Men Should Weep-Pupil Booklet

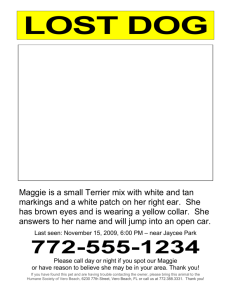

advertisement

“Men Should Weep” By Ena Lamont Stewart PUPIL BOOKLET Ena Lamont Stewart Ena Lamont Stewart was the daughter of a Church of Scotland minister whose family was originally from the Highlands, and had lived in Canada but who settled in Glasgow. Her family were middle class but Lamont Stewart was disturbed by the poverty she saw around her in the Gorbals. Later, she became a receptionist at the Sick Children's Hospital in Glasgow, where she saw firsthand the damage done by malnutrition and the many other diseases exacerbated by poverty and poor living conditions. She was married to an actor who was a member of Glasgow Unity Theatre –the company for whom “Men Should Weep” was written. ELS wrote because she felt the plays she saw on stage were unrealistic. Like many other writers of the time her work focuses on the harshness of the depression on the working class to try and impress on the middle class audience just how the working classes had suffered. ELS’s work is important because, unlike most work of the time, it presents a female perspective on social issues and their effects on women of the time, their families and gives us a view of how women’s lives have been defined by the success and failure of their men. In this respect ELS was before her time. Introduction - “Men Should Weep” Men Should Weep is a classic “slice of life” drama. Through the Morrison family it demonstrates what life was like living in the poverty of an East End Glasgow tenement in the depression of the 1930s. Maggie Morrison is mother to seven children ranging from infancy to adulthood. We see her trying to hold the family together and do the best she can while coping with unemployment, poor living conditions, disease, nosey neighbours, a sister who thinks she knows best and a rapidly changing society. The play is not sentimental nor humorous but it does give a real sense of the humour and sense of community apparent at this time. Men Should Weep is set in the East End of Glasgow, specifically in the Morrison’s tenement living room. Maggie works extremely hard taking care of her children, husband and elderly mother in law. Maggie’s husband, John, is out of work and struggling to find employment meaning the family survive the best they can on little and the occasional handout from Maggie’s sister, Lily. The setting of a 1930s Glasgow tenement and the stage directions indicating clutter at the beginning of Act One makes us feel the messy, claustrophobic, tense atmosphere the family live in. Maggie tries to take care of her family amidst such chaos but never finds time to complete any but the most necessary tasks. Neighbours constantly appear to share a cup of tea, catch up on the gossip while families struggle to find food to eat, and the woman upstairs is getting beaten by her husband after he’s had too much drink. This setting gives us a feeling of people struggling through from day to day trying to make ends meet while bringing up their family in a respectable way and also helps us understand the pressures such issues put upon relationships within the drama. The play exemplifies a number of trends of contemporary Scottish theatre specifically social and political dimensions [social background/conditions: poverty, living conditions, distribution of wealth, relationship between the individual verses the establishment etc]. Issues of gender are also a major focus as we explore traditional gender roles, changing attitudes towards gender and the impact of social, political factors on gender relationships. The action of the play begins one winter evening in the 1930s and we follow the action through to Christmas Eve of the same year. All the action takes place in the kitchen of the Morrison’s house in the East End of Glasgow. Brief Character Outlines Maggie Morrison matriarch of the Morrison family. Maggie loves her family and would do anything for anyone of them. She loves her husband a great deal and defends him to her sister, Lily. Maggie works hard and tries to do the best she can for her family. John Morrison “head” of the Morrison family. He is a handsome man who is struggling to find his role in life since he has become unemployed and unable to provide for his family. He believes that a woman’s place is in the home and that men should earn the money. Lily Gibb is Maggie’s spinster sister. She works in a pub, which given she is a woman is somewhat unusual for the time. Lily represents the changing role of women as she provides for herself and also helps out with the family by bringing them food and medicine for Bertie. Maggie talks of a “ yon