Kobe Chang 49702032

advertisement

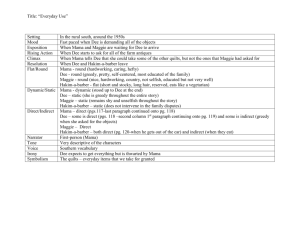

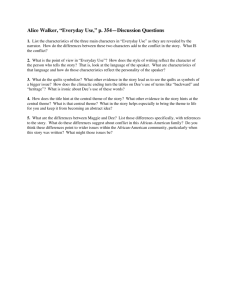

Chiu 1 Conflicts within the Black Pride Movement in Alice Walker’s “Everyday Use” Jane Chiu (丘家甄) Alice Walker is a famous African American author, poet, activist, and the Pulitzer Prize winning novelist for her acclaimed novel, The Color Purple. Walker has produced many kinds of works dealing with gender and racial issues. Her writings depict the struggles of black people, especially black women and their lives in a sexist and racist society. During her college life in the early 1960s, Walker decided to go back to the south of America as an activist for the Civil Rights Movement. Later, the Black Pride Movement grew out of the Civil Rights Movement during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The message of the Black Pride Movement is that black people should be proud of being black. Moreover, it encouraged African Americans to recognize their culture and heritage. Walker ’s short story “Everyday Use” discusses different positions within the Black Pride Movement. The narrator of the story Mama is an African American woman who has two daughters, Dee and Maggie. The story begins with Mama and Maggie waiting for Dee’s arrival from the north. Then Mama starts to recall Dee’s personality and describes the differences of her two daughters. After Dee comes home, she demands many supplies in the house, especially the quilts. Therefore, a conflict occurs between Dee and Maggie regarding the entitlement to the quilts. Finally, Mama has an epiphany that Maggie is the right person who is entitled to have the quilts. At first glance, the short story seems to simply describe the different personalities of Mama, Maggie, and Dee and to recount the tensional event of the entitlement to the quilts; however, a deeper analysis reveals that Walker illustrates more than this. She asks readers to rethink the effects of the Black Pride Movement on African Americans and the debates and conflicts within the movement itself regarding issues of identities, heritage, and different dimensions of African American culture. In “Everyday Use,” Mama is the narrator and her characteristics are shown in the Chiu 2 relationships with her two daughters. Mama is a “large,” “big-boned” black woman with “rough,” “man-working hands” (109). Also, Mama thinks that her “fat” can keep her warm in winter. In addition, she can be a butcher just like a man and work outside all day long to earn a living. Therefore, Mama is like the head of the rural homestead by her physical strength and farming knowledge. However, she is somehow dissatisfied with her physical appearance. For example, Mama sometimes dreams that she attends “a TV program” (109) with Dee in a different image. She should lighten her weight “a hundred pounds” (109) and whiten her skin color like “an uncooked barley pancake” (109). Her black look in real life is the contrast to the images promoted by the white society. As Susan Farrell points out, “Mama has a rather troubled relationship with her older daughter” (179). Thus, through Mama’s recurring dreams, we can see that she wants to be like “her daughter would want [her] to be” (109). In addition, Mama never has an education at that time. In spite of Mama’s efforts to raise her two daughters and her abilities as a man, her low education, limited job opportunities, and less attractive appearance force her to have poor self-image under the racist society. On the other hand, Mama describes and treats Maggie and Dee in different ways. For instance, their skin color and hair are quite different. “Dee is lighter than Maggie, with nicer hair and a fuller figure” (110): this line indicates that Dee has a better figure in the black community for they consider that light-skinned black people are more beautiful than darker skinned black Americans. What is more, Mama seems to project a version of herself onto each daughter. Mama keeps Maggie by her side and they are similar to each other in some way like they all have unappealing appearance and darker skin. And Mama appears that she does not cultivate Maggie attentively. However, Dee has many advantages to facilitate her to strive upward to a higher social status. Due to the superior conditions of Dee, Mama gives her full attention, sends her to school, and takes pride in her. It reveals that Mama also