Form 61 - The Mail Archive

Essenberg v Shields

14 December 2000

Submission by Martin Essenberg

To the Nanango Magistrates Court

1.

My name is Martin Essenberg and I am appearing for myself.

2.

Because I am unfamiliar with advocacy I respectfully ask the court that I may read from prepared notes for the purposes of oral argument.

3.

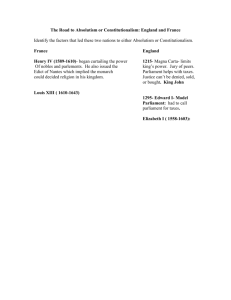

In the hysteria that followed the Port Arthur massacre, politicians passed gun laws all over Australia. I honestly believe these laws are not within the legal competence of the parliaments that passed them. They offend a number of laws that were in place when the referendum was passed in 1899. The repeal of those laws was outside the competence of Parliament then- and I honestly believe they still are.

4.

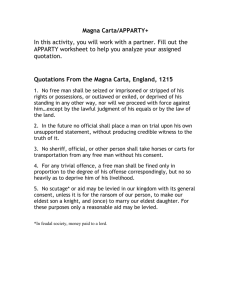

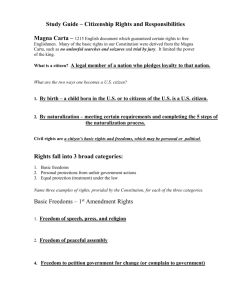

As an Australian I am a subject of the Queen, and am entitled to the protection of the Crown and the charters such as Magna Carta, which guarantees the inalienable right of trial by jury.

5.

In Essenberg v Queen in the High Court Judge McHugh states that

“Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights are not documents binding on Australian legislatures in the way that the Constitution is binding on them. Any legislature acting within the powers allotted to it by the Constitution can legislate in disregard of Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights. At the highest, those two documents express a political ideal, but they do not legally bind the legislatures of this country or, for that matter, the

United Kingdom. Nor do they limit the powers of the legislatures of Australia or the

United Kingdom.”

6.

This judgement is contradictory to many High Court and Queensland Supreme

Court Judgements given previously where the Common Law, The Magna Carta and the Bill of rights have been introduced as precedents.

7.

A precedent is defined as a judgement or decision of a court of law cited as an authority for deciding a similar set of facts; a case which serves as an authority for the legal principle embodied in its decision.

8.

The High Court precedent of PLENTY - v - Dillon (1991) 171 CLR 635 F.C.

91/004 The case traces the history of the law and supporting rulings (precedent) back to the Magna Carta in 1215 A.D.

9.

The judgement of Lord Camden in Entick v Carrington (1765) which was introduced into Plenty v Dillon by the High Court and therefore became a case which was used and may continue to be used by Australian Courts as a precedent.

10.

In Stanbridge v The Premier of Queensland [1995] QSC 201 (25 August 1995)

Mackenzie J said “In the recent Court of Appeal decision of Criminal Justice

Commission v. Nationwide News Pty Ltd (1994) 74 A. Crim. R. 569, 584 Davies

J.A. said:- "The purpose of article 9 was in my view to ensure that what was said

and done in the performance of the functions of Parliament .... was free of sanction by a Court. Otherwise the business of Parliament could not be freely conducted."

11.

In Pepper (Inspector of Taxes) v. Hart (1993) AC 593, 638 Lord Browne-Wilkinson said:-"... the plain meaning of article 9 ... was to ensure that members of

Parliament were not subjected to any penalty, civil or criminal, for what they said and were able ... to discuss what they ... chose to have discussed."

12.

Freedom to discuss is hardly Parliamentary Supremacy. How in Stanbridge v the

Premier could Wayne Goss claim Parliamentary Privilege if the Bill of Rights is no longer valid?

13.

In the matter of Brofo v Western Australia (1990) 93 ALR 207, there was much discussion of the Acts which bind the Crown.

14.

Holding v Jennings (1979) VLR, records that the Victorian Supreme Court upheld

Article 9 of the Bill of Rights of 1688

15.

In the High Court matter of Television Company v ALP - with regard to the ban on political speeches just before an election the High Court upheld the common law right of free speech.

16.

In the USA in EMERSON v UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Judge Cummings

SR goes into some detail on the history of the Right to bear arms, the Bill of Rights and the Rights of the American colonists.

17.

The Bill of Rights and other Imperial Charters were introduced to Australia when it was a colony.

18.

As we were British subjects at that time:-

19.

By Royal patent from Queen Elizabeth I in 1578, Sir Humphrey Gilbert was to take possession of ‘...lands .... all who settled there should have and enjoy all the privileges of free denizens and natives of England’ [viz. equals British subject, today];*pg 9

20.

By Royal patent from King James I in 1606, Walter Raleigh received thus ‘ all

British subjects who shall go and inhabit within the said colony and plantation, and their children and posterity, which shall happen to be born within the limits thereof, shall have and enjoy all the liberties, franchises, and immunities thereof, to all intents and purposes, as if they had been abiding and born within their own realms of England or any other of our other dominions.’

* p 11. Annotated ‘notes’. Further [see pp 90-1, The LEGISLATIVE POWERS of the Commonwealth & the States of Australia: by Sir John Quick 1919]

21.

The Bill of Rights, the Magna Carta and many other Imperial acts were further confirmed by the Imperial Acts Application Act 1984 as being valid in Queensland.

22.

The Imperial Acts Application Act 1984 is a Constitutional enactment and as such can only be altered by a referendum under the Queensland Constitution Act 1867.

Courts cannot find as fact that a Statute is not a law. The active Magna Carta

section is Chapter 29 of the Act of 1297. The Imperial Acts application Act 1984 declares it to be so. It is res judicata.

23.

Denver Beanland, when he was Attorney General confirmed that the Bill of Rights was still applicable in Queensland. The current Attorney General Matt Foley when asked by Dorothy Pratt MLA in a Question on Notice (attached) seems to have abdicated his responsibilities to the High Court.

24.

In 1915, the High Court of Australia, through the Chief Justice [Sir Samuel Griffith] confirmed the common law within the Commonwealth of Australia: -

“It is clear law that in the case of British Colonies acquired by settlement, the colonies carry their laws with them so far as they are applicable to the altered conditions. In the case of the Eastern colonies of Australia this general rule was supplemented by the

Act 9 Geo. IV.[1828] c. 83. The laws so brought to Australia undoubtedly included the common law relating to the rights and prerogatives of the Sovereign in His capacity as head of the Realm and the protection of His officers in enforcing them, including so much of the common law as imposed loss of life or liberty for infraction of it. When the several Australian colonies were erected this law was not abrogated, but continued in force as law of the respective colonies applicable to the

Sovereign as their head. It did not, however, become disintegrated into six separate codes of law, although it became part of an identical law applicable to six separate political entities. The same principles apply to the laws of the United Kingdom of general application such as the Statute of Treasons. In so far as any part of this law was repealed in any Colony, it, no doubt, ceased to have affect in that Colony, but in all other respects it continued as before. When in 1901 the Australian

Commonwealth was formed, this law continued to be the law applicable to the rights and prerogatives of the Sovereign as heads of the States as before, subject to any such local repeal. But, so far as regards the Sovereign as head of the

Commonwealth, the current which had been temporally diverted into six parallel streams coalesced, and in that capacity he succeeded as head of the Commonwealth to the rights he had had as head of the Colonies. I entertain no doubt that it was an offence at common law to conspire to defraud the King as head of the Realm, that on settlement of Australia that part of the common law became part of the law of

Australia, that on the establishment of the Commonwealth the same law made it an offence to conspire to defraud the Sovereign as head of the Commonwealth.

.................”

per GRIFFITH C.J., 20 C.L.R., 435-6. Also endorsed by ISAACS J.

445-6 and HIGGINS J. 454

25.

From the above Royal patents, the reference to people being British subjects in any

Statute means that it applies ‘throughout the Empire’.