disappointment” which could account for Lily’s attitude towards men. Alec Morrison is Maggie and John’s eldest son. He’s married to Isa. He’s a bit of a waster –the only “work” he appears to do is stealing and gambling. He squanders this money on drink or expensive things for his wife whom he is totally besotted with. He’s a complete mummy’s boy and manages to wrap Maggie around his finger. Isa regularly accuses him of being soft, however, we see he has a violent temper. Isa Morrison is married to Alec. She’s not a particularly nice character and believes that Alec should be spending money on her. She uses her looks and sexuality to manipulate Alec by threatening to leave him. Isa is disrespectful to Maggie, the neighbours and the older generation showing the changing attitude of the younger generation towards their parents. She also tries to control John by using her feminine wiles. Jenny Morrison is the Morrison’s eldest daughter. At the start of the play she lives with the family and is working in a fruit shop. Jenny is fed up living in the poor conditions of the Morrison’s tenement and giving her earnings to the family. Increasingly Jenny becomes more independent and, when socialising with Isa, increasingly disrespectful to her elders. She leaves the family home much to the anger and upset of her family. At the end of the play a more mature and respectful Jenny returns with money for the family to flit to a better house, something the family initially view as unacceptable because they feel Jenny gained it through improper means. Granny Morrison, John’s mother who lives part of the time with the family and the rest of the time with her daughterin-law, Lizzie. Granny can’t really fend for herself and spends a lot of the play bemoaning how it’s terrible to be old and a burden. She dislikes staying with Lizzie because Lizzie takes her pension. She comments on political issues when talking about Lloyd George’s introduction of the pension. She also shows society’s attitude towards the elderly. Lizzie Morrison John and Maggie’s sister-in-law. She’s quite unpleasant and views Granny as a burden. She’s out for what she can get money wise. Given the poverty of the time this may seem logical but Lizzie is viewed by other characters as a selfish miser willing to profit from the misfortune of others. Mrs Harris one of the neighbours. Mrs Harris’ daughter has nits –highlighting the social issue of hygiene. Good friends with Maggie and although they argue the neighbours are always popping in for a cup of tea and to help each other out. Mrs Bone the upstairs neighbour. She’s regularly beaten by her husband but doesn’t think this is anything out of the ordinary. As with Mrs Harris and Mrs Whiter she’s always there to help Maggie. Mrs Wilson another neighbour. The neighbours are described by Maggie as “coorse but kind”. Edie & Ernie Morrison daughter and son of Maggie and John. Edie is skinny and 11. Ernie is a typical boy, into football and jazz music. Marina & Christopher Morrison the babies. We don’t see them but hear them behind the curtain. Bertie Morrison, mentioned but never seen he’s the Morrison’s son who is suffering from TB. He eventually gets taken into hospital and won’t be released home until the family move to better housing. Plot Overview Act 1: Scene 1 One winter evening – 1930s– Morrison living room/kitchen– This scene shows the poverty of the family and the social conditions of the time. It also introduces Lily Gibb, Maggie’s spinster sister, who has a dislike for all men and they way they behave. When John, Maggie’s husband who has been out looking for work, comes home he teases Lily and she leaves. We also meet the neighbours, Mrs Harris and Mrs Wilson who have come in excited to tell Maggie the news that her son Alec’s tenement building has collapsed. Maggie begs John to go round and look for Alec. Once John leaves, the conversation between the women introduces the subject of Maggie’s older daughter, Jenny, who works in a fruit shop. Maggie and Mrs Harris have a fall out when Maggie informs her that the teacher at school has said the Mrs Harris’ daughter Mary has beasts in her hair. She suggests that Mrs Harris “get something from the chemists” before she “gets the sanitary” on her. We also find out about young Bertie’s state of health i.e. he’s suffering from a chest complaint, which judging by both the neighbours and Lily’s reaction to the coughing, could be quite serious. Act 1:2 The scene starts with the arrival of Alec, Maggie’s eldest son, and his wife, Isa. The couple are having to move in with the family until their house is repaired. It is clear that Alec adores Isa while she despises him for being a weak individual and for, it seems, being so besotted with her. Maggie, however, clearly worships her boy and feels he can do no wrong, despite the fact that he has apparently had too much to drink. John further highlights the over-crowding problem, “Is he gonnae lie aside Bertie stinkin’ o stale beer?”