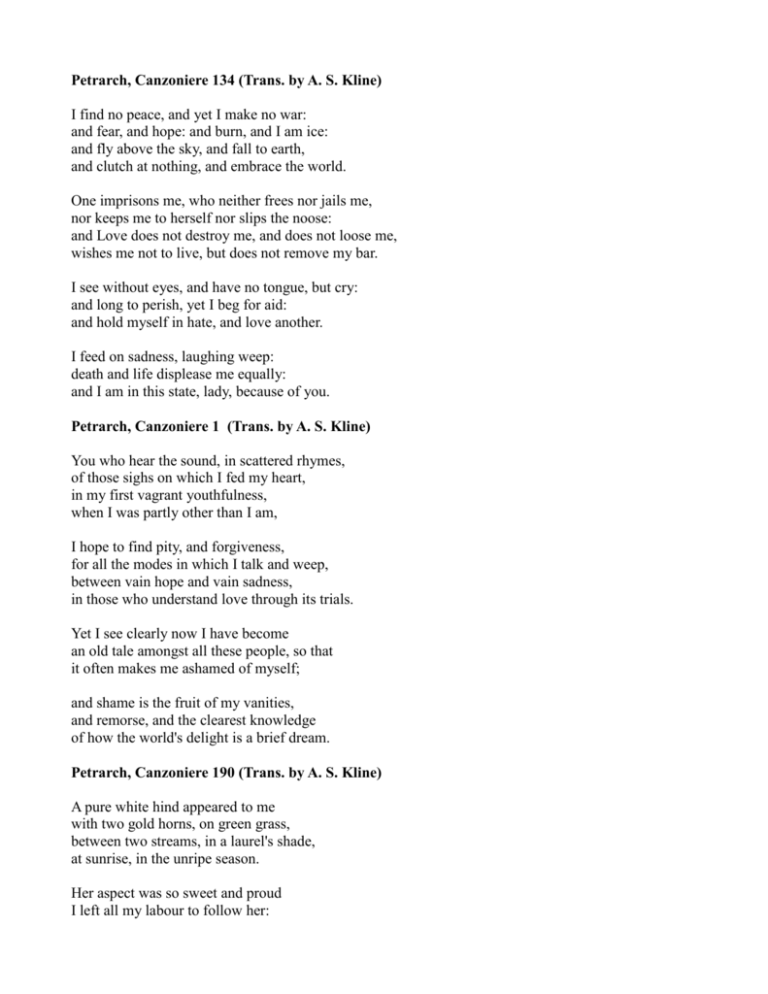

Petrarch, Canzoniere 134 (Trans. by A. S. Kline)

I find no peace, and yet I make no war:

and fear, and hope: and burn, and I am ice:

and fly above the sky, and fall to earth,

and clutch at nothing, and embrace the world.

One imprisons me, who neither frees nor jails me,

nor keeps me to herself nor slips the noose:

and Love does not destroy me, and does not loose me,

wishes me not to live, but does not remove my bar.

I see without eyes, and have no tongue, but cry:

and long to perish, yet I beg for aid:

and hold myself in hate, and love another.

I feed on sadness, laughing weep:

death and life displease me equally:

and I am in this state, lady, because of you.

Petrarch, Canzoniere 1 (Trans. by A. S. Kline)

You who hear the sound, in scattered rhymes,

of those sighs on which I fed my heart,

in my first vagrant youthfulness,

when I was partly other than I am,

I hope to find pity, and forgiveness,

for all the modes in which I talk and weep,

between vain hope and vain sadness,

in those who understand love through its trials.

Yet I see clearly now I have become

an old tale amongst all these people, so that

it often makes me ashamed of myself;

and shame is the fruit of my vanities,

and remorse, and the clearest knowledge

of how the world's delight is a brief dream.

Petrarch, Canzoniere 190 (Trans. by A. S. Kline)

A pure white hind appeared to me

with two gold horns, on green grass,

between two streams, in a laurel's shade,

at sunrise, in the unripe season.

Her aspect was so sweet and proud

I left all my labour to follow her:

as a miser, in search of treasure,

makes his toil lose its bitterness in delight.

'Touch me not,' in diamonds and topaz,

was written round about her lovely neck:

'it pleased my Lord to set me free.'

