2. characteristics and recent trends in the automotive industry

advertisement

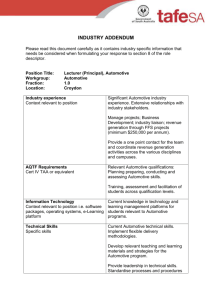

SPECIFIC RESPONSES TO UNIVERSAL PRESSURES IN THE INDUSTRY – COMPARING EUROPEAN AUTOMOTIVE CLUSTERS Marko Jaklic (marko.jaklic@ef.uni-lj.si) Anja Cotic Svetina (anja.cotic.svetina@ef.uni-lj.si) Hugo Zagorsek (hugo.zagorsek@ef.uni-lj.si) University of Ljubljana Faculty of Economics SUMMARY The aim of this paper is to present a comparative analysis of four European automotive clusters: automotive cluster in Saxony (Germany), automotive cluster in Slovenia, automotive cluster in Mlada Boleslav and Liberec (Czech Republic) and automotive cluster in West Midlands (Great Britain). The investigated cases are analysed with respect to the recent changes in the automotive value-chain architecture and other trends taking place in the industry. We discuss in which areas those clusters react universally to those global market changes and present in which areas cluster evolution is more specific, reflecting the national socio-economic context in which cluster is embedded. The automotive industry is going through turbulent changes in terms of changes in the supply-chain architecture, market conditions and technological changes. The response to changing conditions in the global automotive industry can be summarised in few main trends that are emerging in the last decade: consolidation in the industry, gradual transfer of design and development from OEMs to suppliers, search for strategies that will increase or at least keep the level of profitabilityl, technological changes, increased need for knowledge management and innovation, networking and clustering of suppliers in order to supply larger sub-systems or modules. Those are the universal pressures that vehicle manufacturers and their suppliers are facing in the global industry; however their responses can vary considerably. There are several factors like economic history, socio-cultural factors and local embedded ness that are triggering specific cluster evolutionary process. In all four selected clusters, there is a long history of automotive production that is concentrated on more or less limited geographical area. However, recent development of networks among suppliers was influenced by different factors like: economic history, institutional framework, level of labour cost, presence of OEM and its integration in the cluster and policy initiatives taken at local, regional or national level. On the basis of the collected data and case studies for all four clusters we can conclude that despite the universality that is taking place in the industry, the clustering process differs due to context-specific factors. Companies are trying to incorporate in their local environment and use all the resources for obtaining sustainable competitive advantages that will be their basis for competing in the global automotive market. There is a great need for local action as companies are increasingly searching for locally developed competitive advantage and they also expect tailor-made policy action to play an important role in cluster evolution in the future. Keywords: cluster, automotive industry, knowledge Page 1 of 25 SPECIFIČNI ODZIVI GROZDOV NA UNIVERZALNE PRITISKE V AVTOMOBILSKI PANOGI – PRIMERJAVA AVTOMOBILSKIH GROZDOV V EVROPI POVZETEK Glavni namen tega članka je primerjalna analiza štirih evropskih avtomobilskih grozdov: avtomobilski grozd iz Nemčije (Saxony), slovenski avtomobilski grozd, češki avtomobilski grozd (Mlada Boleslav in Liberec) in avtomobilski grozd iz Velike Britanije (West Midlands). Izbrane grozde analiziramo predvsem z vidika sprememb in pritiskov, ki se v zadnjih letih dogajajo v avtomobilski panogi. Zanima nas, na katerih področjih se grozdi odzivajo univerzalno in na katerih področjih so odzivi bolj specifični in odsevajo socio-ekonomski okvir, v katerem grozd deluje. V zadnjem desetletju smo v avtomobilski panogi priča mnogim spremembam, predvsem na področju sprememb v dobaviteljski verigi, poostrenih tržnih razmerah in hitrih tehnoloških spremembah. Odzive na tovrstne pritiske lahko strnemo v nekaj točk: konsolidacija v panogi, postopni prenos R&R funkcij od avtomobilskih proizvajalcev na njihove dobavitelje, iskanje strategij, za ohranjanje dobičkonosnosti, hitre tehnološke spremembe, povečana potreba po upravljanju z znanjem in inovacijami, mreženje in povezovanje avtomobilskih dobaviteljev v grozde z namenom dobavljanja celostnih (modulnih in sistemskih) rešitev. Vsi ti pritiski, ki se dogajajo na globalnem nivoju, so enaki za vse akterje v avtomobilski panogi, vendar pa so njihovi odzivi med seboj precej razlikujejo. Na te razlike vplivajo številni dejavniki, med njimi tudi ekonomski, socio-kulturni in drugi dejavniki, ki izvirajo iz lokalnega okolja, v katerem se grozd nahaja. Vsi štirje grozdi imajo dolgo tradicijo v avtomobilski in sorodnih panogah, vendar pa so na proces grozdenja v teh regijah vplivali še številni drugi dejavniki: ekonomska zgodovina, institucionalno okolje, stroški dela, prisotnost končnega proizvajalca avtomobilov v grozdu, vladni ukrepi (na lokalni, regionalni, nacionalni in EU ravni) in še mnogi drugi. Na podlagi analize zbranih podatkov o štirih grozdih lahko zaključimo, da se proces grozdenja kljub univerzalnim (globalnim) pritiskom v panogi razlikuje. Te razlike so posledica specifičnih dejavnikov v grozdu. Podjetja namreč poskušajo izkoristiti vse prednosti, ki jim jih ponuja lokalno okolje in na ta način pridobiti trajno konkurenčno prednost na globalnem avtomobilskem trgu. To dokazuje, da obstaja velika potreba ukrepih, ki bodo spodbujali razvoj lokalnih posebnosti in konkurenčnih prednosti, ki iz tega izhajajo. Izbrani grozdi poudarjajo pomen prilagojenih ukrepov, ki bodo naslovili specifične potrebe vsakega posameznega grozda in tako dodatno pospešili njegov razvoj. Ključne besede: grozdi, avtomobilska panoga, znanje Page 2 of 25 1. INTRODUCTION The aim of this paper is to present a comparative analysis of four European automotive clusters. The investigated cases will be analysed with respect to the recent changes in the automotive value-chain architecture and other trends taking place in the industry. We will discuss in which areas those clusters react universally to those market changes and present areas where cluster development is more specific, reflecting the local socioeconomic context in which cluster is embedded. In the first section, we will present the main trends in the automotive industry in order to enlighten the global situation that vehicle manufacturers and their suppliers are facing. The automotive industry is going through turbulent changes in terms of changes in the supply-chain architecture, market conditions and technological changes. In the last decade there were many mergers and acquisitions taking place among automotive manufacturers, leading to high consolidation in the industry, where six principal manufacturing groups dominate the market. The companies are increasingly under what is called “productivity squeeze”- on one side there is an innovation pressure, which is coming from the risk of missing new technological advances and losing current market position, more demanding legal requirements in terms of safety and environmental protection and also increased customer’s demands for greater functionality; on the other side there is increasing cost pressure, due to constant price trend in all major vehicle classes as end customers are not willing to pay more for new technologies, and also labour productivity deficits of European producers (compared to US and Japan) (Radke, 2004). Besides automotive manufacturers are facing very difficult market situation in the mature markets of Europe, North America and Japan and are forced to orient toward new emerging markets in Asia (mainly China). Automotive companies try to respond to those pressures by using different strategies; automotive manufacturers try to outsource the activities that bring lower value added and suppliers are taking over increasing responsibility of design and development. This process leads suppliers to form different kinds of cross-functional networks (clusters) of suppliers in different segments (metals, rubber, electronics, plastic, glass textile and services), component producers, toolmakers and R&D institutions. Process of clustering encourages companies to specialise and develop unique knowledge through mutual co-operation and to become integrated in the R&D process in order to supply customised system solutions to final vehicle manufacturers. Formation of clusters in the automotive industry is a logical response to the global trends in the industry and is well known in many countries, like Austria, USA, Great Britain, Czech Republic, Germany, Slovenia and many others. Despite the process of globalisation we believe that automotive suppliers are taking advantage of the local environment in which they operate, trying to identify all possible competitive advantages offered by the local environment. In this sense their response to the universal trends in the industry is very much cluster specific, which will be presented in the second section of the paper. We shortly summarise the four case studies in order the reader to understand further comparisons of clusters. Than we compare the historical process of cluster formation and development and compare the triggering factors that encouraged suppliers to form the cluster. In the third section we identify five factors that seem crucial for specifics in cluster development, namely economic history, institutional framework, level of labour costs and consequently positioning the global value-chain, the Page 3 of 25 level of integration of OEM into the cluster and finally the policy action taken at local, regional or national level to encourage cluster formation. 