A History of The Coca-‐Cola Company and Its

advertisement

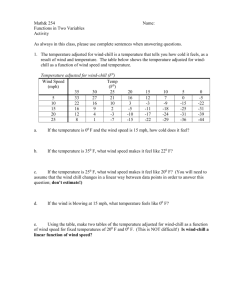

A History of The Coca-­‐Cola Company and Its World War II Public Relations Campaign Marianne McGoldrick JMC 68009 Professor Sledzik February 23, 2014 1 Abstract Author Peter N. Stearns says, “Only through studying history can we grasp how things change; only through history can we begin to comprehend the factors that cause change; and only through history can we understand what elements of an institution or society persist despite change.” Through the examination of the history of The Coca-­‐Cola Company, it can be deduced that the organization’s World War II public relations campaign catapulted the business to global brand success. This paper will explore the various campaign factors that changed The Coca-­‐Cola Company’s business outlook from one that was primarily domestic to one of international proportions, including powerful advertising and the unique creation of pop-­‐up bottling systems in 64 countries. The examination will illustrate Stearns’ statement that only through studying history can we grasp how and why things change. 2 Introduction The Coca-­‐Cola Company is the world’s largest beverage company, with an operational reach that encompasses over 200 countries and delivers happiness at over 23 million outlets worldwide.iii The corporation has come a long way since their modest beginning in 1886 in Atlanta, Ga. In the first year, Coca-­‐Cola creator John Pemberton sold an average of nine servings of the beverage each day. Today, that number has increased to over 1.8 billion.iii This raises the question: How did Coca-­‐Cola become the global brand it is today? Author Peter N. Stearns says, “Only through studying history can we grasp how things change; only through history can we begin to comprehend the factors that cause change; and only through history can we understand what elements of an institution or society persist despite change.”iv Through the examination of the history of The Coca-­‐Cola Company, it can be deduced that the organization’s World War II public relations (PR) campaign catapulted the business to global brand success. Ragan’s PR daily identifies the company’s World War II campaign as one of the most important in history.v This paper will explore the various campaign factors that changed The Coca-­‐Cola Company’s business outlook from one that was primarily domestic to one of international proportions, including the powerful “The Global High Sign” advertising campaign and the unique creation of pop-­‐up bottling systems in 64 countries. The examination will illustrate Stearns’ statement that only through studying history can we grasp how and why things change. 3 The Bottling Plants During World War II, American businesses were forced to figure out how they could protect their long-­‐term marketing interests during a time of global conflict. The solution? Keep products in the public eye by associating them with the Allied cause.vi “As Richard Polenberg notes, with the availability of consumer goods limited by economic rationing, ‘businessmen were not primarily interested in motivating people to buy more, but by linking their product[s] with the war they hoped to keep alive brand name preferences, build up post-­‐war demand, and maintain good will.’”vii The war became an opportunity for product placement, public relations and public service, and The Coca-­‐Cola Company took advantage. In addition to traditional corporate wartime PR activities such as scrap metal drives, Coca-­‐Cola’s President Robert Woodruff did something rather unusual. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, “Coca-­‐Cola persuaded the U.S. War Department that Coke was crucial to the war effort. It was announced that ‘every man in uniform gets a bottle of Coca-­‐ Cola for five cents wherever he is and whatever it costs.’”viii Though it was a patriotic gesture, this will remain the starting point of one of the largest PR campaigns in history. “Woodruff’s gesture was undoubtedly a genuine act of patriotism, but his shrewd business sense and eye for publicity also prompted his magnanimity.”ix The effort to supply the armed forces with Coke was being launched when a telegram arrived from General Dwight Eisenhower's Allied Headquarters in North Africa on June 29, 1943, requesting shipment of materials and equipment for bottling plants and throwing the program into high gear.x “Within six months, a company engineer had flown to Algiers and opened the first plant, the forerunner of 64 bottling plants shipped abroad during World War II. The plants were set up as close as possible to 4 combat areas in Europe and the Pacific.”xi The War Department sponsored the Technical Observers (TO) program to deploy Coca-­‐Cola employees within traveling military units. “These ‘TOs’ traveled at the expense of the U.S. military and were aided in the creation of bottling operations in neutral and allied countries that did not already produce Coca-­‐Cola (or in some cases could not because of the disruptions of war).”xii Coke became a fixture at stage door canteens around the world and it inspired a new advertising campaign and slogan.xiii “The Global High Sign” By 1944, Coca-­‐Cola became known as “The Global High Sign.”xiv The slogan was adopted into a new advertising campaign that simultaneously boosted the morale of soldiers and laid the groundwork for becoming an international symbol of unity and refreshment. “Set in exotic locals such as Hawaii, Russia, Newfoundland and New Zealand, the ads portrayed grinning