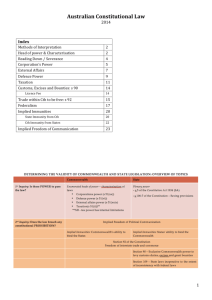

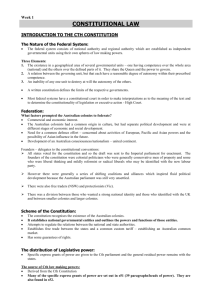

Theory_Melbourne Corp_Constitutional

advertisement

http://lawcorners.wordpress.com/ Theory Melbourne Corporation Principle 1. Doctrine of Implied Immunity of Instrumentalities a. Commonwealth and States are separate sovereign entities within the ambit of their authority subject to the Imperial connection and the provisions of the Cth (D’Emden v Pedder) i. Both the Cth and States are not bound by the other’s legislation unless expressly provided for in the Constitution or necessarily implied b. Engineers expressly overruled the doctrine of implied immunity of instrumentalities c. Melbourne Corporations brings back a limited form of this doctrine i. The implied limitation on Cth power is said to derive from the Constitutional assumption of the continuing existence of the States, their co-existence as independent entities within the Cth, and the functioning of their governments (Clarke) 2. International Law and the Federal Balance (Koowarta v Bjelke-Peterson) (fed using external affairs power to take over state powers) a. Gibbs CJ (dissent) i. If s 51(xxix) empowers Parliament to legislate to give effect to every international agreement which the executive may choose to make, the Cth would be able to acquire unlimited legislative power 1. There would be no field of power which the Cth could not make and federal balance achieved by Constitution could be entirely destroyed ii. From Engineers, error to read s 107 as reserving any power from the Cth iii. BUT no single power should be construed to give the Cth a universal power of legislation which would render absurd the assignment of particular carefully defined powers to that Parliament (Bank of NSW v Cth) iv. No effective safeguard would be provided if accepted that “the entry into the convention was merely a device to procure for the Cth an additional domestic jurisdiction” (Burgess) v. Not enough to establish bad faith by showing that Parliament knew it had no legislative power to deal with the subject-matter of the treaty except that under s 51(xxix) once the treaty was concluded 1. Bona fides would at best be a frail shield, and available in rare cases vi. Narrower approach preferred – a law which gives effect within Australia to an international agreement will only be valid if the agreement is with respect to a matter which itself can be described as an external affair b. Stephen J i. The quality of being of international concern remains as a valid criterion of whether a particular subject-matter forms a part of a nation’s “external affairs” 3. Melbourne Corporation Principle a. Melbourne Corporation Case i. Dixon J 1. Prima facie rule is that a power to legislate with respect to a given subject enables the Parliament to make laws which, upon that subject, affect the operations of the States and their agencies 2. Qualified – where it is not a law of general application, and the law discriminates against the States, or a law that places a special disability or burden on an activity or operation of a state, in particular with respect to the execution of state constitutional powers, then that it is something else altogether 3. Two aspects: a. The law is directed towards controlling or restricting the States by placing a particular burden or disability upon the State b. Possible that by controlling the states, the connection between the law and the head of power becomes so insubstantial, tenuous or distant that it no longer becomes ‘with respect to’ a particular subject matter http://lawcorners.wordpress.com/ b. c. d. e. 4. Even though s 109 puts the Cth in a superior position to the States, it does not mean that State governments are a branch office of the federal parliament. It retains its character as independent entities notwithstanding the Cth superiority 5. As a consequence, unless a given legislative power appears from its content, context or subject matter s to intend, it should not be understood as authorizing the Cth to make a law aimed at the restriction of a State in the exercise of its executive authority 6. Basis of limitation: derived from the federal compact ii. Starke J 1. Beyond the power of either Cth or State to abolish or destroy the other 2. Test: whether Cth is curtailing or interfering in a substantive matter the exercise of the constitutional power by the State iii. Latham CJ and Williams J 1. Basis of limitation: question of characterisation – if a law is direct towards restricting or controlling the states, it does not fall within the HOP (similar to Engineers) iv. Rich J 1. Invalid if Cth action prevents State from continuing to exist or function – 2 instances: a. Where they single out states and impose restrictions upon them b. Law of general application will impose such burdens that it will prevent the states from carrying out its governmental duties Qld Electricity Commission v Cth i. Mason J 1. Discrimination limb: not every law that deprives a State of a right, privilege or benefit that it enjoys will amount to discrimination. Austin v Cth i. One-limb test endorsed – Cth laws