2. CHARACTERISTICS AND RECENT TRENDS IN THE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY The automotive industry's complex1 product development and manufacturing process makes it one of the most knowledge-intensive industries. The automotive supply chain stretches from various levels of suppliers through to final car producers, so-called OEMs (original equipment manufacturers). Suppliers can be broadly divided into three tiers (Hülsemann, 2004): First-tier suppliers integrate whole systems like brake systems or internal seating for direct supply to OEMs. They provide a high level of R&D and product development as part of the integrated services they supply. Second-tier suppliers provide modules and component parts or support services to the first-tier suppliers for integration into the systems supplied to vehicle manufacturers. Third-tier suppliers supply raw materials for the supply chain or more generic engineering components and services such as mechanical tools, metal castings, rubber and plastics. Figure 1: Types of Companies in the Automotive Industry OEM-Vehicle manufacturers Professional services 1st Tier Suppliers Aftermarket 2nd and 3rd Tier Suppliers Manufacturing services Source: Autoindustry – http://www.autoindustry.co.uk The automotive industry is facing the most difficult market situation in the last five years. Unlike previous downturns, this one seems likely to accelerate broader changes. According to the KPMG’s Auto Executive Survey (KPMG, 2002) the global car industry that emerges in several years could look quite different in terms of industry structure and also in terms of the recent balance of competitors. The companies in the automotive industry are forced to orient from mature markets (Europe, North America and Japan) to emerging and quickly growing markets. Automotive executives see the most potential in Asian markets (especially in China), that are 1 Noting recent technical standards, a modern personal vehicle consists of a few thousand parts supplied by parts suppliers and then assembled through the production chain. Page 4 of 25 expected to become a major source of new sales over the next couple of years. However, it is important to consider that Asian consumers and markets will be different and not the same vehicles as in Europe and North America will be attractive to the growing third-world markets. Consequently, local presence will probably play an important role for succeeding in those markets. Asian producers will be tough competition in those markets as they have already started restructuring their businesses, reinventing their manufacturing processes, redefining their supplier relationships and giving their designers a mandate to create exciting vehicles. We can summarize the response to changing conditions in the global automotive industry in few main trends that are emerging in the last decade: consolidation in the industry, gradual transfer of design and development from OEMs to suppliers, search for strategies that will increase or at least keep the level of profitability, technological changes, increased need for knowledge management and innovation, networking and clustering of suppliers in order to supply larger sub-systems or modules. Consolidation in the industry The global automotive industry saw intensive merger and acquisition activity in the last decade and is today left with six principal manufacturing groups: GM, Ford, Daimler-Chrysler, Toyota, Volkswagen and Renault (KPMG, 2002). The KPMG Survey revealed that in the future cooperative ventures will gain the importance compared to mergers and acquisitions. Automotive supplier sector is also facing the consolidation trend and is expected to remain in a consolidation phase throughout the next decade. According to Pricewaterhouse Coopers, the number of first-tier suppliers is expected to drop from 800 in 2001 to 35 in 2010, while the number of second-tier suppliers will drop from 10,000 to 800 during that period (PWC, 2003). Consolidation of suppliers allows them to improve their negotiating position against OEMs, achieve advantages of increased volume of production and sales and advantage of knowledge exchange. However, both OEM and supplier executives are cautioning against suppliers becoming too large. As one executive said: “It is better to deal with 20 suppliers instead of 200, but those 20 still have to manage the same 200 operations” (KPMG, 2002). Gradual transfer of design and development from OEMs to suppliers We are seeing the gradual transfer of design and supply chain responsibility from manufacturers to their main suppliers, which poses challenges to both manufacturers and their suppliers (Radke, 2004). Between 2000 and 2015 OEMs’ in-house share of added value will drop from 35% to 25%, while on the other hand the suppliers’ share of development (as % of production costs) will on average increase for 70%. OEMs have to maintain adequate expertise in the system although the steps in the value chain that are irrelevant to added value to the customer are being more and more outsourced. This is leading to increased co-operation between OEMs and their suppliers in order to ensure the required technical standards and quality. On the other hand, suppliers have to develop and produce systems that are much more complex than components produced in the past, while simultaneously facing restrictive cost demands by manufacturers. Page 5 of 25 Search for strategies that will increase or at least keep the level of profitability The automotive industry is in its mature stage and as one Tier one executive said: “Profitability is going to be extremely tight for the next four to five years” (KPMG, 2002). Consequently producers are searching for strategies to reduce costs and keep the level of profitability. Among the most important areas for cost savings automotive executives ranked: computer modelling and simulation, assembly innovations, outsourcing and communications (extranet and intranet). OEMs are increasingly outsourcing the activities, especially to markets with lower labour costs. Outsourcing requires strict cost and quality control and OEMs are increasingly asking for transparency from their suppliers in order to meet the required cost structure and quality standards of the final product. As one OEM executive said “In the short term we are going to see more and more collaboration with suppliers bringing the end product to us and we only do the assembling”. However, this trend is not expected to continue to the extreme where OEMs would transform themselves into marketing organisations with little R&D and manufacturing. According to experts’ opinion OEMs would never give up the position of staying at the top of managing costs. Companies in the automotive industry are trying to decrease costs in all areas where possible, but one place where only few expect cost savings is the labour pool. Over the next few years major increases in the cost of pensions, health care and legal services are expected among European and North American automotive executives. But as in other areas Asian companies have an edge as they don’t have the same labour costs or unions to work with, or retirement problems and increasing cost of pensions that automotive firms in Europe and North America are facing with. Technological changes Another trend is related to new technologies used in the automotive production. Among the most important technologies that have tangible benefit to consumers are safety, engine-management system, fuel technology, drive-by-wire electronics, telematics and 42-volt systems. The latter is expected to become critical as vehicles continue to add electronic components, which is one of the industry’s biggest technological trends. The share of electric and electronics is expected to reach 40% by 2015 (compared to 20% in 2002). New technologies used in the automotive production are creating synergies that have impact beyond individual modules and systems and require tight cooperation among different design and production phases. Increased need for knowledge management and innovation The automotive industry is one of the most knowledge intensive industries and throughout the history the knowledge has been created, used and shared over and over again, but it has also been re-created over and over again because the original knowledge was not