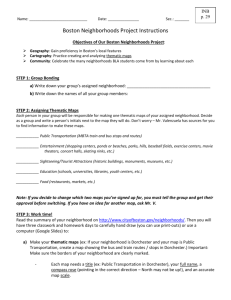

Literature Review - Center for Development of Human Services

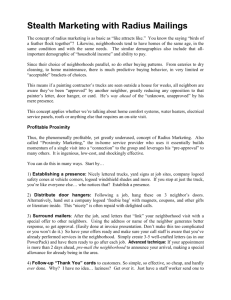

advertisement

Children and Neighborhood Context 1 CHILDREN AND NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT Literature Review Jackey Elinski, M.A. Doctoral Student Sociology Department State University of New York at Buffalo Michael P. Farrell, Ph.D Professor Sociology Department State University of New York at Buffalo Meg Brin: CDHS Child Welfare Administrative Director Tom Needell: CDHS Child Welfare Trainer Mike Rowe: CDHS Child Welfare Sr. Trainer Appointment: January 1, 2003 to June 30, 2003 This project was funded through a partnership between the Center for the Development of Human Services, Buffalo State College Research Foundation and the Sociology 1029071, Task 2) © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 2 Abstract Recently the impact of neighborhoods on the families that live in them has become a widely studied topic in the social sciences. With this neighborhood context theory in mind, researchers have paid particular attention to the connection between communities and their influence over child and adolescent development. They have explored areas such as how neighborhood composition influences family processes and parenting styles, how the presence or absence of neighborhood resources affects family and child success, and how the socioeconomic make-up of a neighborhood impacts the community’s degree of social cohesion and how this, in turn, affects children’s development. The following presents an overview of the current academic literature that focuses on how neighborhood context influences child and adolescent development in the areas of educational attainment, cognitive skills, crime, teenage sexual behavior, and labor market success. The different theoretical models that frame this research are explained and methodological concerns are addressed. In addition, a brief history of how this topic has come to be a much researched area in sociology is discussed. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 3 I. Introduction During the 1990s there was an increased academic interest in studying the impact of neighborhoods on children and adolescents. More specifically, researchers were interested in how poverty stricken neighborhoods played a part in shaping the life chances of the children who lived in them, since by 1990, 12% of families and 19.9% of children in the United States were living in poverty (Seccombe 2000:1094). Not only were social scientists concerned with the mechanisms by which neighborhoods influence children and adolescents, they were also interested in exactly what ways neighborhoods impact youths and what can be done to possibly moderate any “neighborhood effects.” Much of the literature on this topic credits Wilson’s 1987 book The Truly Disadvantaged as being the catalyst for this new flurry of research about neighborhoods. In this book Wilson attempts to explain the creation and expansion of the mostly African-American underclass in American cities since the middle of the twentieth century. He argues that the extreme social isolation of the members of the underclass brought on by changes in the United States’ economy is primarily to blame for this. According to Wilson, the shift from an industrial economy to a service oriented economy saw most of the industrial manufacturing jobs disappear from American cities. These positions, which were generally well paying jobs for unskilled workers, were mostly replaced with low wage service sector jobs and more skill intense jobs located out in the suburbs. As a result, many inner city residents lost their jobs and middle-class AfricanAmericans fled the inner cities in pursuit of the newly created suburban jobs. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 4 Those left behind in the city cores were faced with very limited employment opportunities and little contact with middle-class America. Therefore, as joblessness became rampant among the urban poor, poverty and the social evils associated with it became concentrated in the inner cities thus creating an underclass that is so socially isolated from other segments of society that a vicious cycle of concentrated poverty is almost certain to continue. Subsequent researchers studying neighborhoods have viewed the implications of Wilson’s argument about concentrated poverty as potentially effecting the life chances and developmental outcomes of the children and adolescents who grow up in such disadvantaged neighborhoods. While Wilson’s book may have ignited a flame, the 1990 analysis of the existent literature by Jencks and Mayer helped to create an explosion of interest in neighborhoods and their impact on children. In fact, so much research on this topic has been done recently that Sampson, Morenoff, and Gannon-Rowley (2002) contend that “the study of neighborhood effects, for better or worse, has become something of a cottage industry in the social sciences.” II. Overview of Theoretical Frameworks and Models of Neighborhood Effects In their analysis, Jencks and Mayer (1990) found that a number of theoretical frameworks are used by researchers when trying to decipher just how neighborhoods affect those who grow up in them. For example, some researchers see the behaviors and problems in a neighborhood as being contagious. Their epidemic models imply that individual behavior is linked to the behavior of others in the neighborhood. When negative behaviors persist, these models predict that problem behavior will infiltrate the © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 5 behaviors of the children and adolescents who reside in these neighborhoods and negative behavior will beget negative behavior. According to Small and Newman (2001), epidemic models, as well as other socialization models, tend to view individuals as “relatively passive recipients of powerful socializing forces, suggesting that neighborhoods mold those who grow up in them into certain behavioral patterns” (p. 33). Therefore, according to epidemic models, children and adolescents can “catch” the negative behaviors of their neighborhood peers and they will then be socialized into behaving in similar negative ways. Other researchers, according to Jencks and Mayer (1990), use collective socialization models to explain how neighborhoods influence residents. These predict that the level of social organization in a neighborhood influences children and adolescents. Baumer and South (2001) assert that these models emphasize “the impact of parents and other adults in the community as both family role models and as agents of social control” (p. 541). According to this model, the higher the level of neighborhood social organization, the more positive the outcomes for the youth that live in the area. However, low neighborhood social organization, indicated by such symptoms as the absence of adult mentors, adult supervision, and the lack of adult daily routines that reflect “mainstream” lifestyles, impacts negatively on children and adolescents. According to Newman (1999) a lack of successful adult role models in a socially disorganized neighborhood leaves the children and adolescents of the neighborhood less likely to foresee themselves as successful adults. Therefore, these collective socialization models predict that © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 6 neighborhood adults are instrumental in socializing children and adolescents into