The Bases of Attachment

advertisement

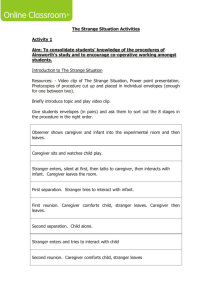

ATTACHMENT Covered in Ch. 6, Sroufe Another approach to consistency in early behavior is the study of attachment – an emotional bond between caregivers and infants. Bowlby (British infant psychiatrist, object relations approach, supervised by Melanie Klein, influenced by evolutionary theory) – was interested in the study of the effects of parental loss in infants. Observed that an attachment relationship forms for all but the most extreme cases. Retarded infants become attached, but at a later age. Blind infants do too, but show behavioral differences. Abused infants attach too. Only institutionalized infants, who do not have a single caregiver do not show attachment. Harlow’s monkey studies – surrogate-raised monkeys who had offspring as adults were rejecting and punitive parents. Even so, infants showed anxious attachments (clinging). Sought to identify individual differences in the quality or particular nature of the attachment. His major hypothesis was that attachment is based on the quality of care. If care is consistent, if the caregiver responds to signals of need, alleviating stress, and there is communication, a secure attachment relationship will develop. Even if not, infants are robust and some form of attachment will form anyway. Attachment – an enduring emotional tie between child and caregiver. Evident in separation distress as well as in apparent security derived from caregiver’s presence. By 12 months, child wants to picked up specifically by caregiver, and seeks out caregiver when upset, and explores in caregiver’s presence. Hallmarks of Attachment Preattachment phase (0 to 6 weeks) – Infant behaviors elicit adult response. Ability to be comforted by being picked up and held, stroked, rocked. Babies can recognize mother’s voice and smell. No attachment yet. Attachment-in-the-making phase (6 weeks to 6-8 months) – differential responses to a familiar caregiver. Child at 4 months will laugh, smile and babble more freely with familiar person, and will be comforted more easily. Beginning recognition of parent as individual, but no separation anxiety yet. “Clearcut” attachment (6-8 months to 18 months-2 years) – Separation distress – present in all cultures by end of first year, but depends on degree of caregiver-child contact. Occurs universally, appearing after 6 mo. And increasing until about 15 months. Also seen in older infants and toddlers trying to maintain mothers presence. Approach, follow, and climb on mother in preference to others. Mother used as a secure base for exploration. Secure-base behavior – pattern of exploration. Explore more confidently when caregiver is present and check with caregiver frequently. Return to caregiver when threatened. Formation of a reciprocal relationship (18 months – 2 years and on) – Growth of representation and language permits toddlers to begin to understand the parent’s coming and going and to predict her return. Separation protest declines. Start of negotiation with caregiver, using requests and persuasion.. Greeting reactions – immediate joyful response on seeing caregiver. The Bases of Attachment (Distinct from bonding – parent’s tie to newborn during first few hours.) Major hypothesis: attachment is based on the quality of care. If care is consistent, if the caregiver responds to signals of need, alleviating stress, and there is communication, a secure attachment relationship will develop. Even if not, infants are robust and some form of attachment will form anyway. Child forms an internal working model, or set of expectations about the availability of attachment figures and their likelihood of providing support during times of stress. Will occur with any consistent caregiver, and may occur with more than one caregiver. Measuring attachment: Mary Ainsworth – devised the strange situations test to be done in home or lab playroom. A series of situations in which the child and mother enter, the child is allowed to explore, followed by a sequence of a stranger entering and the mother leaving. How the child responds to the stranger and to the mother’s return is observed. The Ainsworth Strange Situation Episode 1 Participants Mother, infant Duration Brief Content A mother and her child enter the room. The mother places the baby on the floor, surrounded by toys, and goes to sit at the opposite end of the room. 2 Mother, infant 3 min. Mother sits in a chair while baby plays with toys. 3 Mother, infant, stranger 3 min. A female stranger enters the room, sits quietly for a minute, converses with the mother for a minute, and then attempts to engage the baby in play with a toy. 4 Infant, stranger 3 min. (or less) The mother leaves the room unobtrusively (first separation). If the baby is not upset, the stranger returns to sitting quietly. If the baby is upset, the stranger tries to soothe him or her. 5 Mother, infant 3 min. The mother returns (first reunion) and engages the baby in play while the stranger slips out of the room. 6 Infant 3 min. (or less) The mother leaves again (second separation), this time leaving the baby alone in the room. 7 Infant, stranger 3 min. (or less) The stranger returns. If the baby is upset, the stranger tries to comfort him or her. 8 Mother, infant 3 min. The mother returns (second reunion) and the stranger slips out of the room. Patterns of Attachment Secure attachment (70% of all relationships) A. Care giver is a secure base for exploration 1. readily separate to explore toys 2. affective sharing of play 3. affiliative to stranger in mother's presence 4. readily comforted when distressed (promoting a return to play) B. Active in seeking contact or interaction upon reunion 1.if distressed a. immediately seek and maintain contact b. contact is effective in terminating distress 2.if not distressed a. active greeting behavior (happy to see care giver) b. Strong initiation of interaction Anxious resistant attachment A. Poverty of exploration 1. difficulty separating to explore, may need contact even prior to separation 2. wary of novel situations and people B. Difficulty settling upon reunion 1. may mix contact seeking with contact resistance (hitting, kicking, squirming, rejecting toys) 2. may simply continue to cry and fuss 3. may show striking passivity Anxious avoidant attachment A. Independent exploration 1. readily separate to explore during pre-separation 2. little affective sharing 3. affiliative to stranger, when care giver absent (little preference) B. Active avoidance upon reunion 1. turning away, looking away, moving away, ignoring 2. may mix avoidance