stored and shared with the whole organisation. Also the results of our research confirm that knowledge is more important for companies in the automotive industry compared with companies operating in other industries. The two recent trends in the industry even increased the need to efficiently manage knowledge. The first is the transfer of increasing design and development responsibility by vehicle manufacturers to their major suppliers, which creates more demand for engineering expertise at the supplier level. The second, which is especially obvious in European and North America is that many employees throughout the industry are retiring, sometimes leaving large gaps in the accumulated knowledge within companies and besides there were many early Page 6 of 25 retirements and lay-offs due to company cost-reduction initiatives (Belzowski et al., 2002). The main challenge the manufacturers are facing is how to capture and retain knowledge of employees, so they do not lose it when they leave and the other is how to maintain adequate expertise in the systems they are now outsourcing to their suppliers. On the other hand suppliers are faced with increased responsibility to design, develop, validate and produce more complex systems. The answer to both challenges probably lies in tight collaboration between manufacturers and suppliers in order to share knowledge and develop innovative products. While competing with Asian manufacturers and suppliers the knowledge is expected to be the next competitive basis (especially for European and North American firms), that differentiates which companies and supply chains win and which lose. The evidence shows that automotive suppliers in investigated clusters are aware of this as they experienced an increase in the number of highly educated staff (holding university degree and diploma) in the last few years. Networking and clustering of suppliers in order to supply larger sub-systems or modules Like OEMs also automotive suppliers have to adapt to the universal trends that are taking place in the global automotive industry and were presented in previous paragraphs. Due to increased complexity of product requirements they need to increase R&D and innovative activity in order to supply sub-modules, modules or even systems for final vehicle production. In order to provide the engineering expertise needed at the supplier level, suppliers in different segments (metals, rubber, electronics, plastic, glass textile and services) are increasing horizontal (cross-functional) linkages and are often forming networks of several material and component producers, toolmakers and R&D institutions. This enables the network to incorporate the whole complexity of automotive industry, which is presented in the figure below and encourages companies to specialise and develop unique knowledge through mutual co-operation and to become integrated in the R&D process in order to supply customised system solutions to final vehicle manufacturers. The clustering process seems to be a natural response to the changes in the values-chain architecture and is well known in many countries (Sölvell, 2003), like Austria where ACStyria (Tödtling, 2001) and three other automotive clusters developed, USA where automotive industry is densely concentrated in Detroit and the surrounding region and in the four cases included in our research project, namely West Midlands in Great Britain, Mlada Boleslav and Liberec districts in Czech Republic, Saxony region in Germany and automotive cluster in Slovenia. Page 7 of 25 Figure 2: Structure of the Automotive Industry Source: Dicken, P. (2003) Global Shift: Reshaping the Global Economic Map in the 21st century. Fourth Edition. London: Sage Publications. 3. THE EVOLUTION OF THE FOUR SELECTED AUTOMOTIVE CLUSTERS In this section we will present the results of the research conducted within 5th Framework Programme under title “Industrial Districts’ Re-Location Processes: Identifying Policies in the Perspective of the European Union Enlargement”2 (Contract no. HPSE-CT2001-00098) (WEID project in continuation). The project involved a detailed investigation of fifteen clusters in seven European clusters. We will focus on four automotive clusters 3 studied within this project, namely automotive clusters in Saxony, Mlada Boleslav and Liberec, West Midlands and Slovenia. The main interest of this paper is how automotive manufacturers and suppliers that operate in clusters respond to the universal pressures of the global automotive industry. Our hypothesis is that despite being exposed to the same pressures their reactions and responses may vary considerably. There are several factors like economic history, socio-cultural factors and local embeddedness that are triggering specific cluster evolutionary process. In four selected clusters, there is a long history of automotive production that is concentrated on more or less limited geographical area. However, recent development of network among suppliers was influenced by different factors that will be shortly discussed in the continuation. The purpose of this section is firstly to examine the main phases and turning points in the history of the investigated four cases and secondly to compare the evolutionary processes that took place in those clusters. 2 More details about the project and the deliverables can be found on the project web page http://www.west-eastid.net/indexintro.htm. 3 In each cluster the primary data was collected through 30 firm's interviews and 5-10 local actors interviews. Page 8 of 25 3.1 THE AUTOMOTIVE CLUSTER IN SAXONY (GERMANY) 4 Before 1990 Saxony was part of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), a region in Germany that was industrialized early and which has a long tradition in automotive manufacturing. This evolution is closely linked to August Horch who developed his first automobile in 1900 and founded the Audi company some years later (http://www.100jahreauto.de). During the crisis in the Saxon automotive industry in 1932, Audi merged with two other companies and the resulting Auto-Union became the second biggest automotive producer in Germany. After WWII and the division of Germany, the company was transferred to Ingolstadt (Bavaria). However, Zwickau and Chemnitz also remained the centres of the automotive industry in the GDR with more than three million Trabands, the famous midget car with its unique duroplast body, being produced in the former AutoUnion manufacturing factories. The region managed to maintain its car-building culture and, after the reunification of Germany, it even increased its international importance. It is surprising that, despite the socialist past of the GDR, suppliers in the region were able to quickly adapt to the new market conditions. This was assisted by many inward FDI in the region that in a way represented a trigger for further industry development. Many OEMs as well as automotive suppliers from former West Germany and abroad have built new factories or taken over and modernized existing ones. Three VW factories that were placed in the region at beginning fell back on its traditional suppliers from West Germany but for example today about 90% of VW’s sources of supply and services come from the region. Since 1993 an important effort was made by the regional Chamber of Commerce which presented regional suppliers and their specific competencies to German and then foreign OEMs. Today, there are more than 700 companies in the automotive and related industries in the region, employing 65,000 workers (Statistisches Landesamt des Freistaates Sachsen, 2004). Several initiatives were launched to enable the whole region to achieve a leading competitive position in the automotive industry and the research showed that initiatives promoting networks were ranked as the most important for the cluster. In 1999 the large network project AMZ-Automotive Suppliers Network Saxony was initiated by the Ministry for Economic Affairs and Labour in order to develop a competence area of automotive suppliers in Saxony. The project’s aim is to achieve product and process innovation by co-operating in networks. In the first three years 87 projects involving 307 participating enterprises were initiated (AMZ, 2004). The projects focus on bundling the present competencies of suppliers into strategic development networks. Network development should enable Saxon suppliers to more intensively integrate into value-adding chains of OEMs and system suppliers and to follow them to their growth markets around the world. The initiative is very broad since all companies supplying the automotive industry have been invited to participate and the network is co-ordinated by RKW Sachsen, a joint organization of employers and unions while all federal state institutions relevant to this industry are represented on the network’s advisory board. Direct public funding covers the network management involving RKW and partly also project managers in networking projects. The main focus of the network lies in initiating, supporting and founding joint R&D and production projects which itself reflects the imperative given by OEMs that asked to be supplied with more complex modules or even systems. 