Constitution Wk1

advertisement

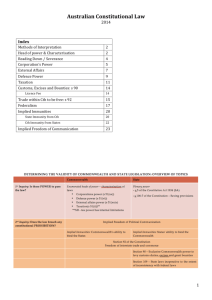

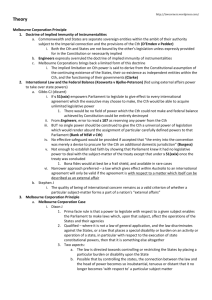

Week 1 CONSTITUTIONAL LAW INTRODUCTION TO THE CTH CONSTITUTION The Nature of the Federal System: The federal system consists of national authority and regional authority which are established as independent governmental units using their own spheres of law making powers. Three Elements: 1. The existence in a geographical area of several governmental units – one having competence over the whole area (national) and the others over the defined parts of it. They share the Queen and the power to govern. 2. A relation between the governing unit, but that each have a reasonable degree of autonomy within their prescribed competence. 3. An inability of any one unit to destroy at will the autonomy of the others. A written constitution defines the limits of the respective governments. Most federal systems have a constitutional court in order to make interpretations as to the meaning of the text and to determine the constitutionality of legislation or executive action - High Court. Federation: What factors prompted the Australian colonies to federate? Commercial and economic interest. The Australian colonists had a common origin in culture, but had separate political development and were at different stages of economic and social development. Need for a common defence effort – concerned about activities of European, Pacific and Asian powers and the possibility of Asian influence in the future. Development of an Australian consciousness/nationalism – united continent. Founders – delegates to the constitutional conventions: All states voted for the constitution and so the draft was sent to the Imperial parliament for enactment. The founders of the constitution were colonial politicians who were generally conservative men of property and some who were liberal thinking and mildly reformist or radical liberals who may be identified with the now labour party. However there were generally a series of shifting coalitions and alliances which inspired fluid political development because the Australian parliament was still very unsettled. There were also free traders (NSW) and protectionists (Vic). There was a division between those who wanted a strong national identity and those who identified with the UK and between smaller colonies and larger colonies. Scheme of the Constitution: The constitution recognises the existence of the Australian colonies. It establishes national governmental entities and outlines the powers and functions of those entities. Attempts to regulate the relations between the national and state authorities. Establishes free trade between the states and a common custom tariff – establishing an Australian common market. Has some guarantees of rights. The distribution of Legislative power: Specific express grants of power are given to the Cth parliament and the general residual power remains with the states. The source of Cth law making powers: Derived from the Cth Constitution Many of the specific express grants of power are set out in s51 (39 paragraphs/heads of power). They are also found in s52. Grants of law making power generally specify the statement ‘until the Parliament otherwise provides’. These concern procedural or administrative powers. The Cth Parl also has some implied legislative powers and a corresponding executive power by virtue of the Cth status as a national polity. This is referred to as the inherent nationhood power. This will not be interpreted broadly by the Court. Source of State law making powers: See ss106, s107, 108 of the Cth Constitution. The colonial Parliaments already had general grants of power to make laws for the "peace, welfare" (in two cases, "order") "and good government" of each colony. S 107 provides that the State Parliaments should continue to have all the powers which they had previously except for those that were vested exclusively in the Commonwealth Parliament. However, only a minority of Cth powers are exclusive (some provisions of s51, s52, those withdrawn from the state by way of prohibition – s114, by way of statement in the Constitution – s90). Concurrent powers: There is no gap in Australian legislative power: the Cth and state power constitutes the totality of legislative power for Australia, thus, most powers granted to the Cth parliament are concurrent – available for both Cth and state parliaments to exercise. Most of the grants of power under s51. These sometimes cause constitutional inconsistencies between Cth and state laws – s109 Cth Constitution: state law will be invalid to the extent of the inconsistency. State residuary power: Not effected by Cth grants of power however, it is flexible and should not be thought of as being exclusive to the states. - Interpretation of cth powers by the High Court can expand the operation of Cth power - Cth parliament can exploit its express power to effect state power. - The Cth can use its financial power to induce the states to comply with the Cth. Although it is true that if the Commonwealth cannot legislate within Australia on a matter it must be within the exclusive power of the States, it is a mistake to think that there are whole areas of law, describable in a word or two, which are exclusive to the States. For example, the States have exclusive power to make the ordinary, general laws relating to crimes (which is most of the laws relating to crimes) - but the Commonwealth can make, and has made, laws with respect to crimes in aircraft travelling interstate, crimes involving posts and telegraphs, crimes in the import of goods, and so on. While it is not "wrong" to refer to States' exclusive powers, as long as they are very carefully defined, it is far more appropriate to call them "residuary" powers. R v Phillips CONSTITUTIONALITY OF STATUTES FEDERAL ACTS: 1. Need for a "Head of Power" There is a need to find a head of law making power. Because the Parliament is one of express powers, there must be a source of power to be valid – s51 for most purposes. 2. Scope of Commonwealth Legislative Powers Two Steps: 1. The Crt interprets the meaning of the provision claimed to give the Parliament the power (usually a para of s 51), 2. It decides whether the Act actually is a law with respect to that particular head of power, as correctly interpreted. 