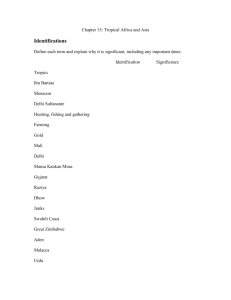

Fundamentalism and Outreach Strategies in East Africa – Christian

FUNDAMENTALISM AND OUTREACH

STRATEGIES IN EAST AFRICA:

CHRISTIAN EVANGELISM

AND MUSLIM DA‘WA

ISITA Colloquium May 2003

Paper by: John A. Chesworth,

St. Paul’s United Theological College,

Limuru,

Kenya chesworth@wananchi.com

1

ABSTRACT

:

fundamentalism and outreach strategies in east africa: christian evangelism and muslim da‘wa

The paper gives an overview of the methods of outreach being used by Christians and Muslims in

East Africa and the reaction to them. It attempts to address the role that fundamentalism, from outside East Africa, has had on outreach, with particular reference to Islam.

Two Muslim groups are examined to illustrate some of the methods used:

[1] Groups such as Jumuiya ya Wahubiri wa Kiislamu Tanzania (JUWAKITA) (Society of

Muslim Preachers of Tanzania) actively propagate their message through public debates.

A detailed study is made of the use of mihadhara (public debates) by Muslims, and the

Comparative Religious Studies approach, looking at the work of two Tanzanian Muslim

Preachers, Muhammad Ali Kawemba and Musa Fundi Ngariba. The influence of the

South African Ahmed Deedat on the approaches used is also examined.

[2] Warsha ya Waandishi wa Kiislam (Muslim Writers’ Workshop) the origins and development of this influential group based in Dar es Salaam are examined. The paper seeks to demonstrate how their mentor, Muhammad Hussein Malik, a Pakistani, can be seen as being one of the earliest teachers responsible for introducing the writings and teachings of Sayyid Qutb and Sayyid Abul A‘la Maudūdī to Muslim youth in East Africa.

The paper examines aspects of the outworking of fundamentalism in East Africa. In looking at mihadhara and the work of Warsha it attempts to demonstrate a significant factor in fundamentalism, that is the desire for a return to the “fundamentals” of the faith, in this case

Islam.

John A. Chesworth

BEd (Durham), BA (Th) (CNAA), MA (IS) (Birmingham), PhD candidate (Birmingham),

Head of Department of Religions and Missiology, St. Paul’s United Theological College,

Limuru, Kenya

2

FUNDAMENTALISM AND OUTREACH STRATEGIES IN EAST AFRICA:

CHRISTIAN EVANGELISM AND MUSLIM DA‘WA

INTRODUCTION

The paper looks at the role of fundamentalism in Outreach, both for Christian Evangelism and Muslim da‘wa . Fundamentalism is a misunderstood term, which can be emotive. It is an idea with Christian origins, applied to groups who wished for a return to the ‘fundamentals’ of the faith. In recent times it has been mis applied to Muslims, when it would be better to call such groups, either Reformist or Revivalist. However in both Christianity and Islam there are groups who could be best termed as Fanatics, these are the groups that may be seen as ‘fundamentalists’ in the context of this paper.

Within the African context fundamentalism is becoming increasingly significant as both

Muslim and Christian groups seek to influence the political structure of the continent. Jeff

Haynes in Religion and Politics in Africa discusses this in his chapter “Religious

“Fundamentalism” and Politics”.

1 He examines the claims that (1) “religious fundamentalism in

Sub-Saharan Africa may be little more than a manifestation of the impact of foreign religiousideological manipulation” and (2) “that fundamentalism is no more than a highly negative reaction to modernization on the part of disoriented, manipulated individuals”.

2

Both external influence and the internalising or indigenizing of fundamentalist ideas are seen in East Africa and the methods of outreach used by Muslims and Christians.

1 Haynes, J. Religion and Politics in Africa , (1996 Nairobi: EAEP), pp 197-231.

2

Haynes, J. Religion and Politics in Africa , (1996), pp 197-198.

3

Haynes sees that Christian fundamentalism has been readily adopted and has become a part of popular religion and been indigenized. This has led to the phenomena of:

African fundamentalist Christians (sometimes referred to as ‘born again’, ‘reborn’ or

‘charismatic’) normally believe in experiential faith, the centrality of the Holy Spirit, the spiritual gifts of glossolalia and faith healing, and the efficacy of miracles. The fundamentalist world-view is informed by belief in the authority of the Bible in all matters of faith and practice.

3

Such Christians and churches have tended to develop a “conservative” pro-government stance. In

Kenya at the end of the “Moi years”, 4 the era of the second President of the Republic of Kenya, who had become increasingly autocratic and ruled from 1978 to 2002, it was such churches that were strongly in favour of the government and spoke out against the main-line Protestant and the

Roman Catholic church leaders, who condemned the government’s actions and corruption.

Whereas Haynes is of the opinion that Islamic fundamentalism has not found a niche in

Africa, because “when religious dogmatists do seek to impose what many of their co-religionists perceive as anathema, their goals are not realised”.

5 Whilst it is true that in East Africa the traditional Shāfi‘ī

‘ulamā’

6 have reacted negatively to such dogma, such outright rejection has not been observed, and the younger Muslims have been attracted by such dogmatic teaching as will be shown in the paper.

The outcome is that when fundamentalists undertake outreach, it has a distinct effect on the ways in which they address peoples of other faith groups. To illustrate this, the paper looks initially at Outreach Strategies through Public Meetings, examining how Christian groups have used open-air meetings from the earliest times of Christian Missionaries arriving on the East

3 Haynes, J. Religion and Politics in Africa , (1996), pp 202.

4 President Daniel T. Arap Moi, second President of Kenya, August 1978 to December 2002.

5 Haynes uses Nigeria as his model for viewing Muslim fundamentalism. Haynes, J. Religion and Politics in Africa ,

(1996), pp 198. The recent study Muslim Modernity in Postcolonial Nigeria by Ousmane Kane on the Yan Izala in

Kano gives an interesting insight on the rise of externally influenced dogmatists Kane, O. Muslim Modernity in

Postcolonial Nigeria , (2003 Leiden: Brill).

4

African coast, during the middle of the 19 th Century. The study then specifically looks at the use of mihadhara (public debates) by Muslim groups, such as Jumuiya ya Wahubiri wa Kiislamu

Tanzania (Society of Muslim Preachers of Tanzania, JUWAKITA). The paper concludes by examining one Muslim group in detail Warsha Ya Waandishi Wa Kiislam (Muslim Writers

Workshop), popularly known as Warsha , and the influence of an expatriate on its formation and ethos.

7

OUTREACH STRATEGIES

CHRISTIAN EVANGELISM: EARLY OPEN AIR OUTREACH IN EAST AFRICA

Christian Evangelism using Public Rallies was a part of the strategy of some of the early missionaries in East Africa. The reports of the approaches that they used then are reflected in some of the methods described below.

The Church Missionary Society (CMS), which arrived in East Africa in 1844, was the first of the modern missionary societies to work in the area. The missionaries primarily were working amongst the “pagans”, but being based on the coast around Mombasa, they were in close contact with the Muslim community. The Annual Reports of the Society: Proceedings of the

Church Missionary Society for Africa and the East give “stirring” examples of the work and the approaches used. In 1894, Revd. W.E. Taylor describes the open-air meetings that were held four times a week in the market-place:

The market-place, the private property of H.E. the Arab Governor, is a piece of land adjoining the bazaars, occupied in almost its whole extent by several large and high palm-

6 Shāfi‘ī , the Sunni School of Law followed in East Africa. Ibn Battuta reports that the Muslims were followers of the Shāfi‘ī when he visited in the 14 th Century (Hamdun, S. & King, N. Ibn Battuta in Black Africa , (With a new foreword by Ross E. Dunn), (1994 Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers), p 22. ‘ulamā’ – Scholars – plural of ‘ ālim .

7 Having worked in Tanzania from 1988-2000, many of the examples in the paper are taken from Tanzania.

5 leaf roofed sheds, and surrounded by the shady recesses of the “ gahawas ,” or coffeeshops, where buyers and dealers solace themselves in the intervals of business. Here amongst the fish, flesh, and fowls, and the piles of country produce and cries of Native auctioneers, in a motley crowd of Swahilis and Swahili-speaking people from the upcountry tribes, the coast, and shores of Asia, we have found a regular preaching site in a shed devoted to barbers and razor-grinders, and seek to preach by word and song the

Gospel, which we know is the power of God unto salvation to every one that believeth, to the Greeks foolishness, to the Jews a stumbling-block, and to the Mohammedans 8 both these; but to them that are called – Jews, Greeks, and Mohammedans – Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. … Wherever one goes one hears the words, “Tela sizue!”

9 (Taylor, don’t make innovations!) being the refrain of one of the most popular songs, a sort of parody of one of our choruses; or else it is “Stop and tell us something about Isa (Jesus)!”.

