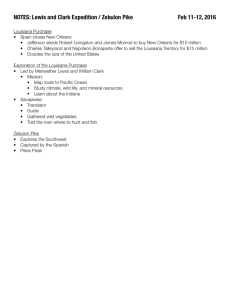

Education in Louisiana - Louisiana Department of Culture

advertisement