livelihood enterprises for peace and development

advertisement

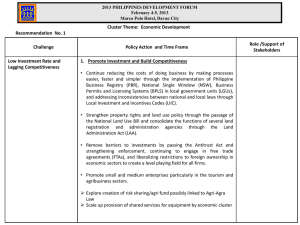

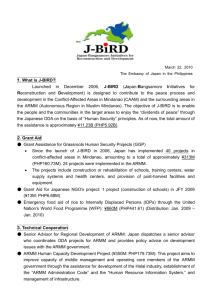

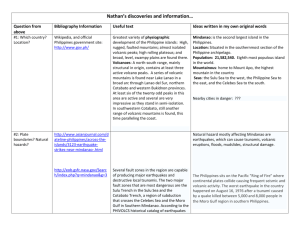

RURAL ENTERPRISES FOR POVERTY REDUCTION AND HUMAN SECURITY By Jerry E. Pacturan I. Historical Background and Context of the PDAP Development Work in Mindanao The Mindanao Colonial Context Mindanao was once called the land of promise due to its vast agricultural lands, rich natural resources and the vibrant economy that was established resulting from the island’s strategic trading links mainly with China as early as 982 A.D. prior to the coming of Islam in the late 14th century. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Sulu, Cotabato in Southcentral Mindanao and Butuan/Caraga, at the northeastern portion, were the flourishing trading centers in Mindanao linked with Europe and China1. In the face of the determined efforts of Spain for three hundred years, from the middle of the 15th century up to the latter part of the 18th century to colonize the entire Philippines, most portions of Southern and Central Mindanao remained free, governed by the Sultanate system (i.e., the Sultanate of Sulu, the Sultanate of Maguindanao and other smaller sultanates). It was this freedom from the Spanish colonizers that up to this day, the Muslims assert was a historical fact that proved they were never part of the struggle against Spain, hence not part of the Philippine nation when the Filipino revolutionary leaders, mostly from Luzon and Visayas, led and almost won the Philippine Revolution against Spain in the late 1800s. The Americans who came at the turn of the 19th century as a result of the Spanish-American War in 1898 and “liberated” the Philippines from Spain in a mock battle in Manila Bay, pursued the same pacification campaign to subjugate the entire country including the Muslim governed areas in Mindanao. The Americans utilized a divide and rule strategy against the Muslims. They entered into an agreement with the Moro leaders through the Bates-Kiram Treaty of 18992 while at the same time fought a cruel war against them. The U.S. gained military victories but has never been totally successful in transforming the socio-cultural and political landscape of the Muslim communities. “The struggle has been costly. From 1903 until 1939, the U.S. initiated ‘land-grabbing laws’ that Sources: Regional Economic Zone Authority/REZA: The Economic Growth Booster, by DTI-ARMM Regional Secretary Ishak V. Mastura; Unpublished Historical Accounts of Mindanao by Greg Hontiveros, Butuan City; Philippine History & Government by Gregorio F. Zaide and Sonia M. Zaide, 5th Edition. 2 Installation of a separate U.S. military administration for the Moro lands and signature of the so-called Bates-Kiram Treaty that provided for a regime of indirect rule, the Americans being only concerned with the maintenance of order and peace. The treaty didn't however prevent frictions and soon revolts broke out. They would last until 1905 in Mindanao and until 1913 in Sulu. (Source: http://www.geocities.com /CapitolHill/Rotunda/2209/Moro.html) 1 Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 1 systematically took away land from the indigenous inhabitants. During this time it is estimated that from 15,000-20,000 Muslims were killed. Despite these losses, Moro and Lumad 3 resistance against colonial rule continued”4. To further counter this resistance, in 1912 the Americans brought to Mindanao large numbers of Filipino Christians from Luzon and Visayas. This continued through the 1950s, completely changing the demographic makeup of the island. In 1918, Moro and Lumads combined made up approximately 75 percent of the total population in Cotabato Province. By 1970, they made up only about 34.5% while Christians made up 62.2 percent.5 Alongside the massive migration of Christians was the entry of American firms that capitalized on the region's economic potential. Between 1900 to 1920, about 46 US firms were established in Zamboanga and Sulu. Agricultural colonies were also said to have been established in Cotabato, Davao, Lanao and Agusan by 1930. 6 The Philippine Government, which was given autonomy by the U.S. in 1935 under the Philippine Commonwealth and full independence in 1946, continue to uphold, up to this day, its sovereign authority in this part of the archipelago, a legacy which most of the Muslim population took with contempt arguing that their “Bangsamoro territory” have been illegally annexed by the Americans as part of the Philippine state in the Treaty of Paris of 1898 7. The communist insurgency in Central Luzon set off by the Hukbong Magpapalaya ng Bayan (HMB) in the 1950s, led the Philippine government to offer an amnesty program for its members by sending the HMB members and their sympathizers to Mindanao and granted them the privilege to own and cultivate agricultural lands. Consequently the influx of more migrants, mostly Christians, from other provinces in Luzon and Visayas followed suit. At around this time the over-all relations among the Mulsims, Christians and Lumads were generally commendable, despite the centuries-old derision by the Muslims against the various invaders, foreign and local, of their homeland. In the early 1970s para-military groups (some attached to Christian politicians, some with Muslim politicians and others with the loggers) proliferated. At this time, land conflicts between Muslims and Christians escalated triggering into armed clashes. The military (then the Philippine Constabulary) took control of many towns and pave the way for the involvement of a para-military group called ILAGA8. The group was responsible for attacking a mosque killing scores of civilians, and driving out Muslims from their communities.9 This event produced a chain reaction in various parts of Mindanao triggering more violent retaliation from both sides. Since then the conflict between Muslims and Christians have been at the center stage of the socio-cultural and politico-economic dynamics in Mindanao. Lumad – the local terms used for the indigenous peoples (IPs) in Mindanao. The Struggle in Mindanao, Documentation for Action Groups in Asia, September 2001. (Source: www.daga.org/dd/d2001/d109ph.pdf) 5 Same with no. 4 above. 6 Source: Dr. Samuel K. Tan of the UP Center for Integrative and Development Studies (UP-CIDS). 7 On April 25, 1898 the United States declared war on Spain following the sinking of the Battleship Maine in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898. As a result Spain lost its control over the remains of its overseas empire -- Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippine islands, Guam, and other islands. 8 ILAGA stands for “Ilongo Land Grabbers Association”. The Ilongos is a Visayan ethnic group originating from the islands of Panay and Negros. The Ilongos is one of the dominant non-Mindanao ethnic groups which migrated to South and North Cotabato. 9 “Overview of the Moro Struggle” by Professor Datu Amilusin A. Jumaani. 