Does togetherness make friends

advertisement

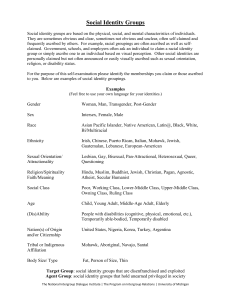

Does togetherness make friends? Stereotypes and intergroup contact on multiethnic-crewed ships. Dorte Østreng1 Abstract: This paper explores the construction and maintenance of distance and social boundaries on multiethnic-crewed ships. Ethnic and national stereotypes are frequently used to explain conflicts, communication problems and the segregated social life among sailors of different national, ethnic and cultural groups. The main object of this paper is not to discuss how and why stereotypes are made and used in the first place, but why sailors continue to hold stereotypical attitudes when they are working and living together on the same ship for several months. The analysis in this paper shed light on working relations and stereotypical attitudes among Norwegian and Filipino sailors as an empirical case. By exploring the contact hypothesis this paper discusses why togetherness does not necessarily generate friendships across national, ethnic and cultural boundaries, why intergroup hostility and tension are maintained, and why contact does not lead to changes in stereotypical attitudes. This paper is originally prepared for the dr.polit course ’Comparative Cultural Sociology’ lectured by Professor Michèle Lamont, Oslo Summer School in Comparative Social Science 2000, University of Oslo. The paper has been written as part of my doctoral research project in Sociology ’Interethnic communication among sailors’. I thank Grete Brochmann, Pål Meland, Christin Berg, Jon Reiersen and Are Branstad for helpful and valuable comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Correspondence: Vestfold College, Department of Maritime Studies, P.O. Box 2243, N-3103 Tønsberg, Norway, or e-mail to Dorte.Ostreng@hive.no 1 Does togetherness make friends? 2 ”The subtlest and most pervasive of all influences are those which create and maintain the repertory of stereotypes. We are told about the world before we see it”. Walter Lippmann (1922: 89-90) “If unacquainted with the individual, observers can glean clues from his conduct and appearance which allow them to apply their previous experience with individuals roughly similar to the one before them or, more important, to apply untested stereotypes to him”. Erving Goffman (1959:13) Introduction Over the last decades, researchers in the social sciences have been concerned about the relationship between social stereotypes and intergroup contact. Despite intensive research2 there is still no clear consensus on how to improve intergroup relations and attitudes through intergroup contact. However, it is quite often assumed that intergroup contact and interaction plays an important role in the reduction of intergroup hostility and the elimination of stereotypes, but intergroup contact could just as much lead to increased tension between ingroups and out-groups. This paper explores the relationship between stereotypes and intergroup contact on multiethnic-crewed ships. The crew of a ship constitutes a small group and is clearly demarcated from the world around it. The question of how the group is integrated and the extent to which the members are dependent upon one another is therefore an interesting object of study. Research about the ship as a multiethnic workplace, describes a segregated social environment, with distinct boundaries and stereotypical attitudes among sailors from different national, ethnic and cultural groups. One might assume that sailors who are working and living together in an isolated and closed social system over a long period of time would generate friendships and eliminate intergroup tension and hostility. However, this doesn’t seem to be the case. By examining the contact hypothesis I will discuss how intergroup contact might lead to decategorization and improved intergroup relations, and more importantly why togetherness does not necessarily create friendships through discussing characteristics of the contact situation and the interacting groups by viewing multiethniccrewed ships as a case3. The main aim of the paper then, is to discuss why contact among sailors from different national, ethnic and cultural groups does not lead to unity and reduction 2 Mostly in Social Psychology. I am writing this paper in an early stage of my doctoral research project. I have therefore not yet been able to collect data for this project, and must therefore base my analysis in this paper on data selected by other researchers. I am planning to do fieldwork during spring and summer of 2001. The empirical descriptions and analysis in this paper are therefore based on current research literature about multiethnic-crewed ships. However, there is not much research done recently in this field, and most of the literature presents several key topics in a highly superficial way. One of the exceptions though, is an ethnographical research project done by Christoffer Serck-Hanssen (1996, 1997a, 1997b) on two cargo ships crewed exclusively by Norwegians and Filipinos. 3 Does togetherness make friends? 3 of intergroup tension and categorisations. In order to do this I will first define social stereotypes and describe the process of stereotyping, by focusing on the social identity theory. I will then describe distinctions and stereotypes between sailors of different national origin. I will further discuss the relation between stereotypes and intergroup contact and the process of decategorization and the contact hypothesis, but most important I will take into consideration characteristics of the contact situation and the interacting groups. Contact situations among sailors of different nationalities will be used as a case for explaining why togetherness does not necessarily make friends. Social stereotypes and the process of stereotyping Social identity theory Several researchers have examined the tendency for human beings to differentiate themselves according to group membership. The sociologist William Graham Sumner has documented this through careful observations (Sumner 1906), and is known for adopting the terms ingroup and out-group to refer to social groupings to which a particular individual belongs or does not belong, respectively. Sumner used the term ethnocentrism about attachment to ingroups, and the preference of in-groups over out-groups. “A differentiation arises between ourselves, the we-group, or in-group, and everybody else, or the others-groups, out-groups. The insiders in a we-group are in a relation of peace, order, law, government, and