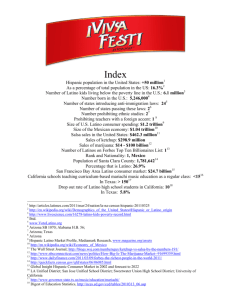

Why Some Schools With Latino Children ...and Others Don'tdo

advertisement