of the Goddesses in place, Stood all astonied. (28.1-6) Jove, that everlasting roue, himself looks upon her with something like the beginnings of infatuation. He is about to cast his thunderbolt at her, but beauty stays his hand, for, as Spenser says, “such sway doth beauty even in Heaven bear” (31.4). We begin to suspect that Mutability may not simply be, for Spenser, an emblem of random or meaningless change; for beauty, especially a beauty that governs or bears “sway,” presupposes order, and order presupposes an end for which the order is ordained. Jove does not destroy her – and Spenser leaves it unclear whether he could destroy her if he wanted to. Instead he pleads the feeble conservatism of the fait accompli: we rule, he says, because we conquered, and also “by eternal doom of Fate’s decree” (33.6), a claim which flickers unsteadily between the fatalism of Hesiod and the providentialism of Augustine. What that planetary chieftain means by it, we are not told, for Mutability parries the argument by making a fatal move. She impeaches Jove’s capacity to judge a case wherein he is a party. She appeals above the head of Jove (we had not been entirely aware that there was any being above Jove) to the “Father of Gods and men by equal might,” transferring that typically Jovian epithet to a mysterious “God of Nature” (33.6). Jove “did inly grudge” (8) to hear that name, but, preserving the order of a court of law, has his scribe Phoebus Apollo enter her appeal. Who is that God of Nature? Spenser leaves us in some suspense, revealing the identity, if he reveals it at all, only in the next canto. In the meantime he takes up an odd suggestion that Jove has made, to wit, that Mutability has been moved by intellectual presumption, “to see that mortal eyes have never seen” (32.3) And again Spenser attempts to teach us by means of subtly comic ambiguity. We are in fact the sorts of beings who are created precisely to see what mortal eyes have never seen, and to hear what mortal ears have never heard, and to know what it has not entered the mind of mortal man to conceive: namely, what God has provided, as Saint Paul says, for those who love him. We are made for that time-and-dust-transcending gift. But instead we wish to see it by means of mortal eyes; we want our eyes to be opened by the fruit within our reach, so that we might be as gods. We want to attain, by our own power, that secret knowledge that will set us above rule. The evil change we seek is not the change from the human to the divine, simply, but that same change by means of disloyalty and error. The virtue of constancy is not opposed to change as such, but to fickleness, which is change as its own wilful principle of action. In a sense, to try to attain the divine on our terms, to try to build up our own City of Peace, is to be too fainthearted and fickle to undertake the pilgrimage. We end up fixed in the mire of pointless change. It is the old sin, indeed the primal sin, and yet Spenser has anticipated its modern form. There is an uncanny connection, in our day, between desiring change for change’s sake, and trusting that we will be saved by the next scientific discovery or by the next massive social rearrangement, or by the latter in the service of the former. We are “progressing,” while acknowledging no transcendent Being or transcendent Good towards which we progress, nor even a decent pagan loyalty to the places and the people we once loved; yet we hope that eventually this undirected change will bring us the knowledge which will satisfy all our desires. How foolish this is – how it is bound to fail, and yet how God in his mercy confers signs of redemption even in his punishment of the sin – Spenser shows by suspending the narrative of Mutability and telling us a quaint tale about how the wood god Faunus one day tried to see Diana naked. It is a rule of Renaissance poetry: there are no digressions. Something about Faunus is meant to reflect upon Mutability. He too wants to see what he has no business seeing. That is not because he should remain ignorant, but because his seeing it on his terms would profane it. He can see Diana’s body, but only by wilful blindness to the holy. The plot is simple. Once upon a time in Ireland, back when that land was not yet ravaged by wolves and robbers and Catholics and people who hated English imperialists, the wood god Faunus bribed a river goddess, Molanna, to let him see Diana bathing after the hunt. The bribe was that he would unite her with her beloved river god, the Fanchin. (As the reader may know, rivers are always getting married; in Pittsburgh, for instance.) So Molanna placed Faunus in a fit spot for viewing, and, sure enough, he saw Diana: There Faunus saw that pleased much his eye, And made his heart to tickle in his breast, That for great joy of somewhat he did spy, He could him not contain in silent rest, But breaking forth in laughter, loud professed His foolish thought. (46.1-6) That’s an interesting reaction, that giggle: the nervous reaction of a fool, who suspects that he knows nothing about that mysterious “somewhat” he gazes upon. Diana and her nymphs look round, and see the satyr god. At which point he is in grave danger. If this were classical mythology, Diana would splash him with water from the stream and turn him into a deer, whereupon like Actaeon before him