The sun had already mounted to mid-day,

my eyes were tired with gazing, but not sated,

when I fell into water, and she vanished.

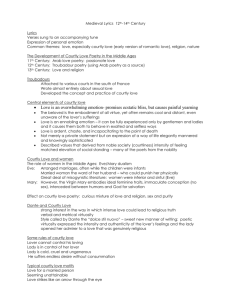

Courtly love, or amour courtois—a Medieval concept guiding the expressions of love and admiration

between members of the nobility, courtly love is somewhere between erotic love and spiritual love. It

features a lord or knight who idolizes his lady and seeks to win her affection by acting chivalrously,

honorably, and nobly. It is a transcendent, elevated form of love, but one informed by sexual desire and

eroticism. In the Medieval world, courtly love was not an expression of love characterizing marriage—

it was about the forms and feelings of elevated emotionalism, rather than the pleasures (or more likely,

the duties) of conjugal experience. This is often an unattainable love, and such tension—between

eroticism and spirituality—tends to create images that now seem contradictory or paradoxical—best

witnessed, perhaps, in Petrarch's 14th century collection of lyric poems dedicated to his beloved, Laura.

For instance, a love as something that burns and freezes. Other Petrarchan conceits that derive from but

further explore the conventions of courtly love are: love as a battle and the beloved as an enemy; love

as deadly—a wound, a disease, a torment; love as bondage; love as a hunt and the beloved as the

elusive quarry; the beloved as a master, the lover as a slave; the power of the beloved's eyes or gaze;

the beloved's physical beauty (comparing parts of the body to jewels, flowers, snow, etc; the blazon);

the beloved as virtuous, not sexually attainable; the beloved compared to a sun or a star that orders the

lover's existence, and so on. NOTE: I am not saying that Petrarch's poems are expressions of courtly

love, but that they derive from and adapt its conventions and central themes.

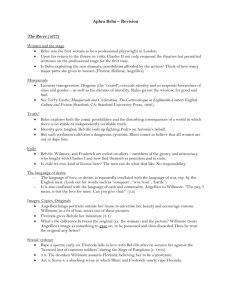

The gender dynamics of courtly love are therefore especially worth examining for what female writers do

to it—like Behn. The lady is “put on a pedestal” and the lord subjugates himself to her as an ideal. The

lord, knight, or lover is virtually always a man, and the lady—the idolized—is a woman. The narrative

or poetic forms of courtly love tend to be very conventional in this way. Later authors, like Petrarch,

gave new dimension to the tropes of amour courtois by overturning their conventionality and

emphasizing psychological realism. However, rarely did women take on the role of lover.

In Behn's The History of the Nun; or, the Fair Vow Breaker, we can clearly see elements of the tradition

of courtly love in conflict with the material realities of Isabella's life. In the dedication, Behn describes

herself as a courtly lover of sorts who admires the Duchess of Mazarin from afar, radically upsetting

conventional gender dynamics. The Petrarchan images throughout—being divided from oneself, love

that causes pain, the glance and the gaze as secret communicators, love as a hunt—are associated not

primarily with men, but with women, and Behn—like other educated people of her day—would have

been very familiar with the Renaissance and early 17th century translations of Petrarch from the Italian.

We might think about Isabella's impossible situations as situations made visible by her taking an active

role in a tradition that is unavailable to her.

In 1711, Richard Steele—a famous essayist and playwright—wrote an essay published in The Spectator

about female writers, in which he stages a debate between a female writer named Arietta—who is a

prudent but agreeable and entertaining conversationalist—and a young man who recounts to her the

story of the Ephesian Matron, a story typically held up as a byword for feminine inconstancy. She takes

issue with this, principally because it is a story that serves the interests of the patriarchy, and goes on to

tell her own story about constancy. What is interesting is how she articulates the power of narrative, the

power of storytelling:

You Men are Writers, and can represent us Women as Unbecoming as you please in your

Works, while we are unable to return the Injury. You have twice or thrice observed in

your Discourse, that Hypocrisy is the very Foundation of our Education; and that an

Ability to dissemble our affections, is a professed Part of our Breeding. These, and such

other Reflections, are sprinkled up and down the Writings of all Ages, by Authors, who

leave behind them Memorials of their Resentment against the Scorn of particular

Women, in Invectives against the whole Sex. (No. 11, Tuesday, March 13, 1711).

