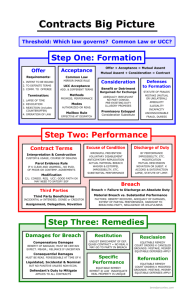

Discharge by Performance

advertisement

Discharge by Performance

Element 1: Definition of discharge by performance

- For discharge by performance to occur, the contract must be exactly or substantially

performed, to allow for recovery of the contract price.

- Partial performance does not allow for recovery of the contract price but payment

may be recovered in restitution for the work.

- Failure to perform a contract according to its terms will be a breach of the contract

Element 2: Nature of Obligations

Sub element 1: Independent Obligations

- On party must perform regardless of whether the other

- E.g. a sale of goods contract may provide for payment on a certain day whether or

not the goods are delivered by that day.

- Provided that any conditions precedent have been met, the contract price will be

payable.

Sub element 2: Dependent obligations

- One party must perform his or her obligations before the other.

- E.g. a sale of goods contract where the buyer is not required to pay for goods until

the seller ~ the goods and they are accepted by the buyer.

- Until the seller delivers the goods in accordance with the contract, the seller is not

entitled to sue for the contract price of the goods.

- If the goods are not accepted by the buyer, the seller's only claim is for damages for

breach and not for the contract price, because the contract price is payable for the

actual goods and not the promise to deliver them. Automatic Fire Sprinklers Ltd v

Watson

- Look to the performance.

Sub element 3: Dependent and Concurrent Obligations

E.g. in a sale of land contract where the purchaser pays the purchase price in exchange for,

and at the same time as, the vendor delivers title and possession of the property to the

purchaser.

Any failure to perform will generally NOT be considered of a minor nature.

Element 3: Type of Contract

Sub element 1: Divisible Contracts

This is a contract where the consideration and the payment thereof is apportioned or is

capable of apportionment according to the work to be done. (Steele v Tardiani)

- The Court considers: o Each divisible part separately as if they were different agreements.

o Only the obligations relating to that particular divisible part of the contract

- The party performing the contract is able to recover after each part of the contract

notwithstanding the whole of the contract is not completed.

Sub element 2: Lump sum contracts

A contract that provides for the payment of a specific sum for the completion of specific work.

- Court considers:o The whole of the performing party's obligations under the contract

o Whether the performance that was rendered satisfied the requirements of the

contract as a whole.

- Hoenig v Isaacs [followed in Queensland in Lemura v (Coppola)

Element 4 – Nature of the Obligation

Sub element 1 – Entire Obligations

- This requires exact performance of the entire contract before the contract price can

be paid. In the case of a divisible contract, it requires exact performance of that

particular part of the contract.

Usually occurs in contracts where the terms clearly indicate that 'the consideration for

the Payment of money or for the rendering of some other counter performance is

entire and divisible.' Baltic Shipping Co v Dillon

- Essential features are: o Complete performance is a condition precedent to payment of the contract

price

o The benefit expected by the defendant is to result from the enjoyment of

every part of the work jointly; and

o The consideration is neither apportioned by the contract nor capable of

apportionment.

Cutter v Powell

Facts:

- Seaman working on ship from Jamaica to Liverpool for 30 guineas on arrival provided

he worked for period of voyage died 6 weeks into 2 month voyage

- Administratrix commenced an action for the contract price or quantum meruit

HELD:

Contract entire and therefore could not recover either

- Court influenced by: o Cutter required to do duty for whole voyage

o Lack of prevailing custom

o Significantly high amount of money payable under contract comparable with

the monthly wage.

o Therefore parties intended an all or nothing result

-

Sub element 2 – Not entire obligations

The fulfilment of every part of the contract price is not necessarily essential to payment of the

contract price even though the obligations of the parties are dependent.

Element 5: Nature of Performance

Sub element 1: Exact Performance

If the contract was performed exactly the party is entitled to the contract price

Sub-element 2: Partial Performance

- Despite the fact the contract price may not be recoverable a party to the contract may

be able to seek alternative remedies.

- The first alternative is for the party who has undertaken work or provided goods to

seek damages for the breach of the other party.

o Damages may be claimed only if the party seeking them is not themselves in

breach.

- The second alternative is to make a claim in restitution for the return of a benefit

provided to the other part.

o The only type of restitutionary claim relevant to this context is a claim for

quantum meriut for the value of serves provide to the other party.

The party is entitled to a quantum meruit or the choice of quantum meruit and damages

depending who was in breach.

Application to Divisible Contract

- A party who only partially performs a severable part of the contract is not entitled to

the contract price for that part unless the other party has prevented performance or

the work has been accepted (Steele v Tardiani).

Application to a Lump Sum contract

- A party who partially performs a lump sum contract will not be entitled to the contract

price.

- They may be entitled to damages or a quantum meruit in certain circumstances. See

Appleby v Myers and Automatic Sprinklers v Watson

Sub element 3: Substantial performance

- Will occur where the defects in the services or goods are of a minor nature. The court

takes into account:

o The nature of the defect; and

o The cost of rectifying the defect compared to the contract price.

- Where the contract does not clearly and expressly provide that exact performance is

a condition precedent to the payment of the contract price, the court will lean against

a construction that would deprive the party any payment simply because of defects.

- If a contract or part of a divisible contract is substantially performed the party will be

entitled to the contract price less an amount for rectifying the defects in the

performance.

Hoeniq v Isaacs

Facts:

- P agreed to decorate and furnish D's flat for 750

- D paid 400 as progress payments

- When work was finished door of wardrobe needed replacing and too short book shelf

for 55.18

HELD:

- As p had substantially performed contract, he was entitled to payment less an amount

for rectification

Bolton v Mahadeva

Facts:

- P agreed to install water heater for 560

- Installed water heater gave out fumes and didn't work properly

- P claimed payment of contract price

- Court took into account

o Heating system did not heat house adequately

o Gave out fumes

o Cost of rectification 174 pounds

HELD:

P had failed to substantially perform obligations

The court took into account:

- Where nature of defect is minor and cost of rectification is 10% or less court will allow

recovery for substantial performance [Hoenig]

- Where nature of defect is minor and cost of rectification is 10% or more court will

allow recovery for substantial performance, subject to cost of rectification not

exceeding a reasonable amount

- Where nature of defect is serious and cost of rectification is 33% or more court will

refuse recovery for substantial performance [Bolton]

- Where nature of defect is serious and cost of rectification is 10% or less it is unlikely

contract price will be recoverable

Application to Divisible contract

- The principle of substantial performance will apply to each part of a divisible contract

as if it were a separate contract.

- Therefore, a person who has substantially performed a part of the contract is entitled

to be paid for that part less damages for any defective performance.

- Substantial performance will not apply if the severable parts of the contract are

considered to be entire (Steele v Tardiani).

Application to Lump sum contract

- The court will look to the whole of the performance as compared to the whole of the

required performance under the contract.

- If the obligations are entire, the doctrine of substantial performance will not apply.

Element 6: Effect of Termination

Termination by Party not in breach

- If the party obliged to pay the price has validly terminated the contract for a breach of

the party performing the work, it will generally mean that the party obliged to perform

the work has not substantially performed the contract

- If the D has substantially performed then the termination is invalid

Termination by Party in breach

- If the party undertaking the work has validly terminated the contract for a breach of

the party obliged to pay the price, a claim for the contract price will only succeed if

there is an accrued right to claim the right prior to the termination

Element 7: Recovery by Parties

To establish the rights of a party who has performed work under a contract it is necessary to

distinguish between a party in breach and one who is not in breach of the contract:

Quantum Meriut

- Quantum meruit is a claim for the reasonable value of the work performed by the

party. Only available for part performance

- The claim is only available once the contract has been terminated or rescinded. The

basis of the claim is the return of a benefit or monies worth, which has been given to

the defendant in circumstance where the defendant should be required to pay for the

benefit.

