Beethoven

advertisement

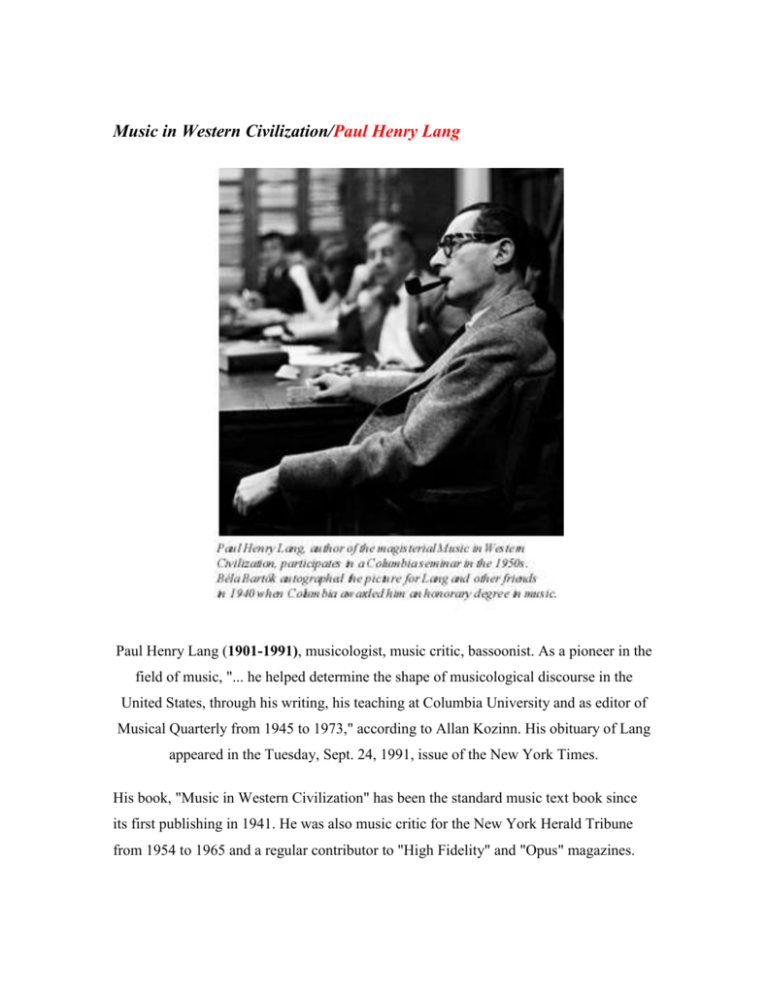

Music in Western Civilization/Paul Henry Lang Paul Henry Lang (1901-1991), musicologist, music critic, bassoonist. As a pioneer in the field of music, "... he helped determine the shape of musicological discourse in the United States, through his writing, his teaching at Columbia University and as editor of Musical Quarterly from 1945 to 1973," according to Allan Kozinn. His obituary of Lang appeared in the Tuesday, Sept. 24, 1991, issue of the New York Times. His book, "Music in Western Civilization" has been the standard music text book since its first publishing in 1941. He was also music critic for the New York Herald Tribune from 1954 to 1965 and a regular contributor to "High Fidelity" and "Opus" magazines. Born and educated in Budapest, Hungary, he began his career in 1922 as a bassoonist in Budapest Orchestras, but soon switched to the study of music history and musicology. Beethoven-Classicism and Romanticism THE mood that possessed Germany in the era of the Sturm und Drang provided the atmosphere for the young Goethe and the young Schiller. The conflict between man's natural claims and convention was realized and presented in various forms---Gotz von Berlichingen, Werther, Die Ranker, Kabale und Liebe. They derived their peculiar energy from the forces of their times--an era whose strongest incentives for a new life were in the spirit of opposition against existing ideas and institutions. Men found themselves in social circumstances that led the nation from economic slavery to a free modern order, from princely autocracy to a participation of the middle classes in the government, from the domination of the nobility and the courts to an assertion of the rights of the citizenry. In the ensuing campaign wide possibilities of progress opened up, with new aims on the horizon. More than anyone else, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) lived in this movement and was carried by it. There are natures which can walk erect only, to whom life would be worthless otherwise. In every note and every word of Beethoven, from the time he first became articulate, this erect stature and proud majesty of soul spoke with convincing assuredness. He felt, he knew, that his was a creative power to which all opposition in the matter with which he dealt must succumb; he formed it after his will and filled it with the contents of his soul. Thus was born a peculiar music, music that was the incarnation of strength and integrity. There is in these sounds nothing of the dreamy weaving of sentiments which casts such a spell over the musical lyricism of the romanticists; the emotions in them are sired by great and fully conscious intentions, governed by ideas, hence their unheard-of unity. The main impression they create is of greatness. No other musician has ever approached this gigantic, never-slackening will power; no one has ever coerced so impetuous, demonic a nature into following the dictates of his will under all circumstances, converting its energies into sheer creative power. This trait, the salient feature of his mental disposition, was, then, enhanced and conditioned by the temper of his times. The elemental necessity of his soul to rise above the individual through great, objective aims distinguishes him from his older classic brothers. But there was also the difference in the age, for, unlike the others, Beethoven did not grow up in the subjective Sturm und Drang era; when the young man came to Vienna, attention was focused on the more universal problem of social freedom. There is always something in him which stands above his personal fate; he was the poet of the ideal. In this idealism he identified himself with the point of gravity of his period, which stood for a friendly progress toward the realization of the dignity, freedom, and beauty of man, which it palpably believed capable of achievement. It is only natural that a man of such active nature, always proceeding from preconceived ideas, will take a stand relative to every great force of his time, will utilize it or will oppose it. The most classic of dramas, Goethe's lphigenia in Tauris, announces the redeeming force of pure humanity, Euripides's deus ex machina conquered by humanity. The exhilarating problem now was to elevate the individual into the universal. Egmont and Tasso perish, but Faust succeeds. Faust, the Promethean man, beholds Arcady, although his path has led over the dead body of Margarethe. He is Goethe himself, reaching the eternal peaks of knowledge through the wild Walpurgis Nights, now acquiescing in law and order, whose barriers he stormed with such vehemence. He is the universal, the eternal man who lives the whole gamut of human experience, the Everyman, not saved by divine misericordia but