10

Other CMS missionaries worked with Taylor, and the pattern of meetings in the Mombasa

Market, and at nearby Zizi la K’onzi, carried on after his departure in 1897.

11 Taylor’s songs became well known and spread along the coast both to the north and south of Mombasa.

12 This approach was also used elsewhere: in his Annual Letter to the CMS for 1894 he describes a holiday in Lamu, where he introduced open-air meetings to the German missionaries of

Neukirchen Mission:

We had great pleasure in inaugurating market services similar to those at Mombasa, and these have been kept up ever since by the German Neukirchen missionaries. We found the fame of Mombasa had preceded us, and the town was ringing with our choruses and parodies on them – or, rather, answers directed against our Gospel. … The Germans, … expressed themselves as considerably cheered by our visit, and especially at the new way of “reaching the masses” which we … introduc[ed] to them. They said that in Germany

8 “Mohammedans” used for Muslims, showing the misunderstanding made by many Christians in 19 th Century that

Muslims were named as followers of Muhammad, rather than ones who have submitted to God.

9 P.J.L. Frankl comments on Taylor’s use of songs: “[That] he was the unwitting cause of a new genre of Swahili poetry … mahadhi ya Tela ‘Taylor’s tune’. … songs composed by the wat’u wa mji [people of the town] in response to the hymns composed or translated by Taylor.” Frankl, P.J.L. “W.E. Taylor (1856-1927): England’s greatest

Swahili scholar”, Afrikanistiche Arbeitspapiere No. 60 Swahili Forum VI , (1999), pp 161-174, p 166.

10 Church Missionary Society Archives (Held at University of Birmingham) Proceedings of the Church Missionary

Society for Africa and the East for 1893 , (1894), p 38.

11 In 1909 Rev. G.W. Wright in Mombasa reports that “our senior native clergyman, the Rev. I.M. Semler, has come over from Frere Town to help in the open-air work” Church Missionary Society Archives Extracts from the Annual

Letters of the Missionaries for the year 1909 , (1910), p 200.

12 Taylor reports in his annual letter for 1894: “The interest excited by the services has spread all along the Swahili coast, not only northward, but also to the south. Even at Mgau (the populous strip of Swahili coast lying furthest south, just north of Mozambique) a Swahili gentleman, … who has made a trip there during the year, tells me that all were asking about the new departure at Mombasa, and that the hymns we sing in the sokoni (market-place) had made their way, no doubt in a very fragmentary state, even there” Church Missionary Society Archives Extracts from the

Annual Letters of the Missionaries for the year1894 , (1895), p 8.

6 open-air meetings were so rare that they had no experience in this so public a method of scattering the good seed.

13

However, Taylor and the others did not always find it easy, and met with considerable opposition and wit:

We have made an invariable habit for some months past of adjourning from the marketplace, where the bustle and danger, the dust and heat, are excessive, to the more airy regions of Zizi t’a K’onzi, a cattle-pen, … Here, under the shady and breezy eaves of some native houses looking on to an open space we have our second meeting. It presents a great contrast to the market, but sometimes the opposition can be very noisy here, too.

Once I was suffering from an affection of the ears and had stuffed them with cotton-wool.

… The quick-eyed opponents saw this, and immediately objected. “He has stopped his ears; he is afraid to hear our arguments.” Of course I had to remove it.

14

The numbers attending the meetings are reported by F. Burt in his Annual Letter of 1896 as being around 100 at the Market-Place and 150-200 at Zizi la K’onzi.

15

As the missionaries moved inland the use of open-air meetings continued, R. Pittway writes positively of its use in Nairobi and Nakuru in the 1920s and 1930s but as not being so successful in the late 1940s:

Nairobi 1924: On Sunday afternoons we have open air meetings in villages which are composed largely of Mohammadens. … Quite a number of Mohammadens stand and listen.

16

Nakuru 1930: The open air meetings are well attended and many Mohammadens quietly listen to the Gospel on these occasions; and from remarks heard it is clear that they think about, and discuss the messages given.

17

Nairobi 1935: The Open Air Meetings have been well attended and a greater number of our African brethren have desired to share in this profitable task. There have been attendances of 200-400 at these open air meetings and many have been reached for the

Gospel who would not be reached through ordinary services and classes.

18

Weithaga 1948: Open air work continues but is becoming increasingly difficult; workers not only being “heckled” by the opposition, but sometimes physically attacked.

19

13 Church Missionary Society Archives Extracts from the Annual Letters of the Missionaries for the year1894 ,

(1895), p 8.

14 Church Missionary Society Archives Extracts from the Annual Letters of the Missionaries for the year1895 ,

(1896), p 586.

15 Church Missionary Society Archives Extracts from the Annual Letters of the Missionaries for the year1896 ,

(1897), p 11.

16 Church Missionary Society Archives, 1924 Pittway Annual Letter: Annual Letters File (G3 AL 1917-1934)

17 Church Missionary Society Archives, 1930 Pittway Annual Letter: Annual Letters File (G3 AL 1917-1934)

18 Church Missionary Society Archives, 1935 Pittway Annual Letter: Annual Letters File(G3 AL 1935-1949)

19 Church Missionary Society Archives, 1948 Pittway Annual Letter: Annual Letters File (G3 AL 1935-1949)

7

CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN OUTREACH

The foregoing examples serve to show that the current use of public meetings has a long history within East Africa. In the post-war period in the run-up to Independence, Christian outreach continued to be important. The East African Revival movement was very active in outreach. Also there were a series of public meetings with international, mainly American speakers, including Billy

Graham who in 1960 conducted “sensational rallies in Nairobi and Kisumu”.

20 Joseph Galgalo reports that other similar meetings were conducted by T.L. Osborn in Mombasa in 1957 and later on during the 1960s which gave “impetus for open air preaching, which has since become the most popular method of evangelism in Kenya”.

21 The visit by Oral Roberts, in 1968 when he held healing rallies in Nairobi, are also cited as a major influence in the use of public rallies and the introduction of Pentecostal churches.

22 From the mid-1980s Christians regularly began to organise outreach in the form of public rallies.

23 Ludwig reports on the growth of one organisation:

Since 1986, at least one ‘crusade’ a year has taken place in Dar es Salaam. In order to organise a ‘crusade’, representatives of Assemblies of God, Lutherans, Anglicans and other churches work together in the ‘Big November Crusade Ministries’. This organisation was officially registered in 1989/90. In 1990, it began to work outside Dar es Salaam and in

1991 there were ‘crusades’ in not less than twelve regions.

24

20 Shorter, A. & Njiru, J.N. New Religious Movements in Africa , (2001 Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa), p 18.

21 Galgalo, J.D. “Impact of Pentecostalism on the Mainline Churches in Kenya”, Encounter 3, (2003), pp 28-42, p

30.

22 Shorter, A. & Njiru, J.N. New Religious Movements in Africa , (2001), p 18.

23 These often show Christian insensitivity to Islam by being called “Crusades”, which triggers memories of the medieval Crusades, which are still vivid in Muslim minds. See Maalouf, A. The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, (1984

London: Al Saqi Books) and Hillenbrand, C. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives , (1999 Edinburgh: EUP). However the word “crusade” has so much come to identify this type of outreach that Muslims are using the word in their own outreach campaigns. A Jinja-based Islamic preaching group, “ Ma ‘ kaaz Islammiyya that uses the Bible to abuse

Christians and their beliefs. They preached in Western Uganda, including Kabale for the whole month of April 2002”

(Mugyenzi, p 12 Footnote 37), is reported to called their meetings “Crusades”, Solomon Mugyenzi, answer to a question of clarification after delivering a paper “Christian-Muslim Economic Relations In Uganda”, Accra, Ghana,

July 2002.

24 Ludwig, F. “After Ujamaa: Is religious revivalism a threat to Tanzania’s stability?”, In Questioning the Secular

State, D. Westerlund (Ed.), (1996 London: Hurst & Company: pp 216-236), p 223.

J.R. Mlahagwa 25 refers to the Big Harvest Crusades, that have been organised annually in Dar es

Salaam by Nyumba kwa Nyumba (House to House Ministries) since the late 1980s.

These “Crusades” usually take the form of rallies, held on open ground, in an easily accessible part of the city.

26 Meetings are held daily in the late afternoon for up to two weeks. They usually have several choirs and a well-known speaker, either from within the country or abroad.

Groups involved in similar outreach include: Christ for All Nations (CfAN). Its leader, Reinhard

Bonnke, a German who is a regular visitor to Tanzania and Kenya, regards “Africa as a field ripe for harvest.” Ludwig comments on this approach “[it] does not leave much room for dialogue with other religions. In Tanzania [Bonnke] has to refrain from direct attacks, but nevertheless he uses a

‘powerful’ militant language”.