In CONCLUSION

26.

As a Colony we inherited the Common law including the Bill of Rights and Magna

Carta

27.

The Imperial Acts Application Act 1984 reconfirmed that they are still valid enactments

28.

Many parts of Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights and the Common laws have been introduced by various Courts as precedents and can thus be used as an authority for the legal principle embodied in its decision.

CLAIM OF RIGHT for a Trial by Jury

29.

I have an honest claim of right (10.5) under the Criminal Code Act 1899 to rely upon the Criminal Code, section 92, to say that I do not have to submit to the

Jurisdiction of a magistrate in this matter, but must be tried by Jury. I submit my claim of right is reasonable, based as it is upon the Imperial Application Act 1984,

(5.2) Schedule 1 (1297) 25 Edward 1 ch 29, and (1688) 11 William and Mary Bill of Rights Sess 2 ch 2 Bill of Rights (13.1).

30.

In Walden V Hensler (1987) 163 COMMONWEALTH LAW REPORTS 561 the

High Court appears to uphold Section 22 for the benefit of Mr Walden. In 1999 in

Yanner V Eaton (1999) HCC 53 (7 th

Oct 1999) the High Court declared the law again, and while not mentioning section 22, Criminal Code have upheld a

Magistrate’s right to recognise an honest claim of right.

31.

In the case of Yanner , the claim of right arises out of the Native Title Act. Mine arises under the Constitution, (9.1) and the International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights, and the imperial Acts Application Act 1984, schedule 1 (1297) 25

Edward ch 29 (5.2). My claim of right is to be not tried by a public servant, appointed by the Governor, but by a Jury of my peers as I am supposed to be guaranteed, by the Imperial Acts Application Act 1984, schedule 1 (1297) 25

Edward ch 29 (5.2).

32.

(The High Court of Australia by majority, in Yanner V Eaton, upheld the magistrate’s recognition, at Mt Isa, that the Commonwealth could legislate to recognize individual sovereignty in an Aboriginal person.

33.

The High Court of Australia, by upholding the right of the delegates of the people of Australia to grant sovereign immunity, to one class of people, must now extend their decision. You must now extend that same privilege to each and every citizen of this democracy. The Anti Discrimination Act 1991(Q) and International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights binds the court, individually and collectively to apply equality to all. Section 13 Crimes Act 1914, is an equally certain statement of sovereignty, as the Statute which was relied upon by Mr Yanner.

34.

The Anti Discrimination Act 1991 (Q) confirms, in its long title, that the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights is domestic law

35.

In Paragraph 63, Justice Gummow chronicles where Mr Yanner made his honest claim of right to the Magistrate. The Magistrate accepted the honest claim of right as a defence and discharged Mr Yanner. This is chronicled in paragraph 64. In my case you should obey section 92 Criminal Code and not make an order prejudicial to me. Until the question of fact of whether the Weapons Act 1990 discriminates

(15.1) against me is decided by a jury unless I consent.

36.

There can be no doubt that an equity court was required to sit with a judge and jury in Queensland at the formation of the Commonwealth. There can be no doubt that

Section 118 Constitution gives that law full faith and credit throughout the

Commonwealth. There can be no doubt that if there is a conflict between the law and equity, equity must prevail.

37.

By the Judicature Acts 1876(Q) the functions in equity were vested in a court with a jury, not in a judge. The collective conscience of 12 jury persons was seen as equal to the collective conscience of the Church and Archbishop of Canterbury

38.

The evidence that juries were the norm in trials at common law, and compulsory, in

NSW in 1900, is contained in the Volume XXI NSWR 1 [1900.]

39.

A magistrate is unable to sit without a jury without offending the Magna Carta unless the accused grants him jurisdiction.

40.

The consent to be tried summarily must be clear and unequivocal and a failure to carry out the procedures for obtaining the consent will deprive the court of jurisdiction to determine the matter summarily (Halsbury’s laws of Australia (para

130-13460). This provision is to prevent corruption and the usurpation of the role of the citizen in self-government, and prevent the oppression of minorities by majorities.

41.

When a judge sits alone, without consent, he is an administrative officer, not a judicial officer. He is a justice, not a judge, until he either obtains consent to act as a judge by all parties, or empanels a jury, to give the state power to make orders prejudicial to the sovereign members of that state. Judges may, however give administrative directions to enable the court to be created and brought into existence. It is not a court, until it either has consent to jurisdiction, or empanels a jury of 12 sovereign electors to perform the judicial function of finding fact for the court

42.

The difficulty that Australians are facing today is that the Governments of the

Commonwealth and of the States have meddled with the legal system, so that no

Court now sits in equity, with criminal and civil jurisdiction combined, or has the benefit of the combined consciences of 12 average Australians of the same peer group as those who are before the court.

MAY

43.

Summary proceedings are consent proceedings in all Courts and unless the consent of the defendant is obtained, it is the law that a jury be empanelled

44.

Summary offences are only offences that may be prosecuted without a jury. The operative word being "may" . If one is asked for the defendant has an absolute right to get the jury for a trial and the findings of the jury bind the sovereign. That ensures fairness and impartiality.

45.

The Weapons Act, section 137, part 1, has the word "may" in it. "May" means that it is not compulsory for the offence I allegedly committed to be tried in a summary manner. It means that if I ask for a jury trial, that I be entitled to be tried on indictment.

46.

WARD v. WILLIAMS (1955) 92 CLR 496 at 8.

In considering the correctness of this interpretation it is necessary to bear steadily in

mind that it is the real intention of the legislature that must be ascertained and that in ascertaining it you begin with the prima facie presumption that permissive or facultative expressions operate according to their ordinary natural meaning. "

47.

“The authorities clearly indicate that it lies on those who assert that the word 'may' has a compulsory meaning to show, as a matter of construction of the Act, taken as a whole, that the word was intended to have such a meaning" - per Cussen J.: Re

Gleeson (1907) VLR 368, at p 373.

48.

"The meaning of such words is the same, whether there is or is not a duty or obligation to use the power which they confer. They are potential, and never (in themselves) significant of any obligation. The question whether a Judge, or a public officer, to whom a power is given by such words, is bound to use it upon any particular occasion, or in any particular manner, must be solved from the context, from the particular provisions, or from the general scope and objects, of the enactment conferring the power" - per Lord Selborne : Julius v. Bishop of Oxford

(1880) LR 5 AC 214, at p 235.

49.

One situation in which the conclusion is justified that a duty to exercise the power or authority falls upon the officer on whom it is conferred, is described by Lord

Cairns in his speech in the same case. His Lordship spoke of certain cases and said of them: "They appear to decide Nothing more than this: that where a power is deposited with a public officer of the purposes of being used for the benefit of persons who are specifically pointed out and with regard to whom a definition supplied by the legislature of the conditions upon which they are entitled to call for his exercise, that power ought to be exercised and the Court will require it to be exercised." Per Lord Selborne: Julius v. Bishop of Oxford (1880) LR 5 AC 214, at p

235.

50.

If the legislature intended to have a Judge refuse a jury trial it would have clearly indicated its intention in the Weapons Act. A Judge can grant a jury trial and should not refuse a jury trial to grant a benefit to one litigant over another, particularly when the other litigant is a fellow public officer. In such a case "may" becomes

"must" , or the system is seen to be a servant of the Executive Government and not acting impartially. If the legislature intended that I not be entitled to a jury trial, it would have said, "must" , not "may" .

51.

The respondent's argument in the Kingaroy District Court (Essenberg v Carne) includes the word "may" . Section 161 of the Weapon's Act provides that, "A proceeding for an offence under this Act other than section 65 MAY be prosecuted in a summary way." The second argument of the Prosecution was section 19 of the

Justices Act, "Where an offence under any Act is not declared to be an indictable offence, the matter MAY be heard and determined by a Magistrates Court in a summary matter."

52.

Where does it say that trial by Jury is precluded in this case?

53.