industry, to each other… Ethnocentrism is the technical name for this view of things in which one’s own group is the centre of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with preference to it… Each group nourishes its own pride and vanity, boasts itself superior, exalts its own divinities, and looks with contempt on outsiders.” (Sumner 1906: 12-13) The social identity theory (Tajfel 1986) holds that an individual’s personal identity partly is based on membership in significant social categories. In a given situation, or when a particular social category distinction is highly relevant, the individual will respond with respect to that aspect of his social identity, acting towards others in terms of their corresponding group membership rather than his personal identity (Brewer & Miller 1984). The theory (for further readings, Hinton 2000; Tajfel 1978, 1981; Tajfel & Turner 1986; Brewer & Miller 1984, 1996) assumes that people are motivated to evaluate themselves positively, and that insofar as a group membership becomes significant to their self-definition they will be motivated to evaluate that group positively. In other words, people seek a positive social identity. Since the value of any group membership depends upon comparison with Does togetherness make friends? 4 other relevant groups, positive social identity is achieved through the establishment of positive distinctiveness of the in-group from relevant out-groups. According to Sumner’s analysis, the essential characteristics of an individual’s relationship to in-groups are loyalty and preference (Brewer & Miller 1996). Loyalty is presented in adherence to in-group norms and trustworthiness in dealing with fellow in-group members. Preference is represented in differential acceptance of in-group members over members of out-groups, and positive evaluation of in-group characteristics that differ from those of out-groups. Personal identity refers to self-conceptualisations that define the individual in comparison to other individuals. Social identities refer to conceptualisations of the self that derive from membership in emotionally significant social categories or groups. Personal identity and social identity are mutually exclusive levels of self-definition. Social identities are categorisations of the self into more inclusive social units that depersonalise the self-representation. Depersonalisation does not, according to Brewer and Miller (1996), mean a loss of individual identity, but rather a change from the personal to the social level of identity. Individuals are likely to think of themselves as having characteristics that are representative of that social category. In other words, social identity leads to selfcategorisation or self-stereotyping. A primary consequence of such categorisation is the depersonalisation of members of the out-group categories (Brewer & Miller 1984). There is a tendency to treat individual members of the out-group as undifferentiated items in a unified social category, independent of individual differences that may exist within groups, and independent also of any personal relationships that may exist between members of the two groups in other situations. As further described below, this is the process of stereotyping. What are social stereotypes? There seems to be a general agreement among social scientists as to the key features of a stereotype. Due to Hinton (2000) a stereotype has essentially three important components. First, there is a group of people identified by a specific characteristic, which could be anything from nationality, ethnicity, gender or occupation. By identifying the group on this characteristic we are able to distinguish them from other groups. Second, we attribute a set of additional characteristics to the group as a whole. These characteristics are usually personality characteristics, but could include physical characteristics as well. The important is the attribution of these additional characteristics to all members of the group, and finally, on identifying one person as having these characteristics we attribute the stereotypical characteristic to him. Stereotyping is then the process of ascribing characteristics to people on Does togetherness make friends? 5 the basis of their group memberships. The stereotypes of one group shared by members of another group are usually referred to as social stereotypes (Tajfel 1981). Stereotypes are shaped by group memberships and are a product of intergroup relations. In holding stereotypical attitudes we make boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’. The contents of stereotypes are due to that commonly constructed as binary oppositions, like ‘black/white’, ‘masculine/feminine’, ‘tall/short’ or ‘aggressive/emotional’. When two groups are contrasting, or making distinct boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’, the less favourable characteristics are used to describe the out-group and the preferable opposition is used to identify themselves with the in-group. Defining what the in-group is also requires defining what it is not. In that sense in-groups require out-groups (Brewer and Miller 1996). Distinctions and stereotypes among sailors The empirical case being discussed in this paper is multiethnic-crewed ships owned and registered in Norway but sailing in international trade4. The Norwegian ship owners differ in their policy in how many different ethnic groups they mix on each ship, and also from which countries they recruit the crew. In 1999 the number of sailors on Norwegian ships in international trade was 66 250 in total. Of those, 15 100 were Norwegians and 51 150 were recruited from other nations (The Norwegian Shipowners Association 1999). The Norwegians are exclusively officers and never among the able seamen aboard these ships. Most of the foreigners are recruited from the Philippines, India, Poland and Russia, which are all poor countries where the salaries can be kept low. 60% of the foreigners are recruited from the Philippines. The social environment on ships is in many ways quite unique compared to other workplaces on shore. The organisational structure is highly hierarchic, based on military principles. The responsibilities and tasks are clearly defined, and the communication is based on commands. The hierarchic organisational structure is quite visible through symbolic boundaries and structural distinctions among the high and low status groups aboard, which mostly mean Norwegians and foreigners respectively. The most visible sign of status is where they eat and the quality of their cabin (Spjelkavik 1993, Serck-Hanssen 1997a). There are separate dining- and sitting rooms for Norwegians and foreigners. On ships where foreigners 4 I am mainly focusing on cargo ships carrying no passengers. The social environment on cruise ships or other passenger ships differ from cargo ships in important ways; there are more people aboard, the crew consists of several occupational categories who most likely differs in socio-economic and educational backgrounds and the working environment is less closed and isolated. 