27

Bonnke has spoken out against Islam and Crusades have been cancelled in Nigeria and

Mali because of fears of violence arising from his views. Paul Gifford discusses Bonnke’s attitude to Islam and Muslims in Africa:

Bonnke is quite open that he is conducting a campaign against Islam, moving against the

Muslim lands of North Africa. Of his Jos crusade, Revival Report says: “Muslims vie militantly for control of the city. That fact … made the Jos crusade crucial for CfAN in its evangelistic commitment to drive upward into Africa.” And elsewhere: “Jos was one of

CfAN’s most strategically important for advancing north into Nigeria’s Moslem strongholds”. This he considers his divine mandate: “We are even knocking on the gates of the Islamic fortresses, because Jesus has said ‘Knock and it shall be opened unto you’”.

Everyone understands exactly whom he is referring to when he writes: “We are gripped by a holy determination to carry out the Great Commission of our Lord, which is a command to attack the strongholds of Satan. The widely-heralded, seemingly unstoppable advance of Christianity, exemplified by Bonnke and his seemingly limitless resources, personnel and technology, appears as the ultimate threat to Muslims. To Muslims,

Bonnke’s aim is the elimination of every Mosque from Africa in the shortest possible

8

25 Mlahagwa, J.R. “Contending for the Faith: Spiritual Revival & the Fellowship Church in Tanzania”. In East

African Expressions of Christianity, T. Spear & I.N. Kimambo (Eds.), (1999 Oxford: James Currey: pp 296-306), p

301.

26 Mnazi Moja and Jangwani are popular locations in Dar es Salaam; Jamhuri Stadium in Dodoma; Uhuru Park and

Jevanjee Gardens in Nairobi.

27 Ludwig, F. “After Ujamaa: Is religious revivalism a threat to Tanzania’s stability?” (1996), p 223.

9 time. This elimination is to be achieved through evangelisation and not through arson but in Muslim eyes the ultimate effect is the same, their cultural annihilation.

28

In addition to Bonnke’s views on Islam, Gifford also examines the methods of conducting outreach by large Public rallies, including the sheer logistics and statistics involved.

29 He also analyses the content of sermons delivered in a series of thirteen meetings conducted in Zimbabwe.

30

Of particular interest is the account of the Nairobi Crusade conducted in Mathare Valley in February

1991. Gifford makes specific reference to how Bonnke deals with Islam:

[By] definition Muslims can only be part of Satan’s Empire. At Mathari [ sic ] Valley Bonnke welcomed all: “Whether Christian or not, Hindu, Muslim, it doesn’t matter. Jesus loves you,

Jesus loves you, Jesus loves you. He’s willing to save and heal you, whatever your background, and I’m very happy you are here”. The happiness arises from the possibility of their turning to Jesus. If they fail to grasp this opportunity, however, they remain in Satan’s power and will be damned eternally.

31

Colin Whittaker, in his biography of Reinhard Bonnke, reports on the Mathare Valley campaign, having previously described the rallies in Nairobi and Nakuru and that President Moi had requested an ‘audience’ with Bonnke. Further he describes how the president had eight taken cabinet ministers with to attend a rally and three had openly professed Christ.

32

At the close of the Nairobi event, some of the Kenya press challenged Reinhard Bonnke:

‘Why do you come to a beautiful park and preach the gospel? Why don’t you go to a slum area, like Mathare Valley?

It was Reinhard’s kind of challenge, and his response was immediate, ‘When I come back to

Nairobi, Mathare Valley is the place where I shall go.’ In February 1991, he was able to keep his word.

At first, people from outside the area were afraid to attend the campaign in this notorious location because of the many drug addicts, criminals, prostitutes and thieves known to live there. But as Reinhard lifted up ‘the Christ who was the friend of publicans and sinners’ they were captivated. He proved in the dens and brothels of Mathare Valley that Christ did not come to call the righteous but sinners to repentance, and the great Physician worked outstanding miracles of body and soul.

28 Gifford, P. “Reinhard Bonnke’s Mission to Africa, and His 1991 Nairobi Crusade”, In New Dimensions in African

Christianity , P. Gifford (Ed.), (1992 Nairobi: All Africa Conference of Churches), pp 157-182, p 171.

29 Gifford, P. “‘Africa Shall be Saved’. An Appraisal of Reinhard Bonnke’s Pan-African Crusade”, Journal of

Religion in Africa XVII:1, (1986), pp 63-92, see pp 63-65 and “Reinhard Bonnke’s Mission to Africa, and His 1991

Nairobi Crusade”, (1992), pp 157-160.

30 Gifford, P. “‘Africa Shall be Saved’. An Appraisal of Reinhard Bonnke’s Pan-African Crusade”, (1986), pp 65-

78.

31 Gifford, P. “Reinhard Bonnke’s Mission to Africa, and His 1991 Nairobi Crusade”, (1992), pp 163.

32 Whittaker, C. Reinhard Bonnke: A Passion for the Gospel, (1998, Eastbourne, Kingsway), pp 179-180.

10

The presence of God somehow permeated the area and crime dramatically decreased.

33

Whittaker’s entire report of the Mathare Valley campaign is given and no mention of the content of his preaching is given nor the references to Islam that Gifford has. Bonnke and his approach to evangelism is questioned by Christians as well as complained of by Muslims.

Whittaker’s book on Bonnke refers to him as the ‘Combine Harvester’, reflecting on his mass approach of evangelism.

34 Discussing Bonnke’s rallies and other International evangelists with

Kenyans, support from local churches in preparation for campaigns is done and follow-up is arranged.

However with weekly rallies in Uhuru Park and regular reports of thousands of commitments to Christ, it is easy to wonder how many of those making such commitments have done so several times before. One informant stated that he had been told that when those making commitments at such rallies are counted there are over 60 million such ‘born agains’ in Kenya in a country with a population of around 30 million. Because so many make a public commitment time and time again.

35

Other groups running large-scale outreach include: African Evangelistic Enterprise (AEE),

Tanzanian Fellowship of Evangelical Students , Campus Crusade for Christ .

36 A feature of the

33 Whittaker, C. Reinhard Bonnke: A Passion for the Gospel , (1998), p 182.

34 Whittaker, C. Reinhard Bonnke: A Passion for the Gospel , (1998), p 125. Bonnke seems to enjoy meeting national leaders, Whittaker has a page of photographs showing Bonnke greeting heads of state, ‘Evangelist Reinhard Bonnke is well known to many African heads of state and has spoken several times to assembled houses of parliament. He has become a firm friend to many presidents and paupers alike’. The heads of state shown include Sani Abacha of

Nigeria, Idriss Deby of Chad and Daniel arap T. Moi of Kenya. Whittaker, C. Reinhard Bonnke: A Passion for the

Gospel, (1998), opposite p 180.

35 ‘born agains’, name given to those who make a commitment to Christ and are seen as having been born again. In

Kenya it is used to differentiate between members of the established mainstream churches and those from

Pentecostal churches. The informant was Stephen Ndoria, student at St. Paul’s United Theological College, in class discussions March 2004.

36 Mlahagwa, J.R. “Contending for the Faith: Spiritual Revival & the Fellowship Church in Tanzania” (1999), p 303.

11 speakers at some of these meetings is the “trend of being aggressive toward other religions”.

37

Muslims have found this approach offensive and threatening.

The patterns of Public Rallies for Christian Outreach in Dar es Salaam and major towns in

Tanzania are similar to those found in Nairobi and in other urban settings in Kenya. Shorter and

Njiru comment on the increase of street preachers after independence in Kenya:

[A] tradition of street-preaching developed in Nairobi and other towns … From the 1960s onwards, urban street preaching gathered momentum, until ot became commonplace. The growth of street preaching was also linked to the growth of urban populations, and particularly to the numbers of industrial and office workers who provided the main audiences in their lunch hour.

38

Walk through Nairobi at lunch-time on any weekday and one sees street preachers actively presenting their message, to anyone who will listen. The preachers are mainly Christians, but not exclusively so.

Another factor in current evangelism is the use of radio and television by evangelists. In

Kenya the state broadcasting channel, Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) and Family TV both regularly broadcast evangelists. Family TV has a regular lunch-time spot featuring Bennie

Hinn, who also visits and holds rallies. Two regular ‘tele-evangelists’ are Bishop Margaret

Wanjiru of Jesus is Alive Ministries and Evangelist Pius Muiru of Maximum Miracle Centre.

Margaret Wanjiru runs a very popular church in the centre of Nairobi and espouses a ‘prosperity gospel’. Galgalo reports, that her sermon:

[D]elivered on the KBC television programme ‘The Glory is Here,’ based on the crucifixion of Jesus. The central core of her application was that Christ’s nailed feet and hands were for the blessing of our hands and feet. And that the holes punctured into

Christ’s hands is the assurance that ‘there can be no holes in our pockets or bank accounts

(sic) because Christ has borne it on our behalf.’ 39

37 Drønen, T. “The Cross and the Crescent in East Africa: An examination of the reasons behind the change in

Christian-Muslim Relations in Tanzania 1984-1994”, Master of Religion Dissertation, Oslo: Unpublished, (1995), p

66.

