Language, Region and Community - Anveshi – Research Centre for

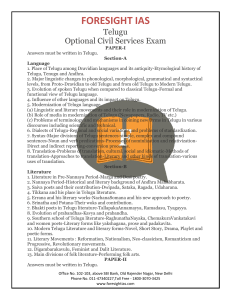

advertisement