Hot Issues in Patenting Antibodies

advertisement

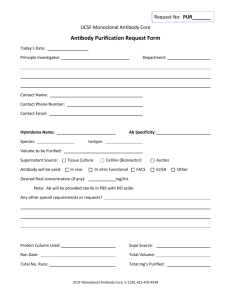

Hot Issues in Patenting Antibodies 6th Annual Antibody Therapeutics Conference IBC Life Sciences San Diego, CA December 9-11, 2008 Moderator: Timothy J. Shea, Jr. – Director Sterne, Kessler, Goldstein & Fox P.L.L.C. Panelists: Michael Braunagel, Ph.D., Director, Strategic Alliances and Licensing, Affitech AS Diana Hamlet-Cox, Ph.D., J.D., Vice President and Chief Patent Counsel, Medarex, Inc. Bernd Hutter, Ph.D., Associate Director & Team Leader IP, MorphoSys AG Diane Wilcock, Ph.D., Director, Intellectual Property, Xoma (US) LLC; Jennifer A. Zarutskie, Ph.D., J.D., Director of Intellectual Property, Patent Counsel, Dyax Corp. Introduction • Therapeutic antibodies have come of age • Fastest-growing segment of pharmaceutical industry – Growing at rate of 30% per year • 2007 revenues of approximately $26 billion • Five of the six biopharma R&D collaborations valued at >$1B in 2007 focused on antibody technologies • As antibody technology as evolved, so has the legal landscape • Strategies for patenting pioneering antibody technologies of yesterday are not necessarily applicable today 2 Introduction • Our panel of experienced in-house IP experts will address four hot topics in antibody patenting: – Patentability issues • Obviousness after KSR • Written description/enablement – Freedom-to-Operate issues – Antibodies as biosimilars – Patent life-cycle management 3 Patentability Issues - Basics • Antibodies must meet same standards for patentability as other inventions: – Antibody must be novel • i.e., not disclosed in single prior art reference – Antibody must be nonobvious • i.e., cannot be obvious modification of what is already publicly known in field – Application must describe antibody with sufficient specificity • Enough to show that inventors had “possession” of full scope of what is claimed as invention – Application must enable how to make and use antibody – Application must teach best mode known to inventors of making/using invention (US only) • Nonobviousness and written description have become the most difficult hurdles in antibody patenting 4 Patentability Issues - Obviousness • The bar for showing that an antibody is nonobvious has been raised in the U.S. – Now closer to EP standard (inventive step) • KSR Int’l v. Teleflex Inc. (S. Ct. 2007) – Rejected “rigid approach” of Fed. Cir. (i.e. TSM test) as inconsistent with more “expansive and flexible” analysis set forth in S. Ct. precedent – “The combination of familiar elements according to known methods is likely to be obvious when it does no more than yield predictable results” – “obvious to try” may be enough (in some cases) – Made easier for examiners to shift burden to applicant to show invention not obvious 5 Patentability Issues - Obviousness • Ex parte Kubin (BPAI 2007) – Decided one month after KSR – Currently on appeal to Fed. Cir. – Calls into question Fed. Cir. ruling in In re Deuel • But cannot overrule since Board decision – Deuel (Fed. Cir. 1995) • Claims to sequence for gene not prima facie obvious over prior art teaching of method of gene cloning, together with reference disclosing partial amino acid sequence for protein even where motivation to obtain sequence existed • “Obvious to try” not standard • Applied chemical standard for structural obviousness – Kubin • Board cited KSR for proposition that “obvious to try” can be enough to establish prima facie case • Cited advances in state of art since Deuel • Affirmed rejection – Motivation to sequence existed – Methodologies available – Reasonable expectation of achieving success 6 Patentability Issues – Obviousness • PTO Training Guidelines – Issued post-KSR – Set forth acceptable “rationales” to support rejection – Rationale D (particularly applicable to antibody technologies)– • Applying a known technique to a known product ready for improvement to yield predictable results • Dilemma – Many of pioneering antibody technologies have become mainstream • • • • Humanization Phage display Transgenic mice Fc engineering? 7 Patentability Issues - Obviousness • Hypothetical I – Mouse antibody A to human antigen X was known. Company took A, humanized it to produce AJ then engineered the Fc region to produce AK which has dramatically increased effector function (e.g., ADCC). General techniques for humanizing and Fc engineering are known in art. Ab claimed in terms of VH and VL sequences, which are novel. – Obvious??? 8 Patentability Issues - Obviousness • Hypothetical II – Full-length human antigen “X” has been characterized and is known to be a receptor for an apoptotic pathway. Company used phage display to generate novel Ab “A.” Epitope mapping shows A is first Ab known to bind particular epitope. In vitro assays show Ab is agonistic and induces apoptosis in target cells. Claimed in terms of CDR sequences, epitope and function. – Obvious??? 9 Patentability Issues - Obviousness • Ways to Defeat Obviousness Rejections Generally – Show no reasonable expectation of success to produce claimed antibody/method of use (i.e. not predictable) – Show claimed antibody/method of use has unexpected results • Anticipating the rejection (Filing Strategies) – Counsel and scientists must work together to characterize Abs as much as possible before filing (Must be interactive) • Epitope mapping • Functional properties – Include in vivo data as early as possible – Follow up with clinical observations (often unpredictable) – Benchmark your Ab against prior art Abs to identify superior features • Rebutting the rejection (Prosecution Strategies) – Work with scientists to design experiments to include in expert declarations 10 Recently Granted US Antibody Patents 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% Novel Ag Ab Seqlimited Hybma Epitope Diag Function Other Type US patents granted from 1 Aug – 1 Nov 2008 with “antibod*” in title. N=120 11 Examples Of Recently Granted Epitope Claims • An isolated monoclonal antibody specific to CYP24 wherein the antibody binds specifically to the CYP24 epitope C-QRLEIKPWKAYRDYRKE-NH2 (SEQ. ID. NO. 2). • A method of making an antibody that specifically binds to cytochrome P450 CYP1B1, the method comprising raising the antibody using a peptide consisting of an amino acid sequence ….. or an antigenic fragment thereof. • A monoclonal anti-CD80 antibody or CD80-binding fragment thereof, wherein the antibody has the same epitopic specificity as an antibody selected from the group consisting of: ….. 12 Examples Of Recently Granted Functional Claims • An isolated human antibody or antigen binding fragment thereof that specifically binds properdin, wherein said antibody inhibits oligomerization of a properdin monomer. • A host cell expressing a monoclonal antibody or fragment thereof that binds specifically to human CD80 antigen and inhibits the binding of the CD80 antigen to CD28 without inhibiting the binding of the CD80 antigen to CTLA-4. • A method of treating rheumatoid arthritis in a human comprising administering to the human an effective TNFT-inhibiting amount of an anti-TNFT antibody or antigen-binding fragment thereof, said antibody comprising a human constant region, wherein said antibody or antigen-binding fragment (i) competitively inhibits binding of A2 (ATCC Accession No. PTA-7045) to human tumor necrosis factor TNFT, and (ii) binds to human TNFT with an affinity of at least 1×108 liter/mole, measured as an association constant (Ka). 13 Patentability Issues – Written Description/ Enablement • Written description – application must show applicant has “possession” of full scope of invention claimed – WD has become primary battleground in Ab patenting (and biotech patenting generally) • Genus claim vs. species claim – Species claim protects specific Ab • E.g. Ab claimed in terms of specific VH and VL sequences • Generally easier to design around – Since changes to sequence can take outside of scope of claim (assuming not “equivalent”) – Genus claim protects specific Ab and others with like structure and/or function • E.g., Ab claimed in terms of epitope it binds to and function • Generally more desirable since much broader and therefore more difficult to design around 14 Patentability Issues – Written Description/ Enablement • • Issue: What is required in application to support generic or subgeneric claims? Rule: – “A genus can be described by disclosing: (1) a representative number of species in that genus; OR (2) its ‘relevant identifying characteristics,’ such as ‘ complete or partial structure, other physical and/or chemical properties, functional characteristics when coupled with a known or disclosed correlation between function and structure, or some combination of such characteristics.” In re Alonso (Fed. Cir. October 30, 2008) – Alonso • Generic claim to method of treating neurofibrosarcoma in a human by administering a therapeutically effective amount of a mAb idiotypic to the neurofibrosarcoma (not lim. to spec. mAb) • Application disclosed one mAb • Court found one mAb not representative of “densely populated genus” • “The specification teaches nothing about the structure, epitope characterization, binding affinity, specificity, or pharmacological properties common to the large family of antibodies implicated by the method.” 15 Patentability Issues – Written Description/ Enablement • Broad generic claims are possible – If first to fully characterize a novel antigen (Noelle claim) • E.g., “An antibody that specifically binds antigen X.” • But truly novel antigens increasingly rare • Subgenus claims (the battleground) – Structure-function correlation is key • But how much??? – What is “representative number of species”? – Do you need all CDRs described? VH and VL? Is VH CDR3 enough? Can the “structure” come from the antigen (e.g., epitope?) – What is needed to show function? Is in vivo data needed? 16 Patentability Issues – Written Description/ Enablement • Novel Antigens: Still A Low Threshold For Broad Antibody Claims • Broad claims are still being granted for antibodies to novel targets even where no antibody was actually made. • For example US 7,442,772 – Granted October 2008 – Claim 1. An isolated antibody that binds to the polypeptide shown in FIG. 32 (SEQ ID NO:83) – Made functional predictions based on homology – Provided prophetic examples 17 Sequence-Limited Claims; Recent Examples • V regions – An immunologically active chimeric anti-CD20 antibody, wherein the antibody comprises a light chain variable region comprising the amino acid sequence shown as residues 23 to 128 of SEQ ID NO: 4 and a heavy chain variable region comprising the amino acid sequence shown as residues 20 to 140 of SEQ ID NO: 6 • 6 CDRs – A purified polynucleotide which encodes a human antibody, wherein the antibody comprises: • a VHCDR1 region comprising an amino acid sequence as set forth in SEQ ID NO:355; • a VHCDR2 region comprising an amino acid sequence…; • a VHCDR3 region comprising an amino acid sequence…; • a VLCDR1 region comprising an amino acid sequence…; • a VLCDR2 region comprising an amino acid sequence…; and • a VLCDR3 region comprising an amino acid sequence…. • <6 CDRs – An isolated human antibody or a fragment thereof, which comprises at least three complementarity determining regions (CDRs), wherein one of the at least three CDRs has the sequence of SEQ ID NO:51 and which antibody or fragment thereof specifically binds to an aspartyl (asparaginyl) X-hydroxylase (AAH). 18 Patentability Issues – Written Description/ Enablement • Anticipating the rejection – Application should provide as many exemplary Abs in genus as possible • Extra support for commercially relevant leads – Include information about the target and target-Ab interaction • Alonso: epitope characterization, binding affinity, specificity, pharmacological properties, etc. • Data linking structure and function can be valuable for increasing claim scope – Identify those antibody residues key for functional activity 19 Patentability Issues – Written Description/ Enablement • Enablement (how to make and use) – Generally easier for application to teach how to make and use full scope of invention than to show actually had possession at filing • Anomaly – possible for application to adequately teach how to make and use claimed genus, but not adequately describe it – Key distinction from WD • In US, Applicants can use data generated after the filing date to show application enables claim – But more difficult in EP and JP – Do not need to enable later arising technology, but “nascent technology” requires “specific and useful” teaching to enable (Chiron v. Genentech (Fed. Cir. 2004) 20 Patentability Issues – The European Perspective • Difficult to get claims to Ab if another Ab with similar properties was known – Your Ab must have different (preferably superior) features • Making an Ab against a known target is not innovative per se • Generic Ab claims – new gene – If gene novel and some relevant function determined, can often get one patent to gene, polypeptide and Ab to same • Ab claims to known polypeptides – EPO will require substantial disclosure of Ab structure, function, properties, etc. – Some indication of inventiveness required (e.g., higher affinity, binding to key epitope, special function, etc.) – Tendency by EPO to limit to specific CDRs • Even where invention was more directed to function 21 Patentability Issues – The European Perspective • Other key differences EP vs. US – First-to-file (EP) vs. first to invent (US) – Grace period (US) vs. absolute novelty (EP) – Opposition (EP) vs. Reexamination (US) – Best mode in US, not in Europe – IDS requirement in U.S., not in Europe 22 FTO Fundamentals • Patentability Z freedom to operate (FTO) – Patent is only a grant of the right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the patented invention – Patent does not give patent owner the affirmative right to do anything • No affirmative right to make, use, sell own invention – KEY: A company can receive a patent for its technology and still be blocked from practicing that technology by a broader (dominant) patent 23 FTO Fundamentals • Dominant patents vs. subordinate patents – Example: • Company A may receive a patent to a specific anti-CD20 humanized antibody, but may be blocked from making, using or selling that antibody by Company B’s patent to basic humanization technology and Company C’s patent broadly directed to any recombinant antibody that binds CD20. – Holder of subordinate patent may need license under each dominant patent to practice its own technology! 24 FTO Fundamentals • BUT – subordinate patent can still have value – If subordinate patent is directed to improvement in the technology that is considered essential or particularly advantageous • Example: PDL’s Queen patents on humanization technology • Valuable subordinate/improvement patent can be tool to clear FTO (e.g., through cross-license) 25 The FTO Search • Focus is on what is claimed, not just what is disclosed in application – Claims often much broader (c.f. Alonso) • Best to search issued patents and published applications – Published applications show what is coming and can give rise to provisional rights • Caveats – No guarantee that all relevant patents will be identified • Delay in U.S. between filing and publication • Some applications never publish before issuance – No guarantee that pending applications will issue with published claims • Often filed with extremely broad claims that have little chance of issuing • Moving target 26 Strategies for Clearing FTO • Noninfringement/Design Around Analysis – Determine whether claims actually cover contemplated commercialization activity – Consider alternatives that will avoid claims (i.e., “design around”) – Carefully review prosecution history • Prosecution history can be roadmap to design-around strategies – Limitation on doctrine of equivalents (Festo) • Invalidity Analysis – Consider whether claims anticipated by or obvious over prior art • Broad claims more difficult to obtain now (but not impossible – see Noelle) – Consider whether claimed subject matter adequately described and enabled • As discussed above, important considerations for Ab technologies 27 Strategies for Clearing FTO • Practical Analysis – What is stage of your technology? Will patent be expired by time you go to market? – While older targets may have better FTO, your own patent protection is likely to be narrower – Impact of Seagate (Fed. Cir. 2007) • Eased affirmative duty of potential infringers to exercise due care • Opinions of counsel not per se required, but authoritative, outside opinion still valued by inhouse counsel • Increased value in proactive FTO analyses 28 Strategies for Clearing FTO • Consider applicability of FDA Safe Harbor Exemption (35 U.S.C. 271(e)(1)) – European equivalent is “Bolar exemption” – U.S. statute exempts from infringement uses of patented inventions for purposes reasonably related to generating information for FDA approval – Merck case (US Supreme Court) construed exemption very broadly – Impact on research tools in Ab space? • Recently Fed. Cir. placed limits on exemption in Proveris – Found defendant’s optical spray analyzer used by customers to generate data on drugs for FDA submissions infringed claims to system and method for characterizing aerosol sprays – Exemption not available where OSA itself not subject to premarket approval and defendant not seeking FDA approval • Question: What does this mean for Ab discovery technologies such as phage display and transgenic mice? • Question: How will courts analyze an antigen claim under this analysis? – Antigen could hypothetically be a drug itself, but likely isn’t. When is that determination made? 29 Strategies for Clearing FTO • Reexamination (hot area) – Faster and much less costly than litigation • Similar to oppositions in Europe – Limited to patents and publications – Must have “substantial new question of patentability” • Easier to show in view of KSR – Easier burden of proof compared to litigation – >90% of reexam requests are granted by PTO – >70% of reexams – claims canceled or changed • can extinguish past damages if in litigation – Notable Ab reexam – Cabilly II (Genentech) – Claims finally rejected (decision on appeal) 30 Strategies for Clearing FTO • Licensing – Consider whether taking license is desirable/possible • Particularly if noninfringement/design around/invalidity positions uncertain – License more likely to be granted where patent holder is not competitor and does not plan to exploit technology in your intended field of use – BUT – must keep in mind royalty stacking problem (particularly in antibody space) • Allow for need for possible licenses in future 31 Strategies for Clearing FTO • Licensing – Antibody Humanization • Winter patents • Queen patents – Phage Display industry – Example of where subordinate patent is as valuable or more valuable than dominant patent 32 Strategies for Clearing FTO • Offshoring – Must consider 35 U.S.C. 271(g) • Importation of product made abroad by process patented in US can be infringing even where no patent in country where product made – But see Kinik • 271(g) defenses not available in ITC exclusionary actions! 33 Patent Life Cycle Management for Abs • The Dilemma – The cost to develop a drug or biologic and it bring to market is hundreds of millions of $$$ – Patent protection for the basic NCE or protein is generally sought very early in the R&D process – Due to the extensive regulatory review period, significant patent term has been lost by the time the product goes to market – Traditional NCE strategies may not be available and claims may be harder to get given that Abs are single class of structurally similar molecules 34 Patent Life Cycle Management for Abs • Strategic use of patents to maintain product exclusivity and revenue stream over life of blockbuster drug or biologic • Involves obtaining additional patents that extend protection beyond the original patents covering the NCE or biologic per se 35 Patent Life Cycle Management for Abs • Strategies – Develop/access newly patented platforms • to make second generation products (e.g. improved ADCC, half-life, etc.) – Manage filings • To limit extent to which own earlier filings limit ability to protect later innovations • Multiple provisional filings in US within priority year are not uncommon – Consider filing on clinical applications • Disease specific • Route of admin., pharm. Formulations, timing and sequence of coadmin. Therapies • Mechanisms? – What to keep as trade secrets? 36 Antibodies as Biosimilars • Biosimilar Legislation is Coming in US – No longer a matter of if, but when – Proposed legislation is stalled but will regain momentum with new administration • Competition likely to come from big pharma/large biotechs as much as usual generics – experience with clinical trials will be key advantage • But is development of biosimilar mAbs even possible with current technology? – Pros: • structure, and safety and efficacy profiles generally well established, readily available potency assays – Cons: • small structural changes can have major functional significance, efficacy and safety highly specific • Myozyme – same manufacturer needs FDA approval to add second plant to make same exact product (Genzyme need separate BLA.) 37 Antibodies as Biosimilars • What will framework look like? – Very different from ANDAs – Some clinical trials will likely be required – FDA will look to EMEA for guidance • Develop regulatory framework cautiously – Biosimilarity Z interchangeability • Interchangeability is the “holy grail” since would allow doctor to substitute biosimilar for brand – but FDA says technology not there yet for Abs • Most biosimilars will be follow-ons, but not truly interchangeable 38 Antibodies as Biosimilars • BLA for Biosimilar Requirements (House bill) – Applicant must demonstrate that: • Product is “biosimilar” to a reference product • Product and reference product utilize the same mechanism of action for the condition of use • Condition of use has been previously approved for reference product • Route of administration, dosage form and strength are same as reference product • Facility meets standards to assure safety, purity and potency – Data exclusivity is key battleground • BIO advocates 14 years • To extent possible, avoid limiting value of regulatory data protection by disclosing too many details about how to make/test product 39 Antibodies as Biosimilars • European perspective – “Similar biological medicinal products” – Legal framework exists; regulatory framework is developing – “biosimilars” approved to date by EMEA • Omnitrope (Sandoz)(2006)(first biosimilar approved by EMEA) • Valtropin (Biopartners)(2006) • Binocrit (Sandoz)(2007) • Epoetin alfa (Hexal)(2007) • Abseamed (Medice Arzneimittel Pütter)(2007) 40 Antibodies as Biosimilars • EMEA Core Principles – Biological medicinal products are much more difficult to characterize than small molecules • Broad spectrum of complexity across biological products – standard generic approach for small molecules is “scientifically not appropriate” for biologicals – Patient safety is paramount – Case-by-case basis and dictated by the science – The toxological and clinical profile of the biosimilar “shall be provided” – A well-defined regulatory framework can only be developed over time based on experience and increased scientific knowledge – Patients and physicians must be informed in the event of the substitution of an original product by a similar biological product 41 Hot Topics in Patenting Antibodies Thank You 42