3 4 Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 2 The Modernday Muslim Rebellion Against the Philippine Government The seeds of the Muslim rebellion began in the 1950’s with the creation of secessionist movements initiated by Muslim politicians, Senator Pendatun, a Maguindanao 10, of the MINSUPALA (Mindanao, Sulu & Palawan) movement and Congressman Lucman, a Maranao, of the Mindanao Independent Movement (MIM). In the early 1970s, a revolutionary Muslim movement whose following was across the broad socioeconomic classes of the Muslim population was established in Mindanao led by then University of the Philippines (UP) Professor Nur Misuari11. Both the MINSUPALA and MIM joined this new movement. This became as the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) which waged a secessionist war against the Philippine government under the administration of the late President Ferdinand E. Marcos who was elected in 1965. President Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972 and presided an authoritarian regime for almost 14 years. In 1976, President Marcos concluded an agreement with the MNLF in Tripoli, Libya with the facilitation of the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC), granting autonomy in 14 provinces, together with its component cities, in Southern Philippines, including the predominantly Christian provinces of North and South Cotabato. This agreement was never implemented prompting the MNLF to continue its struggle for secession against the Philippine government. Table 1 - Autonomy Areas in the 1976 Tripoli Agreement List of autonomy areas identified in the Tripoli Agreement of 1976 1. Basilan 8. Lanao del Norte 2. Sulu 9. Lanao del Sur 3. Tawitawi 10. Davao del Sur 4. Zamboanga del Sur 11. South Cotabato 5. Zamboanga del Norte 12. Palawan 6. North Cotabato 13. Sultan Kudarat 7. Maguindanao All the cities and villages in the above mentioned areas In 1978, a breakaway faction of the MNLF led by its Vice-Chair Ustadz Hashim Salamat12 asserted itself as the “New MNLF Leadership” primarily due to differences in positions vis-à-vis the Tripoli Agreement. From this faction, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) was formally organized in 1982 and eventually separated from the MNLF 13. The MILF established itself in Central Mindanao with mostly Maguindanaoan following, its forces scattered in the hinterlands of Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur and North Cotabato. Aside from the conflicting positions of the Misuari and the Salamat factions on the Tripoli agreement, the MILF separated with the MNLF owing to ideological and leadership differences, the former being more Islamic in character while the latter being secular in its outlook. In Southern Philippines, there are at least 13 known Muslim ethno-linguistic groups, three of which are dominant in terms of population and political prominence - the Maguindanaos situated in the south-central Mindanao area, the Maranaos in the central-western area and the Tausogs of Sulu. 11 Nur Misuari comes from the Muslim Tausug ethnic group. While a student in UP, Nur Misuari was a member of the Kabataang Makabayan (KM), the youth faction of the National Democrats. His prominent contemporary while teaching in UP was Jose Ma. Sison, founder and former Chairman of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). 12 Salamat, a Maguindanao himself, was the chair of the MILF until his demise in July 2003. He was succeeded by another Maguindanao, Ibrahim Murad. The MILF and the Philippine government resumed the peace negotiation in August 2003 under the facilitation of the Malaysian Government and the backing of the U.S. Government. 13 From an interview with a former chair of the MILF Peace Panel of 2000 which negotiated with the Government of the Philippines. 10 Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 3 The war between the MNLF and the Philippine government was very costly both in terms of lives and economic destruction. Data from the AFP showed that from 1970 to 1996, more than 100,000 persons (i.e., soldiers, rebels and civilians) have been killed in this conflict and P73 billion was spent in the 26year period, or an average of 40 per cent of the AFP’s annual budget. 14 The Peace Agreement of 1996 and Changes in Leadership in ARMM Upon the assumption of then President Corazon C. Aquino, after the fall of the Marcos Dictatorship through the People Power Revolution of 1986, peace negotiations were initiated with the MNLF which finally culminated in the Peace Agreement of 1996 between the Philippine government under the administration of President Fidel V. Ramos and the MNLF under the chairmanship of Nur Misuari. In September 1996, Nur Misuari was elected regional governor of ARMM (Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao). This Peace Agreement led to the amendment and the restructuring of the ARMM 15 through the passing of the Republic Act 9054 in February 2001. At the ensuing referendum mandated by RA 9054, the ARMM region is now composed of the provinces of Basilan, Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, Sulu, Tawitawi and the City of Marawi, while the province of North Cotabato and the city of Cotabato 16 chose to be under Region 1217. In April 2001, ARMM Governor and concurrent MNLF Chair Nur Misuari was ousted as Chair of the MNLF by the other MNLF top-ranking leaders identified as the “Committee of 15”. In the ARMM election of November 2001, Dr. Parouk Hussin, one of the leaders of the Committee of 15, was elected as regional governor of ARMM18. In 2002, Misuari’s loyal forces hold-out and hostage hundreds of civilians and fought-out the AFP in a military camp in Zamboanga City. As a consequence, he fled to Malaysia but was later on deported by the Malaysian government back to the Philippines. He has been incarcerated since then in a government jail in Laguna, Luzon. While the Peace Agreement still holds and is being respected by the MNLF, much needs to be done to complete the devolution process. As claimed by its leaders, out of the 60 executive orders that should have been issued by the President of the Philippines as part of the devolution process, only a handful have been put out to date19. Despite the devolution being incomplete, the peace agreement paved the way for the implementation of donor-initiated development projects in Mindanao by different donor agencies. With the Philippine government operating in deficit hence unable to finance the rehabilitation and development of Mindanao, the donor community has somehow filled-in the gap of providing the much needed resources to rehabilitate, reconstruct and develop the region. Poverty and Underdevelopment in Mindanao and the ARMM Mindanao is the second largest island of the Philippines comprising 94,630 square kilometers and with a population of 18 million or about 23% of the country’s total population of about 80 million. It From the privilege speech delivered in Congress by then Rep. Eduardo Ermita who was formerly the Presidential Adviser for the Peace Process and currently the Executive Secretary of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. 15 The Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) was created on November 6, 1990 by Republic Act 6734 during the administration of then Philippine President Corazon C. Aquino. 