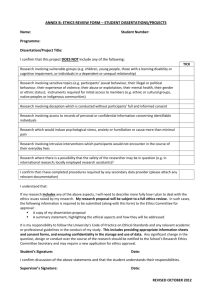

introduction 1. ethical responsibilites

advertisement