becoming successful adults. Another theoretical framework that Jencks and Mayer (1990) identified as in use with regard to studying neighborhood effects is the use of models of competition. These predict that neighbors must compete for community resources. This implies that the life chances of economically disadvantaged youths may be hurt by the presence of more affluent neighbors who are more readily able to compete for scarce neighborhood resources. Relatively less advantaged neighborhood youths, according to these models, will be left behind, as those who are more successful in obtaining and utilizing community resources will be the ones who reap any benefits. Closely related, Jencks and Mayer (1990) also noted that neighborhood institutional models have been in use. These focus on how adults from outside of the neighborhood treat and influence children through their work in neighborhood institutions such as schools, libraries, and the police force. They posit that adults who come into the neighborhood to work may have preconceived notions about poor children in poor neighborhoods and may react to them accordingly. According to these models, the presence or absence of such adults may affect the children and adolescents in disadvantaged neighborhoods. According to Small and Newman (2001), these institutional models “focus on how individual agency is limited by neighborhood environment,” while socialization models “explain how neighborhood environments socialize individuals” (p. 33). © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 7 And lastly, Jencks and Mayer (1990) identified that social scientists have used relative deprivation models to explain how neighborhoods impact the children and adolescents who live in them. As with models of competition, these models too imply that the presence of affluent neighbors will hurt the life chances of economically disadvantaged youths. When poor children, as well as adults, judge that they have less or are failures compared to their affluent neighbors, this will adversely affect them. However, if their neighbors are on an equal socioeconomic playing field or are economically worse off then they are themselves, children, as well as adults, will judge themselves more favorably. Much of the research on neighborhood effects that has been done since Jencks and Mayer published their review still uses these theoretical frameworks that they identified. In addition, considerable amounts of the more current research still concentrates on the five areas that Jencks and Mayer focused on in their analysis when estimating the effects of neighborhoods on children and adolescents in their 1990 publication. These areas are educational attainment, cognitive skills, crime, teenage sexual behavior, and labor market success. Even now, though more than a decade has passed since the classic work of Jencks and Mayer, researchers in this field are still preoccupied with finding out if these outcomes are influenced by the neighborhood context in which children and adolescents grow up in. The following sections of this paper will present an overview of what Jencks and Mayer found in their 1990 review of the academic literature concerning children and neighborhoods. In addition, more recent research will be presented that focuses on the © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 8 five aforementioned areas of research concerning children and adolescents and neighborhood effects: educational attainment, cognitive skills, crime, teenage sexual behavior, and labor market success. III. Neighborhood Effects and Educational Attainment In their review of the literature that existed prior to 1990, Jencks and Mayer found that some of the earliest research on neighborhood effects looked at education. These early studies examined whether a high school’s mean socioeconomic status had an impact on students’ plans to attend college. However, different studies yielded different results. For example, after analyzing the existent literature, Jencks and Mayer concluded that students in higher socioeconomic status neighborhoods expected to complete more years of education than did students in other neighborhoods, even after their family characteristics were controlled for. However, they also found that a “high school’s social composition, in contrast, has very little effect on a student’s chances of finishing high school or attending college” suggesting that “neighborhood mix matters while school mix does not” (Jencks and Mayer 1990:137). In addition, they also found that attending a racially mixed high socioeconomic status high school might be more beneficial to African-American students. While attending these schools does not alter college plans for European-American students, African-American students enrolled at such schools appear to be more likely to plan to attend college than their counterparts in other high schools. In the end, however, according to Jencks and Mayer (1990), “teenagers who grow up in affluent © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 9 neighborhoods end up with more schooling than teenagers from similar families who grow up in poorer neighborhoods” (p.174). Similar results regarding school and neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics have been echoed in more recent research. For example, Brooks-Gunn et al. (1993) found support for collective socialization theories that suggest that the absence of affluent families in a neighborhood is more detrimental to child and adolescent development than is the presence of low-income families, which epidemic theories, models of competition, and relative deprivation frameworks posit. Specifically, they found significant effects of affluent neighbors on adolescent school leaving that persist even after the socioeconomic characteristics of students’ families were controlled for. In addition, contrary to what Jencks and Mayer concluded, their results suggest that the benefit of affluent neighbors in regard to school leaving is restricted to European-American students. Other recent studies too, have yielded similar results. Duncan (1994), for example, found evidence that high neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics are positively associated with educational attainment levels for adolescents. Ensminger et al. (1996) found this to be true even when studying a group of adolescents that was predominantly African-American. And Crane (1991) found that when the percentage of professional and managerial workers in a neighborhood falls below 5%, neighborhoods have a more significant negative influence on resident students’ school leaving. In addition, according to Rosenbaum and Harris (2001), after leaving Chicago’s public housing, mothers who moved to higher-income neighborhoods reported that their children were more likely to graduate from high school than were children in the © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 10 neighborhoods that these mothers had recently moved from. All of these results suggest that theories of collective socialization may be on target. It seems that affluent neighbors have a positive impact on students’ educational attainment. Ainsworth (2002) also found support for theories of collective socialization. In his study aimed at exposing neighborhood characteristics that influence educational achievement and the possible mechanisms that mediate these neighborhood effects, he concluded that “the presence of high- [socioeconomic] status residents in the neighborhood plays a