16 The center of the regional government of ARMM is situated in Cotabato City, despite not being part of ARMM. This was because in the predecessor RA 6734 of RA 9054, Cotabato was still part of ARMM. 17 The Philippines is composed of 15 regional subdivisions including ARMM and the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) in Northern Luzon. Except for ARMM which is autonomous and has its own regional government structure and Regional Governor, the rest of the 14 regions including CAR doesn’t have a regional government. 18 Governor Hussin’s term will last until mid-2005 afterwhich regional elections will be conducted in ARMM. 19 From an interview with the interim chair of the MNLF, who replaced Chairman Nur Misuari. 14 Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 4 contributes substantial amount to the total GNP of the Philippines. It is blessed with diverse and rich mineral and forestry reserve, as well as abundant agricultural and fishery resources. Decades of highly centralized governance, economic neglect and military pacification campaigns by the Manila central government mainly in response to the Muslim rebellion and communist insurgency in the 1970s and the 1980s have somehow been largely responsible for the state of underdevelopment and poverty in Mindanao which is most pronounced in conflict-affected areas, including the eastern (chiefly Surigao and Agusan provinces) and western regions of the island (Lanao and Zamboanga provinces). It is this poignant state of underdevelopment and poverty that breeds conflict, political instability and unpeace. Indeed, poverty and conflict are twin evils. The poverty situation and underdevelopment in conflict affected-areas in ARMM and other provinces in Mindanao is quite disturbing as recent figures would show. The World Bank in one of its publications confirmed that the island provinces of ARMM have highest poverty levels in the entire country. Even non-ARMM provinces has distressing figures as well. The succeeding table illustrates the poverty statistics in selected Mindanao provinces. Table 2 - Population, Poverty20 Incidence and Depth (1997, 2000) Population Poverty Incidence (Census 2000) 1997 2000 Philippines Metro Manila Lanao del Sur Maguindanao Sulu Tawi-tawi Basilan North Cotabato Sultan Kudarat Davao del Norte 76,498,735 9,932,560 669,072 801,102 619,668 322,317 332,828 958,643 586,505 743,811 25.1 3.5 40.8 24.0 87.5 52.1 30.2 42.7 21.6 26.2 Poverty Depth21 1997 2000 27.5 5.6 48.1 36.2 92.0 75.3 63.0 34.8 35.3 27.3 6.4 0.6 10.4 4.0 33.1 13.4 5.9 13.4 3.2 6.4 7.2 0.9 9.7 9.2 37.3 25.8 16.7 8.8 5.8 7.1 Source: Social Assessment of Conflict-Affected Areas in Mindanao, A World Bank Publication, March 2003 Poverty line is the level of income below which a household is considered poor because it will then be unable to procure sufficient food and other minimum necessities of life. The poverty measurement methodology used by the Philippine Human Development Report is consistent with that used in the World Bank’s two-volume Philippine Poverty Assessment published in May 2001. 21 Poverty depth measures how far below the poverty line the poor are. It measures the poor’s average income shortfall (expressed in proportion to the poverty line) relative to the non-poor. Thus, the data shows that the average income of the poor in Lanao del Sur is 10 percent below the poverty line. The poor in Sulu have average incomes that are more than the 30 percent short of the poverty line. In other words, the income of the poor in Sulu has to rise by an average of 30 percent in order for them to rise above the poverty line. 20 Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 5 Indicators on health are also not encouraging. ARMM has only 29% of its population having access to potable water supply. The following figure illustrates that among the bottom 5 provinces in the Philippines which has low access to safe drinking water, three of them are from the ARMM namely Tawi-tawi, Lanao del Sur and Sulu. Access to family planning services is also very low among the ARMM provinces. The bottom 5 provinces in the country in terms of low family planning access are all in ARMM comprising – Tawitawi, Lanao del Sur, Sulu, Basilan and Maguindanao. In terms of access to sanitary toilets, Sulu (20.8%) and Tawi-Tawi (11.6%), both from ARMM, reported the least percentage of families with sanitary toilets. Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 6 The state of education is also lamentable. Cohort survival22 rate at elementary education level for School Year 2001-2002 especially in Western (45.51%)and Central Mindanao (56.45%) regions and the ARMM (33.96%) are very low as shown in the following table. Table 3- Cohort Survival Rate is defined as the proportion of enrolles at the beginning grade or year which reach the final grade or year. Philippine Statistical Yearbook 2000. 22 Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 7 With these conditions, the imperative for economic development and provision of basic social and health services is critical and necessary. It is in this context that development projects for residents affected by conflict, which help ensure their food security requirements, improve agricultural productivity and increase livelihood options, hence augmenting household income, becomes very vital. The PDAP program in Southern Philippines is a response towards this development challenge. II. PDAP in Mindanao and Palawan The Philippine Development Assistance Programme, Inc. (PDAP)23 program on peace and development in the conflict areas of Southern Philippines began in 1997 immediately after the signing of the peace accord between the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) in 1996. The “Program for Peace and Development in the Southern Zone of Peace and Development/SZOPAD Areas (PPDSA)”, a three year program implemented from 1997 to 2000 and funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) through the PhilippinesCanada Development Fund (PCDF), assisted 84 cooperatives and peoples organizations of former MNLF combatants involving more than 4,000 individuals. The program consisted of capacity building through organizing and technical assistance work and provision of capital for livelihood and enterprise. In 2001, PDAP implemented its second program called “Mindanao Program for Peace and Development (PROPEACE)” still with the support of CIDA and PCDF. With a three-year duration, the program has expanded its assistance to other marginal sectors, the indigenous peoples (IPs) and poor Christian settlers. The program has also included an advocacy component in answer to the need to engage development stakeholders, especially government, in policy formulation and programs that affect the peace and development of the region. PDAP’s focus on livelihood and enterprise creation for its programs in Southern Philippines is in recognition of the state of poverty and underdevelopment in the region particularly in the conflictaffected areas. Working in partnership with community-based groups of Muslim, IPs and Christians since 1997, PDAP