with proximity 3. avoidance more extreme on second reunion 4. no avoidance of stranger SOURCE: Adapted from Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, and Wall, 1978. Another category was defined by Mary Main – disorganized-disoriented. Children show contradictory features of various patterns or appear dazed or disoriented. Movements may be incomplete or very slow, or they may become motionless or depressed. No consistent way of relating to the care giver when they are stressed, presumably because of some persistent threat or incoherence in the care giver’s behavior. Cultural variations – Social class differences – middle-SES families with stable life conditions generally show stable secure attachment. Low-SES families with many daily stresses show more unstable patterns. Also true for families undergoing major life changes – change in employment, or divorce. German infants show more avoidant attachment than Americans. Discourage clingy behavior and encourage independence more. Japanese infants, who experience almost no separation from parents, become extremely upset in the Strange situation. Show more resistant response. Japanese mothers rarely leave child in care of someone else, so they may react with more stress to the Strange Situation. Quality of care and security of attachment 1. 2. 3. 4. opportunity to establish a close relationship quality of caregiving baby’s characteristics family context in which infant and parent live. Opportunity to establish a close relationship Rene Spitz and the failure to thrive of institutionalized infants. Long-term effects – through childhood and adolescence, show more emotional and social problems, including and excessive desire for adult attention, “over friendliness” to unfamiliar adults and peers, few friendships. Quality of Caregiving Comparison of maltreated children with non-maltreated – more anxious attachments in the maltreated groups. Extreme poverty and physical neglect have been associated with an increase in resistant attachment, while avoidant attachment is predicted by physical abuse and “emotional unavailability”. In the latter, all infants showed avoidant attachment by 18 months. Also related to the disorganized category. Sensitive care (responding to babies cries and other signals) associated with secure attachment. (note contrary prediction by the behaviorists). Anxious-resistant attachment associated with inconsistent care. Exaggerated behaviors by the mother and ineffective soothing (overstimulation) predicted resistant attachment, while rejection of physical contact predicted avoidant attachment. Infant Characteristics. Temperament – proneness to fear and irritability or distress is moderately associated with later insecure attachment. Probably related to mothers. Distress-prone infants who becames insecurely attached tended to have rigid, controlling mothers. The context of caregiving Life stress and social support - financial and work pressure. Can cause anxious attachment. Parental developmental history – Seems to be a predictive relationship between type of care (responsiveness) and attachment with own children. Self-reports are difficult to validate. Animal studies suggest that amount of contact is predictive of own mothering behavior. Infant attachment and later development Bowlby suggested that different patterns of attachment reflect differences in the infants’ expectations or internal working models of the social world. @An infant who has experienced reliable, responsive care, and who is secure in his or her attachment, has begun to develop a model of the care giver as available and, at the same time, of the self as worthy of care and as effective in obtaining care. These attitudes and representations are carried forward and influence later experience, Attachment relations do seem to predict how children will do later. Curiosity, enthusiasm in solving problems, high self-esteem, and positive relations with teachers and peers have all been found to be strongly linked to the quality of early attachments. Attachment patterns in adult behavior The inner feelings of affection and security that result from a healthy attachment relationship support all aspects of psychological development. Securely attached infants tend to be higher in self-esteem, more socially competent, cooperative and popular. Avoidantly attached children viewed as isolated and disconnected, and resistantly attached regarded as disruptive and difficult. Adult attachment can be measured through self-report scales where people classify themselves as secure, avoidant, or ambivalent. Secure adults described their most important love relationship as more happy, friendly, and trusting, compared with the other two groups. Relationships also had lasted longer. Avoidant adults were less likely than the others to report accepting their lovers’ imperfections. Ambivalents experienced love as an obsessive pre-occupation, with a desire for reciprocation and union, extreme emotional highs and lows, and extremes of both sexual attraction and jealousy. Also more likely than others to report that the relationship had been love at first sight. Ambivalent college students are most likely to have obsessive and dependent love relationships. Avoidants are the least likely group to report being in love either presently or in the past. Secure persons show the most interdependence, commitment, and trust. Other reflections: Orientations to work: Ambivalents report unhappiness with the recognition they get from others at work and with their degree of job security. Also most likely to say their work is motivated by a desire for approval from others. Involves lack of closeness. Therefore their involvement in work may be a means of escaping from lack of relationships. Responses to stress: Among secure individuals, stress led to making contact and both getting and providing reassurance. Among avoidant subjects, stress led to a shutting down of contact on both sides. Interpersonal relations: Secure partners are most desired and tend to wind up with each other. Less satisfaction when man is avoidant and woman is ambivalent. However, avoidant men with ambivalent women tend to be stable pairings, despite dissatisfactions. Avoidant men avoid conflict, while ambivalent women try to hold things together. Avoidants with avoidants and ambivalents with ambivalents are rare, suggesting that people with insecure attachment patterns steer away from partners who would treat them as they were treated in infancy. Avoidants avoid partners who will be emotionally inaccessible, and ambivalents avoid partners who will be inconsistent.