4 Based on the Case Study Report: Automotive ID in Saxony written by Hans Werner Franz. Page 9 of 25 Another important initiative was the creation of an umbrella brand called ‘Autoland Saxony’, which can be used by all of Saxony's automotive industry companies when advertising and marketing their products (http://www.carnet.sachsen.de). This enables the whole region to present itself in Germany and abroad as an attractive automotive industry location. Several networks 5 have also developed within the region bringing together partners from industry, education, science and trade associations in order to enable small suppliers to co-operate and grow into component and system supplier networks. In the case of Saxony automotive cluster we can observe a clustering process supported and founded by the government of Saxony Freestate. The cluster’s main goal is to organize co-operation among competing firms in order to strengthen their joint competence as module or system suppliers. Some part suppliers have already become innovative companies by co-operating with development agencies, which has enhanced their attractiveness to OEMs. 3.2 THE SLOVENIAN AUTOMOTIVE CLUSTER6 Slovenia also has a long tradition in the automotive industry, which started at the end of the 19th century with its first auto mechanical workshops, some of which later changed into producers of component parts for cars. The industry also saw rapid growth in Yugoslavia, when Slovenian producers supplied components for car production in Crvena Zastava. Due to the strong orientation to Yugoslav markets the industry faced a difficult restructuring after the country’s independence and companies simultaneously needed to enter new and more demanding export markets. At that time serving the biggest global players like BMW, VW, Audi, Ford, Magna Steyer, Bosch and others became a great challenge to Slovenian suppliers. Today, more than 80% of car components production in Slovenia, accounting for EUR 950 million, is sold to EU markets, especially Germany and France (Busen, 2004). This proves that Slovenian suppliers are competitive in the global market and according to the sample data Slovene automotive suppliers are investing more in R&D compared to German suppliers, which will help Slovene suppliers to maintain and improve their market position in the future. The trigger for cluster formation came partly from the industry and was later also financially and organisationally supported by the government. The formation started with the Association of Automotive industry at the beginning of nineties, however the process was encouraged by the tender issued by Ministry of Economy in 1999 when Slovenian automotive suppliers applied for governmental support and nine companies and three knowledge-providing institutions were chosen as a pilot cluster project in 2000 (Dermastia, 2002). It was formed as an interest association drawing together members of the mechanical, electrical, electronic, chemical, transport industries as well as R&D institutions, universities and service industries that provide products and services to the automotive industry. The cluster’s goal is to establish a network of companies and institutions and enable its members to become suppliers of more complex parts with higher value added. 5 For example InnoRegio Project IAW 2010 and Autoregio Leipzig. 6 Based on the Case Study: Automotive Cluster of Slovenia written by Dr. Marko Jaklic, Dr. Hugo Zagorsek and Anja Cotic Svetina. Page 10 of 25 The cluster office is taking on the role of a central information point and currently a new information system is being developed in order to improve communication between members and support them with requisite information. Together with the cluster members, the office is very active in cluster promotions at fairs, conferences and visits of/to important customers at home and abroad. There are around 100 companies providing different parts and services for the automotive industry and 49 of them are already members of the formal cluster. As Slovene cluster has quite limited growth potential within the country it is building up co-operation with other domestic and foreign clusters (like the microelectronic cluster in Austria) and industry associations (NAPAK in Russia) (Busen, 2004). Several activities have been undertaken by the office and cluster members in the last four years. However, most important for successful cluster evolution has been the building up of trust among participants, increasing the participation of top managers in cluster activities and the creation of a professional cluster office. It is important for participants to understand the underlying concept of the cluster and be aware that the cluster’s core is its members and the role of the office is mainly to support their activities. These joint activities of cluster members were initially mainly in the area of promotion and education, however five cluster members recently successfully concluded an R&D project to introduce a new product to the market. The growing need for innovation in the industry is encouraging suppliers to establish horizontal and cross-functional linkages and exploit knowledge potential in the cluster, which will probably lead to more joint R&D projects in the future. Compared to the German and Czech case, there were very few FDI in the automotive industry in Slovenia and there is only one OEM (subsidiary of Renault) in the region. The company is not strongly attached to Slovene suppliers as they purchase centrally from Nissan-Renault purchasing panel. Consequently they are not triggering the networking of suppliers, as this was the case in Germany and Czech Republic. 3.3 THE CZECH AUTOMOTIVE CLUSTER7 The Czech automotive cluster is located in the Mlada Boleslav district and Liberec district in the north-east of the country. The local industry is mainly known for its automotive production, which has a long tradition in the region. However, also textile and glass industry are being well developed. The automotive company Laurin&Klement was founded in 1895, first producing bicycles, motorbikes and later cars. In 1925 the company merged with the machinery producer Skoda Pilsen and developed into one of the most significant companies in the country (Skoda Auto, 2004). The production of cars was retained during the communist era (1948-1989). However, with the arrival of new technologies in the West Czech industry began to fall behind and the Skoda company only managed to retain its leading position in Eastern markets. The political changes of 1989 brought about a new economic and market reality. Skoda was then looking for a strong foreign partner to enable it to catch up and invest in the future. Ultimately, in 1991 the Skoda-Volkswagen joint-venture was established. The presence of a foreign-owned automotive producer in the region led to boosting the automotive industry’s 7 Based on the WEID Case Study Report: Mlada Boleslav ID and Case Study: Liberec ID written by Karel Erben, Tambor Market Research. Page 11 of 25 position, which is now the main specialization of the local economy. In addition, related industries like electronics, textiles, plastics and transportation are well developed in the region, providing a strong supplier base for the production of different automotive parts and supportive services. Similarly as in the Slovene case, a culture of co-operation only started to develop after 1991. Before then industrial production was subject to central planning which preferred the autarchy of companies rather than their mutual co-operation or even the creation of networks. In 1990 when foreign trade was liberalized and individual entrepreneurship legalized an environment supportive of co-operation and networking was developed. 21 foreign inventors had entered the region by 2001 and since then local suppliers have been involved in supplier networks with domestic and foreign OEMs (The Czech Automotive Sector, 2004). Like in the German cluster, the inward FDI triggered further industry development. There are 336 firms operating in automotive and related industries in the region, including all three-tier suppliers as well as one very large OEM, namely the Skoda Auto Volkswagen unit that already ranks as Eastern Europe's largest car producer (Czech Statistical Office, 2004). According to local actors, there is little interest in horizontal co-operation between suppliers in the region and relationships among companies are highly formal and driven by rationality, not by any social relationships. At the moment the only two areas expecting positive externalities of co-operation are logistics and education of the labour force. Labour issues are particularly urgent since companies are facing a shortage of local skilled labour, in turn leading to the increased employment of foreigners. There is a private-owned Skoda Auto College that specializes in automotive business, however automotive firms will have to co-operate with the local education system in order to facilitate an expansion of the human skill pool in the future. Despite the great importance of this industry for the region and the whole economy, no specific policy initiative has been identified to systematically support cluster evolution among local suppliers and companies’ representatives ranked policies that promote networking as the least relevant for their region. So far the development of the industry was mainly encouraged by inward FDIs. In our research several policy needs were identified by companies, especially in the area of education and training, development of physical infrastructure and quality development in firms. On the basis of German and Slovene experience, we can conclude that policy initiative launched at regional or national level, could be a helpful trigger for further cluster evolution. 