Transatlantic implications

advertisement

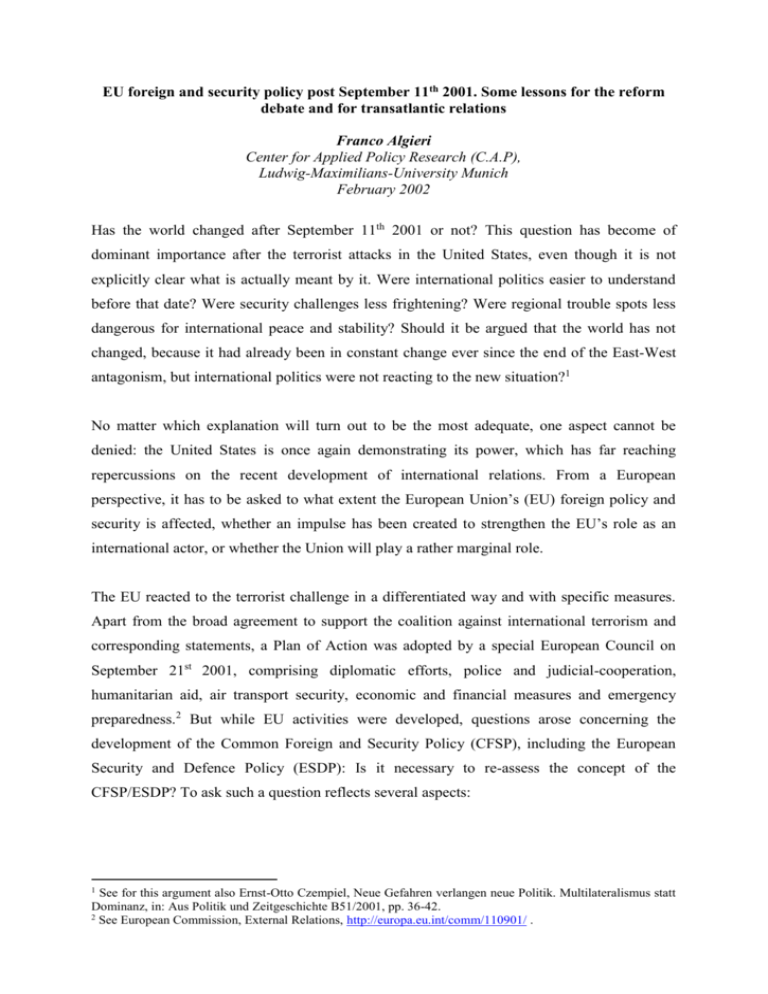

EU foreign and security policy post September 11th 2001. Some lessons for the reform debate and for transatlantic relations Franco Algieri Center for Applied Policy Research (C.A.P), Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich February 2002 Has the world changed after September 11th 2001 or not? This question has become of dominant importance after the terrorist attacks in the United States, even though it is not explicitly clear what is actually meant by it. Were international politics easier to understand before that date? Were security challenges less frightening? Were regional trouble spots less dangerous for international peace and stability? Should it be argued that the world has not changed, because it had already been in constant change ever since the end of the East-West antagonism, but international politics were not reacting to the new situation?1 No matter which explanation will turn out to be the most adequate, one aspect cannot be denied: the United States is once again demonstrating its power, which has far reaching repercussions on the recent development of international relations. From a European perspective, it has to be asked to what extent the European Union’s (EU) foreign policy and security is affected, whether an impulse has been created to strengthen the EU’s role as an international actor, or whether the Union will play a rather marginal role. The EU reacted to the terrorist challenge in a differentiated way and with specific measures. Apart from the broad agreement to support the coalition against international terrorism and corresponding statements, a Plan of Action was adopted by a special European Council on September 21st 2001, comprising diplomatic efforts, police and judicial-cooperation, humanitarian aid, air transport security, economic and financial measures and emergency preparedness.2 But while EU activities were developed, questions arose concerning the development of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), including the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP): Is it necessary to re-assess the concept of the CFSP/ESDP? To ask such a question reflects several aspects: 1 See for this argument also Ernst-Otto Czempiel, Neue Gefahren verlangen neue Politik. Multilateralismus statt Dominanz, in: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte B51/2001, pp. 36-42. 2 See European Commission, External Relations, http://europa.eu.int/comm/110901/ . First of all, a general scepticism regarding the EU’s foreign and security political capabilities. Examples are numerous and can be found on the level of the EU member states, on the supranational level with respect to the role of the institutions involved, on the side of third countries, in media comments as well as in the academic debate. Second, the EU’s role as a crisis manager in the Afghanistan conflict raised doubts about the coherence and strength of European foreign policy. For example, at the same time that the EU Troika was on a diplomatic mission in Islamic countries, the British foreign minister undertook his own initiatives. In the past, such a parallelism of European diplomacy was often criticised due to its weakening effects on the perception of the EU as a coherent foreign policy actor. This time, the argument runs in favour of parallel initiatives, i.e. additional activities by one or more member states are perceived as strengthening European foreign policy – based on the assumption, of course, that a common interest is expressed.3 Third, a further reason for scepticism is related to the results of the Capabilities Improvement Conference of November 2001. If there ever was a certain euphoria concerning the military capabilities that should be made available by EU and non-EU states to achieve the headline goal4, the results of the Capability Improvement Conference speak in favour of a more sober analysis. There is need for stronger efforts concerning forces, e.g. protection of forces deployed, commitment capability and logistics, and concerning strategic capabilities, e.g. command, control, communications and intelligence resources (C3I). To remedy these shortcomings, the member states agreed on a European Capability Action Plan5; nonetheless, one should not expect the existing problems to be satisfactorily solved in a short period of time. The recent controversial debate within and amongst EU member states on the purchase of the A400M military transport aircraft 3 See for example the interview with Chris Patten in: Sueddeutsche Zeitung, 29/30 September 2001, p. 5; Chris Patten, In defence of Europe’s foreign policy, in: Financial Times, 17 October 2001, p. 15. 