he would be torn apart by his own hounds. They do consider killing him; then they consider administering the fate worse than death (the fate that to this day makes rape a rare crime in Italy), but that would put an end to one kind of ordered change: the race of wood gods would die out. So they enact a kind of change that involves both justice and mercy, both a fall from grace, and the hope for redemption. They dress Faunus up as a deer and pursue him with loud hallooing through the woods; while they overwhelm the Molanna with stones. That, however, does not kill Molanna; it merely changes her course, and Faunus does arrange that desired marriage of hers with the Fanchin. So we should not be surprised by the tragicomic court scene which is to follow. All the creatures of Ireland, along with the nymphs and the satyrs and the goodly river gods and goddesses, and all the planetary gods, including even Pluto and Proserpina from the world below, show up at a place called Arlo Hill (“Who knows not Arlo Hill?” asks Spenser, tongue in cheek, 36.6), which could be anywhere, or everywhere – all the physical universe contained in microcosm upon an Irish hilltop. They can only be seated there, however, because Nature’s sergeant, Order, assigns to them their fit places. Already we sense that if Mutability makes a case for nihilism, she will lose. Indeed, her appeal to the god of Nature is itself a concession to law and to hierarchical order, and when we meet Nature we see why it must be so. For Nature is a mysterious figure, embracing both unity and plurality, both the multifarious world of things that can be seen, and the transcendent One that cannot be seen: Then forth issued (great goddess) great dame Nature, With goodly port and gracious majesty, Being far greater and more tall of stature Than any of the gods or powers on high: Yet certes by her face and physnomy Whether she man or woman inly were, That could not any creature well descry, For with a veil that wimpled everywhere Her head and face was hid, that mote to none appear. (7.5.1-9) In her sexual polyvalence, Nature is the Neoplatonic Venus hermaphroditus, representing that union of contrarieties, whereby mind embraces the variegated fecundity of the material world. But that is not all. Her face is veiled, says Spenser; perhaps because it was like a lion’s face, too terrible to view; but perhaps also because it was too beautiful, too dazzling. Of course it is meant to be both; and we sense a curious affinity here between the terrible and beautiful Mutability, and the terrible and beautiful Nature. More: we are meant to recall the words of Isaiah, who cried out that he must now die, because he had seen the face of God. Spenser has just such a theophany in mind. For some say that this deity could only be seen “like an image in a glass” (6.9), and that may well be true, says the poet, for this same day, when she on Arlo sat, Her garment was so bright and wondrous sheen, That my frail wit cannot devise to what It to compare, nor find like stuff to that, As those three sacred Saints, though else most wise, Yet on mount Thabor quite their wits forgat When they their glorious Lord in strange disguise Transfigured saw, his garments did so daze their eyes. (7.2-9) The countenance of Christ was changed on Mount Tabor, and the apostles, somewhat like the foolish god Faunus, quite their wits forgot – and Peter, ever impetuous, cried out that it was good for them to be there, and wished to prolong the moment of ecstasy, suggesting that they erect three booths for Jesus, Moses, and Elijah to dwell in. It is natural in us to desire a happiness that does not fade, that is not subject to change and decay. But the attainment of that happiness, as the moment of Transfiguration itself is meant to show, cannot come of our own. It is a gift, and, more than that, a gift that transforms the one who receives it. In a sense, it was not Christ who was changed, but rather the minds of the apostles, who would learn to see in this moment an intimation of the change transforming change, the resurrection of Jesus. The reference to Mount Tabor is most fitting, because we are like those poor apostles, living in change, yet hoping for that final change that leads us to the end for which we were made. What that means is that both pagan visions must be rejected, even as their partial truth is acknowledged: there is a cyclical rhythm to the things of this world, and things do fall apart; the rhythm itself is not perfect. But, as Sophocles and Lucretius could not see, and as modern man sees but confusedly, mistaking technological development for progress, and progress for salvation, the world is going somewhere. So Mutability, deferent to Nature (and unwittingly undermining her case) presents her evidence. First come the months in pageant, each one with its appropriate zodiacal sign, and its fit work for the season. In December we see that this temporal order is embraced by a greater liturgical and eschatological order: And after him came next the chill December, Yet he through merry feasting which he made And great bonfires, did not the cold remember, His Savior’s birth his mind so much did glad; Upon a shaggy-bearded Goat he rode, The same wherewith Dan Jove in tender years, They say, was nourished by th’Idaean maid: And in his hand a broad deep bowl he bears, Of which he freely drinks an health to all his peers. (41.1-9) It is not only a cycle of ordered change, as the farmer-poet Hesiod might have noted. It is a cycle of ordered change directed toward a consummation. There is a Savior whose birth gladdens the heart. December, then, is not the final month; not at all, for the year Mutability presents begins in March, the month of the Annunciation, when the history of salvation changes utterly, and the Word is made flesh, to dwell among us. Even Jove has the sense to argue that such change does not make Mutability’s case, for, as he says, the planetary gods govern the days and months and seasons by their regular influence. Then Mutability plays her final card. She claims that over this cycle is a kind of change that knows no purpose, but is mere decay. The old myths concerning these gods assert that they were all born at some time, when they assert anything certain at all. As for the planets the gods pretend to rule, they too are subject to alteration and decay, having wandered far from their old paths in the days when Ptolemy looked to the heavens. These facts are not in dispute. What is in dispute is their meaning. For Mutability, the meaning is clear: “Then are ye mortal born, and thrall to me” (54.1). But, true to the beauty of her nature, she submits herself to the verdict of the one who by right is higher than she is. She and all the creatures of the world turn to Nature to decide the issue. What hangs in the balance? Only whether the final word in the world is nothingness, pointlessness, decay and death, or whether change itself is the beautiful and variegated means by which God brings all changing things to their perfection. Nature suddenly looks up with a cheerful countenance, and speaks. She does not deny the reality of change. She denies the interpretation placed upon it by all would-be idolators of change, or by those whom change might cause to despair: I well consider all that ye have said, And find that all things steadfastness do hate And changed be: yet being rightly weighed, They are not changed from their first estate, But by their change their beings do dilate, And turning to themselves at length again Do work their own perfection so by fate: Then over them change doth not rule and reign But they reign over change, and do their states maintain. (58.1-9) Things change, but they do not change. The cycle returns, but it is not a cycle, for when things turn to themselves at length again they work their own perfection, and the fate by which they do so is the fatum or spoken word of a God infinitely beyond Jove and all the natural world. Things hate steadfastness, if that is to mean a death-like remaining fixed in place, but by their very moving in the world they maintain and perfect their states, and claim an ontological priority above change. The philosophical and theological point which Spenser is making is simple, and ancient, and brilliant: without things, there cannot be change; change presupposes something that perdures across the change. If Mutability were to rule, there would be no more Mutability. So Nature turns to that aspiring Titaness with words meant to soothe, addressing her with genuine affection: Cease therefore, daughter, further to aspire, And thee content thus to be ruled by me, For thy decay thou seekst by thy desire. (59.1-3) Yet even that is not sufficient, for there will be both a change and a steadfast constancy the like of which none of the creatures on Arlo Hill, nor all the gods and goddesses, nor even the Titaness of change, can imagine. Says Nature: But time shall come that all shall changed be, And from thenceforth none no more change shall see. (59.4-5) Then Nature vanishes, no one knew where. What do we make of it, then? A whimsical myth in the service of an old metaphysics? I think rather that we are encountering here the deepest heart of a fellow traveler to the grave, and beyond. As his life draws near its end, he thinks not of some program of political change, but of those transcendent goods that direct change towards its own good. He seeks neither more nor less change upon earth, but the final change, whereupon that city not named London or Dublin but New Jerusalem will descend from heaven adorned like a bride. He seeks to see what mortal eyes have never seen: the God of the Sabbath, who is also the God of Sabaoth, God of hosts, ever at rest, ever in mighty act. Here then, in the perfectly finished and perfectly unfinished canto eight, the number of the resurrection, are the last words Spenser ever wrote: When I bethink me of that speech whilere Of Mutability, and well it weigh, Me seems that though she all unworthy were Of the Heavens’ rule, yet very sooth to say In all things else she bears the greatest sway, Which makes me loathe this state of life so tickle, And love of things so vain to cast away, Whose flowering pride, so fading and so fickle, Short Time shall soon cut down with his consuming sickle. Then gin I think on that which Nature said, Of that same time when no more Change shall be, But steadfast rest of all things firmly stayed Upon the pillars of Eternity, That is contraire to Mutability, For all that moveth doth in Change delight: But thenceforth all shall rest eternally With Him that is the God of Sabbaoth hight: O that great Sabbaoth God, grant me that Sabbath’s sight. (8.1-2)