Writers have power, and can “represent us Women as Unbecoming as you please...while we are unable

to return the Injury”--that is, women cannot represent men as unbecoming. Writing withstands time,

and the ideas and prejudices passed down through it. The stories men tell become “memorials” making

tactile and true the various “Resentments” and “Invectives” against women. We heard last week about

the reluctance of women to publish, in part because to do so is to expose themselves to the marketplace

of print in a decidedly unladylike fashion. Those women who did write for the public had to navigate

treacherous waters. Women write, as they live, under the sway of patriarchal society. As Jane Spencer

notes in The Rise of the Woman Novelist: From Aphra Behn to Jane Austen, “there were common

expectations about women's writing: their main subject would be love, their main interest in female

characters. The idea that women...could exert a salutary [beneficial] moral influence on men...was

spreading; and so was the idea that it was through women's tender feelings and their ability to stimulate

tender feelings in men, that this influence operated. Hence, women writers who wished to claim a

special place in literature...were constrained by the twin requirements of love and morality.... Women

writers had the delicate task of balancing a 'feminine' sensibility to love with an equally 'feminine'

morality.” (Feminist Literary Theory: A Reader 121). Not only is there a fundamental tension here, and

one that is peculiar to women writers of the period, but the requirements of content and resolution

dictate that the “lesson” of any piece of women's writing must be acceptable. What happens at the end

of this amatory fiction? Isabella confesses her sins, and is executed. She has been justly punished for

breaking her vows. This is the official moral of the story. But is that all we can get out of it? Can we

read it against the grain?

Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, two pioneering feminst critics of the 1980s, addressed just this

question by theorizing what they call “the female swerve.” Their important 1979 text, The Madwoman

in the Attic, attempts to answer “the question of how women enter into the creative process, given that,

within patriarchy women’s writing cannot fully express itself. How can we understand the woman

writer who, defined always by men, is uncomfortable defining herself and who lacking a penis

(symbolized in the authorial pen), is anxious about whether she can create literature at all?” (242).

Essentially, they argue that in order to enter into the creative process as women defined by a patriarchal

system of values, tastes, and beliefs, female authors use a “‘cover story’—coded messages disguising

their intent” (242). Women's concerns—dispossession, the problem of desire in a culture both punishes

its existence and criticizes the “deception” that would conceal its existence, eternal subjection to an

authority that is not their own, and so on—have to be coded “so that their literature could be read and

appreciated” (290). In other words, in order to be allowed to speak, women writers had to speak

through the sanctioned images of women, the sanctioned narratives about femininity. For the woman

writer, “concealment is not a military gesture but a strategy born of fear.... Similarly, a literary ‘swerve’

is not a motion by which the writer prepares for a victorious accession to power but a necessary

evasion” (292).

So, this is an important methodological approach in feminist literary criticism—looking for the gaps,

the internal contradictions, the places where the official and the subversive meet—and it can offer us

helpful insight into The History of the Nun. We saw what happens at the end of the story, and Behn

prepares us for this at the very beginning—we'll be reading a story about the punishment of sacred

vows. But let's see what else might be going on underneath this cover story.

Behn is writing from a Protestant, even anti-Catholic perspective, and this is largely because of a

variety of political upheavals that happened in England over the course of the 15th, 16th, and 17th

centuries. The question of religious identification was very much alive in late 17th century England, and

there was much anti-Catholic sentiment—notably, because of the “Popish Plot” which led in many

ways to the Exclusion Crisis and the Test Acts. The so-called “Popish Plot” was the name given to a

rumored conspiracy in which Catholics were going to overthrow the government—under Charles II, the

English court had become much more Continental and Francophilic, and the King had issued a

declaration of religious tolerance in 1672, which led to general worries that England could become a

Catholic country again. Titus Oates was the main perpetrator of the fraud—he circulated a manuscript

that described the Catholic Church as having issued a hit on Charles II, and the story quickly took hold

in a country and culture that had seen many religious conflicts since the Reformation. Oates “named

names,” and after a key Protestant member of Parliament was murdered, suspicions ran rampant.