. John and Maggie then settle down and John asks about Jenny. He presumes that she’s already in bed given the late hour and we can clearly see how much he adores his daughter. Maggie is afraid to tell John that, his “pet” has not yet returned home from a night out. John is starving so cooks the beans Lily brought for the family as a treat. This is interrupted by Bertie’s coughing. This reminds us of his poor state of health and this is further highlighted by John suggesting Maggie takes Bertie up to the hospital. John now realises Jenny is still out – this angers him as he doesn’t believe this is behaviour befitting a young girl. We also learn that Jenny wishes to leave home, this further angers John. Jenny makes her entrance coming down the close talking and laughing with a young man. John is furious. He goes down to the close and brings Jenny home. They have a heated exchange where Jenny makes her feelings about living in the house clear: “ I dinnae ask tae be born, no intae this midden. The kitchen aye like a pig sty –there’s never ony decent food, and if there wis, ye’d hae nae appetite for it…an’ sleepin’ in a bed –closet in aside a snorin’ auld wife. Naw, I’ve had enough. I’m gonna live ma ain life”. John hits her, she marches off. The scene ends with Maggie going to bed as John lights a cigarette and stares out of the window. Act 2: Scene 1 Granny is waiting, cases packed, bed-ends and mattress propped up against the wall, to be taken to Lizzie’s house as there is no longer any room for her in the already over-crowded Morrison house. Mrs Bone and Mrs Harris are keeping her company as Maggie is at the hospital with Bertie. Lizzie is forced to take her turn looking after Granny and uses the opportunity to use what little money Granny has in the form of her pension by insisting that Granny hands over her pension book. When Lizzie appears she discovers that Granny has already drawn her pension this week to help Maggie buy things for Bertie going to his appointment at the hospital. Lizzie decides to “take what Maggie has bought” to replace the missing pension money however the neighbours refuse to let her take a thing. Lily enters and we see the hostility between the two characters. The scene continues with Jenny, Isa and Alec coming in arm-in-arm. The girls are sharing a joke in which Alec is not included, something he’s clearly unhappy about. Isa asks “Whaurs ma dear mither-in-law –oot at the jiggin’?” This shows the hostility she has towards Maggie and also the lack of respect she has for her elders. Jenny is shown to be just as rude and Mrs Bone and Mrs Harris decide to leave stating “You’re a right cheeky wee bizzim Jenny Morrison. Serve ye right if the next time your Mammy’s needin’ me or Mrs Bone, we’ll no come and you’ll need tae bide in. Jenny replies “Oh, but I’ll no be here! I’ve seen the last o you auld teasookin tabbies. This little birdies flyin awa fae the nest…Pit that in yer pipe and puff it oot tae the neighbours”. The removal men arrive to take Granny’s belongings to Lizzie’s then Maggie returns home with the news that Bertie’s been kept in with TB. Maggie is devastated at the thought of Bertie being away from her and she regrets her reluctance of “getting up tae him in the night”. She pleads with Jenny not to leave home but Jenny is still determined to go and make a better life for herself. John comes home to hear the news about Bertie just as Jenny is leaving. Once she’s gone he states, “she’s deid tae me. If I could jist…jist done better by ye a’”. Act 2: 2 Morrison house, one month later. Alec and Isa are quarrelling in the bedroom. Isa appears with Alec behind her. She complains to him about their poor quality of life. It also emerges that Alec has robbed someone. When Isa threatens to leave him for Peter Robb Alec grabs her by the throat showing his temper and violent side. He lets go after nearly strangling her. She exits. Maggie enters –tired and shabbily dressed. The house is a mess waiting for her to come home to tidy it. Alec is in a state and wants Maggie to buy some cigarettes when it becomes apparent that she doesn’t think this a necessity Alec plays on Maggie’s concern for him persuading her to send Isa out for cigarettes and whisky. Isa and Maggie quarrel over the way Isa treats Alec, threatening to leave him. Isa: Maggie: You keep yer insultin names tae yersel ye dirty aul bitch! I’ll learn ye tae call me a bitch! (she slaps Isa) At this point John enters and instead of leaping to his wife’s defence he supports Isa saying Maggie is certainly acting like one. Maggie is angered and they have words about the state of the house. In reply to Maggie’s suggestion that he could have tidied up given she had been out working John says: “Taw hell wi this Jessie business every time I’m oot o a job! I’m no turnin masel intae a bloddy skivvy! I’m a man!”