Property Briefs

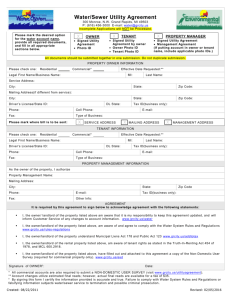

advertisement