will only be invalid if they impair the State’s capacity to function as a polity ii. Discrimination is not enough Clarke i. Hayne J 1. It is for a state to decide how and with what amount its parliamentarians are to be remunerated 2. The law impairs the capacity of a state to choose between these various forms of remuneration 3. The state has no real choice but to adopt a method of providing retirement benefits that will enable parliamentarians to meet the tax liability specifically imposed on them ii. Gummow, Heydon, Kiefel and Bell JJ 1. One limitation – discrimination as an illustration of how it impairs the capacity of the state to function in accordance with the constitutional conception of the Cth and States as constituent entities Workchoices i. Callinan J 1. Amenable to broader ‘federal balance’ argument a. Nothing to suggest that powers of the Cth should be enlarged “so that the Parliament of each State is progressively reduced until it becomes no more than important debating society” b. Court is not permitted to ‘reshape the Constitution’ c. States are ‘substantial and permanent polities’ with full legislative and judicial powers, and must remain so 2. Criticised majority judgment as ‘the reach of the corporations power, as validated by the majority, has the capacity to obliterate powers of the State hitherto unquestioned’ ii. Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Crennan JJ http://lawcorners.wordpress.com/ 1. What was discarded in Engineers was an approach to constitutional construction that started with a view of the place to be accorded to the States formed independently of the text; but did not establish that no implications can be drawn from the Constitution 2. In this case, appeals were made to notions of federal balance – two points made: a. As Dixon J said in Melb Corp, the position of the federal government is necessarily stronger than of the States. The Cth is a government to which enumerated powers have been affirmatively granted. The grant carries all that is proper for its full effectuation. Then supremacy is given to the legislative powers of the Cth b. Dixon J in Melb Corp: framers ‘appear to have conceived the States as bodies politic whose existence and nature are independent of the powers allocated to them 3. Issue for majority: at which point are the powers of the federal Parliament and the State be divided lest the federal balance be disturbed, and how is that point to be identified? f. Summary i. Melbourne Corporation principle provides the States an immunity from Cth laws which would ‘impair the State to function as a constituent entity of the federal structure’ (Clarke) 1. Discrimination is a possible manifestation of this; not a standalone ground of invalidity (Austin) ii. Does not provide any broader guarantee of ‘federal balance’ Constitutional Interpretation 1. Jumbunna Coal a. O’Connor J i. Endorsed approach in McCulloch v Maryland 1. Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional ii. Constitution is broad and general in its terms, intended to apply to the varying conditions which the development of the community iii. Should lean on the plenary interpretation unless there is something in the context or rest of the Constitution to indicate the narrower interpretation will best carry out its object and purpose b. ANA Case i. Interpreted to mean ‘construed with all the generality which the words used admit’ c. Comparison with Engineers i. Both give wide reading of s 51 ii. Far more willing to look at PURPOSE of the Constitutional provision iii. Willing to give s 51 a narrow interpretation if it served underlying purpose d. Pape v Commissioner of Taxation i. Heydon J (dissent) 1. Tried to rein in the approach of broad interpretation 2. Constitutional grants of power should not be given wide meaning where context indicates otherwise. Context includes federal nature of Constitution and history of its enactment Judicial Detention 1. Chu Kheng Lim principle a. Involuntary detention of a citizen may only be ordered by a court, in consequence of a judicial finding of criminal responsibility b. Expanding nature of exceptions has led to questions about whether there is an ‘immunity’ at all (Gaudron J in Kruger) http://lawcorners.wordpress.com/ 2. Kable a. McHugh J i. Invests State courts with federal judicial power ii. Legislation directed to exercise of State jurisdiction – but incompatibility does not depend upon intention; it depends on effect iii. At Federal level, cannot give courts non-judicial function; At State level, it can exercise nonjudicial functions as long as the power is not incompatible with their federal functions b. Dawson J (in dissent): i. Acknowledges that State courts must exist, but Cth must take them as they find them ii. May still invest federal judicial functions, but they are still State courts iii. No incompatibility – no integration of State and Federal systems iv. Suggestion of the idea that the words/existence of Ch III necessitates a denial of State power is viewed as an abuse c. Noted by Kirby J in Baker – a constitutional guard-dog that would bark but