6 Does togetherness make friends? are working as officers, they still eat and relax together with the subordinates from their countries. Despite the fact that these men are living and working in the same social system for several months, the interethnic interaction is minimal. They eat separately and they hardly ever do the same social activities in their spare time. The contact they have during their workday is mostly based on orders and commands. A ship could in many ways be seen as what Goffman (1962) call a total institution, or a 24-hours-society (e.g. Aubert & Arner 1962; Sørhaug & Aamot 1982; Smith-Solbakken 1997). A total institution is a place of residence and work where a number of like-situated individuals, cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time, together lead enclosed, formally administered round of life. The ship is physically closed and isolated, and the sailors aboard are far from their home and families for a long period of time. Further, there is hard to separate work-relations from private relations, and the workday from the time off. Research about the ship as a multiethnic workplace, describes a segregated social environment, with hardly any social contact and interaction among sailors from different national, cultural and ethnic groups (for further readings see, Blystad 1992; Bedriftsrådgivning 1995; Dahle, Aall & Thorseng 1991; Serck-Hanssen 1996, 1997a, 1997b; Spjelkavik & Næss 1993; Johnsen & Kvande 1991). Researchers also focus on conflicts, problems of communication and intergroup hostility. The sailors themselves explain most of intergroup conflicts and hostility, by using stereotypes and categorisations of the out-group. Serck-Hanssen (1997a) has done observations on two different cargo ships crewed by Norwegians and Filipinos. He particularly explored the discourse among Norwegians and the discourse among Filipinos, and found that there was a striking difference between them. The discourse among Filipinos was mostly about their homesickness and less about the Norwegians (Serck-Hanssen 1997a, 1997b), most possible because they didn’t seem to contrast themselves to the Norwegians5. Being a sailor among Filipinos is mostly seen as a variety of labour migration in general, which is a common phenomenon on the Philippines. To be a labour migrant can be seen as a sacrifice for a better future. To show their homesickness and longing for their families could be a part of the suffering involved (SerckHanssen 1997b). The discourse among Norwegians, on the other hand, was mostly about being a good sailor, meaning physically strong, masculine, conscientious and responsible men, concerned about the ship and with a strong commitment to their work. They stereotyped 5 It could of course be argued that Serck-Hanssen as a Norwegian most likely had limited access to the discourse among the Filipinos, both due to language differences and his obvious relation to the Norwegian officers aboard. This methodological problem must therefore be taken into consideration when analysing distinctions between Norwegians and Filipinos. 7 Does togetherness make friends? themselves as being “good sailors” knowing about “practical seamanship”. The dedication to the life as a sailor and masculinity were core values, which expressed their attitude to the work. The historically and culturally background for this discourse and self-categorisation is partly that sailors in Norway since long back have been struggling for social acceptance in their work. Moral stigmas regarding alcohol and prostitutes, and their long vacations at times of the year when everybody else work are among reasons for this. The Norwegian sailors have also for many years been losing jobs to Filipinos and others on much lower salaries. Their emphasis on themselves as being good sailors must be seen as a result of their struggle for their jobs, and as a defence for their relatively higher salaries. Serck-Hanssen (1996, 1997a, 1997b) argues that the Norwegians were expressing their self-categorisations as being good sailors, mainly through contrasting themselves against the Filipinos. The Norwegians’ view of the Filipinos was contradictory to the criteria of being “a good sailor”, stereotyped as being physically weak, feminine, negligent and irresponsible. The fact that Norwegians are bigger than Filipinos is for example regarded as a sign of better working abilities and a key to be a better seaman. This has also to do with masculinity, as Filipinos are regarded as feminine and quite often labelled as homosexual. Serck-Hanssen explains this as an inquisitive result of the fact that Filipinos mix the English ‘he’ and ‘she’ because these pronouns are the same in Filipino language, and more importantly because Filipino sailors often are seen hand in hand which in fact is quite normal among Asian men. The Norwegian stereotypes of Filipinos in contrast to their self-stereotyping are clearly constructed as binary oppositions, i.e. “physically strong” versus “physically weak”, “masculine” versus “feminine”, “conscientious” versus “negligent”, and “responsible” versus “irresponsible”. As argued previous, the contents of stereotypes are commonly constructed as binary oppositions especially when one group is contrasting to another group and making distinct boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’. The stereotypes appear also to be constructed partly on the basis of different ideas about masculinity. The social environment on ships is highly male-dominant, and there has always been a very masculine working environment among sailors. The work identity as seafarers or sailors most likely differs with nationality or as a result of cultural differences, and it is obvious that culture has a significant influence on how and why stereotypes are made as several researchers have examined (see e.g., Hinton 2000; Lippman 1922). Does togetherness make friends? 