statistically important role in students’ academic achievement” (p. 132). For example, he found that while family socioeconomic status is important in predicting the time children spend on homework and also their academic achievement, so too is the socioeconomic status of their neighbors. For instance, his results indicate that a greater number of high socioeconomic status residents in a neighborhood strongly predicted more time spent on homework as well as higher math and reading test scores. According to Ainsworth, his results indicate that “the number of neighborhood highstatus residents rivals the predictive power of many family and school factors that are often cited in the educational literature” (p. 132). While these researchers and others (Aaronson 1998; Garner and Raudenbush 1991; Gonzales, et al. 1996; Kasarda 1993; Rosenbaum and Harris 2001) have concluded from their studies that neighborhoods do in fact matter when it comes to the educational attainment and achievement of neighborhood children and adolescents, others (Ginther, Haveman, and Wolfe 2000; Jencks and Mayer 1990; Solon, Page, and Duncan 2000), however, do question the robustness of the relationship between neighborhoods and © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 11 educational outcomes. However, even after concluding that the “complete equalization of neighborhood backgrounds would leave inequality in educational attainment at more than 90% of its current level” and cautioning that “no one should be under the delusion that even total elimination of disparities in neighborhood background would get rid of most of the inequality in educational attainment,” Solon et al. (2000) do concede that “even if neighborhood correlations for other outcomes turn out to be as small as that for education, this does not deny that neighborhoods matter to some degree” (p. 391.) With this question of robustness in mind, it is evident that further research is still needed when it comes to neighborhood effects and child and adolescent outcomes in this and other areas. IV. Neighborhood Effects and Cognitive Skills Once again, Jencks and Mayer found evidence of contradictory results when they looked at the studies of neighborhood effects on child and adolescent cognitive skills. They found that outcomes depended considerably on the ages and races of students. They reported, for example, that a high school’s mean socioeconomic status has little effect on the amount that European-American students learn in high school. In contrast, it may have a significant impact on the amount that African-American high school students learn. In addition, they concluded that the cognitive growth of both AfricanAmerican and European-American elementary school students is influenced substantially by their school’s mean socioeconomic status. More recently, researchers have looked at child and adolescent IQ scores and school achievement in relation to neighborhood context. Brooks-Gunn et al. (1993) © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 12 found that having affluent neighbors had significant effects on childhood IQ. This was true even after family-level differences were controlled for. In addition, Halpern-Felsher et al. (1997) and Entwisle, Alexander, and Olson (1994) found that neighborhood socioeconomic status is positively associated with high school students’ grade point averages, math scores, and basic skills. Furthermore, both of these studies found evidence to indicate that neighborhood effects in this area are stronger for boys than they are for girls. In addition, Chase-Lansdale et al. (1997) found that the racial and ethnic composition of a neighborhood can have consequences for the academic achievement for the students in the neighborhood. According to their research, they found that higher levels of racial and ethnic diversity in a neighborhood were negatively associated with African-American boys’ academic achievement. In their study of the verbal and behavioral abilities of a national sample of Canadian preschool children, Kohen et al. (2002) found evidence to support that these areas too are impacted by neighborhood residence. Even after controlling for familylevel sociodemographic characteristics, they found significant relationships between neighborhood characteristics and verbal and behavioral competencies. Verbal ability scores were “positively associated with residing in neighborhoods with affluent residents and negatively associated with poor residents in neighborhoods with low cohesion” (p. 1844). In addition, they found that problem behavior scores “were higher when children lived in neighborhoods that had fewer affluent residents, high unemployment rates, and neighborhoods with low social cohesion” (p.1844). Though the neighborhood effect © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 13 sizes were small (approximately 3% of the variability in child outcomes), these results are consistent with findings in the United States. They suggest that the presence of affluent neighbors is beneficial to the developing child. Similar results were also found in the United Kingdom as well. McCulloch and Joshi (2001) examined the cognitive test scores of children ages 4-18 in a national sample from the British National Child Development Study. They found that neighborhood characteristics were significant predictors of cognitive test scores, particularly among very young children. For children aged 4-5 years, those living in the “topmost quintile of deprived neighbourhoods show a decrease of 6 percentage points in their test scores” (p. 587) when compared to those children living in the more affluent neighborhoods. For children 6-9 years old, those in the “most deprived quintile of deprived neighbourhoods have test scores 3-4 percentage points lower” than those in the least deprived areas (p. 587). However, for children ages 10-18, there were no statistically significant differences in test scores among different types of neighborhoods. However, while McCulloch and Joshi (2001) did find evidence of neighborhood effects when it came to children and cognitive skills, they also found that these are much weaker than the estimated effects of family-level conditions. They therefore caution that “families should be viewed as the key agents in promoting positive development in children” (p. 579). Duncan, Boisjoly, and Harris (2001) would make a similar plea. In their study of a nationally representative sample used to determine the correlations in vocabulary skills and delinquent behaviors between peers, siblings, schoolmates, and neighbors they found © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 14 that both neighbor and grademate correlations were small. In addition, they found that while peer correlations were significantly larger than grademate and neighbor correlations, they were not as large as most sibling correlations. They therefore concluded that their data “suggests that family-based factors are several times more powerful than neighborhood and school contexts” (p. 437) in affecting adolescents’ vocabulary skills and behavior. The findings of Chase-Lansdale et al. (1997) would seem to validate the models of competition and relative deprivation that Jencks and Mayer reported were woven throughout much of the research on neighborhood effects researchers prior to the 1990s. Meanwhile, the research described above by Brooks-Gunn et al. (1993), Halpern-Felsher et al. (1997), Entwisle, Alexander, and Olson (1994), and Kohen et al. (2002) lends