F I R S T D R A F T

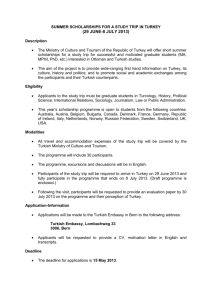

advertisement