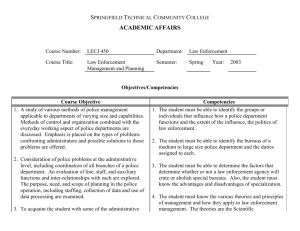

Meeting Law Enforcement's Responsibilities

advertisement