has already supported about 180 various projects amounting to almost US$ 2 million. These projects range from agricultural/fish/livestock production and agricultural post-harvest facilities for livelihood and food security to enterprise projects on food and handicraft processing, basic commodities merchandising, micro-financing, grains trading (rice and corn) for increasing household/family income. Objective and Components of the PDAP-Propeace Program The Propeace program’s objective is to improve the socio-economic well-being of 4,000 poor Muslims, Indigenous People (IP) and Christian households in conflict affected areas in Mindanao and Palawan. This is intended to be achieved mainly through the provision of financing and technical assistance for livelihood and enterprise projects of the partner peoples organizations. Included in the component interventions of the program is policy advocacy which is directed at the municipal and regional levels in The Philippine Development Assistance Programme (PDAP), Inc. is a non-government organization established in 1986 composed of 6 NGO networks with more than 300 community-based members or affiliates in the Philippines. PDAP works to reduce poverty and inequity in the Philippines. For the last 16 years, PDAP has supported more than 400 community-based projects for the benefit of close to 2 million Filipinos. It has successfully implemented three major development projects amounting to almost US$ 20 million over three phases of NGO funding support from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). In Southern Philippines, PDAP is currently implementing a 3-year project called Mindanaw Program for Peace and Development (PROPEACE) and a relief and rehabilitation project in Damulog, Bukidnon and Mapun, Tawitawi. 23 Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 8 order to mobilize and operationalize support services from existing policies and programs on livelihood and enterprise promotion. The policy advocacy for the program is also aimed at influencing LGUs and national government agencies as well as donor agencies in developing and implementing new policies, programs and services that benefit the partner organizations and their communities. The succeeding diagram is the program implementation framework of Propeace. Figure 1. Program Implementation Framework NGO Partners PDAP-ProPeace HH-Level OUTPUTS: •Increased Income •Skills Enhancement •Increased Savings Peoples Organizations & Cooperatives Poor Muslims, IPs, & Christian Settlers Govt. Agencies, LGUs & Donors COMPONENTS: •Organizational Development & Capacity Bldg. •Livelihood & Enterprise Development •Policy Advocacy P E A C E and D E V E L O P M E N T Community-based Approach for Livelihood and Enterprise Projects PDAP, in both PPDSA and PROPEACE programs, has adopted an approach of working directly with community-based peoples organizations (POs) and cooperatives. Selection of communities are done in close collaboration with development stakeholders operating in conflict areas such as local NGOs, federation of POs, MNLF leaders and MNLF-allied organizations, Church-based programs, local government units (LGUs), national line agencies as well as donors whose programs do not include livelihood/enterprise components. Project identification, development and implementation are accomplished in a participatory manner. In all these stages, PDAP works as a facilitator using the communities’ own indigenous knowledge, cultural tradition and practices as well as experiences from other communities and projects which are replicable and locally-appropriate. Financing for livelihood and enterprise projects are made available directly to the participating communities. The fund is treated by the POs as perpetual local revolving capital intended to finance continuously their livelihood and enterprise projects. POs whose projects need technical assistance in institutional development and strengthening, cooperative formation and development, financial and business management (i.e., production and marketing) are supported by engaging NGOs and BDS (business development service) providers whose expertise satisfies the project’s requirements. In some instances, LGUs and national line agencies with programs and expertise on PO formation and strengthening are tapped to provide technical assistance. Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 9 Basic trainings and educational programs including coaching/mentoring activities to strengthen the POs/coops organizational management capacity are implemented on-site involving the membership while specialized trainings using experiential techniques and exposure programs are provided to the key leaders and management of the community-based organizations. Institutional networking and linkages geared towards collaborative undertakings at the community and policy levels are initiated by engaging national government agencies, LGUs, NGOs and donor agencies in joint projects and activities. Using these approaches Propeace, since its implementation in 2001 covering mainland Mindanao, Palawan and Tawi-tawi, has accomplished the following: Livelihood and enterprise projects has reached 90 compared to the original program target of 80 projects. Of the total 90 projects, 22 are managed by all-women POs while 68 are led and managed by males. Projects managed by Muslim POs comprises 44 or 49% of the total projects. Table 4 – Livelihood & Enterprise Projects by Sector Livelihood & Enterprise Projects Participating Sector Male Female Muslims Christians IPs Tri-people24 Total 30 13 22 3 68 14 7 1 -22 Total 44 20 23 3 90 Total Program Target 48 16 16 -80 Total Actual 44 20 23 3 90 In terms of the number of individual participants, Propeace has surpassed its original target by 169% reaching 6,242 participants. Female participation is also significant at 47% based on the actual accomplishment. Table 5 – Sectors by Number of Individual Participants Sectors by Number of Individual Participants Participating Sector Number of Participants Male Female Total Total Program Target Muslims 1,377 1,240 2,617 2,400 Christians 626 894 1,520 800 IPs 968 968 1,608 800 Tri-people 313 184 497 -Total 3,284 2,958 6,242 4,000 Percentage 53% 47% 100% 24 Total Actual 2,617 1,520 1,608 497 6,242 (169%) Women play significant role in various Propeace-supported projects. Most of the all-women managed projects are in micro-lending followed by trading and merchandising, Tri-people POs are those with membership from Muslims, IPs and Christians. Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 10 Table 6 – Collective Projects Managed by Women Collective Projects Managed by All-Women POs Type of projects Women Managed Trading & Merchandising 4 Micro-Lending 14 Agri-Agua Production 1 Livestock and Poultry 1 Post Harvest Facilities -Food Processing & Handicraft Production 2 Total 22 Total No. of Projects 22 29 21 5 5 8 90 Stages of Development of Communities in Conflict Areas In almost seven (7) years of working in Southern Philippines in partnership with the marginalized communities of Muslims, Christians and IPs and various stakeholders on peace and development, PDAP realized that communities in conflict areas in the context of livelihood and enterprise promotion go through several stages of development. These six stages mark a continuum from survival to rehabilitation to development and growth (see figure 2). Conflict Situation. Due to massive displacement of communities in a conflict situation, delivery of relief services such as food and medicines are crucial. During this period the need to call for cessation of hostilities is a critical task to prevent further displacement of communities. The role of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), the press/media and peace advocates forming as a “peace constituency” together with the IDPs (internally displaced peoples) to call for ceasefire from warring forces becomes very important. At this stage where the displaced families are living in various evacuation centers, peace education is an effective strategy that helps to heal the trauma and emotional wounds suffered by the IDPs. Dialogue and therapy sessions are implemented to help reduce cultural and religious resentments and biases among the affected. Post-conflict Preparation. In situations where the war is prolonged and formal declaration of cessation of hostilities has not been reached, IDPs play a lead role by asking warring forces to allow them to return to their communities. The “space for peace” model in Pikit, Cotabato spearheaded by the local communities and external facilitators (e.g., NGOs, donors, government agencies, etc.) is one effective and successful approach towards this end. With the expressed willingness of warring forces to respect the peace declaration of the communities affected, the IDPs can start to prepare for their return and rehabilitation which includes activities such as undergoing psycho-social programs and capacity-building planning, village rehabilitation and restructuring, core shelter construction planning, damage assessment and planning for livelihood including basic services requirements. At this level a multi-stakeholder mobilization involving CSOs, government donor agencies and even the private sector becomes very useful in order to generate the necessary resources to support the planned return of the IDPs. Rehabilitation. With the support of all stakeholders including the warring forces (i.e., government and the rebel forces), the IDPs start to go back and settle in their communities to rebuild their damaged houses and community infrastructure (like the village government office and religious structures such as mosques and chapels), cultivate their lands through food for work programs and help implement labor-based construction of water projects. For communities with POs prior to the war, community organizing activities to revive and re-strengthen the organizations are initiated. Agricultural Productivity and Livelihood. At this stage where the IDPs are back and settled in their villages various type of support are provided to make their agricultural activities more productive Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 11 such as introduction of farming systems and sustainable agriculture (SA) technologies, extension of soft agricultural credit, and provision of water for drinking and irrigation purposes. As additional source for food security and household income, projects like backyard food production techniques, inland fish production and livestock production technologies are made available. During this stage continued provision of basic social services on health, literacy and adult education are necessary. Peace education continues to be an important feature in rebuilding family, community and inter-faith relationships in order to sustain the initial peace gains achieved. Micro-Enterprises. Community-based micro-finance or micro-lending projects are effective interventions in assisting households implement both on-farm and off-farm livelihood activities such as food processing, agricultural trading, merchandising, operation of common service facilities for agri-production and processing, agricultural trading and handicraft. Micro-finance modalities vary depending upon the financing needs of the project and the existing culture and traditions of the community. In some projects implemented by Muslim POs, micro-finance policies comply with certain Islamic principles on financing while others simply follow the usual micro-finance standards. At this stage of development, micro-enterprises are also provided with entrepreneurship and technology training, product improvement assistance, basic business management and marketing skills. Savings and capital build-up schemes are also given emphasis to allow formation of internal capital within the community thereby increasing their collective capacity to finance and invest in their own enterprise projects. Peace education at this stage moves up to a higher level when community leaders are tapped to extend peace education in other communities affected by the conflict to expand the peace constituency and assume leadership roles in government and donor-initiated structures that supports the peace and development efforts. Market-Oriented Enterprises. Food-based and food-related micro-enterprises with value added potential such as fish sausage processing, fruit jelly processing, organic sugar production (“muscovado”), cooking oil production are given assistance in product quality improvement, costing and pricing techniques to enhance their marketability. For these products to reach the shelf in malls and supermarkets various enterprise improvement interventions are provided such as labeling and packaging, promotions and consumer education, participation in trade fairs and product presence in various showrooms established by the government and private sector (i.e., chamber of commerce, industry associations, etc.). Non-food products and enterprises such as handicraft and traditional craft weaving possess strong potential for domestic and export markets. These products are given assistance through product quality and design improvement, buyer linkage, participation in trade fairs and presence in showrooms. Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 12 Figure 2. Stages of Development of Communities in Conflict Areas in the Context of Livelihood & Enterprise Development SURVIVAL REHABILITATION DEVELOPMENT & GROWTH MARKETORIENTED ENTERPRISE MICRO-ENTERPRISE AGRI. PRODUCTIVITY & LIVELIHOOD PROMOT’N REHABILITATION POST-CONFLICT PREPARATION CONFLICT SITUATION 5 4 ENTERPRISEFOCUSED APPROACH 3 2 6 COMMUNITY-BASED APPROACH 1 OFF-SITE APPROACH Main concern beneficiary households of Some major factors needed to reach this level Required development interventions Stages of Organizational Growth Food, medicines & temporary shelter Safety & security --- Media advocacy; call for ceasefire Provision of food and medicines, health clinics Relief funds accessing from CSOs, donors, go’vt, private sector. Obtain safety and security commitment from warring forces Rebuilding of core shelters Land cultivation Re-entry plan for IDPs (shelter & livelihood) Village Rehabilitation and Restructuring Plan Negotiations with warring forces Multi-stakeholder mobilization of resources Psycho-social & capacity bldg. for space for peace Agri- support on food for work program Water & health services Community org’n. Peace education Provision of agricultural inputs Provision of social services to address basic needs Establishment Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 Make land productive to ensure HH food security Reduce production risks & costs Agricultural credit Potable water and irrigation Farming systems & SA technology Livestock prod’n. technology Agricultural credit Social services to address basic needs Continuing peace education Regularization Earn additional income Ensure off-season livelihood Seek stable employment Availability & diversity of on-site raw materials Organizational capacity for enterprise Capital formation Enterprise seed capital Skills training Product improvement Organizational capacity for enterprise Marketing Islamic-compatible financing Peace education Institutionalization Sufficient & stable market demand Marketing Technology Support for certification, licenses, trademark & processing Packaging & promotion Peace education Expansion/Innovation 13 The Partners Capacity Index (PCI) One of the innovative tools that PROPEACE has developed is the Partners Capacity Index (PCI). PCI is a PDAP-PROPEACE initiated performance analysis and measurement tool focused on 3 areas – project implementation, organizational management, enterprise management. It is a self-guided capacity development assessment tool that analyzes and measures the community partners performance and growth utilizing applicable measurement tools in organizational and enterprise management and participatory approaches. Partners projects are assessed and classified into 5 types – exceeding expectation (EE), as planned (AP), minor slippage (MiS), major slippage (MaS), poorly implemented (PI). PCI is also a pro-active tool that identifies the applicable course of action that the community partners and assisting agencies have to undertake in order to improve on performance and mitigate constraints and problems in the projects. The following is the summary result of the partner POs PCI ratings. Table 7 – PCI Result for PROPEACE Projects Project performance Exceeding expectation As Planned Minor Slippage Major Slippage # of projects Muslims SECTORS IPs Christians Women Managed Org’ns. with women champion 2 37 0 17 1 10 1 10 1 9 1 16 32 16 6 10 11 19 12 10 2 0 1 2 Poorly implemented 7 3 3 1 0 1 Total 90 46 22 22 22 39 Below are the key findings of the PCI of the PDAP partners: About 79% (71/90) of Propeace partners have fair to excellent capacity in terms of project implementation. These partners were able to carry out planned activities, utilize PDAP grant and mobilize and utilize local counterpart with rating ranging from minor slippage, as planned and exceeds expectation. About 72% (33/46) for Muslims About 77% (17/22) for Ips About 95% (21/22) for Christians 39 out of 90 project were managed / or championed by women in terms of top management. 37 out of 90 projects or 42% are in the operationalization stage in their organizational development 38 out of 90 projects or 42% are in the growth to expansion stage in terms of enterprise performance 79 out of 90 projects or 88% are satisfactory to outstanding in terms of PCI over-all performance At the level of the partner Peoples Organizations (POs) the PCI has been discussed and presented to them for their validation and identification of appropriate course of action that the partners need to take in order to continue to implement their projects effectively, mitigate and improve on their performance. Thus through the PCI the partner POs has greatly realized and has been able to share in the responsibility of sustaining their projects. Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 14 At the service provider level (donors, NGOs, government, LGUs), the PCI generated great interest when it was presented briefly during the PCDF-sponsored thematic conference on livelihood and enterprises on September 29,2004 in Davao City, where donors such as the ADB, JICA, AUSAID, ILO, CIDA and programs like EU-STARCM, UNIDO-Industrial Development Program, etc. were present. At the PDAP level, the PCI is a valuable investment which it will use as a building block for its future program in Mindanao. The PCI is a very useful experience and a basic tool in developing further a comprehensive program performance analysis and measurement framework and indicator system for livelihood and enterprise projects. Important Features of Livelihood and Enterprise Programs in ConflictAffected Areas As communities go through the six stages of development with the end view of promoting the growth of livelihood and enterprises, five important elements come to fore based on PDAP’s experience. Poverty-Focused Poverty and underdevelopment breeds conflict and political instability. PDAP’s response through livelihood and enterprise creation highlights the importance of providing immediate relief for food security and poverty alleviation. For projects to be relevant and responsive to the needs of the communities, PDAP implements a community-focused approach whereby POs/coops decide for themselves the kind of project that are short-gestating which produce immediate results for the project participants. Projects are also based on the natural resource endowments of the area, the enterprise’s market potential, the skills capacity of the participants and their track record. Social Capital Formation War and conflict destroy the fabric of communities and societies. It erodes trust and confidence in individual and community relationships and destroys structures that support communitarian values and traditions. PDAP’s effort in building the individual competencies of leaders and project participants as well as the organizational capacities of communities in organizational and enterprise management and inter-institutional engagement are geared towards the formation of social capital. Gender-fair and environment-sensitive projects are developed and implemented with the community taking a lead role supported by technical assistance interventions. Multi-Stakeholdership Individuals and communities that go through conflict situations loose practically everything that they have including self-esteem. The problems and needs are wide-ranging and diverse enough for any one development program or organization to respond to. For development programs to be effective in conflict areas, development stakeholders need to collaborate and work together so that projects and activities do not duplicate and meager resources are put to better use. PDAP, with its niche in livelihood and enterprise programs working together with other stakeholders, has shown positive results for communities affected by the conflict. In some instances, the Propeace-supported physical structures built by the PO become temporary shelter of displaced families and the venue for psycho-social therapy sessions of the programs implemented by other NGOs. Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 15 Multi-Cultural and Inter-faith Cultural, tribal and religious biases and resentments born out from long historical animosities heighten during conflict situations. Peace education that recognizes the historical root of conflicts, similarities and divergence in cultures and faiths, the affirmation of strengths and common thread that binds communities together despite conflict – are necessary development interventions in conflict areas. Respect for people’s culture and faith, dialogue and joint actions and finding practical ways to work together are measures that facilitate community development action assisted by outside stakeholders. The use of faith-based and culturally-compatible approaches in micro-finance projects manifests the strengths found in the communities traditions and beliefs and provides an element for project viability and sustainability. Agriculture and Enterprise/Industry Orientation Communities emerging from conflict who have been displaced in their economic activities need to revive their farming and other agriculture related livelihood in order to attain food security and free themselves from dependence in relief and rehabilitation work. While PDAP has supported communities in agriculture productivity improvement projects, it also became necessary to support communities to move beyond agriculture productivity especially when such communities have already attain a secured level of food supply/security, has gain some surplus production and therefore ready to go into value-added micro-enterprise and market-oriented activities. Two schools of thought dominate the concept of enterprise creation – one is the necessary presence of a sound market and strong support institutions which allows people to do business and create enterprises, while the other presupposes that individuals with motivation, capabilities and resources interacting with society will have the capacity to create enterprises. PDAP’s approach in building the capacities of people and communities to manage their own livelihood and enterprises is a manifestation of the latter. While institutions and government policies help transform conflict-affected communities into productive and vibrant societies, in the end the people and the communities (i.e., motivated by a vision, possessing the right values and armed with competencies and skills) determine by themselves the kind of development they want. Propeace-supported projects on food processing and handicraft/weaving which are currently marketed within and outside the communities and whose potential can be further enhanced through enterprise improvement strategies demonstrate this belief and aspiration. Lessons and Challenges for Future Programs The recovery of communities ravaged by conflict is determined by many factors. The strength of institutions (i.e., local government, national agencies, church and religious, educational system, financial, business, etc.), the macro policy framework, the micro-environment obtaining in the communities and the people’s inherent and acquired abilities and resources are all necessary in this regard. Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 16 While PDAP has found a niche in livelihood and enterprise promotion in the conflict areas of Southern Philippines, the need to continuously pursue peace and development work (i.e., particularly in livelihood and enterprise creation) is by no means a finished task. Another peace accord 25 seems to be at sight offering yet another chance for pursuing development under a climate of peace. However, much needs to be done. PDAP believes that for development programs to be effective in pursuing peace, several lessons should be taken into account. These lessons serve as PDAP’s guideposts in pursuing its livelihood and enterprise work in Southern Philippines. Peace and development work is attainable in conflict areas given time, a favorable policy environment and resources that directly address the root of the conflict – poverty and underdevelopment. A multi-stakeholder approach involving the national government, local government units, NGOs, donor agencies and local communities creates a “peace constituency” that can push development work towards the attainment of peace in conflict areas. A multi-cultural, inter-faith and diversified approach in supporting community-based structures geared towards change and transformation at the community level. Peace education as the underlying foundation in re-building relationships and forming community structures that promotes the culture of peace and enhances people’s capacities to withstand conflict brought about by warring forces. The use of Islam-compatible principles and other innovative approaches in finance, livelihood and enterprise promotion work and socio-cultural development that has proven to work in other progressive Muslim communities/societies. Human Security as the Over-arching Framework Poverty reduction remains to be the primary concern in a country like the Philippines, and more especially in Mindanao where conflict arises as a natural consequence of impoverishment, injustices, socio-cultural biases and prejudices. However, while poverty remains to be the principal consideration and the chief “lens” for all development interventions, another important “lens” appear to be useful in responding to the development challenges of Mindanao conflict communities, that is the human security framework. Human security is defined as one that focuses on the strengthening of human-centered efforts from the perspective of protecting the lives, livelihoods, and dignity of individual human beings and realizing the abundant potential inherent in each individual. In contrast to National Security which focuses on state-centered efforts rather than people and their communities, the state and their respective governments need to adopt a new paradigm of security. This is paramount “because the security debate has changed dramatically since the inception of state security advocated in the 17 th century. According to that traditional idea, the state would monopolize the rights and means to protect its citizens. State power and state security would be established and expanded to sustain order and peace. But in the 21st century, both the challenges to security and its protectors have become more In 2000, the government under President Estrada’s administration declared an “all-out war” against the MILF which displaced close to a million individuals. Upon the assumption of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo in 2001, peace negotiations were conducted with the MILF. However, in February 2003 extensive armed clashes occurred between the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the MILF which displaced more than 400,000 individuals. A couple of months after this, peace negotiations resumed with the active facilitation of the Malaysian Government & other OIC-member countries such as Brunei. Since then the ceasefire declared and agreed between the two parties has so far been holding and respective by both parties. 