8 Stereotypes and intergroup contact The main topic being discussed in this paper is the role of intergroup contact in change of negative stereotyping and prejudice. Intergroup contact does not necessarily reduce intergroup tension or prejudice, and there is enough evidence to show that people prefer interaction with others who are similar to themselves (e.g. Homans 1950). Work situations, on the other hand, seem to provide the best opportunities for intergroup contact and decategorization (Amir 1976). Billy Ehn found, through his observations in a multicultural factory in Sweden, that the work situation reduced intergroup tension and boundaries among workers across national, cultural and ethnic differences (Ehn 1981:155). It could be argued though, that intergroup contact might be needed primarily when intergroup conflict or tension is present. As previously described this seems to be the situation among sailors from different national, cultural and ethnic groups. In the sections below I will therefore discuss the process of decategorization, and also under what conditions intergroup contact could lead to reduction of prejudice and stereotypes. The process of decategorization The overall question asked is how to reduce intergroup tension and categorisation, and whether intergroup interaction and contact affect people in positive ways. I have already indicated, due to the social identity theory, that the major symptoms or consequences of category-based social interaction are de-individualisation and de-personalization of outgroup-category members. If the goal is to reduce intergroup prejudice and negative categorisation, intergroup interaction must thus involve the process of differentiation and personalization (Brewer & Miller 1984, Jensen & Pedersen 1991). The two processes can be distinguished conceptually and do not necessarily co-occur, though the two processes are necessary for reduction of prejudice and stereotypical attitudes. Differentiation refers to the distinctiveness of individual category members within that category, but does not necessarily imply the elimination of category boundaries that differentiate the in-group from the outgroup. Personalization involves responding to other individuals in terms of their private and personal relationship, which involves making direct interpersonal comparisons across category boundaries. Differentiation occurs when one learns information that is unique to the individual outgroup members, allowing one to draw distinctions among them and organise them into smaller subgroups. Such differentiation does not necessarily eliminate the tendency to view the subgroups as components of the larger social category. Differentiation may occur without personalization. One may acquire information that differentiates out-group members Does togetherness make friends? 9 under circumstances that entail no involvement of the self. Interaction that is highly task oriented may encourage differentiation among category members in terms of their task contribution, but such differentiation may have no personal implications. Brewer and Miller (1984) consider differentiation as a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for personalization. The elimination of categorised responding in an intergroup social situation requires both elements. Differentiated and personalised interaction is necessary before intergroup contact can lead to intergroup acceptance and reduction of social competition. The differentiation and personalization indicates two steps in the decategorization process. First step eliminates the negative stereotypes held against the individual; the second step eliminates the categorisation of the whole group where this person is a member. The processes of decategorization will only occur when the contact-situation takes place under favourable conditions as will be described below. Contact hypothesis The above discussion describes how decategorization might occur as a result of intergroup interaction and contact-situations. The conditions for this process to take place are of course opportunities for intergroup contact. Cook has formulated the phrase “acquaintance potential”, which refers to “the opportunity provided by the situation for the participants to get to know and understand one another” (Cook 1962:75). Some contact situations provide little opportunity for attitude change, and even if contact is established there is a good chance of a consequent increase in the negative attitude. One factor that may prove to be very important in ethnic contact situations, but has been almost completely ignored by researchers, is the attitude of the interacting or the potential interacting individuals toward ethnic contact. This, among other conditions, will be further discussed below. The contact hypothesis, as explored by several researchers (see e.g., Hinton 2000; Brewer & Miller 1984, 1996; Amir 1976; Jensen & Pedersen 1991; Cook 1962, 1984), is based on the following assumption: If stereotypes are inaccurate and people from one social group do not have much contact with the social group they view in a stereotypical way, then the stereotype is unlikely to change. If we can bring the two groups together in a positive way, then according to the contact hypothesis, the first group will view the second more accurately and stereotype change will occur. In other words, if ignorance and unfamiliarity promote hostility, then opportunities for personal contact between members of opposing groups should reduce hostility by increasing mutual knowledge and acquaintance. Several researchers have tested this hypothesis empirically, and thereby specified the conditions under which Does togetherness make friends? 