. This argument continues with John dragging Alec out of the bed objecting to him being drunk. Maggie’s response to this is “Who earned the money? You or me?”. This is a slap in the face for John who has no work while Maggie earns at least something from her part-time cleaning jobs. John finds this so hurtful because as head of the house he is supposed to be the breadwinner. While this has been going on, Alec has stolen some of Maggie’s cash and has snuck out. Maggie goes leaving John and Isa. Isa flirts with John, teasing him about his status. Maggie comes back with groceries. When Edie and Ernie enter and Maggie sees Ernie’s boots all scuffed from playing football things reach a peak and she screams at him before exiting in tears. John calms the children and they go about beginning dinner and making tea. Once she’s calmed herself Maggie returns and attempts to restore her sense of humour when she refuses Edie’s offer of chips: “No hen, I’m no for a chip. The gie me the heartburn. I wonder whit kind o male idiot called indigestion heartburn! Ma Goad! I could tell him whit heartburn is! Ma Goad! Couldn’t I no!” Act 3 Christmas Eve at Maggie’s house. A different picture. The room is tidy and decorated for Christmas. A wireless is in view, Ernie has new football boots. Maggie is wearing a new dress. Granny is back. John comes in –he has a present for Maggie –a new red hat to remind her of the one she wore when they were courting. John is back in work in a delivery job. “It’s Christmas and John’s got a job. We’re gaun tae have a merry Christmas”. Mrs Bone and Mrs Harris come in for a cuppa and Maggie offers them Christmas cake. This is a stark contrast from Act One when she had nothing to offer and the neighbours had to have a sweet they had leftover from a trip to the cinema. Mrs Harris: Maggie: Did you get a parcel from the Mission? Naw, John brung it up frae Liptons. Eat up. Come on! The neighbours also comment on Maggie’s new hat, comments are also made on the role of men. Lily comes to join them with a present for Maggie –yellow cotton gloves. The women examine the gloves and make some derogatory comments about where Lily bought them and the price. Clearly being poor is no shame but being tight with money is. Alec enters in a mood looking for Isa. We also find out that Bertie has been to the Sanitorium –Maggie is hopeful that he will be home soon. Alec leaves in a fit of temper. The women talk about having seen Jenny “ ‘roon the Poly”. The conversation is then interrupted by a thumping from upstairs – Mrs Bone’s husband looking for her, “Oh Goad! That’s him wakened. See ye later. Ta for the tea.” Mrs Wilson also goes incase her man’s waiting on his tea. As Mrs Harris leaves she says “It’s him that’s wanting me. I’m no needing him ‘cept for his wages. Ta ta Granny”. Maggie and Lily plan to put Granny to bed so that they can go out shopping. They give her an aspirin and take her off to bed. Some time passes then Isa enters looking well dressed. She goes to the bedroom and comes back with a shabby suitcase –Alec makes a surprise entrance. When he sees Isa he confronts her and becomes violent, threatening her with a knife. He tries to choke her but releases her. Realising she has to escape Isa appeases Alec by pretending she’s kidding him on and that she’s not going to leave him saying she’s got them a “room and kitchen”. Eventually she sees her chance to escape and takes it leaving Alec sobbing. The lights fade. Maggie and Lily come back from shopping. Lily finds the knife and puts it in her bag. Maggie realises that Isa’s clothes have gone. As she’s comforted by Lily, Maggie acknowledges that she’s spoiled Alec and that he’s too weak for his own good. There is then a knock at the door –it’s Jenny. Jenny has been to the hospital, she realises that Bertie will not be allowed home to the damp “midden of a house”. As Jenny explains, “Mammy seems to think they’re lettin’ Bertie hame; but they’re no. No here tae this Mammy, ye’ve tae see the corporation for a council hoose”. Jenny has come to make peace with her family by offering them money to start a new life in a decent house. Both Lily and Maggie comment on where this