3. Characterisation of Acts Is the law characterised within the scope?? The Court recognises that a law may be logically characterised as a law "with respect to" two, or even many, subjects. If the law can be regarded as a law "with respect to" a head, or heads, of Commonwealth power it is valid - even if it can also be regarded as a law with respect to matters outside Commonwealth power. In particular, a law is valid if its legal effect relates to a Commonwealth power, even if its practical effect or evident purpose relates to something quite outside power. The high court has adopted a dual characterisation method: a law will often have more than one character and as long as a Cth law can be characterised so that one of its characters falls within a Cth head of power, it is sufficient even thought it may be characterised as a law relating to something else. Actors and Announcer’s Equity v Fontana Films. If the Cth law can be fairly characterised as a law with respect to a Cth head of power, it doesn’t matter that the power is exercised on extraneous considerations or that the Cth is trying to achieve ends that aren’t within express grants of Cth power: Murphy Orrs v The Cth: - The Cth had made some prohibited export regulations under the Customs Act in reliance on the power in s51(1). These regulations required that permission to export had to be obtained from the Cth Minister and he refused permission to export mineral sands mined from Fraser Island pending the outcome of an environmental impact study on the effects on Fraser Island. - It was argued that this was a non-Cth subject and the Cth law was a law with respect to environmental protection. - This was rejected by the HC and said that this law dealt with the export of goods and was at the heart of overseas trade and commerce and clearly within s51(1). Thus there was no prohibition or limit on the Cth power. - It was enough that the law dealt with overseas trade and commerce and didn’t matter that there was another extraneous consideration. Thus motive or purpose is irrelevant when considering whether Cth law falls within Cth power. Fairfax v Commissioner of Taxation: - The Cth relying on its taxation power (s51(2)), passed a law that provided for taxation, but allowed for an exemption from taxation if investment were made in certain Cth government securities. - It was argued that it was not a law regarding taxation, but one regarding promotion of Cth securities. - This was rejected as motive or purpose was irrelevant. The direct legal effect of the law must be considered, not the practical consequences or motives. The law was one which imposed taxation and also exempted from it. The substance of the law is the obligation which it imposes and the only obligation imposed was to pay income tax. The Courts have taken a broad and liberal approach to interpreting Cth power: Engineer’s case. Other Interpretative Matters (i) Attitude to precedent The HC has never felt itself strictly bound by its own decisions. This applies in Constitutional cases at least as strongly as in other areas. Street v Queensland Bar Association (ii) Fixed vs evolving meaning of words There is a tension in statutory interpretation between giving a word or phrase the meaning which it had when enacted or the meaning which it has now. The Court has vacillated between these approaches in Const. Law: (iii) Relation of grants of power to each other Since the Engineers' case the Court has generally said that no implications limiting the scope of one head of power should be drawn from the presence of another - but express limitations in one grant have in some cases been given effect to limit other powers (eg, the acquisition of property "on just terms" which we will study later). (iv) Use of Convention Debates In the last two years there has been a number of cases in which the Court has considered the Debates at length in order to ascertain the underlying purpose of a provision of the Constitution (v) Citation of American cases In the last few years the Court has been again paying great attention to American comparisons in the drafting and interpretation of the Constitution - although the American precedents are of course only of some persuasive value and are not necessarily applied. You will see examples later in the course. 4. Constitutional prohibitions/limits??: Express and Implied: Express: - Cth power: s80, s116, s99, s114. State power: s114, s115, s117, s90. Cth and State: s92. Implied: - Cth and State power: political free speech. The constitution envisages Cth and state cooperation: s51, however sometimes gives rise to competition and conflict. STATE ACTS: There is no need to look for a grant of power when considering State laws, though there is a need to look for a connection with the "peace, welfare and good government" of the State if the law is to apply extraterritorially. You do not need to check a State law to see if it is supported by a head of power, but you do need to check whether: 1. Prohibition Does it infringe one of the prohibitions in the Commonwealth Constitution which, although expressed generally, tends to apply particularly to the States - ie, ss 92 and 117; 2. s.52 – Is it within an Exclusive Cwth Power Area?? Does it infringe a prohibition applying specifically to the States (ss 114 or 115), or does it relate to a topic which the Commonwealth Constitution reserves as exclusive to the Commonwealth, ie, ss 52 and 90; 3. Inconsistency with Cwth Law S.109 – The Cth law will prevail 4. Manner and Form Is it contrary to some binding "manner and form" provision regulating the relevant State's power to make certain laws; 5. Extra-Territoriality if it purports to apply outside the State, whether the subject matter has a sufficient connection with the State; SOME GENERAL PRINCIPALS OF INTERPRETATION OF CWTH CONSTITUTION 2. Power Over "Incidental" Matters Note also that there are further discussions of this power, specifically in association with the trade and commerce power, in Zines, Ch 4 and Lane, pp 53-56, and of its use in association with judicial power in Lane, pp 251-252, and in connection with the corporations power in