what is deviance - Mr. Hotopp's Wiki

advertisement

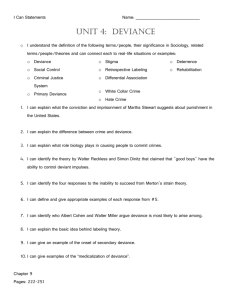

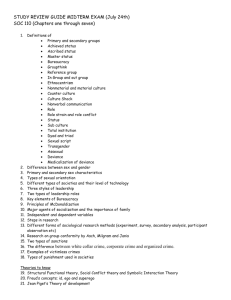

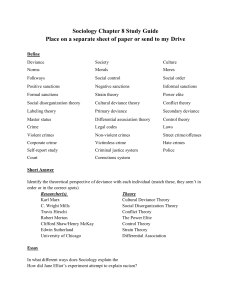

WHAT IS DEVIANCE? Deviance is the recognized violation of cultural norms. One familiar type of deviance is crime, or the violation of a society's formally enacted criminal law. Deviant people are subject to social control, or the means by which members of a society try to influence each other's behavior. A more formal and multifaceted system of social control, the criminal justice system, refers to a formal response by police, courts, and prison officials to alleged violations of the law. The Biological Context During the later part of the nineteenth century, Caesare Lombroso, an Italian physician who worked in prisons, suggested that criminals have distinctive physical traits. During the middle of twentieth century, William Sheldon suggested that body structure was a critical link to criminal behavior. Subsequent research by Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck supported this argument; however, they suggested body structure was not the cause of the delinquency. The field of genetics has rejuvenated interest in the study of biological causes of criminality. Overall, research findings suggest genetic and social influences are significant in affecting the patterns of deviant behavior in society. Personality Factors Psychological explanations of deviance concentrate on individual abnormalities. Weaknesses in psychological research are pointed out. The Social Foundations of Deviance Both conformity and deviance are shaped by society. This is evident in three ways: (1) deviance varies according to cultural norms; (2) people become deviant as others define them that way; and (3) both norms and the way people define situations involve social power. THE FUNCTIONS OF DEVIANCE: STRUCTURAL-FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS Durkheim’s Basic Insight Emile Durkheim asserted that deviance is an integral part of all societies and serves four major functions. These include: (1) affirming cultural values and norms, (2) clarifying moral boundaries, (3) promoting social unity, and (4) encouraging social change. Merton's Strain Theory According to Robert Merton, deviance is encouraged by the day-to-day operation of society. Analysis using this theory points out imbalances between socially endorsed means available to different groups of people and the widely held goals and values of society makes some people prone to anomie. This leads to higher proportions of deviance in those groups experiencing anomie. Four adaptive strategies are identified by Merton: innovation, ritualism, retreatism, and rebellion. Figure 6-1 (p. 137) outlines the components of this theory. Deviant Subcultures Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin have attempted to extend the work of Merton utilizing the concept of relative opportunity structure. They argue that criminal deviance occurs when there is limited opportunity to achieve success. They further suggest that criminal subcultures emerge to organize and expand systems of deviance. Albert Cohen found that deviant subcultures occur more often in the lower classes and are based on values that oppose the dominant culture. Walter Miller argued that the values that emerge are not a reaction against the middle-class way of life. Rather, he suggested that their values emerge out of daily experiences within the context of limited opportunities. He described six focal concerns of these delinquent subcultures--trouble, toughness, smartness, excitement, fate, and freedom. Three limitations of the functionalist approach are pointed out. First, functionalists assume a single, dominant culture. Second, the assumption that deviance occurs primarily among the poor is a weakness of subcultural theories. Third, the view that the definition of being deviant will be applied to all who violate norms is inadequate. LABELING DEVIANCE: THE SYMBOLIC-INTERACTION APPROACH The symbolic-interaction paradigm focuses on how people define deviance in everyday situations. Labeling theory, the assertion that deviance and conformity result, not so much from what people do, as from how others respond to those actions, stresses the relativity of deviance. Primary and Secondary Deviance Edwin Lemert has distinguished between the concepts of primary deviance, relating to activity that is initially defined as deviant, and secondary deviance, corresponding to a person who accepts the label of deviant. Stigma Erving Goffman suggested secondary deviance is the beginning of a deviant career. This typically results as a consequence of acquiring a stigma, or a powerfully negative label that greatly changes a person's self-concept and social identity. Some people may go through a degradation ceremony, like a criminal prosecution. Retrospective labeling is the reinterpretation of someone's past consistent with present deviance. Projective labeling unfairly uses present deviance to evaluate future actions. Labeling and Mental Illness Thomas Szaz has argued that the concept "mental illness" should no longer be applied to people. He says that only the "body" can become ill and therefore mental illness is a myth. He argues that this concept is applied to people who are different and who jeopardize the status quo of society. It acts as a justification for forcing people to comply to cultural norms. The label of mental illness becomes an extremely powerful stigma and can act as a selffulfilling prophecy. The Medicalization of Deviance The medicalization of deviance relates to the transformation of moral and legal deviance into a medical condition. Our society's view of alcoholism in recent years is a good illustration of this process. Whichever approach is used, moral or medical, will have considerable consequences for those labeled as deviant. Sutherland's Differential Association Theory Edwin Sutherland suggests that deviance is learned through association with others who encourage violating norms. This is known as the differential association theory. Survey research supports this view. Hirschi's Control Theory Travis Hirschi pointed out that what requires explanation is conformity. He suggested conformity results from four types of social controls: attachment, opportunity, involvement, and belief. Limitations of the social-interaction approach concern a lack of focus on why society defines certain behavior as deviant and other behavior as not deviant. Unlike other theories, which focus on the act of violence, the focus of labeling theory is on the reaction of people to perceived deviance. This theory provides a relativistic view of deviance and overlooks certain inconsistencies in the actual consequences of deviant labeling. Further, the assumption that all people resist the deviant label and the fact that there is limited research on actual response patterns of members of society to people labeled as deviant are weaknesses