3.4 THE WEST MIDLANDS AUTOMOTIVE CLUSTER8 The UK automotive industry employs around 850.000 people and is worth approximately £40 billion, representing 8% of the global industry size. It contributes 3.4% of gross domestic product and 9% of the UK’s total exports. The automotive components sector, which employs 150.000 people, has and annual turnover of 8 Based on deliverable XXX The West Midlands Automotive ID written by Dr. Odile Janne and Mahtab Farschi. Page 12 of 25 £12 billion and is dominated by a large number of small and medium-sized9 component suppliers (mainly second- and third- tier levels). The West Midlands is one of the smallest regions in England which has a long tradition in the automotive industry. The volume car manufacturing in the region remains uncertain with the two remaining vehicle manufacturers, Peugeot and MG Rover. The key to the future of this region lies in the growth in manufacturing of luxury vehicles through investments by Ford into Land Rover, Jaguar and Aston Martin. Closer relationships between Land Rover, Jaguar and Aston Martin through their common ownership by Ford have led to some recent rationalisation and restructuring of their activities, maximisation of synergies between companies and large investment in production lines improvement (Farschi & Janne, 2003). In terms of research and development the region has long been lagging behind in initiation and implementation of research. However there were several EU initiatives, such as support for the Regional Innovation Strategy, the Research & Development Framework Programmes, extensive funding for research facilities, training and business support and the results of the research show that companies in the UK sample are having the highest R&D investment compared to other automotive clusters and also have on average more employees in R&D activities. 3.5 COMPARISON OF THE HISTORICAL PROCESS OF CLUSTERS’ EVOLUTIONARY PROCESS In four selected clusters there is a long history of automotive production; however different triggering factors influenced the evolution of the cluster. In Saxony and Czech case there was an entrepreneur or a company that started automotive industry in that region, while in the Slovene and West Midlands cases there were no specific incubator firms that would boost cluster formation. In the Saxony case, the leading actor who played a fundamental role for the subsequent district’s formation was August Horch who transferred his company to Zwickau. In 1909 following some quarrel with the company’s management he left the firm and founded across the street what was to become AUDI. In 1932 –during a crisis of the Saxon automobile industry which almost destroyed it– these two firms merged with two other firms and become the Auto-Union. As far as the Saxony automotive case is concerned, the more recent evolution of the cluster owes much to the 1989/1990 German unification. This date is also taken as the cluster’s modern beginnings when the potential of such activities was set free. After that a number of state- or employee-owned firms were privatised and new factories of BMW and Porsche in Leipzig and VW in Mosel/Zwickau and Dresden were open, which enabled the growth of the cluster. The presence of OEMs in the region that are integrated in the local supply base was very important for strengthening the cluster. Additionally, the governmental initiative and funding also contributed to great extent to cluster evolution. Another important event in cluster evolution is the EU enlargement, which poses opportunities for OEMs to outsource to neighbouring Poland and Czech Republic, which both have well developed automotive supply industry. 9 It is estimated that around 7000 automotive component companies operate in the UK, 90% of which are SMEs (AIGT, 2002). These tend to locate geographically close to their customers. Page 13 of 25 Similar course of action happened in the Czech automotive district, where automotive company Laurin & Klement was founded in 1895, which later merged with the machinery producer Skoda Pilsen and became one of the most significant companies in the country. The production of cars was retained until 1991 when SkodaVolkswagen joint-venture was established. The presence of a foreign-owned automotive producer in the region has boosted the development of automotive industry, which is now the main specialisation of the local economy. Despite being foreign owned, Skoda company played an important role in organising a network of competent supplier base, which now represents the core of the cluster. In both cases the most important triggering factor for the evolution of the cluster lies in the socio-political transformation after the fall of the communist system. In both clusters the relocation from other regions or countries was also fostering the growth process. The German cluster has been growing, mainly due to the placement of subsidiaries of large western German OEMs in Saxony. In the Czech case foreign direct investments also played an important role in cluster formation. The process of formation of the West Midlands automotive cluster was different in a way, that there were no specific incubator firms that would trigger the evolutionary process in the cluster and the automotive industry in the region mainly emerged as a result of industrial revolution in the UK. However, there were two important scientists Matthew Boulton and James Watt, who in 1762 founded the Soho metalworks, where they designed and built steam engines. There were also local natural advantages that have been attributed to the success of Birmingham as one of the main centres of industrialisation in the UK: proximity to a source of iron ore, a coal seam and being surrounded by streams empowering the watermills. The district has been established over many decades and there was the concentration of some specialised firms (like motorcycle production) noticeable in the early stages of the ID development. Later on, during 60s-80s the evolution of the cluster has been linked to the aerospace industry (especially during the) and in the more recent decades strongly influenced by the consolidation tendencies in the global automotive industry. There were foreign direct investments firstly done by Japanese firms (e.g. Honda collaboration with Rover), followed by European (e.g. BMW acquisition of Rover, VW acquisition of Rolls Royce, Peugeot) and American automotive firms (e.g. Ford acquisition of Jaguar). The cluster was officially recognised in 2001 and is currently repositioning. The evolution of the Slovene cluster is quite different from the other three. The beginnings of the automotive industry date back to the end of the 19th century; however the formal cluster development started only after Slovene independence in 1991. There is only one OEM operating in Slovenia (subsidiary of French Renault), which is not dependent on the Slovene supplier base and is not integrated into the clustering process. Their purchasing process goes through Nissan-Renault purchasing panel, which has very demanding entering procedure for new suppliers and only few Slovene companies are supplying to Renault (mainly as subcontractors to higher tier suppliers approved by Renault-Nissan purchasing organisation). The trigger for cluster formation in Slovenia came mainly from German and other European OEMs like VW, BMW, Audi, DC, MAN, Bosch, Ford in Germany and others to which Slovene suppliers mainly supply. Their need for more complex products encouraged local suppliers to start collaborating, firstly in terms of promotion and later on also in R&D. Due to the external pressure from OEMs, there was greater need for self-organisation and the group of automotive suppliers started their collaboration within a pilot project of cluster development that was extensively supported by the government. Page 14 of 25 We can conclude that the evolutionary processes of the four clusters are strongly affected and constrained by the recent evolutionary trends that are universal to the global automotive industry, especially by the strategies of consolidation on one hand and outsourcing on the other hand. This is particularly evident in the Slovene, Czech and Saxony clusters which have prevailing characteristics