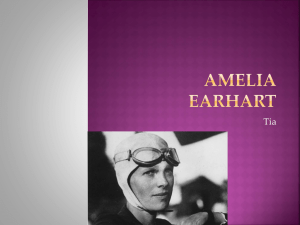

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Amelia (Complete), by Henry Fielding

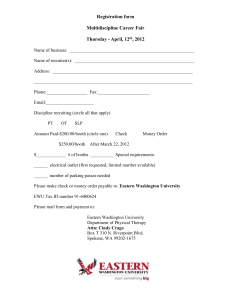

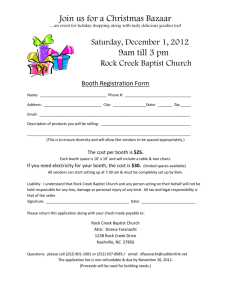

advertisement