support to models of collective socialization and institutional resources models. However, the findings of McCulloch and Joshi (2001) and Duncan et al. (2001) serve to highlight the notion that much research is still needed in this area to determine how and if neighborhood effects exist, and if so, just how much they influence the cognitive abilities of children and adolescents. V. Neighborhood Effects and Crime In their analysis of the existent literature prior to 1990, Jencks and Mayer also did a review of the research about teenage crime. While they added a cautionary note proclaiming that more and better studies were needed at that time about how neighborhoods influence teenagers and their propensity to commit crimes, they nonetheless detailed the results found in studies of crimes committed by adolescents in © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 15 Nashville in the 1950s, Chicago in 1972, and in Baltimore from 1978 until 1980. These, they said, were the best studies to have been completed to date. According to their review, Jencks and Mayer concluded that if a EuropeanAmerican adolescent attended an affluent high school, in Nashville in the 1950s at least, he was less likely to behave in such a way that the county courts would judge him to be delinquent. This was especially true for low-socioeconomic status male students who attended high-socioeconomic status high schools. However, Jencks and Mayer also pointed out that the results of this particular study might be exaggerated because the authors of the study failed to control for many individual-level socioeconomic factors. In addition, Jencks and Mayer noted research that concluded that in Chicago in 1972, residing in a poor neighborhood would increase the chances that middlesocioeconomic status adolescents would have reported having committed serious crimes while it would lessen the chances that low-socioeconomic status teenagers would have committed similar crimes. They suggested that this might be the result of relative deprivation and competition. According to this view, these low-socioeconomic status adolescents living in higher socioeconomic status neighborhoods would be more likely to commit serious crimes because they are in competition with their more affluent neighbors. However, in lower-income neighborhoods, these same youths are less likely to commit such crimes because they do not judge themselves to be any worse off than their neighbors. The study of re-arrests among ex-prisoners in Baltimore between 1978 and1980, meanwhile, had Jencks and Mayer concluding that neighborhoods did not matter when it © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 16 came to recidivism rates. Regardless of the household income characteristics, percentage of white-collar workers, or housing prices in the neighborhoods that they moved to once they were released from prison, the recidivism rates of young men were not influenced by their neighborhoods. Not only did researchers find no links between these neighborhood characteristics and the chances that the former prisoners would be arrested again, they also did not appear to impact on the kinds of crimes that they were likely to be charged with upon their re-arrest. These results seem at odds with the epidemic models that would predict that the ex-prisoner would be more likely to commit crimes while living in low-socioeconomic status neighborhoods because of the problem behavior that surrounds him. In addition, it is at odds with the relative deprivation models that would predict that ex-offenders living in higher-income neighborhoods would be more likely to commit crimes because they are surrounded by more advantaged neighbors. Recidivism aside, recent research too has helped lend support to the idea that neighborhood effects exist when it comes to adolescent delinquent and criminal activity. For example, after studying neighborhoods in Chicago and Denver, Elliott et al. (1996) found that neighborhood characteristics, such as levels of informal social control, have a substantial influence on adolescent problem behaviors. In addition, Sampson et al. (2002) concluded that their own review of the current literature on neighborhood effects points to links between neighborhood process and crime. They state that their analysis of existent literature reveals that neighborhood social cohesion, informal social control, institutional resources, and routine activity patterns are © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 17 all related to crime. Furthermore, earlier, Sampson and Groves (1989) found that in their study of two groups of British adolescents, the more ethnically diverse one’s neighborhood was, the more likely a youth was to engage in criminal activity. Ludwig, Duncan, and Hirschfield (1998), using data from the Congressionally mandated Baltimore Moving to Opportunity demonstration program, found that when African-American teenage boys moved from public housing in high-poverty neighborhoods to low-poverty neighborhoods, they were less likely to be arrested for violent crimes than were their counterparts still living in public housing. In addition, those who moved to lower- or middle-income neighborhoods were less likely to commit nonviolent and non-property crimes than were their teenage neighbors left behind in public housing. These results support collective socialization and institutional resource models while strongly challenging relative deprivation models. In Baltimore at least, it seems that when African-American teenagers move from public housing located in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, affluent neighbors are a positive influence unlike the relative deprivation and competition models would predict. Sampson’s 1997 study of eighty Chicago neighborhoods further supports collective socialization models. In his multi-level assessment of these neighborhoods he concluded, “even after adjusting for the effect of prior levels of crime in the neighborhood, informal social control [over adolescents] emerged as a significant inhibitor of adolescent misbehavior” (p. 242). Sampson also concluded that informal © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 18 social control mediated as much as 50% of the effect of residential stability when it came to rates of juvenile delinquency. Further supporting the use of collective socialization models to explain how neighborhoods impact on adolescents when it comes to delinquent behavior is Kowaleski-Jones’ 2000 study o f how community resources influence problem behavior among high-risk adolescents. She found that neighborhood residential stability characterized by few neighbors moving in a five year time span, decreased adolescent risk-taking and aggressive behavior, regardless of how disadvantaged neighborhoods were. This implies that since adult residents have been neighbors for lengthy periods, they are more likely to know each other and to exert informal social control over neighborhood youths as well to act as adult mentors and supervisors. In addition, Brody, et al. (2001) further lend support to the validity of using collective socialization frameworks when assessing neighborhood effects and delinquency. While they found that living in a poor neighborhood is associated with a greater likelihood that a child will associate with deviant peers, they also found that even in the poorest neighborhoods, higher levels of neighborhood collective socialization can lessen the likelihood of association with deviant peers. However, contrary