Clinical Case Management Resources

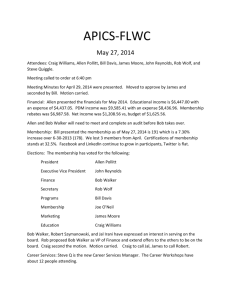

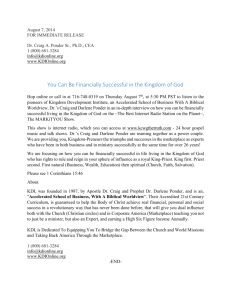

advertisement