Strategic Outreach Roundtable and Conference Report

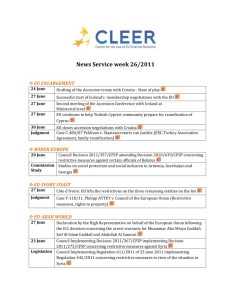

advertisement