to what these theoretical frameworks would predict, living in a more affluent neighborhood is not always necessarily a predictor of more positive child and adolescent behaviors. For example, Ennett, et al. (1997) looked at rates of early adolescent alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. They found, contrary to their hypothesis, that lifetime alcohol and cigarette use was higher in schools that were located © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 19 in more affluent neighborhoods. In neighborhoods where parents reported high levels of neighborhood resources, social support from neighbors, and neighborhood safety, alcohol and cigarette use among adolescents was higher than it was in less advantaged neighborhoods. As they point out, “These findings suggest the need for early prevention programs in schools or areas that typically may not be perceived as being ‘at risk’ “ (p. 68). And they also suggest that our theories of how neighborhoods influence children and adolescents may not be sufficient to fully explain or measure neighborhood effects on juvenile behavior and delinquency. VI. Neighborhood Effects and Teenage Sexual Behavior Jencks and Mayer concluded that, with regard to teenage sexual behavior, living in a poor neighborhood does matter. Their analysis of the literature suggests that teenage girls who live in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to have children than are teenage girls of similar socioeconomic and racial backgrounds living in more affluent neighborhoods. Furthermore, they said that the existent literature confirmed that teenage girls living in very poor neighborhoods were more likely to engage in sexual activity at an earlier age than were girls living in more privileged neighborhoods and that they were less likely to use birth control. In addition, they also found that neighborhood and school racial characteristics also had an impact on teenage sexual activity. For example, European-American fifteen and sixteen year olds were more likely to have engaged in sexual activity if more than one-fifth of their classmates were African-American. In addition, African-American fifteen and sixteen year olds in predominantly African-American schools were more © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 20 likely to have engaged in sexual activity than were their counterparts who attended predominantly European-American schools. While Jencks and Mayer concluded that neighborhood effects are stronger predictors of teenage sexual activity than they are of educational attainment, cognitive skills, and teenage criminal activity, more current research suggests the same. For example, Brooks-Gunn et al. (1993) found evidence to support the notion that as the number of affluent neighbors decreases, the likelihood that adolescent girls would have children increases. In addition, Crane (1991) once again found evidence that neighborhoods may impact children of different races differently. He concluded, for instance, that AfricanAmerican girls may be more likely to be negatively influenced by neighborhoods in this regard than are European-American girls. Additionally, he suggests that neighborhood effects may be strongest for African-American girls living in areas of concentrated poverty in inner cities. Meanwhile, Ku et al. (1993) found that unemployment rates in a neighborhood are also linked to teenage sexual activity. Specifically, they found that when unemployment rates were high, there was a positive association with neighborhood boys fathering children and neighborhood girls having children. The evidence that Jencks and Mayer report, as well as the results of more recent research points to the positive impact of having affluent neighbors in terms of delayed sexual activity and child bearing. This suggests that the epidemic models may be valid. As negative behaviors run rampant in a neighborhood, adolescents may be more likely to © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 21 engage in these behaviors themselves. In addition, however, collective socialization models that suggest that the presence of neighbors who can act as role models for children and adolescents also seem to be supported by the research on neighborhood effects on teenage sexual activity. However, as South and Baumer (2000) found in their study using longitudinal data from the National Survey of Children, neither parental supervision nor a child’s attachment to school or educational aspirations mediated the negative impact of disadvantaged neighborhoods when it came to adolescent childbearing. Even with the presence of adult role models and supervision, teens in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods were more likely to become adolescent parents. However, this study does support the epidemic theory of neighborhood effects in that it also found that “the positive effect of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage on the timing of young women’s first premarital birth can be attributed to the attitudes and behaviors of peers and to young women’s more tolerant attitudes toward unmarried parenthood in distressed communities” (p. 1379). Notably, South and Baumer (2000) also concluded that nearly two-thirds of the variance in premarital childbearing among the different racial groups can be attributed to the fact that different racial groups tend to live in neighborhoods of differing socioeconomic quality. Brewster (1994) found similar results in her examination of the role of neighborhoods in racial differences in teen sexual activity among girls. She asserts that the results of her study suggest that “race differences in adolescent sexual © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 22 activity and its negative consequences will persist as long as American housing patterns remain segregated” (p. 422). Brewster, Billy, and Grady (1993), after looking at a national sample of European American women, found that adolescent girls who live in neighborhoods that provide few opportunities and exhibit lower levels of social control are more likely to engage in sexual activity than are their counterparts in more advantaged neighborhoods. Hogan and Kitagawa (1985) found similar results for African American teenage girls. They found that girls from high-risk environments (measured by neighborhood residence, socioeconomic status, and family-level variables) have 8.3 times the pregnancy rates than do girls from low-risk environments. This study too lends support to epidemic models of neighborhood effects. Teitler and Weiss (2000), however, could not find robust support for neighborhood effects on teen sexual behavior when they used the 1993 Philadelphia Teen Survey to examine how much census tracts (commonly used as a proxy for neighborhoods) and schools affect adolescents’ timing of first sexual intercourse. On the contrary, when it comes to sexual behavior, they assert that neighborhood effects “exist only to the extent that they determine the type of school an adolescent attends [and that] school effects are primarily a function of racial composition and school type” (p. 112). They contend that it is the school environment that matters more than the neighborhood when it comes to adolescent sexual activity. They concluded that the differences in European American and African American teen sexual behavior can be explained by the fact that in Philadelphia, white youths are more likely than their black counterparts to © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 