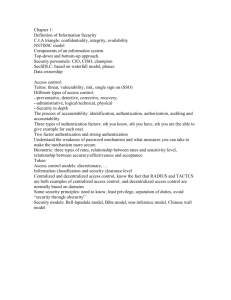

5.0 What is Identification Authentication and Authorization?

advertisement