of the satellite type 10 of cluster with a star structure and are typical localised supply systems dependent from the decision taken by very few local and external OEMs. This cluster type is clearly reflecting the specifics of the production-chain involved in the automotive industry, where the large number of local SMEs supplies to first-tier suppliers or even to large multinational OEMs located inside or outside the cluster. The degree of the division of labour is not very extended and the relationship between suppliers and final firms is characterized by sequential interdependence with mainly a oneway flow of goods. The West Midlands cluster is being in many aspects different from other three clusters and is classified as evolutionary cluster. The automotive industry in the region is in its mature phase because, but the suppliers only lately started to form some kind of network or cluster. However, even West Midlands cluster is increasingly dependent on external decision centres considering that the premium manufacturing of strong British brands such as Jaguar, Aston Martin and Land Rover belongs to Ford through its Premier Automotive Group (PAG), which is restructuring its activities and might move sourcing from the UK to other European countries (Sammara, 2004). Clustering in the automotive industry is a logical response to the universal trends that are taking place in the automotive industry on a global scale, however the process of cluster evolution is more or less locally specific. It is the reflection of the socio-economic system in which cluster is evolving. In German, Czech and Slovene case clustering process was strongly influenced by socio-political transformation in the early nineties, while in the British case it was influenced by the industrial restructuring (regeneration) of the region. There are also many other influences that are cluster specific like FDIs to the region, presence of OEMs in the cluster, policy initiatives taken at the local, regional or even national level. Those characteristics, that are also influencing cluster development and especially policy needs of cluster actors, will be presented in the next section. 10 There are several cluster typologies in the literature and, for the purposes of the WEID project we are using the typology of Paniccia, who defined six cluster types: canonical, satellite, evolutionary, science-based, craft-based and area of collocation (Paniccia 2002 and 2004). Page 15 of 25 The main comparative features of the four clusters are presented in the following table. Table 1: The comparative overview of the four automotive clusters Slovenia Formation of the cluster Industry specialization Evolutionary type The most important policy initiative on clustering Area - 1991: establishment of the Association of the Automotive Industry; 2001: creation of a formal cluster Automotive and supportive industries (electronics, plastics, tools, mechanical engineering, textiles and others) Satellite Cluster initiative launched by the Ministry of the Economy 20,300 km2 (Slovenia) Czech Republic (Mlada Boleslav & Liberec) 1989 Germany (Saxony) Great Britain (West Midlands) 1990 1902 (first motorcycles) Automotive and supportive industries (electronics, plastics, tools, mechanical engineering, textiles and others) Satellite Automotive and supportive industries (electronics, plastics, tools, mechanical engineering, textiles and others) Satellite Network Initiative Automotive Suppliers Saxony 2005 founded by Freestate Saxony 18,500 km2 (Freestate of Saxony) Automotive and supportive industries (electronics, plastics, tools, mechanical engineering, textiles and others) Evolutionary 757 (442 parts suppliers, 122 equipment suppliers, 193 service providers) Small and mediumsized firms and some large firms EUR 2,200 3000 11,014 km2 (Central Bohemian region) and more specifically Mlada Boleslav district (1,058 km2) and Liberec district (3163 km2). 336 Number of firms 100 (49 members of the formal cluster association) Distribution of firms by size Mainly medium-sized firms Medium and large firms National average gross monthly salary EUR 1,050 EUR 540 Structure of the cluster Mainly third- and second- tier suppliers, four first-tier suppliers and one OEM (Revoz -Renault) EUR 800 million in 2003 (around 8% of national exports) 13% / 9% / 40% All three tier suppliers, an important is the OEM Skoda Auto Exports Percentage of employees with university degree/ diploma/ qualified employees Data not available 16%/ 15% / 51% Source: WEID Case Study Reports of four automotive clusters Page 16 of 25 All three tier suppliers, domestic and foreign OEMs incl. Volkswagen, BMW, Porsche EUR 13,500 million in 2002 (33% of national exports) 34% / 6% / 50% 13,000km2 9 firms have more than 14% of the workforce £ 460 per week for males £ 270 per week for females All three tier suppliers, domestic and foreign OEMs incl. Volkswagen, BMW, Porsche EUR 7.600 Million or 28,7% of the UK total 30% / 16% / 16% 4. FACTORS INFLUENCING SPECIFIC CLUSTER EVOLUTION AS A RESPONSE TO THE UNIVERSAL PRESSURES IN THE INDUSTRY Through case studies of four automotive clusters we identified factors that in our opinion influence specific cluster evolution as a response to the universal pressures in the automotive industry, namely: 1. economic history11, 2. institutional framework (public, semi-public and private institutions), 3. level of labour cost, 4. presence of the OEM and the level of its integration in the local cluster, 5. policy initiatives that were taken at local, regional or national level. 1. All four investigated regions have a long tradition in the automotive industry, which has an important share of total national exports. Due to the great importance for the national economies involved, automotive industry associations and other support institutions have been developed to promote local industry and to preserve and develop the automotive competence in the particular region. However, in the last decade those institutional frameworks that are influenced by context specific factors (history, socio-cultural framework, economic development of the region) are very much under pressure of universality that is taking place through global trends in the automotive industry (high concentration of OEMs and outsourcing to suppliers). The companies are increasingly under what is called “productivity squeeze”- on one side there is an innovation pressure, which is coming from the risk of missing new technological advances and losing current market position, more demanding legal requirements in terms of safety and environmental protection and also increased customer’s demands for greater functionality; on the other side there is increasing cost pressure, due to constant price trend in all major vehicle classes (after adjustment for inflation) as end customers are not willing to pay more for new technologies, and also labour productivity deficits of European producers (compared to US and Japan) (Radke, 2004). 2. Automotive companies try to respond to those pressures by using all possible competitive advantages offered by the local environment and in this sense their response is very much cluster specific. The characteristic that is common to all four clusters is that they perceive local institutional environment very important. The results of the WEID study show that local public, semi-public and private institutions are an important source of external knowledge for companies in all four clusters. 3. The level of labour costs and consequently also the positioning in the supply chain also have an important influence on how cluster will respond to the pressures in the industry. In Germany, automotive suppliers soon faced the need for co-operation in R&D networks as they needed to focus on more complex products with higher value added due to their high labour costs (the average gross monthly salary in Germany EUR 2,200, in Slovenia EUR 1,050 and in Czech Republic is EUR 540) and also educational structure, as German automotive cluster has the highest proportion of employees with university degree. Suppliers in West Midlands are facing a similar 11 The economic history of all four clusters is more extensively presented in the previous section. Page 17 of 25 situation with almost one third of highly educated employees and high labour costs. Also in Slovenia labour costs are already too high to base the industry’s competitiveness on low prices. As OEMs have started to increasingly outsource in low-cost countries, Slovenian suppliers have faced the challenge of developing and producing more complex and innovative products. This market pressure (mainly from German OEMs) encouraged them to form a network of companies and relevant institution, within which knowledge could be shared, leading to more complex and innovative products. On the other hand Czech suppliers are still able to compete on price, however their educational structure reveals an increasing proportion of highly educated employees and we can also expect that labour costs will soon approach the EU average level and local suppliers will need to organise in R&D networks that will offer system solutions with higher value added. For all four investigated clusters additional cost pressure is constantly coming from less developed countries (mainly Eastern Europe and Asia), forcing European suppliers to orient toward knowledge-intensive activities and outsource operations with lower added value. 