23 attend different types of schools. Again, conflicting evidence from empirical studies indicates that more research is needed to fully appreciate how and to what extent neighborhoods impact youths. VII. Neighborhood Effects and Labor Market Success Jencks and Mayer could find only five studies that examined the impact of neighborhoods on the eventual labor market success of adolescents. The conclusion that they drew from the limited research in this area was that neighborhoods do not seem to matter much. For instance, they found that the median income of a neighborhood does not have a significant impact on males’ eventual economic success once the racial mix and welfare-dependency rate in a neighborhood was controlled for. Nor did they find any evidence to suggest that a school’s racial mix or mean socioeconomic status significantly impacted eventual economic success. However, they did state that growing up in a predominantly African-American neighborhood or in a neighborhood with a high level of welfare-dependency probably does limit the eventual earnings of both European-American and African-American young men. These two neighborhood characteristics, however, appear to be the only that influence youths in terms of their eventual labor market earnings according to Jencks and Mayer. According to Ellen and Turner (1997), more recent research suggests that the neighborhood one presently lives in may be more important in terms of labor market success than the neighborhood where one grew up. Both Ellen and Turner and Sampson et al. (2002) point to the importance of establishing social networks in one’s © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 24 neighborhood in order to capitalize on employment opportunities. However, Ellen and Turner contend that any neighborhood effects that do exist may not persist if one moves to a new neighborhood where these important social networks can be established. Rosenbaum (1995) presented similar evidence from the Gautreaux Program in Chicago, which was the precursor to the national Moving to Opportunity program. His analyses demonstrated that when children who grew up in inner-city public housing moved to the suburbs of Chicago, both their educational and work prospects were improved. Both adults and adolescents who moved as part of the Gautreaux Program were more likely to be employed than were their counterparts who did not move from public housing. Again these findings lend support to the notion that having more affluent neighbors is beneficial to the developmental outcomes and life chances of children and adolescents. Therefore, models of collective socialization and neighborhood institutional resources are once again supported. In addition, if it follows that important social networks that lead to jobs are not available in less advantaged neighborhoods, another theoretical framework that Jencks and Mayer identified – models of competition – are also supported by the literature on neighborhood effects on the labor market success of adolescents and young adults. Vartanian’s 1999 research meanwhile lends support to epidemic models of neighborhood effects. Using linked data from the U.S. Census and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, he examined possible influences of neighborhoods on labor market outcomes for young adults. He found that growing up in the most disadvantaged © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 25 neighborhoods had a negative impact on labor market and economic outcomes as adults. His results also indicated that “Adolescents in the poorest neighborhoods…earned far lower wages and had lower income-to-needs than those in even slightly more advantaged neighborhoods” (p. 164) even after educational levels were controlled for. In addition Quane and Rankin (1998) found support for the epidemic theory of how neighborhoods influence labor market success as well. They were able to “demonstrate that poor neighborhoods are more likely to have higher proportions of youth that downplay the importance of education” (p. 783) and that this in turn contributes to lower expectations about their futures. However, they cautioned that they were unable to find evidence indicating a direct effect of neighborhood poverty on normative behavior expectations. Once again, however, since many questions about neighborhoods and their impact on the eventual labor market success of the children who grow up in them remain unanswered, further research is needed. VIII. Neighborhood Effects and Parenting Strategies Research that stresses the importance of social networks within neighborhoods highlights the important implications of Wilson’s (1987) argument about the social isolation that many are experiencing today in American inner cities. Regardless of which model they seem to support, the research on neighborhood effects lends credence to Wilson’s theory that the concentrated poverty that now plagues many American cities will be with us for a long time if major changes are not made. Seeing as how the literature supports the idea that neighborhood effects do exist and do influence child and adolescent life chances to some extent or another, it seems unlikely that those other than © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 26 the most resilient children will be able to escape the vicious cycle of poverty and disadvantage that Wilson wrote about. However, other research suggests that there are strategies that can be used by parents in disadvantaged neighborhoods that may serve to lessen the impact of neighborhoods on child and adolescent development. For example, Jarrett (1999) has identified “community bridging” parenting techniques that can be used as effective strategies to help combat the negative influences of neighborhoods on youths. These techniques include youth-monitoring strategies, resource-seeking strategies, and in-home learning strategies. Some parents who have been successful in moderating the negative impact of their inner city neighborhoods on their children have used youth-monitoring strategies. According to Anderson (1989), parents who have turned to this strategy are known throughout their neighborhoods to be very strict. They know where their children are at all times and always keep a watchful eye on them. For example, they may set rigid curfews for their children in order to keep them off the streets. In addition, they may keep close tabs on their children by taking an active role in promoting positive friendships for their children. Anderson (1989), for instance, describes how effective parents in inner cities often reject friends of their children who do not appear to be positive influences while they actively promote friendships with other children whom they judge to be more acceptable. In addition, Furstenberg (1993) found that parents who raise children who are able to overcome their poor neighborhoods often use another youth-monitoring strategy. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 27 These parents chaperone their children during their interactions with their neighborhoods. And as Jarrett (1999) describes, in order to help promote a sense of autonomy, some parents relinquish their chaperoning duties to their other children. These parents have their children monitor each other in hopes that they will keep each other away from the negative influences of their neighborhoods. Meanwhile, other parents use resource-seeking strategies to help promote the development of their children and adolescents. Parents who employ this technique in disadvantaged neighborhoods actively look for programs and opportunities for their children both inside and outside of their neighborhoods. For example, they may encourage their children to participate in church activities or to take part in athletic programs in order to keep their children’s interactions with the daily neighborhood machinations at a minimum. In addition, these parents may also enlist the help of their extended family and friends. According to Jarrett (1999), parents often try to expose their children to the more advantaged neighborhoods that their kin live in. For instance, they may seek out the more plentiful institutional resources that may be available in the areas that other family members and friends live in. In addition, sometimes they will even allow their children to move in with their kin in better neighborhoods in order to protect them from the neighborhoods in which they themselves live. Yet another effective technique that parents in disadvantaged areas use to lessen the impact of their neighborhoods on their children are in-home learning strategies. These parents recognize that their children are at an educational disadvantage compared © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 28 to their counterparts in more privileged neighborhoods. Therefore, they actively promote learning in their own home. For example, they may make a point of playing educational games with their children that reinforce math and reading skills. Additionally, they may ensure that books are available for their children to read at home by making frequent trips to libraries. Jarrett (1999) also describes how some parents who are not well educated employ this in-home learning strategy. While they themselves may not be capable of helping their children with schoolwork or teaching them new skills, these parents offer their children an encouraging home environment and stress the importance of education for their children’s future. They may, for example, praise their children for doing their homework or for earning good grades. In addition, they may constantly reinforce the importance of their children’s education by noting that their own lack of education has left them with limited job opportunities and limited economic success. While these parenting strategies are just a few of those that parents can use to help protect their children from disadvantaged and often dangerous neighborhoods, they have been shown to be used by many parents who manage to raise resilient children in spite of their neighborhood context. While neighborhood effects may exist, the diligent efforts of these parents, often employed at the expense of their own well-being, may serve to lessen the negative impact of neighborhoods on their children’s development. Therefore, the importance of families, and parents in particular, should not be ignored when studying how and why neighborhoods may affect the developmental outcomes and life chances of children and adolescents. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 29 IX. Conclusion While the above mentioned research indicates that there is empirical evidence that supports the notion that neighborhoods exert an influence over the developmental outcomes of children and adolescents in some way, the true extent of neighborhood effects remains unknown. Ginther, et al. (2000), who reviewed the literature with an eye toward determining the magnitude of neighborhood effects, concluded that estimated effects are inconsistent across the studies. Furthermore, they claimed that “The conclusions reached by the authors vary as widely as the estimates, from a ‘rather circumscribed role’ for neighborhood variables to ‘substantial’ effects” (p. 607). One reason for this may be the methodological problems that surround neighborhood research. For example, researchers have not even been able to come up with an accurate way to define particular neighborhoods under study. Census tracts, zip codes, and school districts often serve as proxies for neighborhoods for lack of better, more precise measures. In addition, as Ellen and Turner (1997) point out, “it is difficult to separate the effects of neighborhood environment from individual or family characteristics, especially characteristics that are difficult to measure and observe” (p. 843). While more research is needed to get a better grip on exactly how and to what extent neighborhoods impact on children, results from the recent research do suggest that neighborhoods do, in some way, shape, or form, impact on the developmental outcomes and life chances of the children and adolescents who grow up in them. While families, © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 30 schools and other individual-level factors cannot and should not be discounted when it comes to studying child development, neither should neighborhood context be ignored. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 31 Appendix In order to have a better sense of the research presented in this paper, four maps of Erie County and Buffalo, New York are included. Each represents to what extent the various census tracts in the city and county possess the variables that are most commonly used throughout neighborhood effects research to measure neighborhood disadvantage. As census tracts are often used as proxies for neighborhoods, the boundaries of each census tract in the city and county are included. Graduated coloration is used to depict the level of concentrated poverty, racial and ethnic segregation, unemployment, and single female headed households in each tract. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 32 © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 33 © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 34 © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 35 © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 36 References Aaronson, Daniel. 1998. “Using Sibling Data to Estimate the Impact of Neighborhoods On Children’s Educational Outcomes.” Journal of Human Resources 33:915945. Ainsworth, James W. 2002. “Why Does it Take a Village? The Mediation of Neighborhood Effects on Educational Achievement.” Social Forces 81:117-152. Anderson, Elijah. 1989. “Sex Codes and Family Life Among Inner-City Youths.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 501:59-78. Baumer, Eric P. and Scott J. South. 2001. “Community Effects on Youth Sexual Activity.” Journal of Marriage and Family 63:540-554. Brewster, Karin L. 1994. “Race Differences in Sexual Activity Among Adolescent Women: The Role of Neighborhood Characteristics.” American Sociological Review 59:408-424. Brewster, Karin L., John O. G. Billy, and William R. Grady. 1993. “Social Context and Adolescent Behavior: The Impact of Community on the Transition to Sexual Activity.” Social Forces 71:713-740. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 37 Brody, Gene H., et al. 2001. “The Influence of Neighborhood Disadvantage, Collective Socialization and Parenting on African American Children’s Affiliation with Deviant Peers.” Child Development 72:1231-1256. Brooks-Gunn, Jeanne, et al. 1993. “Do Neighborhoods Influence Child and Adolescent Development?” American Journal of Sociology 99:353-395. Chase-Lansdale, P. Lindsay, et al. 1997. “Neighborhood and Family Influences on the Intellectual and Behavioral Competence of Preschool And Early School-Age Children.” In Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Greg J. Duncan, and J. Lawrence Aber (Eds.). Neighborhood Poverty. Volume I. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Crane, Jonathan. 1991. “The Epidemic Theory of Ghettos and Neighborhood Effects on Dropping Out and Teenage Childbearing.” American Journal of Sociology 96: 1126-1159. Duncan, Greg J. 1994. “Families and Neighbors as Sources of Disadvantage in the Schooling Decisions of White and Black Adolescents.” American Journal of Education 103:20-53. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 38 Duncan, Greg J., Johanne Boisjoly, and Kathleen Mullen Harris. 2001. “Sibling, Peer, Neighbor, and Schoolmate Correlations as Indicators of the Importance of Context for Adolescent Development.” Demography 38:437-447. Ellen, Ingrid Gould and Margery Austin Turner. 1997. “Does Neighborhood Matter? Assessing Recent Evidence.” Housing Policy Debate 8:833-866. Elliott, Delbert S., et al. 1996. “The Effects of Neighborhood Disadvantage on Adolescent Development.” The Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 33:389-410. Ennett, Susan T., et al. 1997. “School and Neighborhood Characteristics Associated With School Rates of Alcohol, Cigarette, and Marijuana Use.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38:55-71. Ensminger, Margaret E., Rebecca P. Lamkin, and Nora Jacobson. 1996. “School Leaving: A Longitudinal Perspective Including Neighborhood Effects.” Child Development 67:2400-2416. Entwisle, Doris R., Karl L. Alexander, and Linda S. Olson. 1994. “The Gender Gap in Math: Its Possible Origins in Neighborhood Effects.” American Sociological Review 59:822-838. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 39 Furstenberg, F. 1993. “How Families Manage Risk and Opportunity in Dangerous Neighborhoods.” Pp. 231-258 in Sociology and the Public Agenda, edited by W.J. Wilson. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Garner, Catherine L. and Stephen W. Raudenbush. 1991. “Neighborhood Effects On Educational Attainment.” Sociology of Education 64:251-262. Ginther, Donna, Robert Haveman, and Barbara Wolfe. 2000. “Neighborhood Attributes as Determinants of Children’s Outcomes: How Robust Are the Relationships?” The Journal of Human Resources 35:603-642. Gonzales, Nancy A., et al. 1996. “Family, Peer, and Neighborhood Influences on Academic Achievement among African-American Adolescents: One-Year Prospective Effects.” American Journal of Community Psychology 24:365-385. Halpern-Felsher, Bonnie L, et al. 1997. “Neighborhood and Family Factors Predicting Educational Risk and Attainment in African American and White Adolescents.” In Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Greg J. Duncan, and J. Lawrence Aber (Eds.). Neighborhood Poverty. Volume I. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Hogan, Dennis P. and Evelyn M. Kitagawa. 1985. “The Impact of Social Status, Family Structure, and Neighborhood on the Fertility of Black Adolescents.” American Journal of Sociology 90:825-855. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 40 Jarrett, Robin L. 1999. “Successful Parenting in High-Risk Neighborhoods.” The Future of Children, 9:45-54. Jencks, Christopher and Susan E. Mayer. 1990. “The Social Consequences of Growing Up in a Poor Neighborhood.” In Laurence E. Lynn, Jr., and Michael G.H. McGeary (Eds.). Inner-City Poverty in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Kasarda, John D. 1993. “Inner-city Concentrated Poverty and Neighborhood Distress: 1970-1990.” Housing Policy Debate4:253-302. Kohen, Dafna E., et al. 2002. “Neighborhood Income and Physical and Social Disorder In Canada: Associations with Young Children’s Competencies.” Child Development 73:1844-1860. Kowaleski-Jones, Lori. 2000. “Staying Out of Trouble: Community Resources and Problem Behavior among High-Risk Adolescents.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 62:449-464. Ku, Leighton, Freya L. Sonenstein, and Joseph H. Pleck 1993. “Neighborhood, Family, and Work: Influences on the Premarital Behaviors of Adolescent Males.” Social Forces 72:479-503. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 41 Leventhal, Tama, and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn. 2000. “The Neighborhoods They Live in: The Effects of Neighborhood Residence on Child and Adolescent Outcomes.” Psychological Bulletin 126:309-337. Ludwig, J., Greg J. Duncan, and P. Hirschfield. 1998. “Urban Poverty and Juvenile Crime: Evidence from a Randomized Housing-Mobility Experiment.” In Rosenbaum, Emily, and Laura E. Harris. 2001. “Low-Income Families in their New Neighborhoods: The Short-Term Effects of Moving from Chicago’s Public Housing.” Journal of Family Issues 22:183-210. McCulloch, Andrew and Heather E. Joshi. 2001. “Neighbourhood and Family Influences on the Cognitive Ability of Children in the British National Child Development Study.” Social Science & Medicine 53:579-591. Newman, Katherine S. 1999. No Shame in My Game: The Working Poor and the Inner City. New York: Vintage Books & Russell Sage Foundation. Quane, James M. and Bruce H, Rankin. 1998. “Neighborhood Poverty, Family Characteristics, and Commitment to Mainstream Goals: The Case of African American Adolescents in the Inner City.” Journal of Family Issues 19:769-795. Rosenbaum, James E. 1995. “Changing the Geography of Opportunity by Expanding Residential Choice: Lessons from the Gautreaux Program.” Housing Policy © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 42 Debate 6:231-269. Rosenbaum, Emily and Laura E. Harris. 2001. “Low-income Families in Their New Neighborhoods: The Short-term Effects of Moving from Chicago’s Public Housing.” Journal of Family Issues 55:183-210. Sampson, Robert J. 1997. “Collective Regulation of Adolescent Misbehavior: Validation Results from Eighty Chicago Neighborhoods.” Journal of Adolescent Research 12:227-244. Sampson, Robert J., and W. Byron Groves. 1989. “Community Structure and Crime: Testing Social-Disorganization Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 94:774780. Sampson, Robert J., Jeffrey D. Morenoff, and Thomas Gannon-Rowley. 2002. “Assessing “Neighborhood Effects”: Social Processes and New Directions in Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 28:443-478. Seccombe, Karen. 2000. “Families in Poverty in the 1990s: Trends, Causes, Consequences, and Lessons Learned.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 62: 1094-1113. Shaw, Clifford R., and Henry D. McKay. 1942. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation Children and Neighborhood Context 43 Small, Mario Luis and Katherine Newman. 2001. “Urban Poverty after The Truly Disadvantaged: The Rediscovery of the Family, the Neighborhood, and Culture.” Annual Review of Sociology 27:23-45. Solon, Gary, Marianne E. Page, and Greg J. Duncan. 2000. “Correlations Between Neighboring Children in Their Subsequent Educational Attainment.” The Review Of Economics and Statistics 82:383-392. South, Scott J. and Eric P. Baumer. 2000. “Deciphering Community and Race Effects On Adolescent Premarital Childbearing.” Social Forces 78:1379-1407. Teitler, Julien O. and Christopher C. Weiss. 2000. “Effects of Neighborhood and School Environments on Transitions to First Sexual Intercourse.” Sociology of Education 73:112-132. Vartanian, Thomas P. 1999. “Adolescent Neighborhood Effects on Labor Market and Economic Outcomes.” Social Service Review 73:142-173. Wilson, William Julius. 1987. The Truly Disadvantaged. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. © 2003 CDHS College Relations Group Buffalo State College/SUNY at Buffalo Research Foundation