4 “To develop European capabilities, Member States have set themselves the headline goal: by the year 2003, cooperating together voluntarily, they will be able to deploy rapidly and then sustain forces capable of the full range of Petersberg tasks as set out in the Amsterdam Treaty, including the most demanding, in operations up to corps level (up to 15 brigades or 50,000-60,000 persons). These forces should be militarily self-sustaining with the necessary command, control and intelligence capabilities, logistics, other combat support services and additionally, as appropriate, air and naval elements. Member States should be able to deploy in full at this level within 60 days, and within this to provide smaller rapid response elements available and deployable at very high readiness. They must be able to sustain such a deployment for at least one year. This will require an additional pool of deployable units (and supporting elements) at lower readiness to provide replacements for the initial forces.” Helsinki European Council 10-11 December 1999, Annexes to the Presidency Conclusions, Annex 1 to Annex IV. 5 See General Affairs Council with the participation of the Ministers of defence of the EU, Statement on improving European military capabilities, European capability action plan, Brussels, 19 November 2001. 2 indicates, as one example, that the EU still has a long way to go before being capable of handling military operations embracing all levels of the Petersberg tasks.6 The Spanish EU presidency has a comprehensive mandate to further develop CFSP/ESDP. But to find the necessary agreement between the interests involved demands time. In order to avoid frustration, it will be important to accept a longer-term perspective. Could EU forces be able to carry out full Kosovo-type operations without recourse to US assets by 2015? Would it be possible, in a period from 2015-2030, to achieve a progressive transfer of national decision-making, command and control competencies into a common structure, in which qualified majority voting in some form would be the rule within a common legal framework?7 Apart from accepting the above mentioned time dimension, the EU has realised that security policy will have to follow a comprehensive concept – September 11th has underlined it. A look at the non-military capabilities of EU external relations offers a broad range of instruments and policies available. However, what is still lacking is a strategic vision of the EU’s foreign policy. Article 11 of the Treaty on European Union defines the objectives of CFSP without reflecting a clear geopolitical thinking.8 It was stressed that “the EU has much more scope for preventing and resolving conflicts on its own continent than elsewhere” 9. Nevertheless, because of the high degree of global interdependence the EU is facing as a leading economic and trade political power, and in accordance with the objectives laid out in Article 11 TEU, the political, economic and societal stability of regions, no matter how near or far, is an essential interest of the EU. Therefore, the geographic extension of CFSP/ESDP needs to be clarified, which means to define whether the significance of this policy will be 6 See in this context the remarks of the president of the Military Committee presented at the European Parliament, in Agence Europe, 23 January 2002, p. 3. The Petersberg tasks comprise: humanitarian and rescue task, peace keeping tasks and tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including peacemaking. 7 See Bertelsmann Foundation (ed.), Enhancing the EU as an international security actor. A strategy for action, Gütersloh 2000. 8 Article 11.1 TEU: The Union shall define and implement a common foreign and security policy covering all areas of foreign and security policy, the objectives of which shall be: - to safeguard the common values, fundamental interests, independence and integrity of the Union in conformity with the principles of the United Nations Charter; - to strengthen the security of the Union in all ways; - to preserve peace and strengthen international security, in accordance with the principles of the United Nations Charter, as well as the principles of the Helsinki Final Act and the objectives of the Paris Charter, including those on external borders; - to promote international cooperation; - to develop and consolidate democracy and the rule of law, and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. 