- Unlike contractual damages recovery of a quantum meruit is generally unrelated to

fault and is premised upon three elements:

o Has the plaintiff provided a benefit to the defendant?

o Was the benefit provided at the expense of the plaintiff?

o Is it unjust that the defendant retains the benefit?

Sub element 1: Party not in breach

- A party who is not in breach under a contract where services have been provided will

be able to seek compensation for the work performed. The party may elect to seek

compensation on the basis of either:

o A quantum meruit; or

o Damages.

- The party will not be entitled to both damages and a quantum meruit and will need to

elect between the remedies at judgment.

- If the party has performed his obligations exactly or substantially then a claim lies on

the contract price and quantum meruit cannot be sought as the contract cannot be

terminated for breach

Provision of Benefit

- Generally considered objectively

Sub element 2: Party in breach

- Where the party who has performed services is in breach of the contract the

potential for compensation is limited to a claim for quantum meruit because they

cannot rely on their own breach to obtain a benefit under the contract.

Provision of Benefit

- Will be unable to prove that a benefit was provided to the D because where a

defendant has not received what they expected under the contract, the defendant

may subjectively devalue the work.

o The defendant may allege that as the work is only partially complete, it is of

no benefit to him or her. For this reason services will generally only be

considered to provide a benefit if;

The services performed were requested by the defendant; or

The services were freely accepted; or

The defendant has obtained an incontrovertible benefit from the

services.

Services

- It will be insufficient in a claim for quantum meruit by the party in breach to merely

show the services were requested.

- Despite the fact work may have been requested by the defendant, the problem will be

that the work provided will usually not match the request.

- It will be difficult for the plaintiff to convince a court that work that does not comply

with a request actually provides a benefit to the defendant except where the other

party prevents the performance of the agreement: Planche v Colburn

Freely Accepted

The concept of free acceptance means that the defendant has a choice whether to accept or

reject the work and has freely decided to accept the work that does not comply with the

contract. Where the work concerns improvements to land the plaintiff will have a very difficult

task in proving free acceptance.

Sumpter v Hedges

Facts:

- P agreed to build 2 houses and a stable for the D for 565

- P did part of the work amounting to 333 and received payment of part of it

- Informed D he could not go on

- D finished building using materials p left behind

Held:

- P was awarded value of materials left behind

- Refused claim of quantum meruit because in work done on land D does not have

much choice of free acceptance

Incontrovertible benefit

- Arises where the D has converted goods or services provided by the p into money in

the hands of the D

Steele v Tardiani

Facts:

- D employed P to cut firewood and alleged p were in breach because wood wasn't cut

into correct lengths

- However D sold all wood

HELD:

- Contract was divisible so p were entitled to be paid for any wood cut into correct

lengths

- Entitled to recover on quantum meruit for remaining timber split

Termination by Frustration

Termination by frustration will occur where subsequent to a contracts formation a change of

circumstances beyond the control of either of the parties renders the contract impossible to

perform because performance would render it a thing radically different from that -which was

undertaken by the contract. Codelfa Construction Pty Ltd v State Rail Authority of NSW

There is no frustration just because performance of a contract becomes more onerous or

inconvenient or expensive. The Eugenia

Element 1: Has Frustration Occurred?

Sun element 1: Destruction or unavailability of subject matter

- This occurs where without the fault of either party; the specific subject matter of the

contract is destroyed or lost to the parties e.g. through fire, or being resumed by the

government

- It will not occur where one of the parties has expressly or impliedly agreed to bear the

risk of destruction.

Taylor v Caldwell

Facts:

- Hall destroyed by fire

Sub element 2: Death or Incapacitation of person essential for performance

- Occurs in a contract for service

- Includes illness, imprisonment, conscription...

- The effect of illness will depend on: o Nature and probable duration of illness

o Terms and nature of contract; in employment contracts that provide for sick

leave, the contract may be frustrated when all the sick leave benefits expire.

- Simmons Ltd v Hay

- Carmichael v Colonial Sugar Ca Ltd

- Finch v Sayers

Sub Element 3: Failure of basis of contract

Occurs where an event that the parties have agreed to as the basis of the contract does not

occur

Krell v Henry

Facts:

- Coronation of Edward VII

- Hired a flat to watch the procession

- Coronation was cancelled

Held:

- Frustrated because watching the procession was the basis of the contract

Event must be true basis of contract and not mere co-incident:

Herne Bay Steam Boat Co v Hut ton

Facts:

- Coronation of Edward VII

- Hired a yacht to look at fleet

Held:

- Coronation was cancelled

- Not frustrated because he could still watch the fleet

Sub Element 4: Method of Performance Impossible

- Contract must expressly provide for a particular method of performance; OR

- It must be stipulated or contemplated by both parties in circumstances necessitating

that method: Codelfa

Sub Element 5: Excessive Delay

- Past or prospective delay in performance:

- Will depend on:

o The probability of the length of the delay

o The time left to run on the contract: Pioneer Shippinq Ltd v BTP Tioxide Ltd

- Sometimes a party is not bound to wait for the delay to occur but can immediately

treat the contract as discharged

- Others will require the parties to wait and see:

o Embiricos v Sydney Reid & Co

o Pioneer Shil1oinq Ltd v BTP Tioxide Ltd

- Events are not judged with hindsight: Court Line v Dant & Russell

Sub Element 6: Illegality

Performance rendered legally impossible by: - Changes in Law

o After the contract is performed, the law may change in such a way as to

prohibit further performance of the contract and the contract will be

discharged

o Attention must be paid to the terms of the contract and the surrounding

circumstances

Scanlon’s New Neon v Tooheys

Facts:

- Leased neon sign.

- Under war powers illumination was prohibited at night.

- P claimed K was frustrated.

Held:

- K was not frustrated because it was easily seen during the day and thus retained

significant advertising value, though less than what the P expected.

-

Contracting with the enemy

o Any contract between Aus and a country it is at war with will be illegal

o May also be illegal if the contract provides assistance to the enemy prohibits

the prosecution of the war

o Fibrosa v Fairbairn

o Hirsch Zinc Corporation Ltd

o Metropolitan Water Board v Kerr

Sub Element 7: Land Contracts

Sale contracts

- Upon execution of a contract of sale, the purchaser acquires an equitable interest in

the land

- If there is a radical change in circumstances between the time of the contract and the

time of settlement that prevents the vendor from transferring legal estate, specific

performance will no longer be available

- Therefore the purchaser cant be treated as the owner in equity and the contract will

be frustrated e.g. where

o Government resumes the land

o Landslide destroys the land

- In a sale of land that includes a building, and the building is destroyed, the contract is

not frustrated because the purchaser can still acquire legal interest of the land.

- Austin v Sheldon

- Holland v Gold trans Pty Ltd.

Leases:

- Agreement to lease confers an equitable interest on the lessee while an actual grant

of the lease transfers legal estate

-

In Codelfa, the court followed the English ruling of National Carriers v Panalpina

(Northern) Ltd. The court takes into account: o The duration of the lease and the time left to run on it after the frustrating

event

o The nature and object of the lease

o Length or prospective length of the frustrating event

Element 2: Are there any limits that apply?