"May" is a word of decided judicial import. If the discretion is not consented to, it is the duty of the Court to treat all offences with a possible penalty of over 3 months as indictable offences to avoid the stigma of corruption overhanging the Court. The

Criminal Code Section 204 obliges the magistrate to set the matter down on the request of any defendant for a jury trial, or offend section 200 Criminal Code.

Refusal of Public officer to perform duty .

PARLIAMENTARY SUPREMACY

54.

Between elections, Parliaments think they have an unfettered power to do whatever the controlling party decides should be done, and that they can ride rough shod over the people who delegate law making powers to them. Parliament believe they are supreme,

55.

The people of Queensland by referendum, decided in 1899, to continue the common law tradition we inherited from English colonists. They did not intend that once every three years we could review parliament.

56.

In Calder V Bull, Chase, J:

“I cannot subscribe to the omnipotence of a state legislature…. An act of the legislature, (for I cannot call it a law) contrary to the great first principles of the social compact cannot be considered a rightful exercise of legislative authority.

” 1798 3 Dallas 386

57.

The perception, apparently supported by our courts, that Parliament has absolute sovereignty from the English Bill of Rights Act 1689, is fundamentally flawed.

They omit "charters" which could never be impeached or invalidated and then brazenly claim their rights of absolute Parliamentary sovereignty from that same

Act. For without the Bill of Rights where is Parliamentary Privilege let alone

Supremacy?

58.

Many Sections of the Constitution entrench the power in the Monarch but Section 9,

Sub Section 61 States "The executive power of the Commonwealth is vested in the

Queen". No parliament anywhere can create a monarchy. It is the Monarch who creates the Parliament. So who is supreme?

59.

The Bill of Rights (1688) was a peace treaty that replaced the abdicated Monarch,

James II with William and Mary. It also confirmed the Common laws and Magna

Carta and corrected abuses that had been done by James II.

60.

Throughout the Bill of Rights, and the acts making up the 2 sessions of Parliament, including the oath of supremacy, the people acknowledge the monarch as the Head of state, having final say.

61.

Parliament was enacted into statute in a position of checks and balances to the

Royal prerogative but at no time was the royal prerogative stripped from the monarch

62.

If Parliament were supreme why is there a need to have the sovereign (Via the

Governor) give royal assent to legislation before it can become law? Because that is one of the checks and balances to protect people from tyranny.

63.

The Federal Parliament and the state Parliaments are not sovereign bodies. They are legislatures with limited powers. Any law they attempt to pass in excess of those powers is no law at all. It is void and entitled to no obedience.

64.

Any laws Parliament makes must be in accordance with the recognised principles of representative democracy, constitutional law and the rule of law

65.

" For the Parliament to develop or improve on a fundamental right is one thing. But to enact legislation which expressly removes an already existing fundamental right, and to have that enactment blindly upheld by a Court, is quite another”

66.

" If there is one thread which runs through the whole turbulent history of British constitutional development, it is the belief that we are the servants of fundamental constitutional rules which were there before us and will be there after we are gone.

From the days when the King’s subjects demanded respect for the laws of King

Edward the Confessor, through the centuries in which legendary superiority attached to such acts as Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, the Bill of Rights, the idea of our ancient rights and liberties has determined the form of our endlessly progressive/conservative constitutional change." (Allott, The Courts and Parliament

Who Whom? (1979) CLJ. at 114)

67.

If Parliament has the power to make a legally binding command, no matter what the subject matter of that command, then it is entirely possible that a direct conflict will arise between the duty to obey the law and the moral duty not to obey wicked laws.

This conundrum was solved in earlier times by the social contract. If the sovereign failed to protect the people in the enjoyment of their basic liberties, then it breached its’ contract with its’ subjects, and the oppressive

"law" could not be binding.

Reliance was placed on unchanging common law, or on the Magna Carta, a true convenant between the sovereign and the subject.

68.

The Australian Parliament claims its rights and privileges from the Bill of Rights

1689 (1 Will & Mary sess 2 c 2 1689) which demonstrated that the victors in the

Revolution had sought to protect, not to change, the fundamentals of the constitution. The framers of that document were simply declaring common law that already existed and would continue to exist.

69.

The Bill of Rights was preserving the supremacy of Parliament over any future

Monarch who might feel disposed to assert the opposite. Parliament is sovereign in that sense, not in the sense that it is incapable of doing wrong or that no one may question the validity of an Act of Parliament.

70.

Sir William Blackstone mentions the importance of the Bill of Rights and particularly clause 7:

“The fifth and last auxiliary right of the subject, that I shall at present mention, is that of having arms for their defense, suitable to their condition and degree and such as allowed by law. Which is also declared by the same statute [the Bill of

Rights] and it is indeed a public allowance under due restrictions, of the natural right of resistance and self-preservation, when the sanctions of society and the laws are found insufficient to restrain the violence of oppression.”

William Blackstone,

Commentaries on the Law of England (1765), Vol. 1, 144.

71.

Surely the framers of the Bill of Rights did not intend to enshrine parliamentary superiority in clause 9 and allow subsequent parliaments to eliminate the freedoms given to the people in clause 7 of the Bill of Rights and clause 29 of the Magna

Carta. After all the freedoms of Magna Carta preceded the existence of Parliament by several hundred years.

ENTRENCHMENT

72.

Entrenched Provisions are laws enacted that may not be repealed or amended, or the affect of which may not be altered, by Parliament unless it follows a special, additional procedure, such as approval by the majority of electors at referendum or approval by a two thirds majority in the Parliament. The entrenchment of a law reflects Parliaments intention to protect a law that it considers to be of special significance, by inhibiting a successor Parliament’s ability to amend the law through the normal law- making procedure.

73.

The entrenchment of a law usually occurs by a substantive provision (the entrenched provision) being subjected to another provision (the entrenching provision) which states that the substantive provision may not be repealed or affected without observance of the special additional procedure.

74.

To fully entrench a law, the entrenching provision must also subject itself to the same special procedural requirement before it can be amended (that is the entrenching procedure entrenches itself.) When this occurs, the substantive provision is said to be “doubly entrenched”

Legal, Constitutional and

Administrative Review Committee report no 13, April 99 on the Consolidation of the Queensland Constitution- sec 2.3

75.

Both the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights are doubly entrenched and may not be altered by any means

COMMON LAW

76.

The common law, which applies in Australia, is the common law of England as it existed in 1836, as it was translated into the colonies and as it has developed within this colony and state in the last 148 years.

77.

All Colonists had these rights from Britain and any subsequent Colonial legislation was only confirming what already existed.

78.

In the Boyer Lecture one (attached) Chief Justice Murray Gleeson on 19/11/00 said: “

The common law of Australia was based upon the common law of England.

We inherited it at the time of European settlement. The word ‘common’ was a reference to the rules that applied to all citizens, the laws all people had in common, as distinct from special rules and customs that applied to particular classes, such as members of the clergy, or in particular places

.”

79.

Dr. David Mitchell B.A. L.L.B. Ph.D L.L.M.) Said: “

We have not been taught at school what the Common Law is, or where it is derived from. I need to remind you

that when this country was settled, they brought with them a System of Law; a

System of Rights; and a System of Constitution. That system was based on the Ten

Commandments.

80.

Before it was joined into the United Kingdom the constitutional structure of

England was that there was a King, who was advised by a team of advisers who had come to be called Parliament; and there was a Court System. King Alfred decreed and declared that the responsibility of the Crown was to apply the Ten

Commandments to every question that came before them; they were to interpret the

Ten Commandments in the light of the whole of Scripture. So the people were to find their rights - that is to say, how the court would handle any issue - in the

Christian Scriptures.

81.

But what if a judge, who of course, in deciding his case would be declaring the word of God, and would be declaring God’s way for handling that particular issue -

- what if the judge was wrong, either because he was bribed, or drunk or simply he had misunderstood Scriptures? Here was a basic function of the King’s advisers.

82.