Various Catholic peers and lords were imprisoned in the Tower and five were ultimately beheaded. On

Guy Fawkes' day in 1678, the mob burned effigies of the Pope. Anti-Catholicism became more

virulent, and Parliament tried to pass a bill—the Exclusion Bill—that would exclude Charles' Catholic

brother James from the throne. This didn't pass, but its effects were long-lived, and the debate it

inspired became the crucible of modern politics. The Test Acts of 1672 and 1678, which restricted all

public employment—including the House of Lords and Commons—to only those professing

conformity to the Anglican Church, were passed, and not repealed until the 19th century.

So, the fact that Behn situates her tale (WHERE?) in a Catholic country, specifically Belgium—Ypres,

and in a nunnery called (WHAT?) St. Augustine's, is very far from coincidental. Let's look a bit closer.

The monastery is named after St. Augustine—can anyone tell me about him?

The Confessions and City of God his two most well-known works, but throughout his writings, he

asserted that carnal desire, even in marriage, is a sin. Yet, he had and struggled with his own sexual life,

well documented in The Confessions. It was Augustine who, as one scholar notes, “created the classic

patristic doctrine on sin, a morality in which especially sexual desire was condemned,” and who firmly

believed that men naturally rule over women. In On Concupiscence, he writes: “Nor can it be doubted,

that it is more consonant with the order of nature that men should bear rule over women, than women

over men...Wherefore, if one woman cohabits with several men inasmuch as no increase of offspring

accrues to her therefrom, but only a more frequent gratification of lust, she cannot possibly be a wife,

but only a harlot.”

“This Augustine who had made love to women and perhaps to men, who could not control his own

sexual problems, who was constantly torn between lust and frustration, who could in all sincerity pray:

‘Give me chastity . . . . , but not yet!’ (Confessions 8,7), who only became devout after he had ravished

whores to his heart's content, when his weakness for women, as so often happens to older men in later

life, turned into the opposite . . . , this Augustine created the classic patristic doctrine on sin, a

morality in which especially sexual desire was condemned. Augustine has influenced Christian

morality decisively, as well as the sexual frustrations of millions of Europeans unto our own day.” (K.

Deschner, De Kerk en haar Kruis, Arbeiderspers, Amsterdam 1974, pp. 326-327).

Behn's History of the Nun clearly depicts a woman who has sexual desire, who cohabits with more than

one man, and who miscarries; yet, she is treated sympathetically, which we can explore.

What is the point of his most famous theological treatise, City of God?

A theological treatise on the conflict between the “city of man” and the “city of god,” in which the city

of god would inevitably win, despite apparent setbacks in the earthly realm. For Augustine, the

Catholic church is the heart of the City of God, and it is peopled with those who deny earthly pleasure

and vow themselves to God. The City of Man, however, is peopled with those who embrace the

transient but material concerns and pleasures of the world.

Can we see these conflicting elements in History of the Nun?

Now, let's take a closer look. Who is the first man to stimulate Isabella's desire? Villenoys. Would it

surprise you to note that his name translates to “drowned” or “sinking” “city”? Why might she have

chosen this name?

Behn seems intent upon illuminating some of what she saw as the hypocrisies of a world governed by

doctrines that make it impossible for women to live freely as both desiring and devout individuals. The

nunnery is a place that fosters worldly pleasures—they dance, converse elegantly, mingle at the grate

with the nobility, write and perform plays, sing, and so on; yet, once having taken the vow of chastity—

at, Behn repeats twice, the ripe old age of 13, it cannot be broken without severe punishment, death,

damnation.

Yet, she cannot do this kind of critique explicitly; she must do it covertly, clandestinely, between the

lines, as it were.

the grand source of female depravity,

namely the impossibility of regaining respectability by a

return to virtue, although men preserve theirs during the

indulgence of vice. This made it natural for women to try to

preserve something that when lost can never be regained,

namely reputation for chastity; this became the one thing

needed by the female sex, and the concern for it swallowed up

every other concern. But. . . .neither religion nor virtue, when

they reside in the heart, require such a childish attention to

mere ceremonies, because the behaviour must on the whole

be proper when the motive is pure. (Wollstonecraft, Vindications Chapter 8)

“in women honestye once stained dothe never retourne againe to the former astate” (Castiglione, Book

of the Courtier First Book)