money has come from –Jenny’s “fancy man”. Maggie: Lily: Aw Jenny, I wisht ye’d earned it. Oh, she’ll have earned it Maggie, on her back. As Jenny is explaining how she has the money for flitting to a rented house John enters. Jenny tells him how she plans to get a decent house for Maggie and the kids –John is furious, “I’d an idea I wis the heid o this hoose”. Maggie explains that the hospital is not letting Bertie back to the tenement but John will still not accept Jenny’s money, “Ye can take that back tae yer fancy man. We’re wantin nane o yer whore’s winnins here”. Maggie then makes a stand by confronting John about their past, she realises that if the family are to come together she has no choice but to take Jenny’s way out: Whore’s winnins did ye ca this? And did I hear you use the word ‘tart’? Whit wis I when we was coortin but your tart? John is shocked as Maggie tells him a few home truths. He has sunk into a chair covering his face with his hands. Immediately she regrets it but the point has been made. It’s a turning point in the whole play –it’s the beginning of Maggie’s journey to a new life and she knows she will get her own way. Dinna fret yersel Jenny, I can aye manage him. Four rooms did ye say Jenny? Four rooms. Four rooms… and a park forbye! There’ll be flowers come the spring.” When studying the text we are focusing on SOCIAL, POLITICAL and RELIGIOUS dimensions as well as ISSUES OF GENDER. Make a list of the KEY EVENTS in Act I that exemplify these trends. Repeat this for Acts II and III. List events under the correct headings, some examples have been given. Remember to state which issue is being highlighted. SOCIAL, POLITICAL & RELIGIOUS DIMENSIONS Act 1:1 – John has been out looking for work he’s not found any [Unemployment] -Alec and Isa’s tenement building has Collapsed [Poor Housing] ISSUES OF GENDER Act 1:1 –Maggie is cleaning, looking after the children [Marriage & the Fam] Tension Graph 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Act/Scene 7 8 9 10 CST Trends Graph Social, political, religious 10 No. of occurrences Issues of gender 0 Act & Scene Examine how tension levels in the play relate to the occurrences of different CST trends? What does this tell us? GLASGOW UNITY SHEETS TO GO HERE!!!! Analysis How does ELS highlight social, political, religious dimensions and issues of gender? Expand upon the KEY EVENTS list you began earlier by including KEY QUOTES to exemplify the point you are making and by giving detailed analysis (PEA). Use your SPR and Gender booklets to help you. Remember, writers communicate their message in a variety of ways: PLOT, ACTORS (CHARACTERS) LANGUAGE SETTING/STRUCTURE/STAGE DIRECTIONS SOCIAL, POLITICAL & RELIGIOUS DIMENSIONS SOCIAL BACKGROUND & CONDITIONS [e.g health, housing, hygiene, unemployment, living conditions, poverty, care of the elderly, community, over-crowing] NATIONALISM [attitudes to Scotland as a nation, how the Scottish people are represented] INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS & THE WORKPLACE POLITICAL THEATRE AS ENTERTAINMENT RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE INDIVIDUAL & THE ESTABLISHMENT [relationship between chs and government,relationship between chs and authority] DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH [who has money? how are they viewed/portrayed?] SECTARIANISM [religious issues, how are they discussed/represented?] DEVICES USED TO COMMUNICATE SOCIAL, POLITICAL & RELIGIOUS MESSAGES [how is ELS conveying messages about social, polit& religious issues? What techniques does she use? Give evidence] ISSUES OF GENDER GLASGOW UNITY SHEETS TO GO HERE!!!! SYMBOLIC MARTYR RELATIONSHIPS OPPRESSION & SUFFERING WOMEN & POWER MEN & POWER ROMANTIC HERO RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE ESTABLISHMENT MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY SEXUAL DEVELOPMENT OF CHARACTERS Revolt of the washerwomen – The Guardian, Sat 27 th August 2005 Why were the angry young socialists of the 1980s so enthralled by a forgotten Scottish play about downtrodden housewives? Dominic Dromgoole recalls the magic of Men Should Weep Every young generation has its own collection of landmark cultural moments, a cluster around which it forms its identity. Heaven knows what it is today - some strange blend of Sarah Kane, McFly and Big Brother. But 20 years ago, one event stood out for those of us pursuing our daft dream of changing the world through theatre. In those dead days of short hair and Doctor Martens, buckets being shaken for miners' wives outside Cambridge colleges and painfully earnest productions of Shakespearean comedies, a clarion call was sounded in