The basic function of the Parliament was to ensure the wrong court decisions did not become precedents; that is to say, that wrong court decisions were not binding for subsequent cases when they became before the courts. So the Parliament was to tell the King what was the proper interpretation of Scripture. Thus courts were subject to God’s Word: Parliament was subject to God’s Word: the King was subject to God’s Word. There were three parts of the Constitution: King; Courts; and Parliament (or Legislature); reflecting the concept of the holy trinity. So the

Constitution of England came into existence those many years ago, and was the

Constitution when Australia was settled.

83.

Over the years the constitutional basis was often neglected, rejected, or forgotten.

The Hon. John Howard has today, [July 1988] correctly drawn attention to Magna

Carta and our other basic constitutional documents. John Howard said “ Our basic rights have been defined over the centuries through acts of Parliaments, decisions of courts, the ancient Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights of the British Parliament and so forth. They are our basic rights ...”

84.

Our rights under the old Bills and Statutes are still with us and still live. We see from the above that: neither the courts of law, nor the parliament, nor the government as a whole, were originally there to ‘think up’ laws. They were there to uphold THE LAW.”

(Based from a transcript of an address given 1/ 7/88 @

Chapter House, Sydney NSW.)

85.

The common law was declared by the Criminal Code Act 1899 in Queensland, and

Section 92 of the Criminal Code, gives effect to the Magna Carta C 29. It says,

Abuse of Office, Any person being employed in the public service does or directs to be done, in abuse of the authority of the person's office, any arbitrary act prejudicial to the rights of another is guilty of a misdemeanour, and is liable to imprisonment for 2 years.

86.

The case of R v Lord Chancellor ex parte Witham implies that Acts of Parliament cannot repeal common law and our rights have fallen into abeyance through lack of a suitable challenge.

Constitutional Argument

87.

I contend that the Weapons act 1990 of Queensland, under which I was charged under section 50 cannot stand. I would raise various constitutional points in relation to the invalidity attracting Federal Judicial power by the defence raised.

88.

In Felton V Mulligan it was held that “once federal jurisdiction is attracted, even in a point raised in defence the jurisdiction exercised throughout the case will remain a Federal jurisdiction”

(Felton v Mulligan (1971) 124 CLR 367 at 373, 412, 413)

The Federal nature of the matter being apparent from the claim itself. (Felton V

Mulligan pg 22)

89.

I contend that Federal jurisdiction having been thus invoked the substance of my claim as to conflict of law should have been examined, and a summary trial not proceeded with until the validity of the act in question was determined.

90.

My defence in previous trials has been consistently founded on the question of

Constitutionality.

91.

All persons are equal before the law and if one person who is equal to another asserts that the Constitution applies and another asserts that it does not, then a justiciable dispute arises within the original jurisdiction of the High Court of

Australia by reference to Section 30 Judiciary Act 1903, and it is a dispute involving the contract between the State of Queensland and the Commonwealth of

Australia made for the benefit of the Australian citizenry. It is a basic right of all citizens to a jury trial in such a dispute.

92.

The State of Queensland is in this matter, acting de facto for the Federal government, and as such must exercise the Judicial power of the Commonwealth in accordance with the Constitution and try the matter with a Judge only by reference to section 79 Constitution, which says: The Federal jurisdiction of any Court may be exercised by such number of judges as the parliament prescribes.

93.

If the defendant requires a jury, the Court may not be constituted without a jury unless the defendant consents by reference to Sections 51 and 259 Supreme Court

Act 1995. This Act is of full force in Federal jurisdiction by reference to section 118 of the Constitution, which says: Full faith and credit shall be given, throughout the

Commonwealth, to the laws, the public Acts and records and the judicial proceedings of every State.

94.

A magistrate is not a judge and as such cannot exercise a federal judicial function at all.

95.

I further contend that given the criminal tenor of the act under which I was charged,

I should be afforded a Jury Trial in that, given the compaginated arrangements between the Federal and State Governments under covering Clause 5 of the

Constitution, the Queensland Government is restrained from passing legislation conferring jurisdiction upon a state court incompatible with the exercise of Federal

Judicial power. The argument of incompatibility has its foundation in the judicial power of the Commonwealth as identified by Chapter III of the Constitution, determined at length in Kable V the Director of Public Prosecutions of NSW FC

96/027. The majority decision upon which I rely Attached).

96.

In the case of Brown v The Queen the judges in the High Court emphasise the important role that trial by jury has in the administration of justice. On page 179

Chief Justice Gibbs said:

“The requirement that there should be trial by jury was not merely arbitrary and pointless. It must be inferred that the purpose of the section must be to protect the accused -- in other words, to provide the accused with a "safeguard against the corrupt or over-zealous prosecutor and against the compliant, biased, or eccentric judge "

97.

He goes on to say: “ the jury is a bulwark of liberty, a protection against tyranny and arbitrary oppression, and an important means of securing a fair and impartial trial. It is true that the jury system is thought to have collateral advantages (eg., it involves ordinary members of the public in the judicial process and may make some decisions more acceptable to the public)”

98.

This is a common theme in the High Court.

99.

In KINGSWELL v. THE QUEEN (1985) 159 CLR 264 Constitutional Law (Cth) -

Criminal Law (Cth)

“Regardless of whether one traces the common law institution of trial by jury to Roman, Saxon, Frankish or Norman origins, the underlying notion of judgment by one's equals under the law was traditionally seen as established in English criminal law, for those who had the power to be heard, at least by 1215 when the Charter of that year provided, among other things, that no man should be arrested, imprisoned, banished or deprived of life otherwise than by the lawful judgment of his equals ("per legale judicium parium suorum") or by the law of the land. Modern scholarship would indicate that much of the traditional identification of trial by jury with Magna Carta was erroneous. It is, however, clear enough that the right to trial by jury in criminal matters was, by the fourteenth century, seen in England as an "ancient" right. In the centuries that followed, there was consistent reiteration, by those who developed, pronounced, recorded and systematised the common law of England, of the fundamental importance of trial by jury to the liberty of the subject under the rule of law (see, eg. Co. Inst., Part II,

45ff.; Black. Comm. (1st Ed., 1966 rep.), Book III, pp.379-381, Book IV, pp 342-

344, and, generally, Singer v. United States (1965) 380 US 24, at p27 (13 Law Ed

2d 630, at p 633); Mr. Justice Evatt, "The Jury System in Australia", Australian

Law Journal, vol. 10 (1936), Supplement, 49, at pp.66-67, 72).

100.

When British settlements were established in other parts of the world, trial by jury in criminal matters was claimed as a "birthright and inheritance" under the common law and as an institution to be established and safeguarded to the extent that local circumstances would permit” (cf. the passage from Story's Commentaries on the Constitution quoted in Patton v. United States (1930) 281 US 276, at p 297

(74 Law Ed 854, at p 862); Kent's Commentaries, Lecture 24, pp 1-6; Rutland, The

Birth of the Bill of Rights, 1776-1791 (1983), p.19; United States ex rel. Toth v.

Quarles (1955) 350 US 11, at pp 16-17, n.9 (100 Law Ed 8, at p 14, n.9), and, as to

Australia, J.M. Bennett, "The Establishment of Jury Trial in New South Wales",

Sydney Law Review, vol. 3 (1959-1961), 463).-

MAGNA CARTA

101.

The Magna Carta was a peace treaty signed in 1215 to end a civil war in Britain. It confirmed the Common law rights of the people and corrected abuses of law that had been done by King John. It concerns the limits and responsibilities of

Government and the legal rights of free citizens.

102.

Although the 1215 Magna Carta treaty was reneged on by King John it was reaffirmed by his son on Johns death and has been re-affirmed in various ways some 38 times since it was first enacted.

103.

Magna Carta was never a statute it was a peace treaty and not subject to legislative amendment. The Queen confirmed that it was a peace treaty in 1997.

104.