to this approach. DEVIANCE AND INEQUALITY: SOCIAL-CONFLICT ANALYSIS Deviance and Power Social inequality serves as the basis of the social-conflict theory as it relates to deviance. Certain less powerful people in society tend to be defined as deviant. This pattern is explained in three ways. First, the norms of society generally reflect the interests of the status quo. Second, even if the behavior of the powerful is questioned they have the resources to resist deviant labels. And third, laws and norms are usually not questioned as being inherently unfair; they are viewed as "natural." Deviance and Capitalism Steven Spitzer suggested that deviant labels are attached to people who interfere with capitalism. Four qualities of capitalism are critical in determining who is labeled as deviant. This list includes: private ownership, productive labor, respect for authority, and acceptance of the status quo. White-Collar Crime The concept white-collar crime, or crimes committed by people of high social position in the course of their occupations, was defined by Edwin Sutherland in the 1940s. While it is estimated that the harm done to society by white-collar crime is greater than street crime, most people are not particularly concerned about this form of deviance. Corporate Crime Corporate crime ranges from developing dangerous products to deliberately polluting the environment. DEVIANCE AND SOCIAL DIVERSITY Hate Crimes The term hate crime refers to a criminal act against a person or a person’s property by an offender motivated by racial or other bias. While having a long history in our society, the government has been tracking hate crimes only since 1990. Deviance and Gender Historically, the significance of gender in the study of deviant behavior has been ignored in sociological research. The behavior of males and females has tended to be evaluated using different standards and the process of labeling has been sex-biased. A brief application of the three sociological paradigms is presented. CRIME What is viewed as criminal varies over both time and place. What all crime has in common is that perceived violations bring about response from a formal criminal justice system. Crime contains two elements, the act and the criminal intent. Types of Crime Two major types of crime are recorded by the FBI in its statistical reports known as the crime index. First, crimes against the person, or violent crimes, are defined as crimes against people that involve violence or the threat of violence. Examples are murder, rape, aggravated assault, and robbery. Second, crimes against property, or property crimes, are defined as crimes that involve theft of property belonging to others. Examples are burglary, larceny-theft, auto theft, and arson. A third category, victimless crimes, is defined as violations of law in which there are no readily apparent victims. Examples are gambling, prostitution, and the use of illegal drugs. Criminal Statistics The FBI statistics indicate that crime rates have generally risen since 1960, although recent years rates have shown a downward trend. Figure 6-2 (p. 149) shows rates for types of violent and property crime for the years 1960-1999. THE "STREET" CRIMINAL: A PROFILE Age While only 14 percent of the population is between the ages of 15-24, this age group accounts for roughly 40 percent of all arrests. Gender Statistics indicate that crime is predominantly a male activity. Males are three times more likely than females to be arrested. However, recent evidence suggests the disparity is shrinking. Social Class While research indicates that criminality is more widespread among people of lower social standing, most poor people are not criminals. Expanding the definition of crime to include white-collar crime raises the social position of the "common criminal" significantly. Race and Ethnicity The relationship between race and crime is complex. African Americans, proportionally speaking, are arrested more often for index crimes than whites. Several factors account for this. Prejudice may lead citizens to more readily report African Americans as suspects; race and social class are closely linked to the likelihood of engaging in street crimes; a higher rate of single parenting means African American children are at much greater risk of growing up in poverty; and index crimes fail to take into account white-collar crimes. People of Asian descent have unusually low rates of arrest. Crime in Global Perspective Relative to European societies, the United States has a very high crime rate. Figure 6-3 (p. 151) compares rates of handgun deaths in societies around the world. Several reasons for the relatively high crime rate in the United States have been offered. First, our culture emphases individual economic success. Second, the United States is characterized by extraordinary cultural diversity. Third, the United States has a very high level of economic inequality. Fourth, our society encourages private ownership of guns. Finally, the process of "globalization" is linking the world's societies more closely, allowing crime to more readily cross borders. The illegal drug trade is an example of this last point. THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM The criminal justice system is composed of three components--the police, the courts, and the punishment of convicted offenders. Police The police represent the point of contact between the public and the criminal justice system. They are responsible for maintaining public order by uniformly enforcing the law. Courts The courts determine a person's guilt or innocence. Plea bargaining refers to a legal negotiation in which the prosecutor reduces a charge in exchange for a defendant’s guilty plea. This saves both time and expense, but may undercut the rights of the defendants. Punishment Four justifications for using punishment as part of our criminal justice system are given. These include: Retribution Retribution refers to an act ofmoral vengeance by which society inflicts on the offender suffering comparable to that caused by the offense. In the Seeing Ourselves box (p. 156), National Map 6-2 shows information on capital punishment throughout the United States. We are the only industrial nation in which the federal government imposes the death penalty. However, the states have broadly divergent death penalty laws. Deterrence Deterrence is the use of punishment to discourage criminality. Deterrence emerged as a reform in response to the harsh punishments based on retribution. Rehabilitation Rehabilitation is a program for reforming the offender to prevent subsequent offenses. Reformatories, or houses of correction, exist to provide a controlled environment in which proper behavior is learned. Societal Protection Societal protection is a means by which society renders an offender incapable of further offenses either temporarily through incarceration or permanently by execution. These justifications of punishment are summarized in Table 6-2 (p. 155).