Sub element 1: Express contractual provisions

-

The event must not be provided for in the contract:

Where the contract expressly provides for dealing with the event, the parties will be

taken to have provided for its occurrence

-

Claude Neon v Hardie

o K provided for P to ask for rent balance if interest of lessee in premises was

extinguished or transferred

o Premises resumed by Government

o D argued frustration

HELD:

o Resumption amounted to extinguishment of interest and therefore there was

no frustration because it had been provided for in the contract

o Must be distinguished from force majeure clauses, which provide for a

number of events and then provide for consequences in case the event

occurs e.g. "strikes, floods, war..."

-

Sub Element 2: Event Foreseeable

-

-

-

In general, the event must not have been foreseen by the parties, apart from the case

of intervening illegality:

Reference must be made to what was originally contemplated by the parties; this

depends on: o Express provisions in the contract

o Nature of the contract

o Surrounding circumstances

Where the supervening event was, or should have been, foreseen by the parties as a

serious possibility, but for which they did not make express provision, the inference is

that they have nevertheless assumed the risk of the event occurring.

Event must be a "serious possibility' and not 'reasonably foreseeable'

Even where the event is foreseeable, it may frustrate the contract where the effect of

the interference exceeded anything that was contemplated.

WJ Tatem Ltd v Gamboa

Facts:

- Vessel chartered for 1 month by Republicans to evacuate people

- Contemplated that vessel might be detained for a short while by Nationalists, so D

paid 3 times market hire rate in advance

- Vessel seized for 2 months

- P claimed additional payment for 2nd month

HELD:

- Although both parties contemplated the event it exceeded anything that was

contemplated therefore K frustrated and claimed hire not payable.

Sub element 3: Event induced by one of the parties

-

The event must not be due to the "fault" of one of the parties: o Where brought about by deliberate act of one of the parties, OR

o Due to the negligence of one of the parties depending on: Degree of seriousness of the negligence

-

-

Closeness of the cause between the negligence and the frustrating

event

Whether the negligent conduct was directed toward the performance

of the contract

Whether contract commercial or personal

Where party enters into a no of contracts and has a real choice whether to fulfill one

contract out of a number, the act leading to the failure to perform may be self induced

frustration. Maritime National Fish v Ocean Trawlers

Onus lies on person who makes the allegation of self-induced frustration. Joseph

Constantine v Imperial Smelting

Element 3: What will be the effect of the frustration?

Discharge

- Frustration automatically discharges a contract as to the future at the time of the

frustrating event: Hirji Muiji v Cheong Yue Steamship Co Ltd.

- Discharge by force of law so not necessary to elect to terminate contract

Voidable

Unconditional rights accrued before frustration remains enforceable;

Obligations not yet accrued are discharged. But some clauses may continue to bind the

parties: eg arbitration clause: Codelfa

Total failure of consideration

- The loss arising from the discharge lies where it falls unless there is a total failure of

consideration.

- Rights accrued before frustration will be unenforceable if there is a total failure of

consideration. Fibrosa SA v Fairbairn. Lawson Ltd

Quantum Meruit

- Work done under the contract after frustration may be claimed on a quantum meruit

basis: Codelfa No.1

Damages

- Neither party is entitled to damages after frustration.

Termination by Agreement

Definition

- Parties to an existing contract can make an agreement to extinguish the rights and

obligations it has created

- An agreement is itself a binding contract provided it is either made under seal or

supported by consideration.

Element 1: Has there been an agreement?

There must be: - Offer

- Acceptance

- Consideration

- Clear intention to bring the parties obligations to an end

Sub Element 1: Is there consideration?

Where neither party has performed their obligations: - The consideration is the mutual release by each party of the other from performance

of outstanding obligations.

- Bilateral discharge may be an agreement to discharge the contract without replacing

it. Or to discharge the contract and replace it with another contract.

Where one party has completely performed his or her side of the contract: - Consideration must be under seal or be supported by fresh consideration. Accord and

satisfaction: McDermott v Black.

Compromise of a cause of action [Accord and Satisfaction]

- Agreement to relinquish a cause of action against a party may act as a discharge of

the original agreement

- The accord is the agreement by which the obligation is discharged

- The satisfaction is the consideration which makes the agreement operative

Accord Satisfaction

- The original agreement is discharged immediately the compromise agreement is

entered into

- The agreement itself releases the cause of action and is substituted in its place

- Discharges the original agreement immediately

Breach

- If a party breaches an accord satisfaction; the innocent party will be forced to

seek: - Damages for the breach of the compromise or

- Specific performance

- Original agreement will not be revived by the breach

Accord Executory

- The compromise is a promise to release the cause of action only once the event set

out in the compromise occurs

- The original cause of action will not be discharged unless the promised conduct

occurs

Breach

-

If a party breaches an accord satisfaction; the innocent party will be entitled to: Revive the original cause of action; or

Seek Specific performance

Fraser v Elgen Tavern

Element 2: Has there been a variation?

- Variation leaves the original contract on foot but modifies some particulars

- Requires all the things that a valid agreement requires

Element 3: Requirement of Writing

Discharge:

- An oral agreement to discharge a contract will be enforceable even if the agreement

was of a type required to be in writing. Tallerman & co v Nathan’s Merchandise

- The oral agreement is not in itself enforceable but will be enough to discharge the

original contract. Morris v Barron

Variation

- An oral agreement to vary an oral contract is enforceable; an oral agreement to vary

a contract in writing will not be enforceable. Tallerman

- In an oral agreement to terminate a contract required to be in writing and replace with

a new contract, the termination will be operative but the new contract will be

unenforceable. Tallerman

- Dispensation of mode of performance (i.e., extending time frame for performance) will

be enforceable even if the K is one required to be in writing. Phillips v Ellinson Bros

Writing then original contract remains on foot Australian Provincial Association Ltd v

Ragers (1943) 43 SR (NSW) 202.

Element 4: Non-Contractual Discharge:

-

-

Abandonment will occur where an inordinate length of time has been allowed to pass

during which time neither party has attempted to perform or called on the other to

perform

Fitzgerald v Masters

Termination for Breach

Element 1: Has there been a Breach

- A right to terminate for the breach of a term of a contract will arise either:

- Pursuant to the contract.

- Pursuant to common law. This will occur where there is: - A breach of an essential term, or

- A serious breach of an intermediate term.

Sub Element 1: Contractual Right of Termination

- Depends upon the construction of the contract

- Events that activate the contractual right must occur

- Innocent party must exercise the right of termination

- Contractual right will be construed strictly

- Claim for damages will depend on the injured party's proving that the term breached

is essential or that a repudiation has occurred

Sub element 2: Breach of an Essential Term

- Ascertained by reference to: o The contract as a whole and

o The intention of the parties

Luna Park (NSW) Ltd v Tramways Advertising Pty Ltd

- Test of essentiality

- Promise is of such importance to the promisee that he would not have entered into

the contract unless he had been assured of a strict or substantial performance of the

promise and this ought to have been apparent to the promisor

- All breaches of the term will allow the innocent party to terminate the contract

Express terms

- 'Time is of the essence' is strictly construed as an essential term

- A provision in the contract for a right to terminate the contract for a breach of the term

will also be construed strictly

- Innocent party will need to elect to terminate the contract

- Court will have regard to: o Conduct of the parties following a breach of the term

o Motivation for entry into the contract

o Whether the term itself was set out clearly and concisely

o What the consequences of breaching the term will be

Implied Terms

- Implied by statute

o Statute will regularly provide for the effect of breaching such a term

o Effect of the implied term may not as a rule be altered by the parties

- Implied by common law

o Classification depends upon the construction of the contract and possible

intentions of the parties

Sub Element 3: Serious breach of an intermediate term

Will give rise to a variety of breaches

Depends on:

o The seriousness of the breach and

o Consequences both actual and foreseeable

o If consequences deprive innocent party of substantially the whole of the

benefit of the contract termination will be possible

o Where consequences are less serious the innocent party will be limited to

damages

Hong Kong Fir Shipping case [1962] 2 QB 26

Bunge v Tradax [19BI] I WLR 711.