4. Another important factor that according to collected evidence influences specific cluster evolution is related to the presence of OEM in the cluster, and even more the level of its integration into the local environment. In the Saxony the process of clustering was to great extent encouraged by several OEMs and system suppliers coming to the region, which increased demand for quality automotive parts and forced local suppliers to organise smaller networks that were able to supply required parts. Similar process happened in Czech Republic, where automotive industry was developed mainly by attracting FDI and the country has since become Europe's leading recipient of automotive projects. Foreign OEMs and system suppliers coming to the region outsourced to Czech part suppliers, giving them opportunity to grow and develop. The organisation of the suppliers base was in this case mainly encouraged by Skoda, which is to great extent integrated into the region and its production system (despite being foreign-owned). Also in the West Midlands cluster there were many FDIs that accelerated automotive industry development. On the other hand, Slovene automotive industry was not very attractive for FDIs and there is only Renault subsidiary operating in the region. The company is weakly linked to the local suppliers base as their purchasing process is centralised and highly dependent. Due to industry pressures and lack of internal triggering factor for clustering (from OEM) Slovene suppliers, which are mainly supplying to German and other European OEMs, had a great need for self organisation which led to the cluster formation in 1999. 5. An important characteristic of automotive clusters is that they expressed a great need for policy action in terms of supporting and encouraging cluster development. Company representatives in four automotive clusters ranked all policy areas more important compared to clusters operating in other industries, which is presented in the following figure. As expected they have the greatest need for policies in the area in education and training, because they have to increasingly base their competitiveness on knowledge-intensive activities. Page 18 of 25 Figure 3: Importance of policies for automotive clusters compared to the average of other investigated clusters (in the present moment) Policies by clusters (present) 3,5 3,0 2,5 2,0 1,5 Other en vi ro nm en ta l er is kc ap ita l St ar tu p ve nt ur VL qu al ity D or k ne tw la bo ur s ui t re cr T& D In fo rm at io nd i ff cu st om ise ds er v R in fra st ru ct ur e Ed uc at io n tra in in g sp ec i fi ca ttr ac ti o n ge ne ra la ttr ac ti o n 1,0 Average Automotive Source: calculations on the basis of WEID database The figure 3 shows that clusters operating in the automotive industry perceive policy initiatives in all areas as relatively more important than clusters operating in other industries. Due to great importance of automotive industry for the regions involved, several policy initiatives were already taken at the local, regional and national level in order to help companies better respond to the changes in the industry. Within the WEID project thirteen policies that can influence cluster evolution were identified: policies attracting new firms to locate in your area, policies attracting your firm to locate in a new area, physical infrastructure development (especially: telecommunication, transport, energy, environmental infrastructures), education and training (individual acquisition of knowledge), research and technological development (collective production and acquisition of knowledge), information diffusion and accessibility for firms (Databases, web-sites, information centres, all of them of general, non-customised nature), policies providing customised services to firms (e.g. environmental services, labelling, participation in exhibitions, logistics, design or new production techniques, market information), policies helping labour recruitment in the area, Page 19 of 25 policies for the establishment of firms’ networks in the area, policy for improving quality development in firms, policies for start-up, incubators of small firms, policies improving availability of venture or risk capital, environmental policies. When we study the four cases we realise that only few of those policies were launched in each cluster and not all policy needs of cluster actors were addressed. Policy initiatives taken were adjusted to the specific cluster context and differ considerably among cases. In Czech, British and German case policy initiatives were launched to attract foreign direct investment that brought OEM(s) to the region. In the Saxony also policy initiatives to encourage joint projects among suppliers and support institutions were launched. Similarly in Slovenia, networking of companies and institutions was encouraged by the governmental co-financing of joint projects. In both cases these initiatives have encouraged a culture of co-operation among companies and institutions and resulted in many successful projects. The effort made by the government and supported by the active participation of the companies has resulted in R&D and production partnerships that have contributed to the good positioning of the cluster. According to the different context in which each cluster is developing, policy needs of cluster actors vary across four clusters, which proves that (despite the universal trends in the industry) automotive clusters need a specific industrial policy at the cluster level in order to base their competitiveness on the factors offered by the local environment. Different perception of which policies are being the most important for each cluster can be seen from the figure 4 below. Page 20 of 25 Figure 4: Perception of the importance of different policy areas for the evolution of the cluster Policies by clusters (present) 4,0 3,5 3,0 2,5 2,0 1,5 NE Bohemia car manufacturing Slovenia car industry AMZ Saxony West Midlands Other en vi ro nm en ta l er is kc ap ita l ve nt ur St ar tu p VL qu al ity D ne tw or k s ui t re cr la bo ur R T& D In fo rm at io nd i ff cu st om ise ds er v in fra st ru ct ur e Ed uc at io n tra in in g sp ec i fi ca ttr ac ti o n ge ne ra la ttr ac ti o n 1,0 Average Automotive Source: calculations on the basis of WEID database In the Czech case cluster actors perceive policies promoting education and training the most important for their cluster, which probably reflects the need to produce more complex products with higher value-added in the future, when labour costs will approach the EU level and it will be no more possible to base the competitiveness on low prices. The same perception was expressed among Slovene companies that were already faced with the need to produce more demanding and innovative products. In both cases great importance is given also to policies promoting R&D, which even further proves the need for transition from “imitators” to “innovators”. German cluster is mainly based on vertical (supplier-buyer) relationships and obviously cluster actors believe more horizontal relationships will be needed in the future as they state that policy action should be oriented toward attracting new firms to the district and encourage them to form networks. Quality level is extremely important in the automotive industry, as many activities are being outsourced and have to meet the required quality standards. Suppliers from the British and Czech cluster perceive quality development as an important area, that should be targeted also through policy action. Those differences in policy needs clearly reflect different contextual characteristics of each cluster like different national framework, policy initiatives taken at local, regional or national level, varying labour cost levels, different positioning in the global automotive value chain, presence of the OEM in the cluster and so on. Page 21 of 25 In the questionnaire company representatives of automotive clusters were also asked to predict importance of several policies in the future. The results show, that the need for policy action in clusters will even increase in the future, which is presented in the following figure 5. Figure 5: Importance of policy initiatives for automotive clusters in the past, present and future Importaince of policies in past, present and future (unweighted average automotive clusters) 4,0 3,5 3,0 2,5 2,0 1,5 Past Present er is kc ap ita en l vi ro nm en ta l st ar tu p ve nt ur R T& In D fo rm at io cu nd st i ff om ise ds er v la bo ur re cr ui t ne tw or ks qu al ity D VL sp ec i fi ca ttr ac ge ti o ne n ra la ttr ac ti o in n fra st ru Ed ct ur uc e at io n tra in in g 1,0 Future Source: calculations on the basis of WEID database