once? i. Suggestion that Kable was extreme, legislation would never be invalidated on this basis again (McHugh J in Fardon) ii. Barked again in IFCT; Totani 3. Subsequent Cases a. Fardon i. Gummow J 1. Alternative to Chu Kheng Lim: purpose not to punish, but to protect 2. If a similar scheme would be valid at the federal level, then the same principle can be applied to the State level ii. Kirby J (dissent) 1. Objects to the narrowing of Kable b. Kruger i. Gaudron J 1. Exceptions recognised in Lim are neither clear nor within precise and confined categories 2. Acknowledgement by Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ that the immunity does or may not operate in war time is inconsistent with the notion of a ‘general immunity’ from involuntary detention deriving from Ch III 3. True position: subject to certain restrictions a law authorizing detention in custody, divorced from any breach of the law, is not a law on a topic with respect to which s 51 confers legislative power 4. Because power to authorise detention in custody is not exclusively judicial in character, Ch III is not the source of any such limitation ii. Gummow J 1. A power od detention which is punitive in character and not consequent upon adjudgment of criminal guilt by a court cannot be conferred upon the Executive by a law of the Cth a. If law characterized as punitive in nature, it attracts the operation of Ch III c. Al-Kateb v Godwin i. Hayne J 1. Whether law ‘reasonably capable of being seen as necessary’ for non-punitive purpose may be more appropriate whether the law is a law ‘with respect to’ a particular head of power 2. Relevant power not so confined as is implicit in the reasons in Chu Kheng Lim 3. ‘Constitutional immunity’ difficult to identify with any certainty. It is an assumption which turns upon the connection between such detention and the relevant HOP ii. McHugh J 1. Ch III is always infringed where the detention of a person other than by curial order is authorised by a law of the Cth and imposes punishment http://lawcorners.wordpress.com/ 2. “The justice or wisdom of the course taken by the Parliament is not examinable in this or any other domestic court” because “it is not for the courts… to determine whether the course taken by Parliament is unjust or contrary to basic human rights” iii. Gummow J (dissenting) 1. Refers to McHugh in Chu Kheng Lim – although detention under a law of Parliament is ordinarily charactised as punitive in character, it cannot be so characterized if the purpose of the imprisonment is to achieve some legitimate non-punitive object… but if imprisonment goes beyond what is reasonably necessary to achieve the nonpunitive object, it might be invalid because it infringed Ch III 2. Brennan, Deane, Dawson and McHugh JJ approach in Lim preferred (immunity rather than characterization (Gaudron J)) d. Re Woolley i. McHugh J 1. Goes too far to say that, subject to specified exceptions, detention by the Executive is always penal or punitive and can only be achieved as the result of the exercise of judicial power 2. The object for which the law authorises or requires the detention is an even stronger indication of whether the detention is penal or punitive in nature a. From Callinan J in Al-Kateb – the purpose of the law that authorizes detention is the ‘yardstick’ for determining whether law is punitive in nature 3. Two-step process argued a. Identify a legitimate non-punitive objective to which the law is directed; and b. Whether the law is “reasonably necessary” or “reasonably capable of being seen as necessary” or “appropriate and adapted” to achieve that purpose or objective [considerations of proportionality] 4. New Test: a law that authorises detention will not offend the separation of powers doctrine as long as its purpose is non-punitive (drawn from Al-Kateb – none of the majority applied the preferred ‘reasonably capable of being seen as necessary’ test 5. Infringement of Ch III cannot be saved by asserting that its operation is proportionate to an object that is compatible with Ch III a. Otherwise, can invest in non-judicial tribunals e. Thomas v Mowbray i. Gleeson CJ 1. Not correct to say, as an absolute proposition, that under our system of government, restrains on liberty exist only as an incident of adjudging and punishing criminal guilt ii. Gummow and Crennan JJ 1. Mere fact that a court is required to take into account considerations of policy when exercising its discretion is not enough to make it a non-judicial function a. Where legislation is enacted to effect a policy, inevitably consideration of that policy cannot be excluded form the curial interpretative process 2. Nothing to suggest that the court is to act as a mere instrument of government policy – does not infringe Ch III iii. Kirby J (dissenting) 1. Exercise of judicial power governed by ‘defined or definable, ascertained or ascertainable standard’ (Re Judiciary and Navigation Acts) 2. Invites court to prognosticate about the likely contribution of the order to the prevention of a terrorist attack a. Does not provide a legal standard – executive function only