Termination by Repudiation

- A repudiation occurs when a party:

o Renounces his liabilities under the contract

o Evinces an intention either expressly by words or impliedly by conduct, no

longer to be bound by the contract; or

o Indicates clearly an intention to perform the contract in a manner substantially

inconsistent with is obligations

- The refusal or inability to perform must relate to the contract as a whole, or to an

essential respect

- Promisee must elect to terminate the contract

Element 1: Anticipatory Breach

- A repudiation before the time fixed for performance is called an "anticipatory breach".

- The innocent party may elect to treat the contract as discharged and sue for damages

without waiting for the time for performance to arrive.

o Breach must be of a sufficiently serious nature

o This right of termination is subject to the restriction that the innocent party

need only show that at the time of the anticipatory breach he or she was not

wholly or finally disabled from performing the contract; Foran v Wight.

- Promisee may wait until the time for performance and accept the failure to perform

as an actual repudiation of the contract or a breach of an essential term

o Breach must be accepted before it is acted upon

o If innocent party does not elect to terminate contract prior to time for

performance the contract will continue on foot for benefit of both parties

o Possible for repudiating party to change his mind and complete the contract

Element 2: Application to Leases

- Delivery of a notice to lessee to rectify breach will be a prerequisite to exercising a

right to terminate for repudiation

- Right to damages will depend on the existence of a breach of an essential term or a

repudiation of the contract notwithstanding there is a clause in the contract giving

the lessor a right to terminate if the lessee is in default of any clause of the lease

- Doctrine of surrender of leases; o If the ct considers that the lessor actually accepted a surrender of the lease

rather than terminating for repudiation no damages for future rent are

available

Element 3: Proof of Repudiation

- Reference to D's words or conduct

o No requirement for proof that the D is also unable to perform

- Reference to D's position; that is, whether on the basis of surrounding facts they are

in a position to perform

o P required to prove D was unable to perform at the time for performance

Element 4: Examples of Repudiation

Sub element 1: Repudiation by words or conduct

Express refusal

- Refusal to perform all the obligations will dearly amount to repudiation

o Hochster v de la Tour

o D agreed to employ p as a courier

o Before p started he was told his services no longer required

o HELD; D had repudiated all his obligations under the K

- Refusal to perform some of the obligations may amount to repudiation if refusal is of a

sufficiently serious matter

o Associated News v Bancks

Implied refusal

- May be implied from party's words or conduct where a reasonable person in the

shoes of the innocent party would clearly infer that the other party would not be

bound by the K or would fulfil it only in a manner substantially inconsistent with that

party’s obligations and in no other way. Laurinda v Capalaba Park Shopping Centre

Unjustifiable interpretation of the contract

- Party acts or; an erroneous construction and breaches one or more terms or

- Evinces an intention not to perform except in accordance with the erroneous

interpretation Luna Park (NSWJ Ltd v Tramways Advertising Pty Ltd

- DTR Nominees Pty Ltd v Mona Homes Pty Ltd

- However, before termination an attempt should have been made to persuade the

party of the error of its ways, or to give it an opportunity to reconsider

- Court distinguished two instances

- Where in the face of adverse comment a party insists on an interpretation of

the K which is not tenable [repudiation]

- Where the party although asserting a wrong view is willing to perform the K

rightly

Wrongful termination of the contract

- Where a party purports to terminate a contract in circumstances where he has no

legal right to do so the party's conduct will constitute a repudiation

- The termination will therefore not be effective

- Innocent party will still have to elect to terminate

- Braidotti v Qld City Properties Ltd

Commencement of proceedings

- Will not amount to repudiation unless proceedings commenced in such

circumstances as to make it plain that the party commencing them evinces an

intention not to be bound irrespective of the outcome

- Lombok Pty Ltd v Serpentine Pty Ltd

Sub element 1; Repudiation based on Inability to perform

- Express declaration by words or acts - Faran v Wight

- Implied inability - P must prove that the D is wholly and finally disabled from

performing Necessary to prove D's actual position rather than what he said or did

Element 5:

- Must be accepted by terminating the K

Element 6: Termination for Delay in Performance

A contract may be terminated for a delay in performance of the agreement. This is in essence

an example of a situation where a party may be entitled to terminate for breach of a term of

the contract or for a repudiation depending upon the circumstances.

- If time is expressly or impliedly of the essence of the agreement, failure to perform

on the date specified will be a breach of an essential term of the contract allowing

the innocent party to terminate.

- If time is not of the essence of the agreement termination is only possible where:

o A notice making time of the essence has been served and the other person

fails to comply with the notice; or

o No notice is served making time of the essence but the conduct of the person

is such to amount to a repudiation of the contract.

Sub Element 1: Time of the Essence

Timely performance will be of the essence where:

- The contract expressly so stipulates: Harold Wood Brick Co v Ferris; or

- The surrounding circumstances or the subject matter make it imperative that the

agreed date be precisely observed: Bunge Corp v Tradax SA; or

- The terms of the contract are such that time of the essence should be inferred: Wocal

Investments v Hurley

- See also Sale of Goads Act 1896 (Qld), s 13(1) which provides for the effect of time

stipulations in contracts for the sale of goods.

If a time stipulation is of the essence failure to perform the contract on time will allow the

innocent party to terminate the contract for breach of a term immediately.

Examples of time of the essence

Commercial contracts

- In commercial contracts time stipulations are generally regarded as essential: Bunge

v Tradax

- If a date for performance of the contract is stipulated then a failure to perform on that

date will entitle the innocent party to terminate the contract.

- In general equity follows and upholds the common law in these situations.

Land contracts

- Payment of a deposit on time is prima facie essential because of its special character

as an earnest of performance: Brien v Dwyer

- Failure to pay a deposit is a breach of an essential term entitling the innocent party to

terminate the contract.

- Payment of the balance of the purchase monies is subject to the rules of equity

concerning time performance in contracts for the sale of land.

-

-

-

-

At Common law, time is of the essence if the contract expressly so stipulated or

the contract named the date of completion. The innocent party could terminate

forthwith.

In Equity, however, time was not of the essence unless expressly stipulated.

Therefore, where there was only a date for completion stipulated equity regarded

time as not of the essence. The party not in default had to serve a notice to

complete giving a reasonable time to complete before that party could terminate

the contract for breach: Canning v Tem by.

Courts of Equity did however recognise that in some cases, other than where

time is expressly of the essence, time could be impliedly of the essence in equity:

see Stickney v Keeble (1915) AC 386. That is where the surrounding

circumstances or the subject matter makes it imperative that the agreed date be

precisely observed.

The ascendancy of the equitable rule was statutorily affirmed by s 25(7) of the

Judicature Act 1873 (UK): see now Property Law Act 1974 (Qld) s 62.