Ch 29 Magna Carta 1225 (2)

“No man shall be disseised, that is, put out of seison, or disposed of his freehold (that is) lands, or livelihood, or of his liberties, or freecustoms, that is, of such franchise, and freedoms, and free-customs, as belong to him by his free birthright, unless it be by the Lawful Judgement, that is, verdict of his equals, (that is, of men of his own condition) or by the law of the land, (that is, to speak at once for all, that is, the universal common law), by the due courts, and process of law”.

105.

Magna Carta is predicated upon the auto-cephalous authority of the people at natural law, and if it did not exist in script, would, notwithstanding, continue to have a presence by virtue of the generic existence of the inhabitants of the British

Isles, and their descendents, and is of precatory form, spanning generations, by virtue of self-genesis, as indeed, is all customary law.

106.

The Right to a Jury trial (and also private ownership of arms for defence) was entrenched in the Bill of Rights as a re-inforcement of the

“Independence of the

Jury”

, through the use of the Universal common law based upon the Holy

Scriptures, bought about by Williams Penn’s case in 1670.

107.

There is the choice, therefore, between the judgment of one's peers OR by the law of the land. And the law of the land does not just mean enacted statute law. It involves the high principles of the rule of law, due process of law, constitutional law, the rules of natural justice and the principle of ultra vires. (Beyond the power).

Bill of Rights

108.

The 2 Sessions of Parliament assented to under the one date 13 th

February 1688, are inseparable and indissoluble, re-establishing the throne of Great Britain, allowed

William and Mary to ascend to the Throne of Great Britain. It is under this, Queen

Elizabeth II obtains her authority and head of power to sit upon the throne of the

UK of Great Britain. It is established forever more as a blood covenant with all the people of the realm.

109.

The Monarch and the Parliament of the United Kingdom and Great Britain are under the subjection of all the ancient religion, law, rights and liberties of the realm based upon the Holy Scriptures.

110.

S1. 1 W & M, 1688, Session 1 settled the Oaths and Declarations to be taken, not only by William and Mary but also, by each and every successor of the Throne of the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

111.

Session 2 declared and enacted the Rights and Liberties of ALL the Subjects and settled the succession of the Throne, before William and Mary were declared King and Queen of the Realm and could ascend the Throne.

112.

The Throne of England was ONLY offered to William and Mary on the strict condition that they upheld the Ancient Laws and Customs of the Realm, these being declared in S.2 of the Parliament 1688.

113.

The Chapters of both Sessions of Parliament (1688) cannot be separated, repealed, annulled or amended, because ALL are conditional to the offering and acceptance of the Throne of the United Kingdom.

114.

Para iv, Cap VI, S. 1, 1 W & M, (1688) enacted the said Coronation Oath SHALL be in like manner administered to EVERY King or Queen who shall succeed to the

Imperial Throne of the Realm.

115.

Not only does the Monarch swear an oath, but all members of Parliament, all persons employed by the Monarch including Judges, court officials, agents, and advisors etc, were and are forevermore required to swear the said oaths also, to uphold and be under the subjection of all the Ancient Religion, Law, Rights and

Liberties of the Realm based upon the Holy Scriptures.

116.

Throughout the Bill of Rights and the statutes making up the two sessions of

Parliament (1688), the people acknowledge the Monarch as the Protector of the people, having the final say, due to a compact between God and ALL the people, for, as Coke’s exposition of Ch 1 of the Magna Carta has shown: Quod datum est ecclesia, datum est Dea”. “

At law, when anything is granted to God, it is deemed in law to be God’s…..”

No supremacy was given to Parliament, -NOR COULD IT

BE.

117.

S.2, 1 W&M, (1688) Cap. II, para VII declared William and Mary, King and

Queen; “and the said Lords spiritual and temporal, and commons, seriously considering how it has pleased Almighty God, in his marvelous providence, and merciful goodness to this nation, to provide and preserve their said Majesties Royal

Persons most happily to reign over us, upon the Throne of their ancestors,…. And do hereby recognise, acknowledge and declare, that King James II having abdicated the government, and their Majesties having accepted the Crown and

Royal Dignity as aforesaid, their said majesties did become were, are, and of right ought to be, by the laws of this realm, our sovereign lord and lady, King and Queen of England, France and Ireland, and the dominions thereunto belonging, in and to whose princely persons, the royal state, crown, and dignity of the said realm, with

all honours, styles, titles, regalities, prerogatives, powers, jurisdictions and authorities to the same belonging and appertaining, are most fully, rightfully and

ENTIRELY invested and incorporated, UNITED and ANNEXED”.

118.

This clearly declares the Monarch as having supreme power NOT parliament. The

Ancient Laws, Rights and Liberties under the Holy Scriptures were entrenched so that no one, including the Monarch or the Parliament, could abrogate the Ancient

Laws and Customs of the people.

119.

S.2, 1 W&M, (1688) Ch. II,

“and they do claim, demand, and insist upon all and singular the premisses, as their undoubted rights and liberties; and that no declarations, judgements, doings and proceedings, to the prejudice of the people in any of the said premisses ought in any wise to be drawn hereafter into consequence or example”.

120.

SS.1&2,1 W&M, (1688)

“and ALL the enactments thereto belonging, including the

Coronation Oath, the Bill of Rights, Oaths of Supremacy and Allegiance, forms one interdependent WRITTEN CONTRACT sealed between the Sovereign Monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and ALL the people of the United Kingdom, and the dominions thereto belonging, FOR ALL TIME TO COME with all the

Rights and Liberties asserted and claimed in the declaration enshrined forevermore”.

121.

No dispensation was allowed by either party (the Monarch and the People) to the contract. None were passed by that Parliament. The subject’s liberties were and are to be allowed in all times to come.

122.

No Member of Parliament could or can ever vote for or purport to enact any law in derogation of Her Majesty’s Coronation Oath or in derogation of the Sovereignty of the Queen - in – Parliament at Westminster.

123.

The Sovereign Queen - in – Parliament at Westminster. Her Majesty, Queen

Elizabeth II is bound by S. 1, 1 W&M (1688), Ch VI, (Coronation Oath) and has sworn to govern the people of Australia according to the guaranteed Constitutional

Rights of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, inherited by us as subjects of the

Throne- (eg, the Bill of Rights and the Magna Carta). It is Her duty to preserve the inalienable rights of the subjects. The oath of allegiance prescribed by SS 1and 2,1

W&M 1688 bind the current members of Parliament not to derogate from the

Coronation oath.

124.

The contract between the subject People of Australia and the Monarch on the

Throne of the UK of GB, Queen Elizabeth II, was reconfirmed by the people of

Australia by way of the forced Referendum held on November 6 th

1999.

125.

The fact that we have contracted with the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great

Britain and Ireland

“for the time being”

, means that the legal requirements of the practical constitution go much further than what was superficially approved by the people of Australia in the referendum of 1900. The Sovereign of the United

Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland is legally bound to abide by certain other previous perpetual and thus never ending contracts made by her predecessors with

her people. These include the Magna Carta of 1297 and the Bill of Rights 1688 (in as much as it does not contradict the Magna Carta of 1297).

126.

The Magna Carta clearly states that “The King will not directly or indirectly do anything whereby these concessions may be revoked or diminished”

. Since the sovereign’s consent is required to make or change any laws, the Magna Carta of

1297 is still binding on the British Sovereign today, regardless of whatever nonsense the present highly suspect legal profession may chose to teach.

Furthermore, the Magna Carta of 1297 authorises the people to even go so far as to make war on the Sovereign in his own realm while ever he fails to uphold the terms of the Magna Carta.

127.

The Magna Carta states that “We have granted also, and given to all free men of our realm, for us and our heirs for ever, these liberties underwritten, to have and to hold to them and their heirs, of us and our heirs for ever.

128.

Under these circumstances, any nation which contracts with a rightful heir or a lawful successor to the Sovereign of Great Britain and Ireland, also automatically acquires the full protection of the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1688

129.