wants to have a positive self-image approved by the mainstream society and she desires Dee to accomplish it. As a Chiu 3 matter of fact, Mama has her projections onto her two daughters. From Maggie’s body language and her interactions with Mama, Dee, and Dee’s boyfriend Asalamalakim, readers can know that Maggie suffers from low self-esteem. For example, Maggie is like a tame and diffidence animal. Mama describes Maggie, as “a lame animal” (110), walks with “chin on chest, eyes on ground, [and] feet in shuffle” (110). Many years ago, the terrible house fire made Maggie’s body injured and now she has burned scars on her limbs. In addition, according to Mama’s description, Maggie has darker skin and she does not have her sister’s “nicer hair” and “fuller figure” (110). Also, Maggie is ashamed of the “burn scars” (109) on her arms and legs and always views Dee with “a mixture of envy and awe” (109). Thus, Maggie feels inferior to her sister in many ways and she is lack of confidence. Maggie has an intimate relationship with Mama. Mama and Maggie stay together in the south and both of them do not receive good education. Although Maggie sometimes would read to Mama, she still “stumbles” and “can’t see well” (110). Maggie knows “she is not bright” (110) and her mother also considers that Maggie is not possessed of “good looks and money” (110). If Dee arrives at their home, Mama supposes that Maggie will be “nervous” and will “stand hopelessly in the corners” (109). As John Gruesser writes in his essay, “Mama frequently describes Maggie as a docile, somewhat frightened animal, one that accepts the hand that fate has dealt her and attempts to flee any situation posing a potential threat” (183). After Dee’s arrival, Maggie attempts to rush back to their house; however, Mama asks her out and Maggie is nervous for she “tries to dig a well in the sand with her toe” and “[cowers] behind [Mama]” (111). As Maggie sees Dee’s boyfriend (or husband), she trembles and sweats like a pig and her hands are as cold and limp as a fish. Over all, “Maggie is the aggregate underclass,” writes David Cowart, “that has been left behind as a handful of Wangeros [Dee] achieve their independence—an underclass scarred in the collective disasters Walker symbolizes neatly in the burning of the original Johnson home” (173). Chiu 4 As for Dee, she is imperious, audacious, and self-centered. For instance, Maggie “thinks her sister has held life always in the palm of one hand, that ‘no’ is a word the world never learned to say to her” (109). Also, Mama mentions that Dee “would always look anyone in the eye” and “hesitation was no part of her nature” (109). Readers can recognize that Dee is good at handling things and is ambitious and confident to show her abilities. In addition, Dee’s skin color is lighter and the texture of her hair and the type of her body is closer to white standards of beauty. That is, Dee’s attractive appearance can be considered superior by mainstream American society and she can much easier and successfully move up in the world than other black people. Dee takes advantage of her intelligence and education to oppress Mama and Maggie. The following passage of Mama’s description will make this point clear: “She used to read to us without pity; forcing words, lies, other folks’ habits, whole lives upon us two, sitting trapped and ignorant underneath her voice. She washed us in a river of make-believe, burned us with a lot of knowledge we didn’t necessarily need to know. Pressed us to her with the serious way she read, to shove us away at just the moment, like dimwits, we seemed about to understand” (110). Dee shows off her superior attitude toward Maggie and Mama; for her, they are like “dimwits” (110). Though Dee is highly educated, she takes advantage of her intelligence and aptitude and look down upon her mother and sister. As for fashion style and taste, Dee has a high opinion of her self and is proud of her sophistication and elegance. Mama once dreamed that Dee pinned on her dress “a large orchid” (109) when she attended a TV program. However, Dee has told Mama once that she thinks “orchids are tacky flowers” (109). As it is stated by Susan Farrell, “Dee is concerned with style, but she’ll do whatever is necessary to improve her circumstances. For instance, when Dee wants a new dress, she ‘makes over’ an old green suit someone had given her mother. Rather