Sub Element 2: Time not of the Essence

- If time is not of the essence failure to perform on time will merely be a breach of an

inessential term of the contract.

- Before the innocent party is able to terminate the contract it is necessary for the

innocent party to serve a notice to complete on the party in breach.

- The notice should give the party in breach a reasonable time to perform the obligation

before the innocent party is able to terminate the contract.

Time for giving notice to complete

Where Contract does not specify a date for completion

- There must be: o Failure to perform within a reasonable time

o The notice will then give a further reasonable time

Contract specifies a date for completion and time is not of the essence

- This will occur where: o The delay that extends beyond the date stated in the contract is so gross so

as to cause serious detriment to the other party.

o In a commercial contract where the delay is so unreasonable as to frustrate

the commercial purpose of the contract

- The notice to complete can be served immediately once the date of performance is

-

passed giving a further reasonable time for performance.

Failure to complete on that further date will be considered an unreasonable delay

allowing the innocent party to terminate.

Exception to the rule that a notice is required

- A right to terminate will arise for breach of a non-essential time stipulation without the

service of a notice where the delay is unreasonable: o Because of the serious consequences for the promisee, or

o Because the delay amounts to a repudiation of the party's obligations:

Laurinda v Capalaba Park shopping Centre.

Required content of the Notice

1. What the promisor must do to perform the contract

2. A reasonable time in which the contract should be completed; court will consider: - The nature of the transaction

- The remaining action$ a party is required to undertake to perform the contract

- How long the party has already been given to complete

3. A statement of the consequences of not performing in accordance with the notice

- Either that time is of the essence

- Or in the event of non-compliance the notifying party will regard itself as entitled

to terminate the contract Laurinda v Capalaba Park Shopping Centre

Element 7: Restrictions on the right to terminate

Sub element 1: Election

- A contract will not automatically terminate due to the breach of one of the parties it

must be terminated by one of the parties: Kelly v Desnoe.

- In general a party who has the right to terminate has a choice whether to affirm or to

terminate.

- If the innocent party elects to affirm the contract it will continue to subsist for the

benefit of both parties:

o Avery v Bowden

o Peter Turnbull Pty Ltd v Mundus Trading Pty Ltd.

- Reliance on a ground of termination, which proves untenable, does not prevent later

reliance on a then

- Existing ground which is adequate:

o Shepherd v Felt and Textiles of Australia Ltd (1931)

Sub Element 2: Further performance impossible

- Where further performance of the contract requires the co-operation of the other party

or is impossible, the innocent party may have no choice but to terminate the contract

for breach:

- White Et Carter (Councils) Ltd v McGregor

Sub element 3: Terminating Party not in breach

Dependent and concurrent obligations

- This will apply to the obligation to complete a land or sale of goods contract, which

are dependant and concurrent

- The terminating party must be able to show that they were ready, willing and able to

perform the contract at the time for performance. Foran v Wight

-

If the breach occurs at the time for performance of the contract the terminating party

must be ready willing and able at the time of performance.

o An innocent party who is not able to show they are ready willing and able

may not terminate the contract.

If the breach is prior to the time of performance, i.e. anticipatory breach, the terminating party

need only show that at the time of the anticipatory breach they were not wholly and financially

disabled from performing the contract. Foran v Wright

- Proof of this at the time of the anticipatory breach will enable the party to terminate

the contract

- However, if the party wishes to claim dama2es it will be necessary to show that they

would on the balance of probabilities have been ready willing and able on the date for

completion.

Obligations not Dependent and concurrent

- Where the obligations are not dependent and concurrent the terminating party does

not need to show they are ready, willing and able:

- Kelly v Desnoe

Sub Element 4: Terminating Party not in default

- Another restriction is that a terminating party cannot take advantage of their own

breach or default to terminate the contract or acquire a benefit under the contract:

Sub Element 5: Relief in Equity

Equitable Estoppel

See LWB136 notes on estoppel.

Relief against forfeiture:

Ct. exercising its equitable jurisdiction will prevent a vendor from relying on a forfeiture

clause. For the court to allow this remedy it requires: (Shiloh Spinners Ltd v Harding)

- That the object of the transaction and the insertion of a right to forfeit are essentially

to secure the payment of money.

- The party possesses a sufficient interest under the contract.

- The intervention of equity is appropriate, either because of unconscionable conduct

(exceptional circumstances) or because the forfeiture clause acts as a penalty.

The court will take into account when determining if exceptional circumstances exist:

- Whether vendor’s conduct contributed to the breach.

- How serious the breach was

- Whether the breach was wilful

- The damage actually caused to the vendor.

- The vendors’ gain weighed against the purchasers loss and whether an award of

specific performance is an adequate remedy for the vendor.

This remedy will usually not be granted where the failure to perform is a breach of an

essential time provision.

Sub Element 6: Right to terminate lost or excluded

- Right to terminate may be excluded by agreement, or legislation.

- The parties may expressly exclude the doctrine of repudiation.

- For example the contract may provide that the common law concept of repudiation

does not apply. It would be rare for a contract to expressly provide for this to occur.

However, the terms of the contract may provide for a code in relation to the

termination of the contract, which impliedly excludes the operation of the doctrine of

repudiation: Amann Aviation Pty Ltd v The Commonwealth (1990) 92 AlR 601.

Element 8: Effect of Discharge for Breach

Discharge of Obligations

- Both the party electing to discharge and the party in breach are released from all

future obligations under the contract. Some terms, however, intended to govern

liability for breach will continue to apply, eg arbitration clause, exemption clause,

limitation of damages clause.

Enforcement of accrued rights

- Unconditionally accrued rights, for example, fixed sums payable under the contract in

respect of performance rendered prior to breach, and causes of action which have

accrued because of a breach, are also unaffected by termination: McDonald v

Dennys Lascelles Ltd.

Recovery of Contract Price

- Contract price is only recoverable after termination if it has been earned prior to

termination. (Either exact or substantial performance)

- Will be able to claim completion of divisible parts if earned before termination.

- Defaulting party will not be able to resist a claim for payment on the basis of total

failure of consideration

Damages

Damages for breach of contract are awarded to compensate the person for their loss not to

penalise the wrongdoer

- Obligation to pay damages for failure to perform an obligation arises impliedly form

the entry into the contract.

o This is a secondary obligation assumed or agreed upon and not imposed

o Can be expressly excluded or limited

o Mere entry into contract is sufficient

Element 1: Is there a cause of action?

One of the parties fails to perform one or more of that party's obligations under the contract

Question of fact

Actual loss needs to be proved but proof of loss is not a precondition to damages

In the absence of actual loss nominal damages may be awarded

Onus of Proof

- Plaintiffs case on balance of probabilities

o Elements of cause of action

o Amount of loss suffered

o Causation

o Remoteness

- Defendants case

o Prove that plaintiff has failed to mitigate his loss

o If D does not argue above then it will be assumed P has mitigated loss

o Additional onus in cases where reliance loss is claimed Element 2: Causation

Did the wrong or breach of contract cause the loss?

Common law looks at whether: An act or omission contributed to the occurrence of a particular event (causation)

Responsibility should attach to that act or omission (remoteness)

Sub Element 1: the “But for” test.

- The traditional test for establishing causation in contract is the "but for" test.

- The loss would not have accrued but for the breach of the defendant.

- If the loss would have been suffered anyway no more than nominal damages will be

payable.