10 intergroup contact might promote positive relations. As discussed below, intergroup contact does not seem to be quite enough for reaching the goal of reduced intergroup hostility. Characteristics of the contact situation and the interacting groups Of course, to believe that physical proximity alone would be sufficient to eliminate intergroup conflicts and stereotypes is naïve. The contact hypothesis has been carefully qualified to specify the conditions under which intergroup contact should promote positive relations. Due to that, theorists have discussed some conditions that are expected to influence the effectiveness of personal contact as a method of reducing intergroup hostility. Based on different theorists’ reconsiderations of the contact hypothesis (Amir 1976; Brewer & Miller 1984, 1996; Jensen & Pedersen 1991; Cook 1962, 1984), I will discuss intergroup interaction and contact-situations on ships. The main goal is to analyse why decategorization and elimination of prejudice does not necessarily occur among sailors in mixed crews, despite the fact that these groups are in contact for a longer period of time in the same social setting. As previously described the processes of decategorization will only occur when the contactsituation takes place under favourable conditions. The main question is then; under what conditions does contact lead to changes in stereotypical attitudes and reduction of intergroup tension? Cooperative interdependence Contact situations may differ in the degree to which they involve cooperative and competitive factors such as common or conflicting goals, shared concerns and activities, mutual interdependence or competition in the achievement of objectives and needs. Many theorists regard cooperative and competitive factors as extremely important considerations in intergroup contact, and some argue that the most effective way of inducing lasting attitude changes among participants is when the contact situation involves joint interaction, mutual interests, common goals, and active give-and-take contact situations. Cooperative task interaction has been found to reduce hostility between members of the cooperating social categories, and to increase intergroup friendships in comparison to competitive intergroup conditions. Brewer and Miller (1996) argue that effective cooperation should involve at least two important conditions of interdependence: shared goals (if one gains, we all gain) and shared effort (we must work together in order to achieve our goals). Like equal status, cooperative goals provide an opportunity for reducing the salience of category membership as Does togetherness make friends? 11 a relevant or important aspect of individual identity but whether it does so will depend on the task structure and the nature of the interaction it promotes among team members. Sailors’ mutual interest in keeping the ship going is an obvious dimension of their cooperative interdependence. One might assume that contact situations among sailors on the same ship involves a high degree of factors such as common goals, shared concerns and activities, and mutual interdependence in the achievement of objectives and needs. In one sense the cooperation involves both shared goals and shared effort, and therefore one could expect unity among sailors on the same ship. However, this appears not to be the entire picture. When it comes to opportunities and goals for the individuals there are considerable intergroup differences. First, the Filipino sailors are working on ten months contracts, while Norwegians are regular employees on the same ship. Filipinos do not know for sure if they ever will be working on the same ship for another period, and they are never in contact with the shipowner because they are recruited directly by an agent on the Philippines (SerckHanssen 1997a). Norwegians and Filipinos may therefor not have a shared interest in the ship. Second, there are not equal opportunities for the Norwegians and the foreigners when it comes to obtaining high status positions on most ships. Norwegians exclusively occupy the high status positions on the officer-level on many ships. This most likely produces various individual goals among sailors from different national groups, and it will probably influence on the willingness to adopt a cooperative intergroup attitude. Norwegians complains about the Filipinos being irresponsible and negligent, and claims that the ship would “fall apart” if Filipinos were in charge (see e.g., Spjelkavik & Næss 1993; Johnsen & Kvande 1991). One reasonable explanation to this could be that the Norwegians feel that they must justify their high status positions and their much higher salary compared to the Filipinos. Equal status The relative status of groups seems to be highly relevant for contact situations to reduce intergroup hostility and prejudice, and one could argue that in cases where no hindering conditions are present equal status contact is likely to produce positive attitude change (Brewer & Miller 1996, Jensen & Pedersen 1991). In many racially and ethnically mixed settings this is not so easily achieved, since participants come into the situation with preexisting status differences based on group membership. Even if there are no formal status differentials within the cooperative setting, ethnic identity may serve as a generalised cue for expectations of differences in ability and competence. Members of higher status groups may be unwilling to learn from or be influenced by members of lower status groups, and their Does togetherness make friends? 12 expectations of differences, and their expectations of lesser competence may be reinforced (Brewer & Miller 1996). Under these conditions, the relative positions of members of the cooperative work group are not truly “equal”. Cooperation may be undermined when the contributions of the two groups are not well balanced. Among others, Amir (1976) argues that the relative status of group members within the contact situation may be a more important factor for attitude change. If this is the case, then more success in improving intergroup relations may be achievable, since it is easier to assign members of minority and majority groups to equal status positions within a given situation than to bring together individuals who are of equal socioeconomic and educational status outside of the contact situation. It could be argued though, that pre-existing status differentials between groups tend to carry over into new situations, making equal-status interaction difficult or impossible. One the one hand, elimination of status differences within the contact setting may make category distinctions less salient. However, systematic attempts to reduce or reverse existing status differences may threaten members of the initially highstatus group, leading to resistance and attempts to reestablish in-group distinctiveness and positive status differentials. As previously described, the organisational structure on ships is highly hierarchic and authoritarian. The status differences between the in-group and the out-group are therefore far from equal in most work situations. The task-oriented communication between high- and lowstatus groups is mostly based on orders and commands, and the order-takers have little or no influence on their own tasks or working day. Since the high and low status groups hardly ever interact during meals or in their time off, the relative status of groups is rarely equal in contact