Edinburgh towards which many flocked. To suit the anti-chic of the age, it was the most fastidiously unglamorous event conceivable: a revival by the radical Scottish company 7:84 of a lost classic play by an unknown writer, Ena Lamont Stewart. Its subject was life in the Glasgow tenements in the late 1930s. Its title was the perfect fit for an age of masculine self-abasement: Men Should Weep. How we nodded. Several streams of enthusiasm ran towards this event. John McGrath, the giant who ran 7:84, was already a cult figure thanks to his book, A Good Night Out, a thrilling guide to creating popular, committed, subversive theatre. Everyone carried a copy round in their jacket pocket, dog-eared by midnight reading. The director of the play, Giles Havergal, was a star from the Glasgow Citizens, a theatre already reinventing the plastic and visual possibilities of British theatre. And the content of the play was perfect for an age when to be male and middle class was punishable by a lot of pointing and giggling. It was about women's struggles to help their families endure poverty when they were oppressed by economic failure and the collapse of their men. To cap it off, they were Scottish, in an age when to be Scottish and working class was short-hand for an authenticity of which every Sassenach sissy could only dream. Many of my friends saw Men Should Weep when it first appeared in Edinburgh, and spoke wildly and enthusiastically about it. Several travelled up to Scotland to see it on its subsequent tour. When the news arrived that it was coming to London - and playing at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East (another temple of sophisticated popular entertainment) people practically combusted with revolutionary theatrical excitement. Pilgrimages were organised. Unfortunately, my money had run out weeks before, and the prospect of spending my last pounds on anything other than speed and chips was inconceivable. So I waved goodbye to a bus half full of overexcited fellow students, and returned bedsitwards to read the play alone. I picked it up, expecting a Brechtian epic of incendiary agit-prop. What I read initially confused me. This was no speechifying call-to-arms, no pained argument about sexual politics. This was a gentle and human tale about a group of people living a life in extraordinary circumstances. This was recorded experience, not manipulated experience. My confusion soon turned to admiration, but the privacy of the pleasure seemed at odds with the public brouhaha. Rereading the play today reinforces the impression that Men Should Weep is a classic of 20th-century theatre. Oddly, having been rescued from neglect 20 years ago, it has fallen into literary oblivion once more. It may be that the politics of the first great revival became too strongly stuck to the play, and obscured its quieter, more human qualities. It was an ideal play for a time ravaged by Thatcher's swivel-eyed monetarist experiments in social misery, but it speaks about more than recession. It is also a timeless play about family, survival, delusion and dignity. Now it is time simply to admire its greatness. Ena Lamont Stewart was the daughter of a Church of Scotland minister whose family was originally from the Highlands, and had reached Glasgow via a considerable detour to Canada. This gave her the simultaneous perspective of both an outsider and insider. Theirs was an open house, filled with morality and noise. As she said: "We laughed a lot, talked a lot and read a lot. We also sang a lot and had, in addition to the piano (which was played a lot), an organ, two sets of bagpipes and a penny whistle." It's a music that is embedded in the language of her plays. Although her family would have qualified as middle class, Lamont Stewart was disturbed by the poverty she saw around her in the Gorbals, ravaged by the effects of the Depression. She was struck by the sight of working-class "shawly women", who jostled into her father's jumble sales, rooting out the best bargains. Later, she became a receptionist at the Sick Children's Hospital in Glasgow, where she saw at first hand the damage done by malnutrition and the many other diseases consequent on poverty and poor living conditions. Here she found the material for her first play, Starched Aprons. And it was here she first heard the phrase, "They've kep' him in", muttered incessantly by a dazed mother trying to pass her a scraggy bundle of clothes for her child, who had been told he had to stay in the hospital. The phrase becomes the emotional bedrock for the last act of the play. Her plays observe life with the cruel lack of sentimentality of Sean O'Casey, and