by his eternal humanity, which destroys Satan. As in Goethe and his Faust, one beholds this genius in Beethoven. Eighteenth-century classicism sought immersion, appeasement of the heart. Beethoven's harmonies, like Schiller's, are eruptive; these men were no longer made for a quiet life. The urge for freedom that dominated the second half of the eighteenth century lived in Beethoven as in the other classic geniuses. This humble son of a menial musician discarded the wig and raised his head as the first modern artist who felt himself the equal of princes, profoundly convinced of the dignity of man and fanatically believing in freedom. And his music echoes this personality tenfold. Goethe himself was stunned and frightened by this "untamed personality," and by this "grandiose, great, and mad music." Every one of Schiller's dramas, from the Robbers to William Tell, is a formidable protest; in all of them a single person or a whole people champions an idea. The heroic ideal which permeates Beethoven's whole being is the same, the heroism of the liberty-loving German classicism, and this keynote is manifested in every one of Beethoven's musical gestures. How truly heroic and uplifting they are as compared to the decorative and dazzling but exterior and even unconvincing fanfares of the French school of the Empire. The French were burnt out: all they could do was to stylize or be theatrical. Beethoven's Coriolanus and Egmont, his anonymous heroes of the Third Symphony, the Sonata Appassionata, and the Mass in C are worthy of the ancient epopoeia, for they stand at the summit of human nobility. Beethoven proved convincingly that true idealism is heroism; with him we reach the limits of the classic conception of the heroic and perhaps the ultimate limits of heroism expressed in music. He came as the herald of the nineteenth century, the musical prophet of will power. He rose from the spirit of the war for freedom, and, threatened with what for a musician is worse than death, he beseeched God to give him strength to "conquer himself." The firebrand and bacchant became a classicist through self-discipline. Beethoven was to a certain degree drawn to the spiritual sphere of romanticism. There can be no question as to the numerous threads that lead from him to the romanticists, but to count him among the latter amounts to a fundamental misreading of styles, for Beethoven grew out of the eighteenth century; the whole immense wealth of that century was concentrated in him, and what he did was to make a new synthesis of classicism and then hand it down to the new century. The romantic elements in the early Beethoven do not contradict his pure classicism, for the effects of the Sturm und Drang created a "romantic" crisis in all the great classicists. In his very first trios and piano sonatas that appeared as opus 1 and 2 (after a considerable number of earlier compositions, which were left unnumbered), the uncertainty as to his future course gave way to a definite profession of faith in classicism, clearly visible in his espousing of the ideals of three great classic masters, Haydn, Clementi, and Cherubini. It is in the nature of the classic genius that it organizes itself and everything around it. How much of the eighteenth century still lives in Goethe and Beethoven, how much of the naivete and fresh straightforwardness of the Enlightenment--and how truly were they still designers and not painters. All classicism rests on equilibrium--not a rigid but a living equilibrium of forces and functions. All classicism seeks relation, proportion, and form, achieving unity in the identity of form and material. The whole nature of classicism is a middle path, but not because of half measures or indifference, for the equilibrium is the result, and not the point of departure. The scales between the contending forces never stand still. The romantic is what overflows from the boiling cauldron of the overheated style of the period and forms its own world. It usually dissolves the classic elements. The sharply designed contours of classic melody are loosened; classic harmony abdicates its structural functions and becomes vacillating, even aimless, while on the other hand exhibiting a colorfulness and variety unknown to the classicist. The temptation to follow romantic voices was not missing in Beethoven, but there stood his tremendous will to mold, to carry the gospel of thematic logic to the limits of human power and understanding. These limits he reached at the end of his life, at the time when romanticism was a victorious reality. Unconcerned digression in tonalities without provision for a safe return is unknown to the classicist. He is always watching his compass to conduct his modulations and developments. This does not in the least mean a lack of variety or a stifling