38 Shorter, A. & Njiru, J.N. 2001 New Religious Movements in Africa , (2001), p 18.

39 Galgalo, J.D. “Impact of Pentecostalism on the Mainline Churches in Kenya”, Encounter 3, (2003), pp 28-42, The sermon was broadcast on 20 th September 2002, endnote 15 p 42.

12

Her approach is very popular but weak theologically and questioned by the main stream churches. Muiru has a regular television spot Kuna Nuru Gizani , (There is Light in the Darkness), with a populist approach.

How far can the methods used in this type of outreach be called “fundamentalist”? If the addresses were to be analysed, often the contents will be found to be dogmatic, using aggressive language, which can foment unrest between Muslims and Christians. In Tanzania, preachers have been told not to preach against other religions in their sermons. This is true for both Christian and

Muslim outreach, as Ludwig comments on Bonnke, and the reason why Muslim preachers

Ngariba and Kawemba from Tanzania were expelled from Kenya, after public meetings held in

Mombasa, was that they were banned on “security grounds” in 1987.

40 Their preaching was seen as being potentially inflammatory, against Christians hence they were expelled on grounds of security.

MUSLIM OUTREACH AND MUSLIM PREACHERS

Muslim outreach ( da‘wa

) has become increasingly visible in recent years, using a variety of methods, some of which are copied from methods used by Christians.

R. Nnyombi writes of the significance of Mombasa in da‘wa

for both Kenya and East Africa as a whole, because of the training given to “religious activist” and as the birthplace of the unregistered Islamic Party of Kenya (IPK).

41 Mombasa is also significant as a centre for publishing

Muslim Tracts and Pamphlets, notably, in the past, by East African Muslim Welfare Association

(EAMWS), nowadays mainly by Adam Traders, many of whose pamphlets are now printed in

40 “Kenya: Provoking Muslim agitation” Impact International 17:23, 27 Nov. (1987), p 5 and Rajab, M. “Nyerere against Islam in Zanzibar and Tanganyika”, (nd), URL http://victorian.fortunecity.com (30.3.99)

41 Nnyombi, R. “Christian-Muslim Relations in Kenya”. Islamochristiana 23, (1997), pp 147-163, p 149 fn 8.

13

India.

42 Other publishers based in Mombasa include: Ahmad M. Ali, Alawiyyah Traders, Ansaar

Muslim Youth Organisation, Shamsudin Haji Mohamed & Co, Sidik Mubarak & Sons,

One reason for the greater level of activity is the arrival of Kenyan graduates from Saudi

Arabia, Sudan, Libya, Tunisia and Egypt, who K.N. Maina says:

Have brought back an intellectual orientation that is generally at variance with the traditional, and often Hadrami, Shafi view of certain religious practices. Wahhabism, in its puritanical, uncompromising and aggressive form has been imported into East Africa by many of these recent graduates.

43

Nnyombi comments that this has brought friction not only between the graduates and traditionalists, but also between them and the followers of other religions especially Christianity.

This in turn has led to polemical public debates ( mihadhara ) in big towns like Nairobi, Mombasa and Nakuru; foreign preachers from Tanzania often conduct these.

44

What is the meaning of the mihadhara , used here in the plural, the word used for these meetings? In Swahili, the dictionary defines mhadhara (singular) as a lecture, public talk, discourse. The word mhadhara appears both in Bosha’s trilingual dictionary and in TUKI; other dictionaries list hadhara - in front of, in the presence of, before, in public.

45 The Arabic word, root hadāra, means to be present, or to present a lecture.

46 Bosha gives the Arabic usage as lecture or discourse .

47 Two Swahili words illustrate its meaning: the verb kuhudhuria

– to attend and the noun mahudhurio

– attendance. If something is to be discussed publicly, it is done hadharani (literally

42 “ Adam Traders ni watumishi wa kutangaza dini kwa njia ya vitabu tangu miaka thalathini za nyuma. Vile vile wahusika na uchapishaji wa vitabu mbali mbali vya dini ya Kiislamu.

” [Adam Traders have served to propagate religion through books for the last thirty years. Likewise they are publishers of various Islamic books]

(Announcement on cover of booklets published by Adam Traders). Translation of Swahili text by author.

43 Maina, K.N. “Christian-Muslim Relations in Kenya”, In Islam in Kenya M. Bakari & S. S. Yahya (Eds.), (1995

Nairobi: ISP), pp 116-141, p 172.

44 Nnyombi, R. “Christian-Muslim Relations in Kenya”, (1997), p 153 fn. 25; p 159 fn. 54.

45 The Swahili- English dictionaries consulted on the meaning of mhadhara are, Bosha, I. The Influence of Arabic

Language on Kiswahili with a Trilingual Dictionary (Swahili-Arabic-English), (1993 Dar es Salaam: Dar es Salaam

University Press), p 150; Taasisi ya Uchunguzi wa Kiswahili (TUKI) 2001 Kamusi ya Kiswahili-Kiingereza, (2001

Dar es Salaam: TUKI), p 201; Johnson, F. A Standard Swahili-English Dictionary, (1939 Nairobi: OUP), p 122 and

Benjamin, M. (Ed.) Living Swahili Dictionary, (1995 New Haven: Yale University), p 71.

46 Cowan, J.M. (Ed.) Arabic-English Dictionary , (1976 Ithaca: Spoken Language Services), p 184.

47 Bosha, I. The Influence of Arabic Language on Kiswahili , (1993), p 150.

14 before an audience). Mhadhara has gained a wider, popular usage for public meetings; this includes meetings for community, political and religious purposes. Any meeting which involves the general public can be called mhadhara ; for instance when an official programme is organised for a visiting dignitary, a mhadhara will be arranged to allow them to speak to the populace as a whole.

It is helpful to examine the development of mihadhara in Tanzania in order to understand their wider use in East Africa, as the Preachers involved are often from Tanzania. Abu Aziz in a deposition to the Attorney General in May 1998 48 states:

Since the adoption in 1984 by Muslim preachers of the method of propagating Islam using comparative religious study, and the corresponding rise of conversions to Islam from

Christianity, the Catholic clergy has been instigating the government to ban Muslim preaching popularly known as “ Mihadhara”

(public debates), alleging that they were defamatory and insulting to Christianity.

49

In January 1998, President Mkapa, speaking at a meeting in Tabora, spoke out against

“People who go about distributing cassettes, booklets and convening meetings where they insulted and ridiculed other religions” 50 Aziz understood this as an open attack only on Muslims, whereas both faith groups have used these methods. The Muslim weekly An Nuur reports such apparent discrimination, when an Assemblies of God Church was given permission to hold a meeting, whilst at the same time the Imam of Chaurembo Mosque was was taken in by the Police for planning a meeting. Muslims were upset by this action which they saw as a clear case of discrimination against them.

51

48 The deposition followed a Police raid and ensuing riot at Mwembechai Mosque, Dar es Salaam in Feb. 1998. A book about this event: Njozi, H.M. Mwembechai Killings and the Political future of Tanzania , (1999 Ottowa: Globalink). The

Appendices to the book include the full text of the Abu Aziz Submission to the Attorney General and the text of letters between the Muslim Council and the President.

49 Aziz, A. “Submission to the Attorney General of Tanzania on the mishandling of the issue of Muslim preaching by the C.C.M. Government”. Dated 15/5/1998 URL: http://www.islamtz.org (10.10.98) p 2.

50 Aziz, A. “Submission to the Attorney General of Tanzania”, (1998), p 2.

51 The Muslim weekly paper An-Nuur reported that mihadhara planned by Muslims continue to be banned “Rais

Mkapa atekeleze hadi yake kwa hadhari”. An-Nuur No.187 February 1999, (30.3.99) URL: http://www.islamtz.org

(30.3.99).. “Imamu ahojiwa na polisi kwa kuandaa mhadhara”. An-Nuur No.197 April 1999, (05.5.99) URL: http://www.islamtz.org .

15

Aziz refers to Muslim preachers using mihadhara from 1984 onwards as a method of presenting “comparative religious study”, without making his meaning clear. Both Smith and

Chande 52 report examples of the ways in which “comparative religious study” is carried out. Chande describes a visit to Tanga, by members of Jumuiya ya Wahubiri wa Kiislamu Tanzania (Society of

Muslim Preachers Tanzania, JUWAKITA), Sheikh Muhammad Ali Kawemba and Sheikh Musa

Fundi Ngariba 53 from Kigoma, Western Tanzania. They spoke at a series of meetings, organised by

Umoja wa Vijana wa Kiislamu Tanzania (Tanzanian Muslim Youth League, UVIKITA) in March

1985:

These public discussions were not intended for Muslims only but were also meant for

Christians with whom the missionaries wanted to enter a dialogue on what the Bible teaches or says as opposed to what Christians believe on such subjects as the divinity of Christ, monotheism versus trinity, monkery (sic) , the Prophet as Paraclete, fasting, dietary regulations and ritual purification. A few times during the question period there were lively exchanges between the missionaries and a few Christians, including a priest. On these occasions the missionaries displayed their skills in polemics. It is obvious that they had taken the trouble to study Christianity and were very familiar with the Bible ... Their aggressive style 54 enchanted the ordinary Tangan but annoyed some Christian representatives who reacted negatively to being challenged in public.

