labourand human rights standards internationally

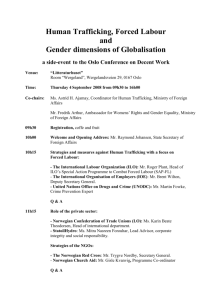

advertisement