- It is not necessary that the D's conduct be the only factor as long as it's a cause of

the loss

Sub Element 2: Common sense approach and multiple causes

- Recognizes that the "but for' test is plainly inadequate where there are two separate

and independent events each of which alone was sufficient to cause the damage.

- Alexander v Cambridge Credit Corp the question should be; whether 'as a matter of

common sense, the relevant act or omission was a cause' of the loss.

- It is possible to apply the ‘but for’ test in a common sense way to determine whether

the breach ‘causally contributed’ to the damage.

- It is not necessary for the breach to be the only cause of the loss only that it was a

cause.

Sub Element 3; how causation can limit damages

Where the chain of causation between the defendant's conduct and the loss to the plaintiff

has been broken the defendant will not be liable for the loss.

Contributory Negligence

Where actions of the plaintiff contributed to the loss

In tort contributory negligence will not break the chain of causation but will reduce the amount

of damages

In contract, contributory negligence will only be relevant where the conduct is such as to

break the chain of causation between the defendant and the loss.

Lexmead (Basingstoke) Ltd v Lewis

- Farmer bought a towing hitch to connect his four wheel drive to a trailer

- Used it while broken for 3-6 months

- Trailer became loose and killed driver and son in a car

- Passenger brought action for damages for personal injury

- Farmer in 3rd party proceedings sought damages from seller of hutch claiming

breach of contract for goods no fit for purpose

Held:

- Loss arose from farmers negligence in not repairing hitch and not from seller so broke

chain of causation

Intervening acts or events

Action of 3rd party that is so substantial so it is no longer possible to conclude that the breach

of contract attributed to the loss

Intervening act must "act to supersede in potency" the breach of contract so that it can no

longer be considered as a cause either in common sense or in law

But where the D is under a contractual duty to guard against the very act of the intervener

there will be no break in causation e.g. writing a check in a careless way that allows someone

to change the payee

Where the intervening event is foreseeable by the parties this will not break the chain of

causation.

Mahoney v J Kruschich (Demolitions) Pty Ltd

- Causation may be broken by

o The relevant injury not reasonably foreseeable

o Chain of causation is broken by a noveus actus interveniens

o This is a Question of legal liability and not of fact

Monarch SS Co Ltd v AIB Karlshamns Oliefabriker

- Appellant breached its contract with the D to provide a seaworthy ship for the carriage

of cargo from Manchuria at o Sweden

- Vessel was delayed so couldn't reach Swede before WW2

- British ordered vessel to unload a Glasgow

- D had to arrange for cargo to be shipped to Sweden and Appellant was charged for

this cost

- Appellant argued that war intervened and broke chain of causation

- Held: appellant ought to have reasonably foreseen war might break out

Element 3: Is the loss suffered by the P not too remote?

- The law places a limit on the amount and time over which losses are recoverable

o A loss, which is causally related to the breach, will nonetheless not be

compensable if it is too remote.

- Remoteness operates as a policy factor in the courts decisions

o Remoteness of damage is governed by the rule in Hadley v Baxendale.

o Alderson- parties to a contract should only be liable for loss that could be

fairly and reasonably contemplated by both parties when making the contract.

o The principal is that damage is not too remote if it is such as may reasonably

be considered:

Sub element 1: First limb of Hadley V Baxendale

Damage that arises naturally according to the usual course of things from the breach will be

recoverable

- Court looks to the reasonable contemplation of a reasonable person on the position

of the parties to the contract.

- Alderson. The loss would be loss flowing naturally from the breach of the contract

in the great multitude of such cases occurring under ordinary circumstances

- Parties to a contract will have in their contemplation a result which will happen in

-

the great majority of cases (Koufos)

Test of reasonable foreseeability should not be applied to contract law (Koufos)

There have been several formulations of what is meant by the first limb of the rule:

Hadley v Baxendale

- In this case the 1st limb wasn't satisfied

- P, owner of a flour mill contracted with the D, a common carrier, to convey a broken

crankshaft to engineers to manufacture a new shaft

- Delivery was delayed so mill was stopped for 5 days longer and profit was lost

Held:

- D not liable for lost profits as he was a mere carrier who didn't know mill would be

stopped. Not a result that could have occurred in a multitude of cases

Koufos v Czarinkow

- 1st rule was satisfied

- D agreed to carry sugar form Constanza to Basrah but deviated taking 10 days

longer.

- Sugar prices fell in Basrah and P suffered loss of profit by selling at lower price

Held:

- Loss occurred in usual course of things because D knew

- P were sugar merchants

- There was a market for sugar in Basrah

Victoria Laundry Windsor Ltd v Newman Industries

- Part of the loss was recovered under the l' limb but the balance of the loss was too

remote

- P purchased a boiler from D to use in dye and dry cleaning business

- D damaged machinery while moving it and P refused to take it until fixed

- D delayed for 5 months

Held:

- D liable to P for an amount for loss of business in respect of reasonably expected

dyeing contracts- ordinary contracts

- But not for more lucrative contracts

Notes

- In Koufos v Czarinkow Ltd the House of Lord unanimously considered a test of

reasonable foreseeability was not appropriate to contract.

- Burns v MAN Automotive (Aust) Pty Ltd at 667 i.e. what is the loss that is "sufficiently

likely to result".

- H Parsons Livestock Ltd v Uttley Ingham & Co It is only necessary to foresee the

type of damage, not necessarily the degree of damage that would result from the

breach:

Sub element 2: Second limb of Hadley v Baxendale

- A plaintiff who claims loss not arising in the usual course of things must come within

the second limb if the loss is to be recovered- This limb relies on actual knowledge possessed by the defendant.

o The basis of this rule is said to be that the defendant with actual knowledge

of special facts is undertaking to bear a greater loss: Koufos v Czarinkow Ltd.

- In addition to actual knowledge of the special circumstances it is necessary for the

defendant to either

o Acquire this knowledge from the P, or

o For the P to know the D is possessed of the knowledge at the time the

contract is entered into, and so could reasonably foresee that an enhanced

loss was liable to result from a breach.

- Only a loss that is likely to occur in a majority of cases will not be too remote

McRae v Commonwealth

- An example of damage that falls within the second limb

- D had warranted to P that a tanker lay on a coral reef and needed salvage

- P expended moneys to locate vessel which wasn't where D said

- Held: expenditure fell within the 2"' limb because of the D's actual knowledge of the

need for a salvage operation

Contrast with Victoria Laundry {Windsor Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd

- Even though D had knowledge of the business of the p and the fact that the p wanted

to put boiler into immediate operation, this wasn't sufficient to bring knowledge into

second limb

- D did not have actual knowledge of the specific contracts p had entered into

Sub Element 3: What is the extent of loss that can be recovered

Exactly what must the parties contemplate?

H Parsons (Livestock) Ltd v Uttley Ingham & Co

- P's pigs died as a result of eating contaminate nuts from a faulty hopper bought from

D. The loss had been caused by the negligence or breach of contract of D

- Although' it couldn't be considered that the parties would have contemplated the

death of the pigs as a probable result, ct held D was liable for loss of pigs

o Majority considered that as p was suing for breach of an implied term, that

hopper would be fit for purpose, the question was whether the parties

considered that breach of an implied term would lead to loss of pigs

o Parties should have considered that if the hopper was not suitable for storage

of pigs nuts then it was a serious possibility that the pigs would become ill

o Accordingly the parties need only contemplate the type of injury that has

occurred not the full extent of the loss

- Lord Denning: in cases of physical damage forma breach of contract the test applied

should be one of reasonable foreseeability and not reasonable contemplation

Element 4: Has the P acted reasonably to mitigate unnecessary loss?