55

Smith describes the meetings, with Kawemba and Ngariba again as speakers, held in Tabora in 1986, which were organised by Baraza Kuu la Waislamu Tanzania (Tanzania Muslim Council,

52 Smith, P. “An Experience of Christian-Muslim Relations in Tanzania”, (1988), AFER 20, pp 106-111 and Chande,

A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and Community Development in Tanzania , (1998 Bethesda: Austin & Winfield).

53 Kawemba and Ngariba (d. 1993) come from Ujiji, their grandfathers came from Zaire Lacunza Balda, J. “Swahili

Islam Continuity and Revival”. Encounter 193-194, March (1993), pp 3-29, p 28. JUWAKITA was proscribed by the Tanzanian government in 1993, Lacunza Balda, J. “Translations of the Quran into Swahili, and contemporary

Islamic Revival in East Africa”, In African Islam and Islam in Africa, D. Westerlund & E.E. Rosander (Eds.), (1997

London: Hurst & Company), pp 95-126, p 99. This group is also linked to Umoja wa Wahubiri wa Kiislam wa

Mlingano wa Dini (Union of Muslim Preachers of Comparative Religions) UWAMDI, Rajab, M. “Nyerere against

Islam in Zanzibar and Tanganyika”, (nd), p12.

54 Chande, A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and Community Development in Tanzania , (1998) in a footnote p 153 fn. 36, Chande refers to this aggressive style of conducting missionary activity as generally associated with the Ahmadis and

Christian missionary groups. Among the Sunnis, the person best known for this style of preaching is ... Ahmad

Deedat. ... In Tanzania Kigoma has been the region of the country that has produced preachers of this kind, including

Ngariba and Kawemba.

55 The preachers were ordered out of Tanga by the local authorities. Later on, they were allowed to return to Tanga, but limited to speaking inside Mosques and not outdoors, Chande, A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and Community Development in

Tanzania , (1998), pp 153, 155.

16

BAKWATA).

56 Local Christian leaders had been specially invited as had party and government officials and Islamic community representatives.

The theme of the lectures ‘The Word of God’ was introduced with the words: there is one

God, one people and one religion. It is unacceptable then that the people in the audience should be of different religions. By the end of the lectures, claimed the speaker, you will see which religion is the religion ordained by God .

57

Smith reports that Ngariba began the lectures by challenging the Christian understanding of the Bible, especially the gospels:

First, Ustadh Ngariba asks:

Where, in the Gospels does Jesus claim to be the Son of God?

Here the argument is that Jesus cannot be called divine in any other way than say, the other prophets and holy men in the Bible. Certainly he cannot be likened to God himself; that would be idolatry. Christians have been misled in their belief of Jesus’ divinity, especially-by

St. Paul.

Secondly,

Where does Jesus tell the people “Be my followers?”

The argument here is that Jesus did not command people to be his followers but, on the contrary, he forbade them. Again St. Paul is portrayed as the arch-villain who induced people to call themselves Christians, at Antioch.

Thirdly,

Ustadh Ngariba explained that Jesus came only for the lost sheep of the House of Israel.

The argument is based on Matthew 10:5 and 19:27 that Jesus came only for those lost sheep and his immediate disciples were sent only to them. Jesus did not come for Africans or

Europeans.

Fourthly,

Several biblical texts, it was claimed, foretold the coming of the Prophet Muhammad, for example Jn 16:12ff.

Jesus was a true prophet who pointed to the coming of Muhammad but the Christians have misrepresented these texts. The intended One who is to come is not the Holy Spirit of

Christian tradition but Muhammad.

.

After … Ustadh Kawemba developed several further points on prayer, fasting, ritual cleansing, and so on. This was intended to show that just as the prophets had performed these rites and practices in a certain way, so did the Islamic community. The Christian community, on the contrary, does not perform these rites in the prescribed way. He asked,

56 BAKWATA was started at the time of the proscribing of East African Muslim Welfare Society (EAMWS) and was described by the first General Secretary, Adam Nasibu, as serving a similar function for Muslims as the

Christian Council of Tanzania (CCT) did for Protestant Christians, Said, M. “Islam and Politics in Tanzania”.

Presented in Nairobi at Da’wah Conference during 1989. Originally published in Al-Haq International , 1989, URL http://www.islamtz.org, (15.11.98), pp 11-12. BAKWATA has generally been viewed as an arm of the government party that was imposed on Muslims, and as such has not been effective in representing Muslims. After Mwinyi became President, BAKWATA found its voice, during 1987 lobbying for the reinstatement of separate Islamic

Courts and arranging Public Debates, Lodhi & Westerlund “African Islam in Tanzania”. In Islam Outside the Arab

World, D. Westerlund & I. Svanberg (Eds.), (1999 London: Curzon Press), pp 97-110, p 104.

57 The emphasis is his, Smith, P. “An Experience of Christian-Muslim Relations in Tanzania”, (1988), AFER 20, pp

106-111, p 107.

17

“on what authority have the Christians changed these?” “Is it not obvious,” he continued

“that only the Muslim community has remained faithful”.

58

The lectures were followed by a question time, when many Christians attempted to respond, but in fact only succeeded in demonstrating the Christians lack of understanding, as the speakers quoted texts to substantiate their position, only to be contradicted by other speakers.

59

Thus both Chande and Smith give an impression of the way in which the Muslim mihadhara concerning “comparative religious studies” are being conducted, engendering inter-faith tension.

The Bible seems to be being used as the means of showing Christians that they have reasons to question their faith. Muslim preachers appear to wish to show the Bible as a “pointer” to the

“correct” way to God, that is, in their view, Islam.

THE INFLUENCE OF AHMED DEEDAT

East African preachers and writers have been influenced by and have followed the approach used by Ahmed Deedat (born 1918).

60 Deedat’s pamphlets began to appear in East

Africa from the 1960s. One example, printed in South Africa in English and widely available is:

58 Smith, P. “An Experience of Christian-Muslim Relations in Tanzania”, (1988), pp 107-108. The section is quoted fully, as it reports a first hand experience of a mhadhara , led by Ngariba and Kawemba and Smith’s informed critique. Ngariba and Kawemba published a short booklet with pp. 33 + iv in 1987 in English entitled Islam in the Bible also in Swahili Uislamu katika Biblia

. The final paragraph of the Preface, written by A.S. Suleiman, says “Their lectures have been compressed into this small booklet for the benefit of those who have not had the opportunity to listen to them”

(iv). Lacunza Balda regards this pamphlet as being in the style of Deedat, Lacunza Balda, J. “Swahili Islam Continuity and Revival”, (1993), pp 3-29, p 28. The opening statement of the text in the Swahili version of the booklet, but not in the English version, is headed: “

Mungu Mmoja Dini Moja

” (One God One Religion), both state “Muslims are wondering why there is more than one religion”, Ngariba, M.F. & Kawemba, M.A. Islam in the Bible , (1987 Zanzibar: Al-

Khayria Press Ltd), p 1; Ngariba, M.F. & Kawemba, M.A. Uislam katika Biblia , (1987 Zanzibar: Al-Khayria Press

Ltd).

59 Smith, P. “An Experience of Christian-Muslim Relations in Tanzania”, (1988), p 108.

60 Deedat was born in India, but moved to South Africa in 1927. His supporters date his zeal from 1936 when, whilst working in a store, he was stung by the insults against Islam by trainee Christian missionaries. He obtained a copy of

Izhar-ul-Haq (The Truth Revealed) and used this to debate with the trainee missionaries. From this, he went on to write booklets challenging the truth of the Bible and Christianity, and to hold debates with Christian Evangelists throughout the world. His populist polemical style has been well received by many Muslims, Lockhat, E. Ahmad

Deedat” Biographical Article dated 25 June 1994, URL http://home.virtual-pc.com (9.6.99), pp 1-2.

18

Muhammad (PBUH) in the Old and New Testaments. Lacunza Balda refers to a Swahili translation of this text, Mtume Muhammad katika Biblia (The Apostle Muhammad in the Bible), dated 1965.

61 Arye Oded states that:

Islamic propaganda also reached Kenya from the Islamic Propagation Centre in Durban,

South Africa, which disseminated pamphlets about Islam, such as What the Bible Says about Muhammad , which was reprinted in Nairobi and distributed by the Jamia Mosque of Nairobi”.

62

In addition to printed material, audiocassettes and, more recently, videos of Deedat’s debates and talks are popular and have been widely distributed in East Africa.

Ngariba and Kawemba published Islam and the Bible in 1987, in English and Swahili, at a time when they were involved in a series of mihadhara (public meetings) concerning the Word of

God. Justo Lacunza Balda regards Ngariba as: “following in the footsteps of Deedat”.