9 See Christopher Hill, The EU’s capability for conflict prevention, in: European Foreign Affairs Review 6, 2001, p. 331. 3 mainly concentrated on the enlarged EU’s closer neighbourhood or whether it is a policy with a global outreach. This implies asking whether it seems possible to think of Petersberg tasks in distant region, as for example Asia. Security in a comprehensive understanding implies, furthermore, that CFSP/ESDP cannot be limited to one pillar of the European treaty framework. On the contrary, there is a necessity for an overarching approach – which was further underlined following September 11th when Justice and Home Affairs became a central topic in the security debate. To close the gap between ‘common’ and ‘intergovernmental’ would thus imply the harmonisation of conflicting policy fields for a common interest. In the post-Nice reform debate it will be crucial to find a satisfactory model for the decisionmaking process through which the EU’s foreign and security political capabilities can be improved. Two major tasks exist: First, to develop a functioning concept for the interaction between the different actors and institutions involved, both in a vertical (between the national and supranational level) and in a horizontal direction (on the supranational level, e.g. between Council and Commission, as well as on the national level, e.g. between the member states). Second, closely linked with the first task, the decision-taking procedure has to avoid deadlocks, which brings up the question of an extension of majority voting and leads, furthermore, to the aspect of differentiated integration. A quite popular proposal is to reconsider the relationship and division of responsibilities between the High Representative for CFSP in the Council and the Commissioner for External Relations and ultimately merge both functions, linking it to a vice president of the Commission.10 It has been critically remarked that the tension between intergovernmental and Community competencies cannot be overcome with an actor like the High Representative for CFSP in the Council Secretariat, because such a structure inevitably creates more institutional complications.11 The High Representative, for his part, defined his role primarily as an actor assisting the presidency and the member states.12 Rivalries amongst these two actors do not See amongst others the European Parliament’s report concerning the reform of the Council, A5-0308/2001 final, 17 September 2001. 11 See in this context also the communication by Chris Patten, External relations. Demands, constraints, priorities, in: Agence Europe, Europe Documents 2193, 10 June 2000, p. 3. 12 See Javier Solana, The development of a CFSP and the role of the High Representative, Danish Institute of International Affairs, 11 February 2000, 10 4 give the impression of institutional consistency. “One thing is clear, that unless a way is found of merging the bureaucracies, the problem of ‘institutional’ consistency will continue to exist”.13 In case the decision-making and decision-taking mechanisms will not be reformed in a sufficient way – due to the well known lack of the political will of the member states – and CFSP/ESDP remains a ‘paper tiger’, the possibility that single member states start to act on their own in specific crises will be greater, even though an answer by the EU might be called for. Uncontrolled ad-hoc coalitions and activities outside the agreed institutional framework would damage the integration process enormously. Still, it is often difficult to go beyond a conventional understanding of the European integration process, even though a change of perspective is of vital importance if the Union’s capability to act and its policy-making process is to be improved – and not to forget, if the acceptance of European foreign and security policy amongst the EU citizens is to be guaranteed. The idea to apply enhanced cooperation to CFSP, as outlined in a rather limited form in the Nice Treaty, could turn out to offer an adequate concept in order to bring further integration steps and the enlargement of the Union into line.14 Assuming that enhanced cooperation can be progressively developed, this would allow member states willing to deepen cooperation to further communitarize certain fields of CFSP within a confined setting. This