annette c. baier - The Tanner Lectures on Human Values

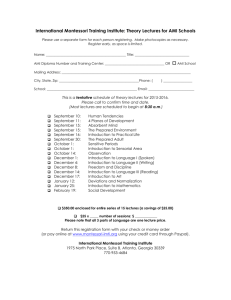

advertisement