25 Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 17 complex. The state remains the fundamental purveyor of security. Yet it often fails to fulfill its security obligations—and at times has even become a source of threat to its own people. That is why attention must now shift from the security of the state to the security of the people.”26 In the context of conflict-affected countries such as the Philippines, and especially in Mindanao where the conflict is manifest, human security as a development framework finds enormous relevance. Specifically this means that development interventions should gear up towards the following: Protecting people or the internally displaced peoples (IDPs) caught in violent conflicts Innocent civilians, women, elderly and children are almost always the unfortunate victims of conflicts resulting from armed clashes between rebel forces and the state military forces. Government has the moral and the constitutional responsibility to see to it that people affected by conflict are protected and taken cared of either in evacuation centers or right in their own communities. Government has the primordial responsibility to use the state resources and apparatus to provide relief and security to IDPs in the same manner that it uses the state resources for war. CSOs, donor agencies as well as the private sector need also to provide complementary assistance to augment scarce government resources. Providing minimum living standards (work-based security; securing livelihoods; access to land, credit, training) As soon as the IDPs are settled in their communities, government and other sectors need to provide rehabilitation activities and consequential development-oriented projects geared towards securing the food security and livelihood requirements of the affected sectors. Landrelated issues which are often a cause of conflict need to be responded and resolved utilizing community-based and culturally-appropriate approaches. State or government-mandated conflict resolution approaches and the legal justice system need to be augmented or attuned with community-based approaches. Training programs have to be directed towards social capital formation and strengthening of communities’ institutional capacity to engage other sectors. Financing for agriculture and enterprise activities need to be adapted to locallyappropriate or culturally-sensitive approaches such as those espoused in Islamic-compatible financing systems. Access to social services such as health and education Health and basic education are critical concerns for communities affected by conflict. Health programs that utilizes modern and alternative traditional systems have to be deployed for the benefit of the marginal sectors. Educational systems in indigenous forms and those that are under the Muslim Madrasah system will have to be effectively utilized to complement modern educational approaches. Formal and non-formal peace education will also have to be directed both at the formal educational system and at the community-level. The latter is most important in the formal educational system where both teachers and students/pupils need to be re-educated or re-oriented on peace education. Articulating common goals, while developing multiple identities (inter-religious dialogue; culture of peace) In Mindanao where different tribal identities abound and various religious persuasions exist (between and among Christians and Muslims), development efforts should recognize the role 26 United Nations-Commission on Human Security Report, 2003. Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 18 and importance of traditional and faith-based (or inter-faith) approaches as a bridge for people to come together towards one common identity as a people. Dialogue within the same religious persuasion (i.e., within and among Christian sects, and even within and among different Islamized tribal groups) and between faiths (i.e., between Muslims and Christians) should be pursued towards a deeper understanding of each other’s faith and beliefs leading towards religious tolerance and formation/acceptance of communitarian values that are universally acceptable embracing all forms of cultural, tribal and faith systems. Empowering communities for good governance (engaged/active citizenship) Effective governance is best addressed both from the perspective of formal governance institutions and the communities/sectors being governed. Governance institutions in conflict communities are oftentimes weak and deeply vulnerable to pressures from the ruling power or dominant sectors (i.e., economic elite, traditional leaders, corrupt government officials and even revolutionary or rebel groups who are yet to settle with the government). Strengthening of these institutions through capacity building and institutional development activities is a must such that they become accountable and responsive to the communities/sectors they are supposed to govern and serve. Communities on the other hand need to engage actively in an organized manner these formal governance institutions utilizing existing windows of opportunity for participation and engagement. In the context of the Philippines and Mindanao, the existing Local Government Code (despite its existing limitations) offers opportunities for communities and organized sectors to participate actively and engage government in providing public goods and services (for the poor and the marginal sectors) necessary for poverty reduction and the promotion of human security. Forming alliances among civil society groups including churches, government and local communities A broad constituency of sectors and institutions that are committed to peace and development is a critical foundation for sustained engagement with all the key stakeholders especially the warring factions (i.e., rebel groups and government/military). Peace is possible and sustainable when the people themselves affected by conflict are united in a common front to fight the root causes of the conflict. The communities themselves taking the initiative of engaging other allied sectors brings forth a “peace constituency” that can effectively push and eventually diminish any form of unpeace or anti-peace efforts from outside. While this is a struggle that cannot be achieved overnight, it is important that the people themselves in tandem with other sectors take the cudgel for peace. Finally, set against the challenges of poverty reduction and human security, PDAP commits to pursue its work on livelihood and enterprise promotion. The last seven years of PDAP work in Mindanao and Palawan has shown that indeed peace is possible and sustainable in the communities where it operated upon. And while PDAP may have played a pivotal role in these communities, ultimately the Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 19 long term sustainability of these efforts will be pursued and determined by the communities themselves as they resolutely uphold their efforts, as well as by the other sectors and institutions (e.g., national and local governments, private sector, donor agencies, financing institutions, educational institutions, NGOs, etc.) operating in the wider macro environment where the bigger challenges lie. Rural Enterprises for Poverty Reduction & Human Security, Jerry E. Pacturan, 7 December 2004 20