All acts to the extent that they purport to confer legislative power in derogation of the Sovereignty of the Queen – in - Parliament at Westminster are null and void.

The Government of Queensland and the Commonwealth of Australia are, to the extent which they claim Sovereignty, in derogation of the Queen -in -Parliament at

Westminster are de facto Governments and are therefore null and void, that is illegal and invalid.

130.

The Queensland government has the power to make rules and regulations for the peace, order and good government of the state. That is provided that the rules and regulations do not derogate from the Sovereignty of the Queen- in – Parliament at

Westminster and provided that the rules and regulations do not violate the inalienable constitutional Rights of the people of Australia.

131.

To obviate all doubts and difficulties concerning the above matters, it was expressly declared by S 12 & 13 Wm. 3, c.2, (Act of Settlement-1701) that

“the Laws of

England (now the UK of GB) are the birthright of the people thereof; and all the

Kings and Queens who shall ascend the THRONE OF THIS REALM, ought to administer the Government of the same according to the said Laws: and all their officers and ministers ought to serve them respectively according to the same: and therefore all the Laws and Statutes of this Realm, for securing the established religion, and the rights and liberties of the people thereof, and all other Laws and

Statutes of the same now in force, are ratified and confirmed accordingly”.

132.

All law has to be assented to by the reigning Monarch therefore guaranteeing no derogation from the Ancient Rights and Liberties enshrined in SS 1 & 2, 1 W&M

(1688) and the Holy scriptures.

133.

If the royal prerogative is used to pass an Act which purports to take away our rights, the judiciary are bound to take judicial notice of it and ignore

The Royal Prerogative

134.

The very beginning of the Constitution Act says we are "under the Crown" and the

Coronation Oath says that the Queen must govern Australia and "execute Law and

Justice with Mercy in all (Her) judgements".

135.

I contend that the Queen was misled by her ministers in giving the royal prerogative to Acts of Parliament that have infringed our liberties.

136.

"No prerogative may be recognised that is contrary to Magna Carta or any other statute, or that interferes with the liberties of the subject”.

137.

The courts have jurisdiction therefore, to enquire into the existence of any prerogative, it being a maxim of the common law that the King ought to be under no man, but under God and the law, because the law makes the King.

138.

If any prerogative is disputed, the Courts must decide the question of whether or not it exists in the same way as they decide any other question of law. If a prerogative is clearly established, they must take the same judicial notice of it as they take of any other rule of law.

139.

The original contract between the Crown and people can be determined using the common-law method for the interpretation of laws by reference to Parliamentary materials. This method of interpreting statutes was restored by the Judgement in the case of Pepper v. Hart (1992). It is required by the Attorney General's Practice

Directions of 1992.

140.

The fact that it is part of the common law, and therefore is not subject to arbitrary change by the Judiciary was recognised by Blackstone; "The fairest and most rational method to interpret the will of the legislator is by exploring his intentions at the time when the law was made, by signs the most natural and probable. And these signs are either the words, the context, the subject matter, the effects and consequence, or the spirit and reason of the law".

141.

The will of the Convention Parliament which drafted the Bill in relation to the subject’s rights was indicated by Sir Robert Howard, a member of the Committee;

"The Rights of the people had been confirmed by early Kings both before and after the Norman line began. Accordingly, the people have always had the same title to their liberties and properties that England's Kings have unto their Crowns. The several Charters of the people's rights, most particularly Magna Carta, were not grants from the King, but recognition's by the King of rights that have been reserved or that appertained unto us by common law and immemorial custom."

142.

Crown servants, such as members of the Judiciary, cannot lawfully subvert the subject’s rights because they have only the same powers and privileges as the people. Any attempt to do so would be ultra vires, which means "beyond their power" and constitute the common law crime of "misconduct in office" .

143.

The case of R v Lord Chancellor ex parte Witham implies that acts of Parliament cannot repeal common law and our rights have fallen into abeyance through lack of a suitable challenge.

144.

Under our system of a constitutional Monarchy, any statute law which in violation of the common law and to the prejudice of the people is void and inoperable and should not be granted Royal assent or if it has (because ministers have misled the governor) should be disallowed by the Governor who took an oath of allegiance to the Queen

145.

The Judges oath of allegiance is to, "do right to all man according to law "- common law that is. He is further directed to take nothing intro consequence or example to the detriment of the subject's liberties (from the Bill of Rights)

146.

Rights granted by imperial enactment such as Magna Carta cannot be taken away or

“overridden” by Politicians or Judges. These rights are inalienable. It is just they are not enforced.

147.

It is stated in the CONFIRMATIO CARTARUM 1297 that:

1) The Magna Carta is the common law and that

2) The Magna Carta is the supreme law. All other contrary law and judgments are void.

148.

It contained the pledge that no free man should have his rights removed without the due process of law and the judgement of his peers. It is taken to be the foundation of the liberties of the citizen in the English-speaking world.

149.

"Here is a law which is above the King and which even he must not break. This reaffirmation of a supreme law and its expression in a general charter is the great work of Magna Carta; and this alone justifies the respect in which men have held it” . --Winston Churchill, 1956

150.

“Hence our …assertion is, that the King’s power of exponing the law is a mere ministerial power, and he hath no dominion of any absolute royal power to expone the law as he will, and to put such a sense and meaning of the law as he pleaseth.”

Rutherford. Lex, Rex. QXXXVII 3,2. And so, too, parliament, and the judiciary.

151.

Chapter 29 of the 1297 charter says:

"No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his freehold, or liberties, or free customs, or be outlawed, or exiled or any other wise destroyed; nor will we not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land. We will sell to no man, We will not deny or defer to any man either justice or right." Edward 1 (1297) Magna Carta

152.

The law of the land does not just mean enacted statute law. It involves the high principles of the rule of law, due process of law, constitutional law, and the rules of natural justice.

153.

That fundamental principle is not repeated in the Australian Constitution, but it has been held by the courts that it is part of our inherited Constitutional law - see ex

parte Walsh v Johnson (1925) 37 CLR 79. There is certainly a presumption in favour of liberty.

154.

The Oxford Dictionary of Law (1990) defines justice as:

Justice: "A moral ideal that the law seeks to uphold in the protection of rights and the punishment of wrongs. Justice is not synonymous with law - it is possible for a law to be called unjust. However, English law closely identifies with justice and the word is frequently used in the legal system."

155.

So, if it is possible for the law of the land to be unjust then the Courts may be restricted to exactly what the law says even though that law may be an unjust law because the courts must exercise the will of the law makers. (ie parliament)

Therefore an unjust law may still be a valid law.

156.

But there are other words in that same sentence and that is the words "or right." So

"justice or right." Or denotes an alternative and right is defined as:

157.

Right: 1. Title to or an interest in any property. 2. Any other interest or privilege recognised and protected by law. Those are plain words with plain meanings.

158.

Therefore, there is an alternative. If a valid law can be unjust then your interests and privileges embodied in Magna Carta are recognised and protected by the word

“right”.

159.

So the lawful judgement of your peers, also in Magna Carta, may hold that while the law may be an unjust law, we are still entitled to be protected by right.

160.

Moreover, can there ever be an adequate justification for the state depriving any person of their constitutional rights?

161.

Lord Robin Cooke formerly President of the New Zealand Court of Appeal, in an extra-judicial paper entitled "Fundamentals" (NZLJ (1988) 164,165) says: 50. "On the other hand, if honesty compels one to admit that the concept of a free democracy must carry with it some limitation on legislative power, however generous, the focus of debate must shift. Then it becomes a matter of identifying the rights and freedoms that are implicit in the concept. They may be almost as few as they are vital...... One may have to accept that working out truly fundamental rights and duties is ultimately an inescapable judicial responsibility."

162.

Indeed, the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares in the preamble: "Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human right should be protected by the rule of law."

163.

".....The rule of law." Not statutory law, Parliamentary sovereignty or otherwise but ,

"....the rule of law”.