Hanks Textbook, pp 365-366. Burton v Honan (1952) 86 CLR 169 Le Mesurier v Connor (1929) 42 CLR 481 Note the following points: (i) That even without para 51(xxxix) each of the express grants of legislative power would include power to legislate on incidental matters - see Le Mesurier, and the quotes from Crespin & Son v Colac Co-operative Farmers Ltd (1916) 21 CLR 205. (ii) The emphasis in Le Mesurier on the fact that the express power relates to matters incidental to the execution of the other powers, ie, to matters which attend or arise in their exercise, and that therefore it extends further than the incidental aspect of the primary powers - but that nevertheless if the Court finds that some incidental measure is justified it will usually rely in the alternative on the primary power and para 51(xxxix) - at least where the primary power is another power of the Parliament itself. (iii) The fact that para 51(xxxix) also includes matters incidental to the execution of the powers of the executive or the judiciary, and, as the texts agree, this gives it its greater significance. Note Lumb's reference to an "internal security power" based on s 61 plus para 51(xxxix), and to the many provisions relating to court structure and procedure which rely on 51(xxxix). (iv) The (obvious) fact that para 51(xxxix) is an ancillary or attendant power, and therefore cannot be relied upon as supporting provisions which are not supported by a primary grant of power - eg, the Pharmaceutical Benefits case (1945) 71 CLR 237. (v) It is hard to formulate any clear rule for distinguishing between the cases where the appeal to an (implied or express) incidental power was accepted (eg, Burton v Honan, Jumbunna) and those where the argument has failed (eg, Le Mesurier and Gazzo) - You should simply know of several examples going each way and accept that each case depends on the judicial impression of the facts. This issue will arise again in the cases studied under later topics - watch out for it in particular in connection with the trade and commerce power, corporations power, industrial disputes power, Parliament's power to appropriate money and the executive's power to spend it. 3. Severance Note the following points: (i) Despite the general words of s 15A, the Court is unwilling to save an Act by severance if that will result in a substantially different Act from that which Parliament seems to have intended, or if the invalid part is such a substantial part of the Act that Parliament could not have intended to enact the rest. (ii) The Court has traditionally been more reluctant to read words of a statute down (ie, to limit their meaning) than to simply sever out some words, sections, or Parts of an Act. In particular, it may refuse to read down if it cannot find "a standard on the face of the Act" to give it some guidance as to what valid operation Parliament would have intended it to save (Pidoto). (iii) However, where the Court can find evidence that Parliament meant some generally expressed words to have a "distributive effect", it may read them down - see Henry's case. [Note that Lane, in both Manual and Digest, calls this "distributive severance" as opposed to "divisible severance" (as in the Airlines case). However, Howard sticks to the terms "reading down" and "severance" respectively.] Recently the Court has gone to remarkable lengths to save Acts from invalidity. In Love v Attorney-General (NSW) (1990) 90 ALR 322; 64 ALJR 175, it saved a State Act regarding warrants for telephone tapping from inconsistency simply by assuming that it was not meant to apply where the Commonwealth Act applied. And see Bourke v State Bank of NSW, under the Banking power, but compare Re Dingjan, under the Corporations power, in Week 5. 4. Techniques for Exploiting Several Powers in One Act Read: Strickland v Rocla Concrete Pipes Ltd R v Australian Industrial Court; Ex parte CLM Holdings Pty Ltd The cases listed above both involve attempts to regulate the widest possible range of trade practices. As to the 1965 Act, see the Concrete Pipes case, and note how the substantive provisions (eg, s 35) referred generally to all persons engaging in a practice, without any attempt to relate the provision to Commonwealth legislative powers, but then everything was qualified by s 7. The majority held that this was invalid, as s 7 could not be read distributively or saved by severing - those who want to try to understand why should look up Barwick CJ's judgment at CLR pp 491-499 or ALJR pp 491-494. Note however that two Justices dissented persuasively. As to the 1974 Act, see CLM Holdings. Note that the Act is drafted principally as an Act with respect to corporations, but that s 6 then in effect creates several alternative Acts by redrafting the substantive provisions. Note the Court's lack of difficulty in understanding the effect of s 6 or in finding it valid. (As an understanding of the Constitutional reach of this Act is vital in commercial practice, we shall study it further in a seminar question.) Note that more recently the Commonwealth Parliament has adopted yet another approach to maximising the scope of its legislation. Acts now are drafted with much use of phrases such as "eligible persons" and "eligible circumstances" and these terms are then defined by reference to all relevant Commonwealth powers - eg, "eligible persons" will include trading or financial corporations, persons in Territories, etc, and "eligible circumstances" will include involvement in interstate or overseas trade or commerce, using posts or telegraphs, doing anything in a Territory, etc. It seems clear that this approach will not create Constitutional Law problems of the Concrete Pipes kind - but people considering the application of the Act will constantly have to remember Constitutional law in order to interpret the definitions. Even more recently the drafters have reverted to an even simpler approach, only a little different from the one in the Trade Practices Act 1965. See the discussion of the Therapeutic Goods Act in Seminar No. 6, Question 2. If this approach is upheld by the High Court (and the Act will surely be challenged before long), the drafting of Commonwealth Acts will become much simpler - at least in this respect.