situations. Of course there are situations not limited to work situations only, when individuals from different status groups and different national groups are interacting. When contact situations become more socially oriented, the possibilities for existing status differentials between the interacting groups to carry on into these situations are considerable. Even if there are no formal status differentials within the cooperative setting (e.g. contact situations between officers on the same status-level but from different national groups), ethnic identity may serve as a generalised cue for expectations of differences in ability and competence. There is for instance reported a number of conflicts when young Norwegian officers are being trained by more experienced Filipino officers. The reason given by Norwegians to these difficulties is that Filipinos have too much respect for Norwegians to train them or give them orders (Serck-Hanssen 1997a). Nations’ superiority in the world-economy is even given as an explanation of the status inequalities and distribution of tasks aboard. Does togetherness make friends? 13 Intimacy One important condition is the promotion of interactions that reveal enough details about members of the out-group to encourage seeing them as individuals rather than as stereotyped group members. In Brewers and Millers (1996) view this effect will depend on whether the focus of the interaction in the contact setting is primarily task oriented or interpersonally oriented. In task-oriented environment, the primary standard of evaluating fellow participants will be task requirements and contribution to task performance. This tends to narrow the range of information that is attended to and reduce perception of individual differences, thus limiting the opportunity to learn anything about group members other than their salient category identity. Work situations have for instance shown only limited attitude changes (Amir 1976). One possible explanation may be that work situations involve superficial interethnic contact. Even when the relationship becomes more personal, it is generally confined to the work situation only. In more socially oriented environments, on the other hand, evaluations of others will be made primarily with reference to the self, and thereby the process of personalisation is more likely to occur. When the intimate relations are established, the in-group member no longer perceives the member of the out-group in terms of stereotypes but begins to consider him as an individual and thereby discovers many areas of similarity. According to research on multiethnic-crewed ships, private or intimate contactsituations rarely occur. The contact among sailors across national boundaries and status groups are mostly task-oriented and rarely interpersonally oriented. But of course, there are individual exceptions. Ships are further known among mariners to have their own spiritual or social atmosphere. The descriptions “happy ship” and “unhappy ship” are commonly heard. When a ship is known as a “happy ship”, sailors can’t always tell the reason, but the good atmosphere seems to be there because individuals among the leadership are making an effort in having healthy relations aboard. In Weibust’s (1969) ethnographical study “Deep Sea Sailors” an informant describes the term “happy ship”: “… a happy ship, by which we meant a ship that was seaworthy, well-rigged and ship-shape with a skipper we could respect, mates who were sensible enough to treat their hands in a way that encouraged them to work – yes, and a cook who took pride in cooking good food…” Weibust 1969:451 Anyway, social relations on “happy ships” are less tensed and the possibilities for sailors having personal or intimate relations across national, ethnic and cultural boundaries are increased. Personal relations among sailors of different national groups and status groups Does togetherness make friends? 14 most likely would start the process of personalisation where individuals perceive each other as individuals (not primarily as a member of a category) and thereby discovers many areas of similarity. However, this does not necessarily leads to changes in the group stereotype. The information about the individual could most likely be irrelevant to existing stereotypes, and the new information may fail to be noticed or represented in memory. Friendships across group boundaries will then be the exception more than the rule, and do not necessarily lead to elimination of stereotypes. Amount and frequency of contact There is a strong link between the intimacy of the contact situation and the amount and frequency of contact. Proximity and frequency of contact as well as other factors may exert important influence in determining both the amount and nature of intergroup contact. Causal intergroup contact typically has little or no effect on basic attitude change (Amir 1976). When such contact is frequent, it may even reinforce negative attitudes especially when it occurs between nonequal status groups. Frequency of contact can in some case produce intimate relationships and advance better intergroup relations, but in other circumstances it may strengthen prejudice and ethnic hostility. The structural features of a ship make sailors stay together for long periods at the time. Intergroup contact is therefore more or less by force, both frequent and continuous. As argued, the ship could be seen as a total institution or more precisely, an isolated and closed institution where people are staying for quite long periods. Their sailing-periods vary though. Filipinos mostly have periods of ten months on one ship before going home for one or two months, while Norwegians most commonly have periods of six weeks up to four months before going home. One might assume that sailors should have more than enough time for creating friendships and eliminate stereotypical attitudes towards each other. However, when the contact is task-oriented and causal it often has a minor effect on basic attitude change, and as argued above, when such contact is frequent it may even strengthen negative attitudes especially when it occurs between unequal status groups as in this case. Institutional support and egalitarian norms The effectiveness of interethnic contact on reduction of stereotypes is greatly increased if the contact is sanctioned by institutional support. The support may come from the law, a custom, a spokesman for the community, or simply from social atmosphere and general public agreement as discussed in the next paragraph. The social structure in the work place should Does togetherness make friends? 