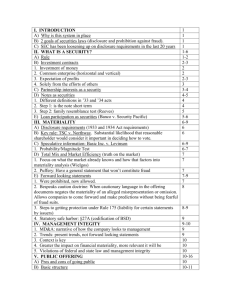

Trends In SEC Financial Fraud Actions: Part I

advertisement

Portfolio Media. Inc. | 860 Broadway, 6th Floor | New York, NY 10003 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | customerservice@law360.com Trends In SEC Financial Fraud Actions: Part I Law360, New York (April 29, 2011) -- Financial fraud has long been a staple of U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission enforcement. The formation of the Interagency Financial Fraud Task Force in November 2009 and the Virginia Financial and Securities Fraud Task Force in May 2010, both of which include the SEC and U.S. Department of Justice, are undoubtedly spurring the efforts of regulators in this key area. Many recent SEC financial fraud cases are built on traditional themes of improperly boosted revenue, cookie jar reserves and similar items. At the same time there are indications of a new or modified approach. In part this may stem from the market crisis from which some of these cases were developed. In part it may be a product of the overall enforcement environment. This series will examine these trends in two parts. Part I will consider the line between civil and criminal cases and the liability of directors and officers in cases alleging scienter. Part II analyzes cases involving officers where the claims are based on negligence or other charges and reviews selected financial fraud cases. The segment will conclude with an analysis of trends in this key enforcement area. The Line Between Criminal and Civil Cases The division between criminal and civil violations of the law in financial fraud actions, as well as others, is supposed to be governed by the willfulness standard written into the statutes by Congress when they were first passed. See, e.g., Exchange Act Section 32(a). In practice the line has all but vanished in the view of many commentators. Court decisions defining the criminal element of “willful” to include “willful blindness” and “conscious avoidance” and decisions in civil cases holding that “scienter” encompasses “reckless disregard” blur the division to the point of being virtually a distinction without a difference. See, e.g., U.S. v. Kaiser, 609 F. 3d 556 (2nd Cir. 2010)(discussing element in criminal case). In the context of these court decisions the dividing line between criminal and civil financial fraud becomes a function of prosecutorial discretion. This is typically measured in terms of the egregiousness of the underlying conduct. For example, the collapse of mortgage lender Taylor Bean & Whitaker Mortgage Corp. and the massive fraud at bulletproof vest manufacturer DHB Industries Inc. or Point Bank resulted in SEC enforcement actions as well as criminal prosecutions against former offers of each company. By virtually any definition the conduct in each case was egregious. SEC v. Farkas, Civil Action No. 1:10 cv 667 (E.D. Va. Filed June 16, 2010); U.S. v. Farkas, 10-cr-00206 (E.D. Va. Filed June 16, 2010); SEC v. DBH Industries Inc., Civil Action No. 0:11-cv-60431 (S.D. Fla. Filed Feb. 28, 2011); SEC v. Brooks, Civil Action No. 07-61526 (S.D. Fla. Filed Oct. 25, 2007); SEC v Schlegel & Hatfield, Civil Action No. 06-61251 (S.D. Fla. Filed Aug. 17, 2006); U.S. v. Brooks (E.D.N.Y). The criminal charges against Lee Farkas center on the collapse of the company he founded and ran, Taylor Bean, and its affiliate, Colonial Bank. The 16-count indictment alleged a $1.9 billion scheme which contributed to the collapse of both companies and involved an attempt to defraud the Troubled Asset Relief Program. In one part of the fraudulent scheme, Farkas is alleged to have shuffled money between Taylor Bean and the lender to conceal huge cash shortages. Another facet of the scheme involved the alleged misappropriation of hundreds of millions of dollars from a related loan facility and misrepresentations to the government in an effort to secure TARP funds. A jury recently returned a verdict finding Farkas guilty of conspiracy, bank fraud and securities fraud charges. The SEC’s case is pending. The conduct underlying the collapse of DHB Industries, which is at the center of the SEC’s actions as well as the criminal prosecutions, is similar in character. In those cases former company CEO David Brooks and his lieutenants have been charged with essentially looting the company and using millions of dollars for their personal benefit. Brooks, along with former chief operating officer Sandra Hatfield, have been convicted of criminal securities charges following a jury trial. The SEC’s action is pending. See also SEC v. Collins, Case No. 07 cv 11343 (S.D.N.Y. Filed Dec. 18, 2007) (financial fraud action settled following criminal conviction of the former Mayer Brown attorney who participated in accounting fraud which lead to the collapse of Refco). SEC v. General Re Corporation, Case No. 10 CV 458 (S.D.N.Y. Filed Jan. 20, 2010) (settled financial fraud action which is one of a series of civil and criminal cases based on two fraudulent financial schemes). Cf. SEC v. Styam Computer Services Ltd., Case No. 1:11-cv-00672 (D.D.C. filed April 5, 2011) (settled financial fraud action which alleged that a group of officers fabricated documents to falsify revenues over a period of years; a parallel criminal case is pending in India where the company is based). The commission’s civil financial fraud actions are also typically based on allegations of intentional wrong doing. See, e.g., SEC v. Diebold Inc. Civil Action No. 1:10-CV 00908 (D.D.C. Filed June 2, 2010) and SEC v. Gupta, Civil Action No. 8:10-cv-00100 (D. Neb. Filed March 15, 2010). The