63 Hamza

Njozi, in his book, Mwembechai Killings and the Political Future of Tanzania, describes how in

June 1981, as Secretary General of the Muslim Students Association of the University of Dar es

Salaam (MSAUD), he invited Ahmed Deedat to speak at a conference in Dar es Salaam, where he gave a lecture on Muhammad in the Bible.

64 This was significant as it meant that a considerable number of young educated Muslims were able to see at first hand the methods and effectiveness of Deedat’s approach. So it is not surprising that after a short time his methods came to be used in mihadhara .

65

61

Other Deedat pamphlets that have been translated into Swahili include: Biblia Asema nini juu ya Muhammad

(S.A.W.) (What does the Bible say about Muhammad (P.B.U.H.)), dated 1988, Lacunza Balda, J. “Translations of the Quran into Swahili, and contemporary Islamic Revival in East Africa”, (1997), p 101; Adam Traders list several titles Uislamu katika Biblia (Islam in the Bible); Je! Yesu Alisulubiwa? (Was Jesus Crucified?).

62 Oded, A. Islam and Politics in Kenya, (2000 London: Lynne Rienner Publishers Inc.), p 113.

63 Lacunza Balda, J. “Translations of the Quran into Swahili, and contemporary Islamic Revival in East Africa”,

(1997), p 101.

64 Njozi, H.M. Mwembechai Killings and the Political Future of Tanzania , (1999), pp 11-12, reported that after the first lecture 6 Catholic seminarians embraced Islam and that pressure was put on MSAUD to cancel the second lecture – following a letter to the leadership of Bakwata by both TEC (Tanzanian Episcopal Conference) and CCT.

Njozi reports that he went to the Vice-President to request him to allow the meeting to go ahead. As a result of the meeting 4 Christians embraced Islam.

65 This is reflected in Njozi, who became a lecturer at the University of Dar es Salaam and in Mohamed Said and the

19

The comparative religious studies approach used in mihadhara is aimed at challenging the preconceived views of Christians concerning their own faith. Certainly it is difficult for a listener not to want to respond to the statements that are given by the speakers. Cuthbert Omari comments on the participation of Christian fundamentalists in mihadhara with Muslims:

Some of those Christians even accepted the idea of a public debate with Muslims on certain biblical and doctrinal passages. However they were a failure for Christians because the

Muslims who took part in the debates were well prepared and made the Christians with their fundamentalist attitudes look ignorant and foolish before the audience.

66

Omari’s view is borne out by others. The preparations and knowledge of the Bible shown by the speakers often exceeds that of the Christians who try to respond. Smith echoes this in his report on the Tabora meetings and the way in which a Bible text was interpreted differently by the

Christians who were trying to respond.

67 These fundamentalist Christians believe that they will be led by the Holy Spirit to give the right and convincing response. They eschew formal Theological education and academic study.

68 The ‘failure’ is there because the Muslim Preachers have prepared themselves and know the texts they use. The Muslim Preachers also know suitable ripostes, with which they can ‘put down’ Christian questioners, which emphasises the lack of knowledge of the

Christian. It has also been observed from listening to audio-cassettes of mihadhara that in some cases Christians are questioned in a way that seems to confuse them and leads them to respond in a foolish manner that can at times be used to embarrass them.

69 Watching a video recording of Ngariba members of the Muslim Writers Workshop who are discussed below.

66 Omari, C.K. “Christian-Muslim Relations in Tanzania”, in J.P. Rajashekar (Ed.), Christian-Muslim Relations in

Eastern Africa , (1988 Geneva, Lutheran World Federation), pp 61-68, p 66.

67 Smith, P. “An Experience of Christian-Muslim Relations in Tanzania”, (1988), p 108.

68 From sixteen years of teaching in Christian theological Seminaries in East Africa, the writer can say that these students often divorce the ‘head knowledge’ of the lecture room, which is needed to pass exams. and the ‘heart knowledge’ given by God, through the Holy Spirit that they preach.

69 This tendency has been also been observed with Deedat and the debates he held with Christians. When he debated with Josh Mac Dowell in London in 1986, the Chairperson began by asking that the audience should not cheer for one side or the other. However once the debate got under way the “point-scoring” remarks made by Deedat were loudly cheered. This tendency is also evident with the editing of the Video-cassettes; an example is the Deedat vs.

Jimmy Swaggart debate which is edited with the “errors” and blasphemies made by Swaggart highlighted. In fact they are reprised at the end of the debate, presumably in order to help others to know how best to “attack” the approach used by Swaggart.

20 preaching in Dar es Salaam, he was able to speak for over an hour, with no recourse to notes or to a

Bible.

Aziz reports on the success of mihadhara in converting Christians, some of them priests. He regards this success as being one of the reasons for the government seeking to ban Muslim preaching at the instigation of the Roman Catholic Church, because “it was blasphemous and insulting to Christianity … and a threat to the peace of Tanzania”.

70

We have examined how mihadhara have been used in Tanzania and described the present sensitive situation there, with permission being refused for mihadhara , and when they are held, the meetings are often shut down by the authorities.

71 However mihadhara are still taking place: a group

Al-Mallid is now increasingly active. The Muslim newspaper, An-Nuur 72 reports that the group held mihadhara in Mwanza during 1999 and also in Burundi.

73

Similar methods are still being used in the mihadhara held in various parts of Kenya. In

2002 as part of a Vacation Programme on Islam, 74 Muslim speakers were invited to address the course on Muslim-Christian Relations. This was arranged through the Jamia Mosque in Central

Nairobi. Three speakers came, one the Chief Kadhi of Nairobi, another was the da’i

75 from the

70 Aziz, A. “Submission to the Attorney General of Tanzania on the mishandling of the issue of Muslim preaching by the C.C.M. Government”, dated 15/5/1998 URL: http://www.islamtz.org (10.10.98), p 12.

71 Mihadhara are still continuing. In March 2000, in Kongwa, Tanzania, a week of meetings was held, organised by the local Mosque, with a speaker, a former Christian (who had reportedly worked for the Bible Society) speaking and condemning Christian practices. An-Nuur (No. 247), reports a Court Case in Morogoro, Tanzania, against a Muslim group, Al-Mallid , who had held a Mhadhara without permission. The CID Officer whilst giving evidence is also reported as wanting to arrest the publishers and sellers of the Qur’ān, as it slanders other faiths. An-Nuur No. 247,

(2000), URL: http://www.islamtz.org/an-nuur2/247 (28.4.00).

72 An-Nuur is a weekly newspaper, published in Dar es Salaam, in Swahili.

73 An Nuur nos. 202 & 203 contain reports concerning mihadhara , that the Police had arrested participants because of kashfa za dini (religious slander) and preaching from the Bible. One group in Nzega stated that they had led 26 prisoners to Islam whilst they were on remand for preaching. The report on Burundi states that several hundred have

“returned to Islam”. An-Nuur No. 202 (1999), URL: http://www.islamtz.org/an-nuur2/202 (28.7.00) and An-Nuur

No. 203, (1999), URL: http://www.islamtz.org/an-nuur2/203 (28.7.00)

74 This was held at St. Paul’s United Theological College, Limuru. Around 40 people attended the session.

75 da’i (rarely, da’iya ), “he who summons” to the true faith, a title used among several Muslim groups for their chief propagandists, Hodgson, M.G.S. “ da’i ” in Encyclopaedia of Islam CD-ROM Edition v. 1.0 Leiden: Brill, II, (1999), p 97b. In the case of the da’i referred to, he appeared to be fulfilling the role of Education officer at the Jamia

Mosque.

21

Jamia Mosque and the third was a Preacher from the Muslim Preachers Association . In discussions with him, it became clear that he came from Mwanza, in Tanzania, but was working in Nakuru, Kenya. When invited to speak, he chose to demonstrate the Comparative Religious

Studies approach, and for about half an hour he spoke using the Bible to demonstrate the truths of

Islam, this was done in Swahili, which then had to be translated. This short demonstration clearly showed that the methods used by Ahmed Deedat and propagated by Ngariba and Kawemba are still being followed, even to the ways that verses are interpreted. It also showed that mihadhara are seen as an effective method of propagation. It is not clear that the ways which Taylor and other Christian missionaries in the 19 th

century carried out open air preaching, and their use of the bible, as described above, has had any significant effect on the content and interpretation of the bible used by present day Muslim Preachers.

MUSLIM WRITERS’ WORKSHOP (WARSHA)

The Muslim Preachers who are involved in da‘wa

and mihadhara have influenced many young Muslims, who are now writing 76 and developing outreach strategies based on the methods that they have observed. One group of young Muslims was “awakened” to the vitality of Islam by the teachings of an expatriate Pakistani during the 1960s and 1970s. It is this group that we now examine.

Warsha ya Waandishi wa Kiislam (Muslim Writers’ Workshop), popularly known as

Warsha , comprises a small group of Muslim intellectuals, including Mohamed Said. Mohamed

Said was born in 1952 and has a BA in Political Science from the University of Dar es Salaam.