celebrate it with the same richness of language. In another parallel to the great Irishman, her need to write was closely linked with a strong root-and-branch socialism. Her husband, an actor, worked for the Glasgow Unity Theatre, an idealistic, socialist company formed by working-class actors, whose aim was to represent the experiences of the working class to the world. They were strongly averse to the refined, drawing-room-theatre manners of the day. Lamont Stewart herself wrote: "One evening in the winter of 1942 I went to the theatre. I came home in a mood of red-hot revolt against cocktail time, glamorous gowns and underworked, about-to-be deceived husbands. I asked myself what I wanted to see on stage and the answer was Life. Real Life. Real People." She wrote Men Should Weep in two days flat. This is not one of those painfully etiolated political plays where each phrase has been sweated through for its appropriate meaning. This is a play about life that poured out of its creator from imagination and remembered experience. As she said: "I couldn't possibly tell you what I was thinking about when I sat down to write it ... I wrote Men Should Weep at such a pitch of intensity I had no idea what the characters were going to do next ... I think it was a kind of emotional release I needed at the time." Her marriage was foundering, and she was about to become a single mother. Some of that desolation and fear must have been projected into the play. She had an extraordinary relationship with the characters she created. Of Starched Aprons she said: "It wrote itself. I saw my characters - as if they really were in front of my eyes, and I wrote down what they said. This sounds all too easy. What? No agony? I don't remember any agony while writing ... the characters just arrived in my kitchen when I was doing a washing - as if they were saying, 'Come on, we'll give her a couple of pages. She'll have to dry her hands and hunt for pencil and paper; then we'll buzz off.'" Her characters were people who "had walked into my head and commanded me to reach for pencil and pad. Characters in full flow cannot be ignored. They threaten, 'Get this down on paper, Ena. We're not going to be whistled back just when you feel like it, you know.'" The freshness of their voice, the truth of their manner, the explosive need-to-be-alive of each character gives testament to the accuracy with which she recorded what was said. As with the other plays that came from the Unity theatre, there was a fastidious realism about presenting the life of the working class. They depicted their suffering, showed how heavily the odds were stacked against them, and admired the courage and fortitude with which they deadpanned their way through the shitty hand they had been dealt. But they were also unsparing in exposing flaws, the apathy and the lack of purpose that led to drink, gambling and violence. Robert McLeish's The Gorbals Story dealt in particular with racial and religious problems. Men Should Weep concentrated on the lives of women. Amazingly, these two plays, together with other Unity works, proved huge commercial successes. They ran for long periods in Glasgow, toured the country, then transferred to London's West End. In the brief socialist dream that gripped postwar Britain, such things were possible. Yet success brought its own poison, and, like Joan Littlewood's company 20 years later, the Unity theatre withered on the vine in the West End, detached from its roots. Lamont Stewart's story was one of frustration. Her subsequent plays were turned down - one with such force, by James Bridie at the Citizens Theatre, that she went home and tore up all the copies. The men's club of theatre has always had an ability for briefly welcoming outsiders before closing the door on them. Lamont Stewart now lives in the twilight of her life in a Scottish nursing home, in a state further adumbrated by the clouds of Alzheimer's disease. One can only hope that her characters are still chattering kindly to her. Reviews of the National Theatre of Scotland’s 2011 Production Men Should Weep – Mark Fisher guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 21 September 2011 19.40 BST The tenement flat is claustrophobic, cramped and colourless. There is no room for manoeuvre between sink, table and bed, yet new people constantly arrive and are somehow absorbed. In Ena Lamont Stewart's 1947 slice-of-life tragedy, the inhabitants are caged creatures who can do nothing but lash out. So when Arthur Johnstone walks on stage between scenes to sing a working-class folk song, he brings a heady shift in perspective. On the one hand, he offers a release from the