than passively accept her lot, as Mama Chiu 5 seems trained to do, Dee ‘was determined to stare down any disaster in her efforts.’” Also, Mama claims that Dee wants “nice things” and “at sixteen she had a style of her own; and knew what style was” (110). Readers can know Dee’s style is closer to white people’s lifestyle and taste. However, when Dee becomes adult and is influenced by the Black Pride Movement, she also wants to be fashionable to be proud of her origins. When Dee arrives at home, her dressing and accessories are like folk style and bohemia style. She wears long “loose dress” that flows down to the ground and her “earrings” and “bracelets” are “dangling” and “making noises” (111). Now, Dee is a successful woman living on her own, has achieved financial success and had a high social status. However, her success or advances can be said to be defined by its dismissal of her less white and much poorer community. A past that continues to haunt Dee even though she tries hard to break her ties with it. In Walker’s “Everyday Use,” the three main characters all endeavor to resist internalized racism; however, in the wake of Black Pride Movement, Mama, Maggie, and Dee have different attitudes toward their names, heritage, and roots. Mama is nostalgic and she takes pride in herself and in her heritage. When waiting for her first-born daughter’s coming, Mama sweeps and cleans up the yard and she thinks the yard is “like an extended living room” (109). In Mama’s mind, the yard is a vital part of the house and it belongs to their daily life. After Dee arrives at home, her first reaction is to take photos immediately. Dee takes out “a Polaroid” (111) and stoops down to take a picture of Mama and Maggie sitting in front of their house like a tourist. In the past she never brings her friends to her house because she feels ashamed about her family and looks down on her roots. After studying in the north, Dee looks her roots in white people’s eyesight and she even changes her name to “Wangero” (112). “I couldn’t bear it any longer, being named after the people who oppress me” (112), said Dee. She associates her heritage with poverty, racial discrimination, and the enslavement of her ancestors. Thus, she has tried to be different from her family throughout her life. Chiu 6 However, the name is given by Mama. She tells Dee about the source of the name and we learn that it is from her sister and Grandma Dee. Mama is able to trace back the name to the previous generations of her family and knows about her family history. In contrast to Mama’s slow and dull tongue, Wangero “talks a blue streak” (112). Everything in the house all “delights her” (112). After noting “the benches,” “Grandma Dee’s butter dish,” “the churn,” “and the dasher” (112), Wangero wants to collect them all in order to decorate her deluxe mansion. Wangero associates the hand-made articles for daily use with collections; however, these hand-made supplies have a sense of touch and have their own stories and all objects are made for using and each of them is very different and unique. So far as Mama is concerned, she does not have to “look close to see where hands pushing the dasher,” she can easily feel the dasher that “had left a kind of sink in the wood” (113). Cowart once again notes that Dee “wants, in short, to do what white people do with the cunning and quaint implements and products of the past” (175). After finishing dinner, Dee starts “rifling” (113) in Mama’s room. There are “two quilts”; one is “the Lone Star pattern,” and the other is “Walk Around the Mountain” (113). Every piece of the quilts is made from their ancestors’ clothes. Dee covets the two quilts too; however, Mama has decided to give them to Maggie. Dee is wayward and does not want other quilts that “are stitched around the borders by machine” (113). Ironically, Dee can distinguish objects that are made by hands and by machine. In addition, Mama once gave Dee a quilt when she went away to college but she thought that quilts were “old-fashioned” and “out of style” (115). As Mama claims that the quilts are Maggie’s, “Maggie can’t appreciate these quilts!” Dee says, “She’d probably be backward enough to put them to everyday use” (115). Also, Dee just wants to “hang them” (115) in her house. In fact, as David Cowart says in his essay, “the quilts remain appropriate for ‘everyday use’ so long as the art of their