15 encourage equality norms and intergroup contact. In many intergroup situations neither the social atmosphere nor institutions favour intergroup mixing for a variety of reasons, and it may strongly hinder the development of successful intergroup contact and ethnic integration (Amir 1976). Institutional support for ethnic interaction and reducing of prejudice is important partly because it produces social desirability and consequently people will be more willing to act in the required direction. Together with institutional support the shared values that participants bring to or acquire in the contact situation will be of critical importance. When norms favouring intergroup equality and expression of individuality are salient, adherence to such values provides an alternate source of positive self-identity that may replace social category identity. One might say that the institutional support on a ship favours unequal intergroup relations. The hierarchic social structure is quite visible on the ship, and the most visible sign of status is where one eats and the quality of the cabins. There are physical distinctions between high and low status groups, like separate dining- and sitting rooms, and during meals each sailor has his regular seat which fit with his status position aboard (Spjelkavik 1993; Serck-Hanssen 1997a). This physical structure on ships goes long back in history. Traditionally, there has always been a highly hierarchic structure on ships and still many old sailors support this inequality aboard. During the 1960s and 70s researchers did experiments on ships, with an attempt to make a ship’s organisational structure consistent with democratic and egalitarian values (e.g. Roggema & Hammarstrøm 1975). However, it seems like these experiments failed in creating ships based on lasting democratic and egalitarian norms and values (Blystad 1992). The unequal opportunities among sailors when it comes to conditions of work, as described earlier, should also be mentioned as part of the institutional structure that may hinder the development of successful intergroup contact. Intergroup anxiety One factor that may prove to be very important in ethnic contact situations is the attitude of the interacting or the potential interacting individuals toward ethnic contact. Negative affect or emotions, such as anxiety, plays an important role in maintaining intergroup prejudice. Researchers have provided evidence for a direct link between experienced anxiety and the outcomes of intergroup contact. Anticipated contact with out-group members in a competitive environment seems to produce intergroup anxiety. Intergroup anxiety is quite often viewed as both a determinant and a consequence of intergroup contact (e.g. in Greenland & Brown 1999). Brewer and Miller (1996) argue that the nature and the quality of contact experiences, Does togetherness make friends? 16 rather than the frequency of contact, makes the biggest difference in intergroup attitudes. According to social identity theory as previously described, individual’s identity is partly based on membership in significant social categories or groups. The value of group membership depends upon comparison with other relevant groups, which results in preference of in-groups over out-groups and the making of distinct boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’. This leads to stereotypes of out-group members, and can easily lead to discrimination and intergroup anxiety. Intergroup anxiety might prove to be of importance in this case, though it is hard to assume anything because the available data of multiethnic-crewed ships tells nothing clear about this. The fact that Norwegian sailors feel pushed out by foreigners who are working on much lower salaries might lead to intergroup anxiety, or at least some sense of hard feelings among Norwegians. However, sailors are after all used to the highly global setting they are working in, and one must assume that most of them also have chosen this occupation partly because of it being highly international. Disconfirmed stereotypes The interaction should encourage behaviour that disconfirms stereotypes that the group hold of each other (Brewer & Miller 1996). Maximizing the opportunity to learn stereotypeinconsistent information about out-group members is closely related to the differentiation component of the decategorization process as described above. The crucial point is that the contact situation must include a diverse representation of out-group-category members. Brewer and Miller argue (1996) that it takes exposure to many diverse group members to break down stereotypes and the perceived homogeneity of out-groups. A problem though, seems to be that information about an individual that is irrelevant to existing stereotypes may fail to be noticed or represented in memory. Information that is highly inconsistent with stereotypic expectations is more likely to be salient and well remembered, but does not necessarily lead to changes in the group stereotype (Brewer & Miller 1984). Instead, the inconsistent individual may be subcategorised as a special case or a subtype within the social category without any overall effect on categorisation. Reduction of stereotyped expectations requires frequent exposure to multiple types of disconfirming information that is dispersed across a large number of out-group members. Such information reduces the usefulness of category identification as a basis for clarifying individuals. As the category becomes more and more finely differentiated, the boundaries between categories become less salient, which increases the probability of a more personalised interpersonal evaluation. The conditions of Does togetherness make friends? 