76 The MA dissertation by the author, “Muslim Affirmation through Refutation: A Tanzanian Example”,

Birmingham 1999, is a translation and study of a pamphlet in Swahili which used the Bible (250 references) to try to

22

He can be seen as the most prominent member of the original Warsha , having had several articles published and a book in 1998, The Life and Times of Abdulwahid Sykes (1924-1968): The untold

Story of the Muslim Struggle against British Colonialism in Tanganyika , which was published in

1998. This is an example of a style of writing that can be best described as “revisionist histories”.

77 Presently they are based at Quba Mosque in Dar es Salaam. From where they run a secondary school, arrange courses, publish literature and issue statements on matters of public concern (mainly concerned with education and economics).

78 Warsha is concerned in effecting reform of the teaching at Qur’anic Schools, which still mainly consists of the rote learning and memorising of parts of the Qur’ān.

79 demonstrate the truth of Islam.

77 Mohamed Said has had several articles, which he describes as research articles, Said, M. The life and times of

Abdulwahid Sykes (1924-1968) , (1998 London: Minerva Press), p viii, published in Africa Events and New African in

1988 and 1989. Two longer articles written by him appear on the Islam in Tanzania Webpages. These are copies of articles published in 1989 and 1993. In the preface of the book it says of him: “He has conducted research on political history of Tanganyika hitherto considered as conclusive[,] uncovering that significant part omitted in the official history. The author came into prominence in the late 1980s through his revelations and thought provoking articles on the central role of Islam in the struggle against colonialism in Tanganyika and the marginalisation of

Muslims by successive post-independence governments, a subject which until then was considered a taboo”, Said,

M. The life and times of Abdulwahid Sykes (1924-1968) , (1998) pp vii-viii. Smith, P. “Christianity and Islam in

Tanzania: Development and Relationships”, (1990), Islamochristiana 16, pp 171-182, p 176, citing an article by

Said, “In Praise of Our Ancestors” Africa Events March/April 1988, refers to revisionist histories being attempted today which are trying to show these early movements in support of TANU as Islamic Movements. Said’s response to the accusation of being revisionist is to quote the Party Archives showing that the TANU Elders Council under

Sheikh Suleiman Takadir had 173 members all of whom were Muslims, Said, M. The life and times of Abdulwahid

Sykes (1924-1968), 1998 p 338). Other articles by Said are: 1988 a “In Praise of Ancestors”. Africa Events

March/April 1988, pp 37-42; 1988 b “Founder of a Political Movement”. Africa Events September (1988), pp 38-41;

1989 a “Islam and Politics in Tanzania”. Presented in Nairobi at Da’wah

Conference during 1989. Originally published in Al-Haq International 1989 URL http://www.islamtz.org (15.11.98); 1989 b “Tanzania’s Religious

Politics”. New African November 1989, p 35; 1993 “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania: The Question of Muslim

Stagnation in Education”. Originally published in Change 1993 URL http://www.islamtz.org/nyaraka/Elimu2.html

(15.11.98). The paper by Chesworth, J. “Inter Faith Relations. What hope do we have?”, 2001, Paper presented at

EATWOT Kenya Chapter Meeting, St. Mary’s Centre, Nakuru, Kenya, examines the issue of “revisionist histories”.

In 2001, Said was working for the Port Authority in Tanga.

78 Lodhi, A.Y. & Westerlund D. “African Islam in Tanzania”, In Islam Outside the Arab World , (1999), p 106, and

Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania: The Question of Muslim Stagnation in Education”, (1993), p 17.

Warsha has produced several books of Islamic Education: Mafundisho ya Qur’an (Teachings of the Qur’ān), published by the Islamic Foundation, Nairobi; Uchumi katika Uislamu (Economics within Islam) condemning

Tanzanian Socialism and proposing an Islamic model; and The True Way of Life , living in accordance with a fundamentalist interpretation of the sharī‘a.

According to Smith, P. “Christianity and Islam in Tanzania:

Development and Relationships”, (1990), p 181, it is the aim of Warsha to make this the way of life in Tanzania.

79 Lodhi, A.Y. & Westerlund D. “African Islam in Tanzania”, In Islam Outside the Arab World , (1999), p 106.

23

Although Warsha is based in Dar es Salaam, its influence is more widespread. It claims to have a considerable following amongst the 20-40 age group of Muslims.

80 A.N. Chande reports that “it makes its presence felt in the major urban centres in the country through its writings which have appealed to a segment of the youth”.

81

EXTERNAL INFLUENCES: MUHAMMAD HUSSEIN MALIK AND WARSHA

How did Warsha begin as an organisation? Its origins can be traced back to an expatriate teacher on a government contract. In 1964 Muhammad Hussein Malik, 82 a Pakistani, came to

Tanzania to teach Mathematics at Secondary School level in Dar es Salaam.

83 Malik, in addition to his official teaching duties, volunteered to teach Islamic Studies 84 in all Secondary Schools in

Dar es Salaam and surrounding areas.

85 Malik’s teaching of Islam was seen as revolutionary in the context of Tanzania. The effect was to enable a group of young Muslims “to understand itself and be aware of the anti-Muslim force against Islam”.

86

Said explains the method that Malik used in teaching Islamic Studies:

Dr. Malik began first by helping his students overcome the inferiority complex which was a result of colonial propaganda and histories taught in schools. Muslim students were taught of scientific achievement and accomplishment of Muslim scholars of the past and present. ... He taught a contrasting history of Islam as a religion which did not begin with

Muhammad (PBUH), but with Adam. Dr. Malik taught his way down to the time of Jesus and the Jews, emphasising the fact that Jesus like Muhammad was a Muslim. His most interesting and captivating topic was the history of the Jews how they turned religion into

80 Sicard, S. von “Islam in Tanzania”, CSIC Papers No. 5 September, (1991), pp 1-13, p 10.

81 Chande, A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and Community Development in Tanzania , (1998), p 255.

82 Said gives Malik the honorifics of Doctor and Professor in his article, “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania: The

Question of Muslim Stagnation in Education”, Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”, (1993), p 5.

83 Rajab, M. “Nyerere against Islam in Zanzibar and Tanganyika”, (nd), p 9; Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in

Tanzania”, (1993), p 5.

84 All Secondary Schools have a weekly time-tabled Religious Education ( dini ) period, usually taught by local clergy or accredited lay worker to their own faith group.

85 Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”, (1993), p 5.

86 Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”, (1993), p 5.

24 nationality and vice-versa. He concluded his course by showing the imprecision in

Christianity.

87

It seems that Malik’s approach to the teaching of Islam came as a “breath of fresh air” to the young Muslims, used to the rote learning of the Qur’anic Schools. In an interview with

Chande, Malik said that he had had connections with Abul A‘lā Maudūdī’s

Jamā‘at-i Islāmi

(Party of Islam) “which had shaped his understanding of Islam as a religion and code of conduct in life”.

88 Malik exposed the students to the teachings of Maudūdī 89 and Sayyid Qutb.

90 This gave them a greater awareness of Islam and its place in the world.

The Islamic Foundation has published several works by both Maudūdī and Qutb, their office in Nairobi has published some in Swahili as well as English. For Maudūdī: Towards

Understanding Islam, Katika Kuu (sic) Fahamu Islamu; Islamic Way of Life, Mpango wa Maisha

Katika Uislamu; In English

Fundamentals of Islam; The Meaning of the Qur’an; What Islam stands for; Qadiani Problem; In Swahili Muongozo wa Ibada Katika Uislamu (Guide to Worship in Islam), Ndia (sic) ya Amani na Uokofu (Way of Peace and Salvation). For Qutb in Swahili his

Utume wa Mohamed (The Servanthood of Muhammad). The Islamic Foundation bookshop in

Nairobi, also stocks several titles published by the Islamic Foundation in the United Kingdom,

87 Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”, (1993), p 6.

88 Chande, A.N. Islam, Islamic Leadership and Community Development in Tanga, Tanzania, PhD Thesis, McGill

University Montreal, (1991), p 231.

89 Maudūdī, Indian by birth, founded the

Jamā‘at-i Islāmi,

in 1940. After partition he campaigned for the establishment of a truly Islamic State and society in Pakistan. He was imprisoned by the Pakistan government and sentenced to death (1953) then released. He wrote many books, which have been influential throughout the Muslim community. These include Tafhīm al-Qur’ān, his translation of the Qur’ān into Urdu with a commentary. Aziz

Ahmad says:

Jamā‘at-i Islāmi

fundamentalism is the complete antithesis of liberal modernism and vests all rights of legislation immutably in God alone, denying them to all human agencies, individual or collective, thus preaching a theocracy which is to be run by the consensus of the believers according to the letter of the revealed law, Ahmad, A.

“ djam‘iyya in India and Pakistan” In Encyclopaedia of Islam CD-ROM, II, p 428b (1999, Leiden: Brill).

