yrdudtyjdtcy

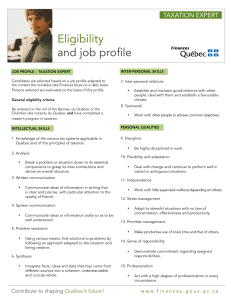

advertisement