would represent a sort of learning phase for the future and a redefinition of integration. The experience gained with EPC has demonstrated that certain measures were implemented for intensifying political cooperation, then given a legal basis at a later stage. Enhanced cooperation in CFSP could produce a similar effect. In practice, it could prove that cooperation concerning the nonmilitary aspects of foreign and security policy is possible within a communitarian framework capable of meeting the challenges of international politics. Furthermore, it would provide an opportunity to handle the increasing number of particular interests in an enlarged EU. To sum up, enhanced cooperation in its present form needs to be transformed into a concept that will lead to a far reaching communitarization of CFSP for two motives: to strengthen and extend the foreign, security and (ultimately) defence political capabilities of the EU; 13 See Simon Nuttall, Consistency and the CFSP, London School of Economics, EFPU working paper 2001/3, http://www.lse.ac.uk/Depts/intrel/pdfs/EFPU%20Working%20Paper%203.pdf 14 See Franco Algieri and Janis Emmanouilidis, Setting signals for European foreign and security policy. Discussing differentiation and flexibility, CAP Working Paper, Munich, Center for Applied Policy Research, October 2000. 5 to avoid that ad hoc coalition building, which does not respect the agreed institutional and legal framework of the EU, becomes the typical pattern for crisis management. Transatlantic implications The European Union cannot be considered a foreign policy actor comparable to a single state. It would be more than risky to try to compare the United States’ foreign policy, not to mention the military dimension, with the EU’s foreign and security policy. Taking the above mentioned aspects into consideration, it should therefore be analysed what the United States can expect from the EU at this stage of CFSP/ESDP’s development. The concept of ESDP neither aims at a European army, nor is the development directed – at least for the moment – towards a military Union. The specific nature of the complex decision-making mechanisms, with interwoven actors and interests on different levels, is characteristic for today’s EU, which is in the midst of an uncompleted foreign and security political reform process where capabilities improve gradually and not at the same pace in all policy fields. ESDP is also not conceptualised as a challenge to NATO and transatlantic relations; rather, it is meant to be a supporting element. Of course, it needs to be acknowledged that a certain rivalry between the EU and NATO can become more prominent at the moment when European states do reconsider the need for two organisations, which – if NATO continues to turn more and more into a political organisation – follow quite similar interests. When it has become crystal clear that NATO can never offer the same quality – not to speak of economic benefits – and deepness of integration as the EU, when the EU counts more member states than NATO and when CFSP/ESDP has achieved significant progress, then the role of NATO will have to be questioned seriously. US foreign policy should thus seek to clarify to which degree and in which areas the EU is needed as a partner for international task sharing. Such a choice will depend largely on the way US foreign policy will be conducted, i.e. unilaterally or multilaterally. With a view to US foreign policy after September 11th 2001, some reject unilateralism as an option and demand cooperative engagement,15 while others observe that the US “commitment to multilateral action was tactical rather than strategic”.16 Much of the success of the transatlantic 15 See Francis Fukuyama, The United State, in: Financial Times 15./16. September 2001, weekend p I. Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Lindsay, Unilateralism is alive and well in Washington, http://www.brookings.edu/views/op-ed/daalder/20011220.htm [3 January 2002]; 16 6 relationship’s quality will depend upon whether the foreign policy concepts of the EU and the US turn out to be compatible or whether they are competitive. As the recent state of the development shows, European security and defence policy is not too challenging for the United States. Assuming that CFSP/ESDP will be developed fast and far reaching, then US foreign policy will have to realise that a specific model of foreign policy is determining the EU as an international actor that cannot be ignored any longer. 7