90 Qutb, an Egyptian who was active with the Muslim Brotherhood, was executed in 1966 by the government for seditious activities. He wrote several books, notably Signposts. Tamimi reports on the link between Qutb and

Maudūdī: that Qutb drew from the theories of Maudūdī especially concerning the reversion of Islam to a state of jāhiliyya (ignorance) . However Qutb went further than Maudūdī in his rejection of democracy Tamimi, A.

“Democracy in Islamic Political Thought”,

Encounters 3:1 (1997), pp 21-44, p 32. For references by Malik to

Maudūdī and Qutb, see Chande, A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and Community Development in Tanzania , (1998), p 144;

Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania: The Question of Muslim Stagnation in Education”, (1993), pp 4-5.

25 especially the Quranic commentaries, Tafhīm al-Qur’ān by Maudūdī and fi izilal al Qu’rān by

Qutb, as well as titles published by others such as Qutb’s Signposts . It is perhaps too soon to assess how influential the availability of their books in Swahili has been. However, it seems clear that Malik was one of the first to use their ideas in teaching in East Africa.

Chande relates in his interview with Malik the approach that he used:

[He] concentrated his efforts on the Muslim youth since this group was a fertile ground with which he could work to create a new Muslim awareness. His technique was to teach his students not so much about fiqh (legal matters), but about the basic principles or philosophy of Islam. He inspired in his students an understanding of Islam that went beyond mere religious dogma, that is, Islam as a complete way of life. This type of teaching moulded the thinking of the Muslim youth in Warsha in an activistic direction.

91

Said in his writing clearly shows the debt that he and others owe to Malik:

In a period of ten years Dr. Malik was able to mould a strong following of disciplined and committed young men who began to see the injustices committed to Muslims in the

Tanzanian society. Dr. Malik’s teachings went beyond schools, he made rounds of mosques to lecture on different topics with his students interpreting for him. Once free of complex[es] and armed with the teachings of [the] correct version of Islam as a superior culture to any other, Dr. Malik laid a heavy burden on his students that they have an obligation to change the society and restore back the honour denied Islam and Muslims not only in Tanzania but throughout the world.

92

The influence of Maudūdī seems to be apparent in the approach used by Malik. It also seems clear in the writings of Warsha . Uchumi katika Uislamu (Economics within Islam), 93 The True

Way of Life and

Mafundisho ya Qur’an

(Teachings of the Qur’ān) all show Maudūdī’s ideas, with an emphasis on the Qur’ān, the application of sharī‘a and the rejection of religious pluralism.

94

Malik’s students took his teachings and began applying them in Tanzania. By the mid-1970s they began to enter tertiary education and became active in student politics. In particular they joined the Muslim Students Association of the University of Dar es Salaam

91 Chande, A.N. Islam , Islamic Leadership and Community Development in Tanga, Tanzania , (1991), pp 231-232.

92 Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”, (1993), pp 6-7.

93 Chande states that the Warsha booklet Uchumi is inspired by ideas from the writings of Maudūdī, Chande, A.N.

Islam, Ulamaa and Community Development in Tanzania , (1998), p 148.

94 Ruthven, M. Islam in the World , (1984 London: Penguin), p 327.

26

(MSAUD), which became very active under the influence of Warsha members.

95 They also spread the message of Islamic activism to others.

They ... started to work on ways to change the leadership of BAKWATA to transform it from a puppet organisation under the influence of the Christian lobby to an effective

Muslim institution to represent Muslim interests.

96

Rajab expresses the opinion that Malik “played a formative rôle in the ideological development of Muslim youths in Tanganyika and formed [ Warsha ] in 1975”.

97

Initially, a group of around eight members would meet on Sundays to write together.

98

Lodhi and Westerlund say that it had many young and well-educated members, some of whom were Shi‘ah.

99 Said says that they deliberately operated without seeking registration and without making their leadership apparent, in order to avoid problems.

100

WARSHA AND BAKWATA

BAKWATA ( Baraza Kuu la Waislamu Tanzania , Tanzania Muslim Council) was viewed with suspicion by many Muslims. A change occurred when, in the late 1970s, a Muslim lawyer,

Sheikh Muhammad Ali, originally from Tanga but working in Dar es Salaam, became Secretary.

Warsha members began to occupy various positions in BAKWATA. In the light of his influence

95 Both Mohamed Said and Hamza Njozi were members of MSAUD, Njozi being General Secretary in 1981, Njozi,

H.M. Mwembechai Killings and the Political Future of Tanzania , (1999), pp 11-12.

96 Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”. (1993), pp 8-9. Both Said and Rajab regard the governing political party Chama cha Mapinduzi (Revolutionary Party) (CCM) as in the thrall of Christians. Rajab is a Zanzibari

Muslim activist, whose polemical anti-Christian writings can be accessed via the Islam in Tanzania Webpages. Rajab calls CCM the Christian Church Movement, Rajab, M. “Nyerere against Islam in Zanzibar and Tanganyika” p 12, and in the context of the arrival of the Portuguese in 1498, the Catholic Crusade Movement, Rajab, M. “Islam and the Catholic Crusade Movement in Zanzibar”, (nd), URL http://victorian.fortunecity.com, (30.3.99), p 3.

97 Rajab, M. “Nyerere against Islam in Zanzibar and Tanganyika”, (nd), p 9.

98 Chande, A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and Community Development in Tanzania , (1998), p 144. Said says this of Warsha

“From the quality of the papers it published and distributed to Muslims there can be no doubt whatsoever that [the] authors were highly educated, Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”, (1993), p 9.

99 Lodhi, A.Y. & Westerlund, D. “African Islam in Tanzania”, In Islam Outside the Arab World , (1999), p 106.

100 Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”, (1993), p 8. The logic seems to be, if you are not registered you cannot have your registration cancelled.

27 with Muslim youth, it is not surprising to find that when Malik finished his teaching contract with the government the door was open for him to start working for BAKWATA.

Having gained some influence within BAKWATA, Warsha conducted research as to why

Muslim students were lagging behind in education and published a report in December 1981

‘

Umuhimu wa kuwa na Seminari za Kiislamu

’ (The Importance of Establishing Islamic

Seminaries). BAKWATA was running four schools, 101 which had originally been started by

EAMWS (East African Muslim Welfare Society). Warsha regarded the way they were run, offering secular education and being in effect profit-making projects, as wrong. BAKWATA got permission from the Ministry of Education for three of the schools to become Muslim

Seminaries.

Recruitment for new staff was carried out and members of Warsha were able to gain most of the posts.

102

The environment of the Seminaries was Islamic in order that pupils should acquire both modern education and Islamic religious teachings. The Islamic environment aimed at in the seminaries was one where times of prayer, Islamic dress code and behaviour were followed.

103

Religious teaching was seen as a means of fostering the moral values of the youth. For this purpose, a number of religious text books were produced by Kinondoni Muslim Seminary to be used for the teaching of the new subjects. These new subjects included Qur’anic Studies, Arabic,

Islamic History and Fiqh . The books were published in 1982, Mafunzo ya Elimu ya Dini ya

Kiislamu wa Shule za Sekondari I-IV (Teaching of Religious Education for Secondary Schools I-

101 Two of the schools were Kinondoni in Dar es Salaam and Jumuiya in Tanga, Chande, A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and

Community Development in Tanzania , (1998), p 144.

102 Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”, (1993), p 10.

103 The introduction of Islamic dress in particular, has become an issue in schools in East Africa. In Kenya schools have been taken to court over the refusal to allow girls to wear headscarves.

28

IV) .

104 Malik became closely associated with Kinondoni and his son was installed as headmaster, to help shape the character of the new school.

105

BAKWATA began publishing a monthly newsletter Muislamu (Muslim); the first issue came out in May 1981. Warsha was involved with this project, its members forming the Editorial

Board. Articles included teachings of the Qur’ān, the purpose of Hajj and dietary rules.

BAKWATA was also responsible for producing programmes for Radio Tanzania. These were broadcast every Friday. Warsha took over the production of these. They reduced the playing of recordings of kasida (Religious Poems) and dhikiri (Sufi litanies); they aimed to broadcast programmes which carried a “special message” to Muslims. Malik had a slot on a morning programme, which created interest amongst educated Muslims.

106

It was around this time that Warsha wrote a series of books Mafundisho ya Qur’an concerning each of the Pillars of Faith of Islam. These were published by the Islamic Foundation in Nairobi between 1982 and 1985.

107

During 1982, events occurred which led to the ejection of Warsha and all its members from BAKWATA. Said regards the events leading to

Warsha’s expulsion as being a government inspired plot to isolate them from Muslims in order to prevent them from making any further revelations about the mistreatment of Muslims.

108

Sheikh Muhammad Ali, as secretary of BAKWATA, was taken to task for allowing the organisation to be hijacked by “hot-headed youths”. Warsha was accused of being

104 Chande, A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and Community Development in Tanzania , (1998), p 146.

105 Chande, A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and Community Development in Tanzania , (1998), p 235.

106 Said, M. “Intricacies and Intrigues in Tanzania”, (1993), p 11; Chande, A.N. Islam, Ulamaa and Community