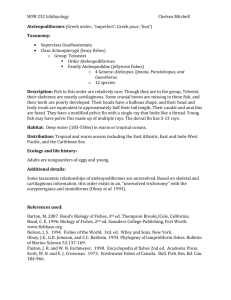

Diversity and Phylogeny of Neotropical Electric Fishes

advertisement