manufacture remains alive” (180). Maggie is shocked at first and then she is composed. Maggie, “like somebody used to never winning anything, or having Chiu 7 anything reserved for her,” says, “she can have them, Mama, I can ’member Grandma Dee without the quilts ” (115). Maggie has the knowledge of her family history and takes pride in her heritage. She even knows how to quilt and keeps the quilts working in their daily life. As it is stated by John Gruesser, “Mama has her epiphany, realizing that her thin, scarred, pathetic daughter, who knows how to quilt and serves as her family's oral historian, deserves the quilts more than her shapely, favored, educated daughter Dee, who only wants the quilts because they are now fashionable” (184). Thus, Mama does something she has never done before: she refuses Dee’s requests and gives Maggie what she wants. As Gruesser once again notes, “significantly, in seeing the value in Maggie, Mama has been able to look beneath the surface of things and see the value in herself as well” (185). However, Dee still reckons she is right and they do not understand their “heritage” (115). Then, Dee puts on her “sunglasses” (115), gets in the car, and returns to her home in the north. The “sunglasses” somehow represent Dee’s social status and also imply that she cannot see things well. Mama and Maggie both embrace their heirlooms and culture; on the other hand, Dee just wants to demonstrate her high social status and great sense of fashion. To quote David Cowart again, “Wangero claims to value heritage, and Walker is surely sympathetic to someone who seems to recognize, however clumsily, the need to preserve the often fragile artifacts of the African American past” (175). Though Dee is seeking for a sense of self-worth in African culture and heritage, her responses to the Black Pride Movement seems to make her become a superficial and shallow person who desires to fit into a new fashionable world. As for Dee’s ideas of names, “she is confused and has only superficial knowledge of Africa and all it stands for” (38), said by Helga Hoel. In addition, as Cowart suggests that, “in her name, her clothes, her hair, her sunglasses, her patronizing speech, and her black Muslim companion, Wangero proclaims a deplorable degree of alienation from her rural origins and family” (172). As we have seen, Walker’s “Everyday Use” is not just a simple short story about a Chiu 8 mother and her two daughters having a quarrel about their heirloom. It is in fact a great piece of literary work that has many layers of meanings and profound ideas. By analyzing Mama, Maggie, and Dee’s personalities and interactions, I have shown how complicated and difficult the situation is for black women struggling in a racist society. Internalized racism is an evil disease that plagues all characters in the story. Besides, Walker’s story is about the Black Pride Movement and black people’s different stances toward the Movement. She urges African Americans to rethink the meanings and sources of black pride in the history of Africans in America and points out the importance of family tradition, folk heritage, and community in surviving the harsh realities of racism. Chiu 9 Works Cited Cowart, David. “Heritage and Deracination in Walker’s 'Everyday Use.'.” Studies in Short Fiction 33.2 (Spring 1996): 171-184. Rpt. in Short Story Criticism. Ed. Jelena O. Krstovic. Vol. 97. Detroit: Gale, 2007. Literature Resource Center. Web. 2 Jan. 2013. Farrell, Susan. “Fight vs. Flight: A Re-Evaluation of Dee in Alice Walker’s ‘Everyday Use.’.” Studies in Short Fiction 35.2 (Spring 1998): 179-186. Rpt. in Short Story Criticism. Ed. Jelena O. Krstovic. Vol. 97. Detroit: Gale, 2007. Literature Resource Center. Web. 2 Jan. 2013. Gruesser, John. “Walker’s ‘Everyday Use.’.” Explicator 61.3 (Spring 2003): 183-185. Rpt. in Short Story Criticism. Ed. Jelena O. Krstovic. Vol. 97. Detroit: Gale, 2007. Literature Resource Center. Web. 2 Jan. 2013. Hoel, Helga. “Personal Names and Heritage: Alice Walker’s ‘Everyday Use.’.” American Studies in Scandinavia 31.1 (1999): 34-42. Rpt. in Short Story Criticism. Ed. Jelena O. Krstovic. Vol. 97. Detroit: Gale, 2007. Literature Resource Center. Web. 2 Jan. 2013. Walker, Alice. “Everyday Use.” An Introduction to Literature: fiction, poetry, and drama. Ed. Barnet, Sylvan, William Burto, and William E. Cain. 15th ed. New York: Longman, 2008. 109-15.