I.e. the Courts. Furthermore, the Declaration expressly speaks of the fundamental human right. And that is exactly what this court case is about -

The Rule of Law, fundamental human rights, and the Royal Charter of Magna Carta taking precedence over a pretended Parliamentary sovereignty.

164.

No Parliament has the power to extinguish the right to trial by Jury, as it is an integral part of the Common law, which was assumed by and controls the constitution.

165.

Similarly Cap II of the Confirmatio Cartarum 1297 says that:-

“ and we will, that if any judgement is given from henceforth contrary to the points of the charters aforesaid by the Justices, or by any other offices that hold plea before them against the points of the Charters, they shall be undone and holden for nought”

166.

So the Confirmatio Cartarum further entrenches the rights granted in the Magna

Carta.

167.

The Bill of Rights 1688 is also doubly entrenched by the last paragraph that allows no method of alteration

“And bee it further declared and enacted by the Authoritie aforesaid That from and after this present Session of Parlyament noe Dispensation by Non obstante of or to any Statue or any part thereof shall be allowed but that the same shall be held void and of noe effect Except a Dispensation be allowed of in such Statue [and except in such Cases as shall be specially provided for by one or more Bill or Bills to be passed dureing this present session of Parlyament”

William and Mary Prince and

Princesse of Orange

168.

Trial by Jury is further mentioned in Section 3 of (1627) 3 Charles I. (Petition of

Right) It says: “and where also by the statute called, the Great Charter of the

Libertes of England, it is declared and enacted, that no freeman may be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his freehold, or his liberties or his free customs, or to be outlawed or exiled, or I any manner destroyed, but by the lawful judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land."

169.

And section 8 of this imperial enactment says:-

“that the awards, doings and proceedings, to the prejudice of your people in any of the premises, shall not be drawn hereafter into any consequence or example”

170.

The role of the jury in the protection of liberty has been emphasised by numerous authorities

171.

Trial by Jury has been considered a fundamental safeguard of fairness and impartiality in the administration of Justice, especially of criminal justice. Jury trail stemmed from a deep seated conviction about the exercise of Judicial power, that it should not in matters affecting the liberty of the subject be entrusted unchecked to any official, judge or administrator but should be vested in ordinary citizens. The laws of Australia 21.6, part D, (38), pg 47

172.

In the case of Brown v The Queen the judges in the High Court emphasise the important role that trial by jury has in the administration of justice. On page 179

Chief Justice Gibbs said:

“The requirement that there should be trial by jury was not merely arbitrary and pointless. It must be inferred that the purpose of the section must be to protect the accused -- in other words, to provide the accused with a "safeguard against the corrupt or over-zealous prosecutor and against the

compliant, biased, or eccentric judge"

173.

He goes on to say:

“the jury is a bulwark of liberty, a protection against tyranny and arbitrary oppression, and an important means of securing a fair and impartial trial. It is true that the jury system is thought to have collateral advantages ( It involves ordinary members of the public in the judicial process and may make some decisions more acceptable to the public)” -

174.

This is a common theme in the High Court.

175.

Certainly the judges were very responsive to the idea that there shouldn't be two standards of courts in our country, arguing that to deprive people of a right to a trial by jury and still use the courts when you're doing that, could be impliedly prohibited from the constitution.

176.

Also

“The jury system is fundamental to the administration of the criminal law in

New Zealand. It has as its basis the quality of a collective decision made by a group of ordinary New Zealanders in accordance with their unanimous opinion on whether or not a prosecution brought on behalf of the community has been proved beyond reasonable doubt.”

(Eichelbaum Chief Justice, Greig Justice, Solicitor-

General v Radio NZ (1994) 1 NZLR 48,51.)

177.

I believe that no court has jurisdiction to conduct a trial against me unless it accords me my right to a trial by jury. Other cases without the accused allowed or being given the right to a trial by Jury cannot be held as precedents and cannot affect common law.

178.

The removal of Trial by Jury is illegal and is instituting a system of martial or military law. It is introducing a second class form of justice, one not subject to the people and subjects them to abject slavery.

179.

English Kings have been beheaded or deposed for that very usurpation of the people’s rights, and Parliaments, and individuals, have been bought to book for the same cause.

180.

Earl Grey, in 1831; on the attempted usurpation of prerogative by the House of

Lords said

:“.. But if a majority of this house is to have power, whenever they please, of opposing the declared and decided wishes of both of the Crown and the

People, without any means of modifying that power- then this country is placed entirely under the influence of an uncontrollable oligarchy. I say that, if a majority in this house should have the power of acting adversely to the crown and the

Commons, and was determined to exercise that power, without being liable to check or control, the constitution is completely altered, and the government of this country is not a limited monarchy … but … a separate oligarchy governing absolutely the others.” Hansard debates. 3

Rd

series xii 1006 (May 17 1832)

181.

During the Grand Remonstrance of 1641

“the commons denounced the court

(suzerain) conspiracy (inter alia) to subvert the fundamental laws and principles of

Government…”

182.

And in striking resemblance to contemporary times: “They have strained to blast our proceedings in parliament by wrestling the interpretations…from their genuine intention. They tell the people that our meddling (has caused schisms) when idolatrous….ceremonies…. have …. Debarred people from the Kingdom. Thus with

Elijah, we are called by this malignant party the troublers of the state, and still, while we endeavour to reform their abuses, they make us the authors of those mischiefs we study to prevent.”

Poole, 544-7 Eng. Const. Hist.

183.

Cokes observation was the same:

“The justices extended judicial censorship over legislative acts, and , in effect, adopted Cokes idea of the supremacy of the courts over the other departments of the Government in applying the general doctrine that constitutional grants of power were to be interpreted according to the maxims of

Magna Carta and the principles of the common law, and that the legislatures were limited by superior law, both express, and implied.” And so, too, the judiciary.

184.

“Thus the law of the land was judicially construed to mean that no power was delegated to the legislature to invade the great natural rights of the individual.”

Haines “Natural Law Concepts.”.

185.

“the underlying purpose of most of these limitations was to place the just principles of the common law … beyond the power of ordinary legislation to change or control them.”

Justice Miller, Pumpelly V Green Bay Co., 13 Wall 166, 177 (1871)

186.

However importantly, the Bill of Rights (1 Will & Mary sess 2 c 2 1689) demonstrated that the victors of the Revolution had sought to protect, not to change, the fundamentals of the constitution. The framers of that document were simply declaring law that already existed and would continue to exist. The preamble to the bill reads: "And thereupon the said Lords Spirituall and Temporal, and

Commons......do in the first place (as their ancestors in like cases have usually done) for the vindicating and asserting their ancient rights and liberties declare...."

187.

"Vindicating and Asserting?"

188.

Clearly, the intent and true meaning was not to abolish their ancient fundamental rights and liberties for a pretended parliamentary sovereignty which is generally believed and accepted today. They were vindicating and asserting them, and reclaiming them from a despotic King James II who had grievously violated them.

189.

Sir Robert Howard, a member of both Treby's and Somer's Rights Committee's, said during the Bill of Rights debate;- "Rights of the people had been confirmed by earlier Kings both before and after the Norman line began. Accordingly, the people have always had the same title to their liberties and properties that England's Kings have had unto their Crowns. The several Charters of the people's rights, most particularly Magna Carta, were not grants for the King, but recognition by the

King of rights that have been reserved or that appertained unto us by common law and immemorial custom."

190.

The intent throughout the debate was clear; - Reserved fundamental rights.

191.

The British Parliament has confirmed the continued existence of the Bill of Rights

(1688):

192.

The Judgement in Pepper v. Hart in 1993 was referred to in (UK) Parliament and caused The Speaker of the House of Commons to issue a reminder to the Courts and all other persons of their duty to take notice of the Bill of Rights, further confirming that it is an operative Statute. She said; "This case has exposed our proceedings to possible questioning in a way that was previously though to be impossible. There has of course been no amendment of the Bill of Rights ... I am sure that the House is entitled to expect that the Bill of Rights will be required to be fully respected by all those appearing before the Courts" (UK) Hansard, 21 July 1993.

