Ch 12 - Introduction to Strategic Leadership

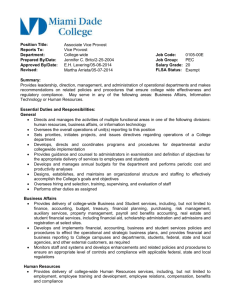

advertisement