QUALITY MANAGEMENT IN HIGHER EDUCATION 3.2 THE

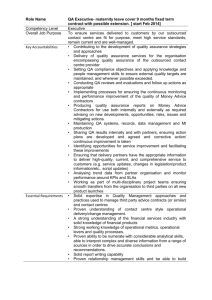

advertisement