From Hunting Magic to Shamanism: Interpretations of Native

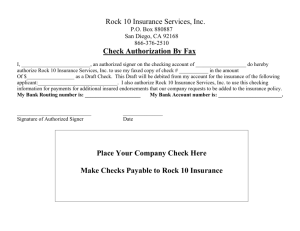

advertisement