grim intensity of so much 1930s deprivation, piled on by Lamont Stewart in an unflinching vision of poverty's social consequences. For the audience to join in “The Day We Went to Rothesay, O'” is like coming up for air. On the other hand, Johnstone's songs put the play in a tradition of socialist dissent: "We've been yoked to the plough since time first began" goes The Workers' Song. These full-voiced songs emphasise that the hardships of Men Should Weep are not an anomaly, but part of a pattern. Like the scene of modern deprivation (shell suits, corrugated iron and barbed wire) that frames Graham McLaren's powerful production for the National Theatre of Scotland, the songs give this brutally unsentimental play a political and historical context. Likewise, playing the stoic matriarch Maggie, Lorraine McIntosh brilliantly conveys the sense of being a product of her economic circumstances. She is merciless in criticising her neighbours, ferocious in disciplining her children, and vocal in her complaint that there is "nae work for the men, but aye plenty for the women". Yet, behind her fury, she shows us a good-hearted woman making the most of the little she's got. As our own government demonises the poor, hers is an example as pertinent as ever. Men Should Weep Published in The Stage, Thursday 22 September 2011 at 11:42 by Thom Dibdin There is an inevitability to Graham McLaren’s hard-as-nails production of Men Should Weep for the National Theatre of Scotland. Even as the side of a rusty container surmounted by barbed wire is drawn back to reveal the two-room Glasgow Gorbals tenement inhabited by Maggie and her ever-growing family, you know that this place is toxic waste - that when happiness does shine it will soon be drowned out by sorrow. There is humour, of course, amidst designer Colin Richmond recreation of Scotland in mid 20th century depression. It is there in the 15-strong company’s revelling in Ena Lamont Stewart’s sharply observed Glaswegian vernacular, in the wry comments of Ann Scott-Jones’ not-quite senile Granny, and in the crisp details as Grant McDonald’s near-starving boy, Ernest, swipes chips from the meagre portion the whole family will have to share. There is love, too. At least between Lorraine M McIntosh’s resilient Maggie and Michael Nardone’s towering, yet broken John. A frisson of sexual tension still permeates their marriage of 16 years or more, plagued by spoilt, feckless and wayward children and living in a squalor which is killing their youngest child with TB. Louise McCarthy, Lorraine McIntosh, Michael Nardone and Julie Wilson Nimmo in Men Should Yet for all that Maggie and John can do, for all their faith in doing the Weep at Citizens Theatre, Glasgow right thing, for all the support they are given but can not use, and for all Photo: Manuel Harlan of Stewart’s rewritten 1970s happy ending, the focus is on grinding depression. This is a generation of men whose only crime, as John cries out, was to be born into poverty. And as such, it cries out a chilling warning to us now, in far more comfortable times. Teacher Notes for Discussion Social, Political, Religious Dimensions Social background & conditions: Housing, hygiene, unemployment Distribution of wealth: Maggie fears to go to the hospital because of the way she’s looked down upon. Nationalism: Relationship between the individual and the establishment: John’s relationship with the government Grannie’s attitude towards the government –Lloyd George Devices used to communicate social, political and religious issues: characters we care about/can identify with, humour –kids/Grannie/neighbours, language -familiarity setting- familiar, well know area of deprivation Political theatre as entertainment: Industrial relations and the workplace: Sectarianism: Issues of Gender Symbolic Martyr: Maggie is a martyr, sacrifices her own life for her children/family Romantic Hero: Inversion of the stereotypical romantic hero –the man rescuing the woman, the rescurer is consistently women (Lily brings food, Maggie gets a job to provide for the family, Jenny gets enough money for the family to move). Women achieve what John couldn’t, or wouldn’t. Relationships: Strong relationships between family and community Maggie and John’s relationship is very strong although they don’t see eye to eye Mainly stereotypical relationships but throughout the play and especially at the end these are tested Relationship between the individual and the establishment: Marriage and the family: Women and power: sexual power of Isa, Men and power: Physical power Sexual development of characters: Jenny begins to see she can change her circumstances Oppression/Suffering: