Arts Good Study Guide - Open University Worldwide

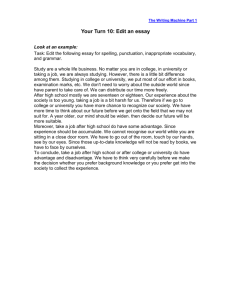

advertisement