We would expect different answers in each cluster regarding the importance of policy action in listed areas in the future, however the responses were relatively homogenous and there were few statistically significant differences between the four clusters. We believe this reflects the universal needs of all companies operating in the automotive industry and raises importance of policy action also in the future. In all selected cases the policy for encouraging educational and training activities is expected to be very important in the future. It was ranked highest among all listed policies in the Slovenian (3.42) and Czech cases (3.67) and it is expected to become the most important policy in the future. Automotive suppliers in selected clusters obviously encounter a growing need for technical expertise in order to supply more complex products. They believe that policies encouraging their acquisition of knowledge should be promoted in the cluster. Another important area is collective production and acquisition of knowledge through joint research and technological development. This area was ranked relatively high in automotive clusters and, in the Slovenian cluster, the policy promoting research and development is even expected to become the most important one in the future. This implies that R&D networks and joint projects should be very much encouraged by local and national governments in the future. The increased need for policy action, which is expected in the future is according to evidence the reflection of the increased market pressure coming from emerging (mainly Asian) markets. The policy initiatives will have to become very cluster specific, developed in the proactive cooperation among cluster actors, policy makers and local institutions in order to use local resources as the basis for competing in the global market. Page 22 of 25 5. CONCLUSION This comparative chapter aims to identify differences and similarities in the four automotive clusters. We analysed the cases with respect to the recent changes in the automotive value-chain architecture and discussed the areas in which the response of local companies (cluster actors) is universal and the areas in which evolution of the cluster is specific to the local context. Both vehicle manufacturers as well as their suppliers are facing several changes in the industry, including the consolidation, which is taking place through mergers and acquisitions, gradual transfer of design and development responsibility from vehicle manufacturers to their suppliers and increased technological complexity of products. Additionally there is a strong pressure coming from the emerging markets, which are on one hand very attractive for outsourcing activities due to much lower labour costs and on the other hand pose a big market opportunity for European and North American vehicle manufacturers. As a response to those challenges automotive suppliers at different segments (metal, rubber, electronics, plastics, glass, textile, services) are forming clusters or other cross-functional networks of companies, R&D and other support institutions. The process of clustering encourages specialisation and creation of knowledge through mutual cooperation, which leads to more complex products and services required by system suppliers and vehicle manufacturers. Despite the universality that is taking place through the trends in the industry presented above, the clustering process differs due to context-specific factors like economic history, socio-cultural environment, local embeddedness, institutional framework, positioning in the global supply chain and others. Companies are trying to incorporate in their local environment and use all the resources for obtaining sustainable competitive advantages that will be their basis for competing in the global automotive market. Automotive industry has a long tradition in all four investigated clusters and is also very important for the national economy (in terms of turnover and exports) in four countries. Consequently, several institutions were developed in selected clusters in order to establish favourable conditions for further industry and cluster development. Also several policy initiatives were launched, including the promotion of FDIs to the region, cofinancing joint projects of companies and research institutions, promoting the cluster at home and abroad and encouraging network creation within the region. Those policy initiatives were cluster-specific, reflecting the varying needs of actors in each cluster. This local response seems to be the right one, as policy needs among clusters are very much different. On the basis of the four investigated automotive case studies and data collected in the field research, we can conclude that there is a great need for local response to global trends taking place in the automotive industry. Despite the globalisation, companies are increasingly searching for locally developed competitive advantages, however they also expect tailor-made policy action to play an important role in cluster evolution in the future. Page 23 of 25 6. REFERENCES 1. AMZ Automobilzuliferer Sachsen, available at http://www.amz-sachsen.de/, 2004 2. Belzowski, B. et al. (2002). Harnessing Knowledge: The Next Challenge to Inter-Firm Cooperation in the North American Auto Industry, The Journal of Automotive Technology and Management 3. Bouton, M. (2004). Presentation of Revoz. Automotive Cluster of Slovenia, 2nd Annual ACS Convention on Developmental Trends in the Automotive Supplier Industry, Ljubljana, 13 May 2004. 4. Busen, D. (2004). Slovenian Supply Industry for the First Incorporation, Opportunities for an Accelerated Development of Complex Products and For Winning Buyers on New Markets. Automotive Cluster of Slovenia, 2nd Annual ACS Convention on Developmental Trends in the Automotive Supplier Industry, Ljubljana, 13 May 2004. 5. Carnet, available at http://www.carnet.sachsen.de 6. Czech Statistical Office, available at http://www.czso.cz, 2004 7. Dermastia, M. (2002). Country Case Study on Local Clusters in Slovenia. Ministry of the Economy, 8 September 2002. 8. Farschi, M. A., Janne, O. E. M. (2003), Industrial Transformation in the West Midlands Automotive Cluster: International Networks and Co-operative Behaviour, presented at the Conference in honour of Prof. S. Brusco: Clusters, Industrial Districts and Firms: The Challenges of Globalisation. Modena, Italy, 12-13 September 2003 9. Hans Werner, F. (2004). Case Study: Saxony Automotive Cluster, Deliverable within WEID project available at http://www.west-east-id.net/indexintro.htm. 10. http://www.100jahreauto.de 11. Hülsemann, K. (2004). Purchasing in the Automotive Industry in the Process of Changes. Automotive Cluster of Slovenia, 2nd Annual ACS Convention on Developmental Trends in the Automotive Supplier Industry, Ljubljana, 13 May 2004. 12. Jaklic, M., Cotic Svetina A., Zagorsek H. (2004.) Case Study: The Automotive Cluster of Slovenia, Deliverable within WEID project available at http://www.west-east-id.net/indexintro.htm. 13. KPMG (2002). Momentum in the Automotive Industry. KPMG, Vol.2, No.1. 14. Odile, J., Farshchi, M. (2004). Case Study: The West Midlands Automotive Cluster, Deliverable within WEID project available at http://www.west-east-id.net/indexintro.htm. 15. Paniccia, I. (2002). Districts: Evolution and Competitiveness in Italian Firms, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA, April 2002. 16. Paniccia, I. (2004). Cutting through the chaos: toward a new typology of industrial districts and clusters. Clusters in Regional Development edited by B. Asheim, P. Cooke, and R. Martin, Routledge, 2004, forthcoming. 17. PWC (2003). What Future for Part Suppliers? Automotive Supply Magazine. Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 20 December 2003, available at http://www.pwc.com/gx/eng/about/ind/auto/automotive_supply_french_english.pdf Page 24 of 25 18. Radke, P. (2004). HAWK 2015 Knowledge Based Changes in the Automotive Value Chain. Automotive Cluster of Slovenia, 2nd Annual ACS Convention on Developmental Trends in the Automotive Supplier Industry, Ljubljana, 13 May 2004. 19. Sammara, A. (2004). Comparative report on: Disticts’ Boundaries, Patterns of Formation and Evolution and Sector/Products of Specialisation, Deliverable within WEID project available at http://www.westeast-id.net/indexintro.htm. 20. Skoda Auto web page, available at http://www.skoda-auto.com/history/company/, 2004 21. Sölvell, Ö.; Lindqvist, G.; Ketels, C. (2003). The Cluster Initiative Greenbook. Ivory Tower AB: 71-79. 22. Statistisches Landesant des Freistaates Sachsen: http://statistik.sachsen.de 23. The Czech Automotive Sector (2004). Czech Invest, Czech Agency for Foreign Investment, 1 March 2004, available at http://www.czechinvest.cz/ci/ci_an.nsf/0/5B17A31219567275C1256B7C0036FC66/$File/automotive% 20EN.pdf 24. Tödtling, F. (2001). Industrial Clusters and Cluster Policies in Austrian Regions, 59–69. 25. 100 Jahre Automobilbau in Wirtschaftsregion http://www.100jahreauto.de, 2004 Page 25 of 25 Chemnitz-Zwickau, available at