- The general rule is that a plaintiff should mitigate his/her loss.

- The plaintiff is not entitled to claim for loss, which the plaintiff could have avoided by

taking reasonable steps: Dunkirk Colliery Co v Lever

- The onus of proving the plaintiff acted unreasonably is on the defendant.

Sub Element 1: Has the P Acted reasonably

- P is only required to take those steps. Which are reasonable and is not required to resort

to steps. Which are costly or extravagant:

- Whether the p has acted reasonably or unreasonably is a matter of fact and will depend

on the individual circumstances of the case.

o As long as P's have acted reasonably they should not be debarred from

recovering actual loss because D can show that if p had taken another course,

the loss would have been lower

o Likewise if P's loss diminished s a result of its actions, this must be taken into

account

British Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co Ltd v Underground

Electric Railways Co of London Ltd

Sub Element 2: Should the P enter into a further contract with D

If the parties had the opportunity of entering into a new bargain after breach, which might

have eliminated the loss suffered, the issue is whether the plaintiff has acted reasonably in

refusing to enter into a new contract:

Commercial Contracts

- Where the D makes a reasonable offer to resume the contract, it should generally be

accepted by the p

- Question is whether the refusal is reasonable

o

o

Where the new contract may cause risk to P, refusal may be reasonable

Refusal to negotiate because of any ulterior motive may also deny the

plaintiff any damages

Employment Contracts

Overriding consideration is whether the refusal is reasonable. It may be reasonable where: - The new offer of employment is at a lower status

- The new offer of employment requires the p to abandon his legal rights arising from

the breach

- The new offer of employment is made during the course of proceedings to claim

damages where the offer is made to reduce the damages awarded

Sub Element 3: should the P purchase a substitute in the marketplace?

In the ordinary course, an injured party would attempt to avoid loss by making a substitute

arrangement

Sub Element 4: Reductions or Increases In the amount of loss

Increase in loss

- The mere fact the loss of the p has increased will not bar the p from recovering the

loss from the D.

- If the p has acted reasonably then the loss may be recoverable: Banco de Portugal v

Waterlow & Sons Ltd

Decrease in loss

- Where the p obtains extra benefits as the result of the breach of the D then these

benefits must be accounted for in assessing the damages.

- For example where an employee is unfairly dismissed the damages payable will be

reduced by the amount earned from another employer after the dismissal: Lavarack v

Woods of Colchester Ltd

- Or the advantage of newer and more efficient machinery purchased to replace

defective machinery may have to be taken into account: British Westinghouse

Electric and Manufacturing Co Ltd v Underground Electric Railways Co of London

Ltd.

Sub Element 5: Limitations on the mitigation principles

Anticipatory breach and mitigation

- No question of mitigation can arise until there is an actual breach of contract or an

anticipatory breach that is accepted as repudiation

o In most cases the innocent party should consider mitigation prior to

termination of the agreement.

- The exception occurs in the case of anticipatory breach where there is no breach

until such time as the breach is accepted and the contract terminated.

o Where repudiation precedes the time for performance, there can be no issue

of mitigation until termination has taken place: White and Carter (Councils)

Ltd v McGregor.

- The mitigation principles do not apply unless the plaintiff's claim is for damages as

distinct from an action for a debt or a liquidated sum: White and Carter (Councils) Ltd

v McGregor.

Element 5: Assessment of Damages

Principle in Robinson v Harman

- Where a party sustains a loss by reason of a breach of contract, the party is, so far

as money can do it, to be placed in the same position as if the contract had been

performed.

o The P will be awarded damages commensurate with the loss of expectation

or profits from the contract

- In a contract for sale of goods or land the general measure of the loss of expectation

is the difference between the contract price and the market value of the Roods or

-

-

land at the time of breach.

In other cases where the breach has prevented the opportunity to earn the

expectation or profits from arising, the court will have to estimate the value of the

potential expectancy.

Fact that damages are difficult to calculate is not a bar to recovery

Date of Assessment

- Damages are usually assessed at the date of the breach. However, the date may be

altered so a Pl gets the amount that most fairly compensates them.

Johnson v Agnew

- Where a debt is payable in a foreign currency- date when the debt should have been

paid

- A sale of goods for which there is no available market- reasonable time after the

breach

- Cases of anticipatory breach- date for the performance of the contract

- Court assess the damages once and for all and as per a particular date therefore it

takes into account

o Market value at the date

o Whether the loss is capable of mitigation

- Events that occur after the date of the breach are irrelevant unless

o The p gets a benefit that would not have occurred but for the breach.

o Loss of an income earning asset occurs

Sub Element 2: Once and for All Rule

- Court assess the damages once and for all and there is a lump sum payment

- There is no right to return to court to recover additional loss accrued at a later date

unless:

o There is more than one cause of action

o There is a continuing breach

- In each of these cases the court will award damages for the loss sustained at the

date of trial and any additional loss may be recovered in a further action

Sub Element 3: Net Loss only recoverable

- Court takes into account any benefits or saved expenses received by the p as a

result of the breach due to:

o Contract has been prematurely terminated

o Due to the acts of the p to mitigate the loss

- P should not be placed in a better position as a result of the breach

- Court therefore takes into account: o The value of any asset in the hands of the p- if p retains any asset he has

purchased, ct takes into account the residual value of assets. Cth v Amann

Aviation Pty Ltd

Sub Element 4: Expectation of loss

- The value of the expectancy that the promise created.

- This can be compensated in a suit for specific performance or by making the guilty

party pay the money value of the promise (usually equated with loss of profits)

- As damages for breach of contract are designed to place the injured party so far as

money can do it in the same situation as if the contract had been performed, they are

normally assessed on the basis of expectation loss or loss of profits.

- Loss of profit or value

o Difference between the contract price and the value of the subject matter of

the contract at the date of the breach

o Applies inc contracts for sale of real property and sale of goods

- Loss of opportunity

- Cost of rectification of defective work

- Delay in the payment of money

Sub element 5; Reliance loss

- Where one party in reliance on the promise of another expends money (eg purchaser

-

-

of land expends money on investigating the title).

The object of reliance loss is to put the innocent party in the same position he/she

was in before he/she entered into the contract.

Damages for breach of contract are not usually calculated on the basis of reliance

loss (expenditure) but in some cases calculation of damages on the basis of

expectation does not adequately reflect the loss of the plaintiff.

As a general rule damages may be recoverable on the basis of reliance loss where:

o There is no way of quantifying the expectation loss; or

o No profit will be made on the contract

Losing Contracts

- Reliance loss is not available if the defendant can prove the plaintiff had entered into

a losing contract and would not have been able to recoup the expenditure even if the

defendant had performed all his/her obligations.

- The plaintiff may however. Be able to recover some amount for wasted expenditure

- The Commonwealth v Amann Aviation (this is an example of where no profit was

going to be made on the contract). It also discusses the proviso relating to losing

contracts (see below for losing contracts).

Sub element 6: Recovery of both reliance and expectation loss

Anglia Television Ltd v Reed

- It was suggested that a plaintiff cannot pursue a claim for both expenditure (reliance

loss) and loss of profits (expectation loss) as this would lead to double recovery and

the Plaintiff would be in a better position than if the contract had been performed

- The preferable view is that lost expenditure and expectation loss are both

recoverable where the lost expenditure forms part of the profit expected to be made

by performing the contract. - Gates v City Mutual Life Assurance Society Ltd

Sub Element 7: Kind of Damages

Damages may be recovered for - Physical injury caused by breach of contract: Cullen v Trappell .

- Disappointment: Jarvis v Swan Tours but not for injured feelings: Addis v

Gramophone Co Ltd

- Mental distress: Baltic Shipping v Dillon.

- Delay in performance. This now extends to delay in the payment of money:

Hungerford’s v Walker.

- Lost opportunity: Commonwealth v Amman Aviation Pty Ltd

- The Court also has a discretion to award interest on damages under the Common

Law Practice Act 1867, ss 72, 73.

Sub Element 8: Issues impacting on the recover of damages

- Is termination of the K required

- Should the P be ready willing and able to perform

- Is accrued right to damages lost after termination or breach

- Does affirmation of a K waive damages for breach

Sub Element 9: Agreed Damages Clauses

- The contracting parties may agree what sum shall be payable by way of damages in

the event of breach.

- If the sum so fixed is a genuine pre-estimate of loss, it will be accepted by the court

and awarded

o As "liquidated damages".

A liquidated sum is also referred to as a debt.

The main advantage in seeking to recover a debt as opposed to

damages is that a plaintiff does not have to prove the amount of the

debt. Unlike a claim for damages, the plaintiff is entitled to seek the

amount specified in the contract irrespective of any loss suffered.

-

-

Where the sum fixed by the contract bears little relationship to the loss incurred, that

clause of the contract may be struck down as being a penalty.

Factors the court takes into account in determining whether a particular clause is a

penalty, include:

o The bargaining power of the parties;

o The intention of the parties;

o Whether the stipulated sum is clearly in excess of the greatest possible loss

that might be expected to follow from the breach;

o The presumption that the stipulated sum is a penalty if it is payable on the

occurrence of one or more of several events, some of which will result in

serious, and others in only trifling damage.

However, genuine pre-estimates stipulated in the contract make it unlikely to be

considered a penalty.

Where a damages clause is struck down for being a penalty, the innocent party will

be left to prove their loss in the normal way.

Restitution

Element 1: Introduction

The principle of unjust enrichment involves three things:

1. The defendant has been enriched by the receipt of a benefit;

2. The defendant has been enriched at the expense of the plaintiff; and

3. It would be unjust to allow the defendant to retain the benefit.

Element 2: Recovery by the party not in breach

Money

- The injured party is entitled to recover sums paid for which there has been a total

failure of consideration.

- Alternatively, he or she may claim damages (any award taking into account any

prepaid sum which has not been recovered).

- It is not possible to claim both restitution and damages:

o Rowland v Divall

o Fibrosa v Fairbairn

o Baltic Shipping v Dillon (1993) 67 ALJR 228 at 230-236.

Services

- Where an injured party, who has performed work for the party in breach, elects to

discharge for breach, the injured party may, as an alternative to a damages claim,

claim on a quantum meruit for the value of the work done (a quasi-contractual claim).

- This form of relief will be particularly relevant where the effect of the breach prevents

further performance by the injured party:

- Planche v Colburn

- Automatic Fire Sprinklers v Watson.

- Also where the contract is unenforceable because of a statutory provision requiring

the contract to be in writing, the party who has completed the contract may be able to

claim on a quantum meruit for work done: Pavey v Matthews Pty Ltd v Paul (1987)

162 CLR 221

Element 3: Recovery by the party in breach

Money

- The party in breach is entitled to recover any part payments of the contract price for

which no consideration has been received.

- The party in breach is not, however, entitled to the return of a pre-paid "deposit" (as

sum paid as an earnest or guarantee of due performance, commonly 10 per cent or

less of the contract price), or any other payment, which is forfeited pursuant to a

provision (express or implied) in the contract: McDonald v Dennys Lascelles.

- Note, however, the existence of an equitable power to relieve against forfeiture, that

is, where the agreed contractual provision forfeiting the payment is in the nature of a

penalty and it would be "unconscionable" for the other contracting party to retain the

money:

o Pitt v Curotta (1931) 31 SR (NSW) 477

o McDonald v Dennys Lascelles (1933) 48 CLR 457.

Services and goods

- The party in breach is generally not entitled to a restitutionary claim unless the other

party has freely accepted the goods or performance of the services by the other party

or converted the services or goods into money in their hands. Steele v Tardiani

- In each of the above cases, the party in breach will be able to say that the other party

has received a benefit, which it is unjust to retain unless payment is made

Equitable Remedies

1. Introduction

Under specific circumstances, a promise to do a thing may be enforced by an order for

specific performance and an express or implied promise to forbear by an injunction.

These remedies are equitable remedies and are therefore discretionary. They will not

normally be granted if the common law remedy of damages is adequate in the

circumstances.

2. Specific performance

This is an equitable remedy by which a court orders a defendant to perform the contractual

obligations. Its main application is in the case of contracts for the dale or other disposition of

land.

However, by s 53 Sale of Goods Act 1896 (Qld) the court may, if it thinks fit, direct that a

contract for the sale of goods be specifically performed. Such order will not be made except

where the chattel sold is unique in some way. In some way, an order to pay an agreed sum of

money may be obtained; Berwick v Berwick [1968] AC 58.

3. Injunction

This is also an equitable remedy. It is dealt with in more detail in the Equity course. It will be a

particularly effective remedy where the plaintiff seeks to prevent breach by the defendant of

an express negative promise (a promise not to do something), eg breach of an enforceable

"restraint on trade" clause:

Lumley v Wagner (1852) 1 De GM&G 604; and

Warner Bros v Nelson [1937] 1 KB 209.

Limitations of Actions

1. Common law

In Queensland, the period within which an action founded on simple contract must be brought

is six years from the date upon which the cause of action arose (s 10(1)(a) Limitation of

Actions Act 1974). A court will dismiss an action brought outside of this time period.

The cause of action accrues on the date the breach of contract is committed: Ward v Lewis

(1896) 22 VLR 410.

2. Exceptions to the rule

a. Where a cause of action is based on fraud or for relief from the consequences of mistake,

the period of time before the aggrieved party discovers (or any have with reasonable

diligence discovered) the fraud or mistake is not included within the six year time period

(s 38).

b. Where a person is under a disability (eg an infant or a person of unsound mind) at the date

on which a right of action accrues, the limitation period is extended for a period of six

years from the date on which that person ceases to be under a disability (s 29(2), (3)).

3. Equity

The courts exercising their equitable jurisdiction are not bound by the time limitations

imposed for actions under the common law in the limitations of actions act. However, the

courts exercising their equitable jurisdiction will only hear a case if it is brought within a

reasonable time – a maxim of equity is that “Equity favours the diligent not the tardy”. This

may mean that an action in equity may expire faster than one under the common law

depending on its nature.

S.43 of the LAA 1974 provides the act does not affect the rules of equity concerning the

refusal on the grounds of acquiescence or otherwise.

Misrepresentation

Element 1: Definition

It is a false statement of existing or past fact, which is addressed to the representee, before

or at the time when the contract was made; and which was intended to and did induce the

representee to make the contract.

Element 2: A false statement of existing or past fact

- The statement need not be made in writing; a misrepresentation can be made by

means of conduct. Waiters v Morgan

- However, a representation of fact must be distinguished from:

Sub Element 1: A representation of law

- One can only ever express an opinion as to the law on an issue until a court

adjudicates on it.