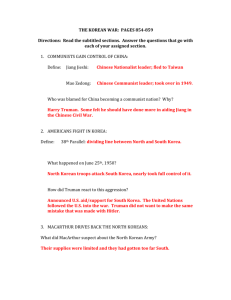

New Russian Evidence on the Korean War Biological Warfare

advertisement