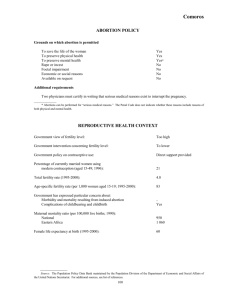

Unburdening the Undue Burden Standard: Orienting "Casey" in

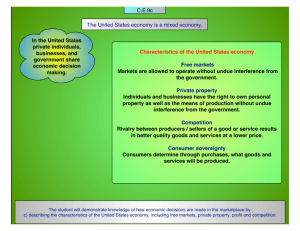

advertisement