former is a settled financial fraud action which alleged that over a five-year period the manufacturer of automated teller machines improperly inflated income on certain transactions by recognizing revenue on lease transactions that were subject to buy back agreements, contrary to the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. The company is also alleged to have manipulated its reserves and improperly capitalized expenses. As a result Diebold was required to restate its financial statements. The complaint alleged violations of the anti-fraud and books and records provisions. The settlement was based on a consent to an injunction based on those provisions and the payment of a civil penalty. The latter is one of a series of financial fraud actions centered on alleged violations of the anti-fraud, proxy and reporting provisions by Vinod Gupta, the founder and former chairman of infoUSA Inc. The case focused on claims that over a four-year period Gupta received about $9.5 million in unauthorized and undisclosed compensation. In addition, the company, and another Gupta controlled, engaged in millions of dollars of undisclosed related party transactions. The case was settled with a consent to the entry of a permanent injunction prohibiting future violations of the anti-fraud, proxy and reporting provisions along with the payment of disgorgement and a civil penalty. While neither Diebold nor Gupta involves the kind of misconduct in the Taylor Bean or DBH Industries cases, both center on years-long intentional misconduct. The difference is one of degree. In some instances, what appears to be blatant financial fraud turns out to be much less. This is precisely what happened in SEC v. Collins & Aikman, Civil Action No. 07-CV-2419 (S.D.N.Y. Filed Mar. 27, 2007). There the SEC brought a financial fraud action against former OMB director and the former CEO and chairman of the company David Stockman as well as the company and other senior officials and board members. At the same time, criminal charges were brought against Stockman. All of the allegations centered on a claimed financial fraud which supposedly involved multiple fraudulent schemes. In January 2009 the U.S. attorney voluntarily dismissed its case. The SEC, however, continued to litigate its action for over a year before dropping all of the intentional fraud claims and settling for negligence based injunctions under Securities Act Sections 17(a)(2) and (3). While Stockman did agree to pay disgorgement, prejudgment interest and a civil penalty, most of the sum was offset by payments made to settle parallel class actions. If the settlement is little more than a face-saving effort by the agency, as it appears, it raises significant questions about prosecutorial discretion. The Liability of Directors and Officers — Intentional Fraud Financial fraud actions are typically brought against the company and in many instances the officers alleged to have been involved. Few cases are brought against individuals for their role as a corporate director. SEC v. Krantz, Civil Action No. 0:11-cv-60432 (S.D. Fla. Filed Feb. 28, 2011), however, is an action brought against the outside directors of DBH Industries Inc. The complaint in Krantz is based on what is claimed to be egregious conduct. Although each defendant was an outside director, the SEC claims that their independence was compromised by their personal relationships to the now convicted former CEO of the company, David Brooks. The complaint goes on to detail a series of blatant red flags presented to the board regarding the looting of the company by Brooks. Those included concerns expressed by the auditors, a material weakness letter and other indications of the fraud. In each instance the directors failed to take any meaningful action according to the complaint. The complaint alleges violations of the anti-fraud and reporting provisions of the federal securities laws. The case is in litigation. More typical is the complaint in SEC v. Conaway, Case No. 05 cv 40263 (E.D. Mich. Filed Aug. 23, 2005) which is a financial fraud action against the former CEO of Kmart Corp. in which the SEC obtained certain ancillary relief last year after prevailing at trial in 2009. The civil fraud claims against Conaway centered on a scheme to cover up the deteriorating financial condition of the company stemming in part from a massive inventory overbuy paid for on credit. At the time the company was suffering from liquidity problems. Despite the scheme, which included effectively borrowing millions of dollars from vendors by initiating a program of delayed payments and false statements in SEC filings about the liquidity of the company, Kmart eventually collapsed in bankruptcy. A jury found the defendant liable for violations of Exchange Act Section 10(b) among other things. See also SEC v. Morrice, Civil Action No. CV 09-01426 (C.D. Cal. Filed Dec. 7, 2009) (fraud action against the former senior officers of subprime lender New Century Financial settled in February 2011 in part by consents to injunctions based on the anti-fraud provisions as discussed earlier in this series). --By Thomas O. Gorman, Dorsey & Whitney LLP Tom Gorman is a partner in Dorsey & Whitney's Washington, D.C., office. He is co-chairman of the American Bar Association's white collar, securities fraud subcommittee. He is also the author of a blog which analyzes trends in SEC enforcement. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the firm, its clients, or Portfolio Media, publisher of Law360. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. All Content © 2003-2011, Portfolio Media, Inc.