of the imagination. On thecontrary, it requires the greatest architectural skill and fantasy. The bolder the modulations, the more admirable the logic that is brought into play. The romanticists took over these principles and established a whole code of formal laws, but the essence of tonal logic, its really form-building qualities, were lost. We are only too conscious, especially in the larger sonata forms of the romantic composers, that after an indulgence in rich harmonic adventures they suddenly resort to their code of formulae and force their way back, for there must be a recapitulation and the subsidiary material must be brought back in the tonic key. We often say that Beethoven burst the forms, but such a statement is really meaningless, for with the classicists form is result and not aim. What seems to be enlargement and variant from the traditional is, in reality, new and does not rest on arbitrary acts but on necessity in order to frame the composer's thoughts. Thus, from Beethoven's point of view, it is as much "according to the rules" as the conventional form seems to the pedant. The romanticists were carried away by rhythm; seizing the natural emphases, they abandoned themselves to the pulsating alternation of certain patterns until, in the later works of Schumann (to cite one example), such patterns dominate whole compositions. Beethoven places his sforzati with dogged determination on the offbeats. Weight and accent do not appear to him as simple natural phenomena; they must be organized and elaborated according to his will. Nothing escapes his iron fist; no rhythmic pulsation is permitted to flow past uncontrolled, and even if meter and rhythm develop "naturally" they are merely permitted to do so. But all this is the unique privilege of the classicist; Haydn and Mozart were equally masters of their music. They were not led; they commanded. The romanticists searched every corner of their world, they infused themselves with its beauties, but they did not attempt to rearrange their universe; they surrendered themselves to it. Beethoven remained a classicist, and no matter how many threads lead from him to romanticism and from romanticism to him, he never became a romanticist. He never changed his belief in the duty of the creative artist, and while, in his last decade, the temptations became more intense and required Herculean self-discipline, the works of this period acquired a peculiar greatness from the inexorable will power which kept them intact. Occasionally this severe regimen caused an acute hypertrophy of will, rising to the highest tonal regions where tonal sensation proper, dominated by the energy of the elan, was all but lost. But no matter how deeply he was stirred or carried away, the rudder never slipped from his hands to whirl masterless. The great problem of nineteenth-century music was the union of poetry and music. The romanticists hoped to include mimicry, painting, and architecture in the universal art. The union of music and poetry was not new; for hundreds of years lyricism had been synonymous with it, and the dance had been wedded to music since time immemorial. There is, then, a line in art that tends toward the Gesamtkunstwerk. Yet this universal art is not the crowning of all arts, for music possesses a wide field where a greater verbal clarification of expression is not a gain. One might even say that the essentially musical is opposed to association with another art, for, as Schopenhauer has said, music conveys the idea itself, whereas the other arts present only its images. The limitations placed on music by such associations are of a varying degree, but one thing is certain: the most advanced form of this universal association of arts, the Wagnerian drama, cannot satisfy all our artistic desires. To Beethoven the association of words with music was of minor importance. His music remained, with a few exceptions such as Fidelia, instrumental music, even when a text was involved as in the Ninth Symphony, and his music is not enriched by such associations. Music was with him, as with the classicists in general, the immediate expression of creative activity; the creative problems that his imagination conjured up appear immediately as pure music. Later in the century the original incentive became literary, a literary conception conveyed by music. Beethoven created heroism in his Sinfonia Eroica, whereas Strauss conceived the life of a hero and proceeded to tell it in music in Ein Heldenleben. The innermost content of Beethoven's works cannot be expressed in words, for this content is the idea itself. Program music played an infinitesimal part in the works of the classic composers of the eighteenth century. Whenever a symphony was labeled with a program, as were Dittersdorf's descriptive symphonies, it usually