17 interaction must encourage attending to individual differences on a number of dimensions, and as mentioned previously; highly task-focused interactions do not ordinarily lead to such attention. In general, a variety of contact experiences produce more generalised change than experiences that are limited to a few group members or a single interaction setting. Sailors are living together on the same ship for several months, so it is obvious that they get to know different sides of their co-workers. However, it seems like the contact between different national groups is highly task-oriented and not very intimate despite the fact that they are living on the same boat for å long period of time. In fact, many sailors describe life at sea as very lonely because they quite often spend their time off alone in their cabin (Serck-Hanssen 1997a). Highly task-oriented interactions do not encourage attending to individual differences, and thereby break down stereotypes and the perceived homogeneity of the out-group. A more important point though, might be that the similarities among sailors from the same national group most likely are considerable, in terms of socio-economical and educational background. Intergroup contact situations then, do not include a diverse representation of out-group-category-members that is necessarily to learn stereotypeinconsistent information about out-group members. Summary I have throughout this paper discussed the relationship between stereotypes and intergroup contact on multiethnic-crewed ships. Stereotyping is the process of ascribing characteristics to people on basis of their group membership, and if stereotypes of one group are shared by members of another group they would be labelled as social stereotypes. Several social scientists have examined the relationship between stereotypes and intergroup contact, but there is no clear evidence stating the role of contact in reduction of intergroup hostility and elimination of stereotypes. In this case one might assume that sailors, who are working and living together in a small and clearly demarcated social system over a long period of time, would generate friendships and eliminate intergroup tension and hostility. However, empirical studies show that this is far from the reality. By discussing the contact hypothesis and its prerequisites I have explained why decategorization does not occur in this case. There seem to be various conditions on ships that do not promote positive relations. The highly hierarchic and authoritarian organisational structure on ships seems to be of considerable importance, because of the status differences between the interacting groups. There are further considerable intergroup differences when it comes to individual opportunities, goals and Does togetherness make friends? 18 effort. Despite the frequency and amount of intergroup contact, positive relations do not seem to be established. One reason for this might be that the contact is highly task-oriented and not very intimate and therefore do not promote disconfirmed stereotypes in general. References Amir, Y. (1976) “The Role of Intergroup Contact in Change of Prejudice and Ethnic Relations”, in: Katz, P. A. (ed.) Towards the Elimination of racism, New York; Pergamon Press. Aubert, V. & Arner, O. (1962) The ship as a social system, Oslo: Arbeidspsykologisk Institutt. Bedriftsrådgivning A/S (1995) Flerkulturell skipsdrift. Oslo: Bedriftsrådgivning AS. Blystad, R. (1992) Verne og miljøproblematikk på skip med flerkulturell bemanning. WRI notat 4/85. Oslo: Work Research Institute (WRI). Brewer, M. B. & Miller, N. (1984) “Beyond the Contact Hypothesis: Theoretical Perspectives on Desegregation”, in: Miller, N. & Brewer, M. B. (ed.) Groups in Contact. The Psychology of Desegregation, New York: Academic Press. Brewer, M. B. & Miller, N. (1996) Intergroup relations, Buckingham: Open University Press. Cook, S. W. (1962) “The systematic analysis of socially signicant events: A strategy for social research” in: Journal of Social Issues, 62:18. Cook, S. W. (1984) “Cooperative Interaction in Multiethnic Contexts”, in: Miller, N. & Brewer, M. B. (ed.) Groups in Contact. The Psychology of Desegregation. New York: Academic Press. Dahle, Aall & Thorseng (1991) Skip med flernasjonal bemanning. Trivsel og sikkerhetsmessige forhold. Høvik: Det Norske Veritas. Ehn, B. (1981) Arbetets flytande gränser. En fabrikstudie. Stockholm: Bokförlaget Prisma. Goffman, E. (1959) The presentation of self in everyday life, New York: Penguin Books. Goffman, E. (1962) Asylums: essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates, Chicago: Aldine. Greenland, K. & Brown, R. (1999) “Categorization and intergroup anxiety in contact between British and Japanese nationals”, in: European Journal of Social Psychology, 29. London: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Hinton, P. R. (2000) Stereotypes, Cognition and Culture, East Sussex: Psychological Press. Homans, G. (1950) The Human Group, New York: Harcourt Brace. Jenssen, A. T. & Pedersen, E. (1991) ”Jo mer vi er sammen dess gladere blir vi”? Kontakt, vennskap og konflikt mellom nordmenn og innvandrere. in: Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning, Årgang 32. Johnsen, I. og Kvande, M. (1991) Menneskelige og organisatoriske faktorer ved drift av skip. Trondheim: Norges Teknisk-Naturvitenskapelige Forskningsråd (NTNF). Lippman, W. (1922) Public Opinion, New York: Harcourt Brace.Oakes, P., Haslam, S. A., Turner, J. C. (1994) Stereotyping and social reality, Oxford: Basil Blacwell. Roggema, J. & Hammarstrøm, N. K. (1975) Nye organisasjonsformer til sjøs. Oslo: Tanum-Norli. Serck-Hanssen, C. (1996) ”De er ikke ordentlige sjøfolk, de er her bare for å tjene penger”. in: Hovedfagsstudentenes årbok, 9. Årgang, Universitetet i Oslo: Institutt og museum for Antropologi. Serck-Hanssen, C. (1997a) Det er et ensomt liv. En analyse av to skip med filippinsk og norsk mannskap. Universitetet i Oslo: Hovedoppgave i antropologi. Serck-Hanssen, C. (1997b) The Construction of Distance and Segregation onboard Ships with mixed crew. Unpublished manuscript for a speech presented at the 4 th International Symposium on Maritime Health, Oslo, June 1997. Smith-Solbakken, M. (1997) Oljearbeiderkulturen. Historier om cowboyer og rebeller, Trondheim, NTNU: Skriftserie fra historisk institutt nr. 17. Spjelkavik, Ø. og Næss, R. (1993) Flernasjonale utfordringer på norske skip. Oslo: AFI, Rapport 7/93. Sumner, W. G. (1906) Folkways, New York: The New American Library. Sørhaug, H. L. & Aamot, S. (1981) Skip og samfunn, Oslo: Arbeidspsykologisk institutt. Tajfel, H. (1978) (ed.) Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. London: Academic Press. Tajfel, H. (1981) ”Social Stereotypes and Social groups”, in: Turner, J. C. & Giles, H. (eds.): Intergroup behaviour, Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. (1986) “The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour”. In: Worchel, S. & Austin, W. (eds.) Psychology of intergroup relations, Chicago: Nelson-Hall. The Norwegian Shipowners Association (1999) Quarterly report about shipping and offshore, no: 4/99. Does togetherness make friends? 19 Weibust, K. (1969) Deep Sea Sailors. A study in Maritime Ethnology. Stockholm: Nordiska Museets Handlingar 71.