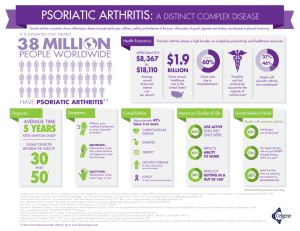

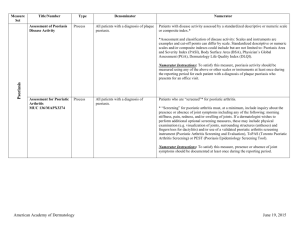

psoriatic arthritis

advertisement