ended in naive playfulness and imitation. Whenever Beethoven resorted to poetic allusions--in the sonata called Les Adieux, or in the Pastoral Symphony--every scrap of descriptive or associative material was incorporated organically in the body of the work. There is only one bona fide program composition in his oeuvre, the so-called Battle Symphony, a purely exterior piece de circonstance and perhaps his most insignificant work. The problem is of an entirely different nature when the relationship of words and music is association in a mutual task. In the foregoing chapter we discussed the purely musical conception of vocal music in the eighteenth century and the gradual development toward the literary. In the romantic era, the literary approach dominated all domains of vocal music, with the exception of Italian opera. Music joined a literary text, which was in charge of the shaping of the creative ideas. The duty of music then became to en-hance poetic expression by adding to it what words cannot express. The great Ninth Symphony with its choral finale created a controversy that, after more than a century, has not yet abated. The romantic apologists, led by Wagner, based their theories largely on the existence of this choral finale; Wagner declared that the very fact that Beethoven had to resort to human voices proved the insufficiency of pure instrumental music. "A human voice, with the clarity and confidence of speech, makes itself heard above the uproar of the orchestra," said Wagner, and he did not hesitate to claim that his own works, derived from this choral finale, began where Beethoven ended. The numerous "choral symphonies," from Spohr and Mendelssohn to Mahler, testify to the profound impression made by the Ninth Symphony on subsequent composers; but they also prove that this symphony, like many other works of Beethoven's regarded as romantic compositions, was really not understood. The listener not preoccupied with claims and counterclaims cannot fail to perceive the essential unity of the four movements. To him the entry of the voices does not change the general impression and certainly does not entail a fundamental change in principles. The employment of the chorus in the Ninth Symphony represents as little the union of poetry and music as the singing of the birds, the rippling of the brook, and the thunder make the Sixth Symphony into simple program music. Everything in the Pastoral Symphony is symphonically conceived, and no sooner does the lightning flash than its motif is thematically utilized and engulfed in the symphonic fabric. The same purely abstract symphonic conception rules the Ninth Symphony. The sufferings and trials of humanity we experience in the first three movements with the greatest intensity, although the chorus, announcing the joy of mankind, joins in the fourth movement only. The same human beings who sing here in words were present for Beethoven in the previous movements where he speaks of their tribulations in a purely instrumental language. And now he turns to them: "O Friends, not these sounds! Let us sing pleasanter and more joyful ones." Now they must sing with him, the human voices singing with the symphony. No one could call the final movement of the Ninth Symphony a setting of Schiller's ode, for the music did not arise from the poem. Rather the poem joined the music. The disposition of the finale is fully determined in the purely orchestral introduction followed by a set of variations that precede the vocal entry. Nothing happens here that Beethoven has not done before. Instrumental recitatives occur in some of his earliest works; they were common in the eighteenth century, and the reintroduction of themes from previous movements is one of the features of the piano sonata opus 101. The theme in itself, the theme of the "Ode to Joy," is a typically instrumental thought of purely symphonic qualities. Thus, by the time the voices enter, the whole course of the finale is determined. The text itself mattered little to Beethoven once he was actually proceeding with its musical elaboration. The first and most startling appearance of the human voice, the baritone solo alluded to by Wagner, sings Beethoven's own words. He selected but a few of the twenty-four verses that make up Schiller's ode, and these he arranged in a wholly arbitrary manner; there was only one thought in his mind, to distribute the words to suit the requirements of the music. This is, then, the antithesis of the union of poetry and music so fervently advocated by romanticism. The edifice of the classic symphony remains unshaken, entirely undisturbed by the voices. Like its sisters, the choral symphony unveils a drama of a personal, inner life in a form so pure, so free of all the accessories of life, as to be unmatched in any other art.