Stare Decisis

193.

I believe that precedents opposed to Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights can be covered by the term stare decisis - a doctrine giving to precedent the authority of established law.

194.

However, Chief Justice Brandeis said in Di Santo v. Pennsylvania, 273 U.S. 34

(1927) 42 " Stare Decisis is not a universal inexorable command. It does not command that we err again when we have occasion to pass upon a different statute."

195.

A decision is not binding on a subsequent Court simply because it was made in the past. Courts are not bound as a matter of law by the doctrine of precedent. Some decisions are to be regarded as persuasive rather than strictly binding.

196.

I believe that it is necessary to distinguish the intent of the originators of Magna

Carta and the Bill of Rights in allowing freedoms, from subsequent decisions that may seem to limit those freedoms. Such a distinction would allow a more restrictive scope of interpretation of those precedents and laws. In such an important issue as trial by jury it is not unlikely that they got it wrong.

197.

Your Honour the Queen has sworn to God to uphold the Magna Carta. Judges have sworn to God and the Queen to uphold the Common law. I ask you to fulfil your oath to God and the Queen and give me my rights to a trial by Jury

HUMAN RIGHTS

198.

The High Court of Australia has already held that lack of representation in a trial for a serious criminal offence is likely to prejudice the right to a fair trial. Dietrich v R

(1992) 109 ALR 385

199.

An offence against the Weapons act is a criminal offence that affects my right to have weapons for the rest of my life. There may be a prison term involved. I have been refused legal aid and the HREOC has previously refused my applications.

200.

All gun owners who have refused to obey the New Gun Laws are all similarly disadvantaged in the refusal of legal aid to assist my case and the refusal of rights to trial by Jury and the refusal of the HREOC to act. The Gun laws have become a

case of Judicial co-operation in the enforcement of Parliamentary decrees. The

Judiciary is not seen to be independent nor just.

201.

That my arguments have been ignored in all previous courts indicates that I am unlikely to get a fair trial without legal representation.

202.

I am entitled to legal representation under the Federal Legislation of the Human

Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act of 1986 and the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

203.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights has been enacted into law as the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act of 1986.

204.

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares in the preamble:

"Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human right should be protected by the rule of law."

205.

".....The rule of law." Not statutory law, Parliamentary sovereignty or otherwise but,

".... The rule of law ”. Ie. The Courts.

206.

Furthermore, the Declaration expressly speaks of the fundamental human right taking precedence over a pretended parliamentary sovereignty. Since Government has also ratified that UN Declaration, and the Parliament has not expressly repealed it, logically it follows that it must have intended to be taken seriously. (See R v

Immigration Appeal Tribunal, Ex Parte, Manshoora Bengum (1986) Imm AR 385

(QBD) Simon Brown J.)

207.

Since the laws of the Commonwealth apply to Queensland the Human Rights and

Equal opportunities Act applies to Queensland. Article 50 ICCPR. "The provisions of the present covenant shall extend to all parts of Federal states without any limitations or exceptions."

208.

Also Clause 5 of the Constitution Act UK says that all laws made by the Parliament of the Commonwealth are binding on the Court, Judges and People of every State not withstanding anything in the laws of any State.

HUMAN RIGHTS AND EQUAL OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION ACT 1986

(Updated as at 26 September 1995) Section 3

209.

(4) In the definition of "human rights" in subsection (1): the reference to the rights and freedoms recognised in the Covenant shall be read as a reference to the rights and freedoms recognised in the Covenant as it applies to Australia; and the reference to the rights and freedoms recognised or declared by any relevant international instrument shall:

210.

in the case of an instrument (not being a declaration referred to in subparagraph (ii)) that applies to Australia - be read as a reference to the rights and freedoms recognised or declared by the instrument as it applies to Australia; or in the case of an instrument being a declaration made by an international organisation that was

adopted by Australia - be read as a reference to the rights and freedoms recognised or declared by the declaration as it was adopted by Australia.

211.

SCHEDULE 2, Section 3 INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON CIVIL AND

POLITICAL RIGHTSPART II Article 14

212.

3. In the determination of any criminal charge against him, everyone shall be entitled to the following minimum guarantees, in full equality; To be informed promptly and in detail in a language which he understands of the nature and cause of the charge against him; To have adequate time and facilities for the preparation of his defence and to communicate with counsel of his own choosing; To be tried without undue delay; To be tried in his presence, and to defend himself in person or through legal assistance of his own choosing; to be informed, if he does not have legal assistance, of this right; and to have legal assistance assigned to him, in any case where the interests of justice so require, and without payment by him in any such case if he does not have sufficient means to pay for it;

213.

Australia is a signatory and fully committed member of the United Nations and has undertaken to honour and obey the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights.

214.

In 1994 Nicholas Toonen of Tasmania Australia successfully complained that his

Human Rights were violated by the Tasmanian Criminal Code and the United

Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva upheld his complaint and Tasmania agreed to repeal the offending legislation.

215.

My civil rights have been successively violated by the failure of the legal system in

Queensland to honour and uphold the principles outlined in the Human Rights and

Equal Opportunity Commission Act of 1986. Schedule 2.

216.

By Article 50 of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act of

1986. Schedule 2, Queensland is bound by the Covenant.

217.

The Violations that have occurred are,

218.

(a) In Part 2 Article 1, I have been discriminated against by Queensland Courts I have appeared before because I did not have legal representation. I am in a lower socio economic class than the State of Queensland which can afford the most expensive representation and was thereby denied equality of opportunity to receive justice.

219.

(b) In Article 2 Queensland and Australia has undertaken to promote equality of opportunity and Queensland has in place laws, Sections 51 and 243 of the Supreme

Court Act 1995 which recognise the equality of the said Martin Essenberg with

McPherson JA, Chesterman J, Boyce QC, Mr Smith SM and Mr Lebsanft SM and require those judicial persons to obtain the consent in writing to sit without a jury before they may make any binding order. This Right was violated on every occasion.

220.

(c) Article 5 (2) recognises the fundamental Human Right to be adjudged by a jury of ones peers unless consent to sit without is first had, as is the Civil Right of All

Queenslanders.

221.

(d) Article 7 is violated when Justice is delivered in a degrading way, without the consent of the litigant. It is Internationally accepted that it is not degrading to be adjudged by a jury of one's peers.

222.

In Mabo v Queensland [No. 2] , the High Court through Justice Brennan's leading judgment, held that it was proper for courts in Australia to have regard to international human rights jurisprudence in developing the common law and in resolving ambiguities of legislation. It was said that this was an inevitable process, once Australia signed the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on

Civil and Political Rights . This action rendered Australia accountable in the international community for breaches of fundamental rights

223.

Dietrich v The Queen . There it was held that, in certain circumstances, a prisoner facing a serious criminal charge, must be provided with legal counsel if to deprive him or her of such expert representation would render a trial unfair. Even more lately, the High Court has found constitutional rights implied in the Constitution.

Thus, the right to free public discussion of matters of politics and economics were found, in the Capital Television decision, to be inherent in the very nature of the

Australian representative democracy established by the Constitution.

224.

I believe the interests of Justice for myself and all other gun owners require that I have legal representation. The validity of the New Gun Laws needs to be tested properly as does the right of Parliament to further control and manipulate what goes to Juries and what does not. Due to lack of legal support this could not be done in my previous trials

The Australia Act

225.

In Essenberg v The Queen (B55/99) the respondents argument sought reinforcement for the notion that State law legislation is autochthonous law and thus unable to be challenged by reason of same, and furthermore, that the Australia Act, specifically

Sec 3, subsection 2, some how provides for unrestrained autonomy of law making by the state of Queensland.

226.

The passages of the Australia Act 1986 through all Australian parliaments without dissenting voices were themselves without substance and void since they were in clear breach of our Australian Constitution on more than one fundamental ground.

227.