GI’s mixing it up and laughing over Cokes with British, Polish, Soviet and other Allies always with a caption along the lines of ‘Have a ‘Coke’ = a way of saying we’re with you.’”xv The use of the “=” symbol sends the message that the refreshing taste of Coca-­‐Cola is not private to Americans, but something that is understood across all cultures. “But it wasn’t just GI’s for whom Coke was a symbol of the American way. It was a symbol for the native population well. The presence of Coke did more than lift the morale of the troops. It gave the local people in the different countries their first taste of Coca-­‐Cola and paved the way for unprecedented worldwide growth after the war.”xvi One 1944 ad reads, “Kia Ora, says the New Zealander when he wants to give you his best wishes. It’s a down under way of telling you that you’re a pal and that your welfare is a matter 5 of mutual interest. The American soldier says it another way Have a Coke, says he, and in three words he has made a friend.”xvii A second 1944 ad reads, “There is an American way to make new friends in Newfoundland. It’s the cheery invitation Have a Coke an old US custom that is reaching ‘round the world. It says lets be friends reminds Yanks of home.” xviii Both advertisements are pictured below. As previously stated, the advertisements pictured above convey the message that the refreshing taste of Coca-­‐Cola is not private to Americans, but something that is understood across all cultures. Everyone understands the friendly gesture of a refreshing Coke – it is 6 synonymous with saying “Hello” or “Let’s be friends.” The U.S. bottling operations, accompanied by these advertisements, became a welcome sight across the globe. The Coca-­‐Cola Company continued its campaign efforts throughout the war with the addition of more tactics, including the hiring of over one hundred name bands to play concerts and drink Cokes at bases across the U.S.xix They also “sold thousands of copies of a ‘Know Your War Planes’ booklet – an ingenious appeal to war-­‐happy kids. The ‘Our America’ pamphlet series, designed for junior high students, told the story of the U.S. steel, lumber, coal, or agricultural industries with minimal advertising.”xx Again, though each of these gestures was done with patriotism, The Coca-­‐Cola Company saw a PR opportunity in the war and jumped on it. The Global Expansion When World War II began, “Coca-­‐Cola was bottled in 44 different countries, including those on both sides of the conflict.”xxi By the war’s end, five billion bottles of Coke were sold to G.I.s around the world and it was recognized as a brand favorite by American veterans.xxii But, G.I.s were not the only ones purchasing the beverages abroad. The Coca-­‐Cola Company’s efforts to get Coke to the American soldiers on the front lines had also introduced the beverage to citizens in other countries. For example, the drink was unknown in Iceland before the war, but it “achieved such popularity that the Prime Minister demanded that half of the sugar ration sweeten beverages for civilians, who agreed that Coke was ‘Heilnaemt og Hressandi’ (delicious and refreshing).”xxiii In addition, as the troops and TOs moved through different areas, contacts were made with various government officials. So, in the post-­‐war period of time, Coca-­‐Cola had 7 entre points that had not previously existed and discussions about more permanent bottling facilities started to take place. xxiv Coca-­‐Cola was poised for unprecedented worldwide growth. “From the mid-­‐1940s until 1960, the number of countries with bottling operations nearly doubled. As the world emerged from a time of conflict, Coca-­‐Cola emerged as a worldwide symbol of friendship and refreshment.”xxv As a postwar Coca-­‐Cola official acknowledged, World War II resulted “in the almost universal acceptance of the goodness of Coca-­‐Cola.”xxvi Conclusion To return to a previous quote, Stearns says, “Only through studying history can we grasp how things change; only through history can we begin to comprehend the factors that cause change; and only through history can we understand what elements of an institution or society persist despite change.”xxvii Stearns is correct in his statement. Through the study of history we are able to deduce how The Coca-­‐Cola Company changed from a mostly domestic brand to one recognized across the globe and the factors that caused the change -­‐ undoubtedly through the organization’s World War II PR campaign tactics. Coca-­‐Cola’s campaign involved smaller tactics including scrap metal drives, concerts on various U.S. military bases, and the production of books and pamphlets for war-­‐happy children. However, it’s the larger tactics of the “The Global High Sign” advertisements and pop-­‐up bottling systems that made the campaign successful and historically valuable, not only for the company but the PR industry as a whole. For The Coca-­‐ Cola Company, the campaign was a patriotic gesture, but one with the benefits of publicity and global growth. “As the Company’s unpublished history stated, the wartime program ‘made friends and customers for home consumption with 11,000,000 GIs [and] did [a] sampling and 8 expansion job abroad which would [otherwise] have taken 25 years and millions of dollars.’”xxviii Stearns also states that history teaches us by example.xxix Coca-­‐Cola’s campaign still benefits PR students today by providing an interesting case study and discussions on history, tactics and ethics. As evidenced through this paper, it is able to teach through example. With all of its benefits, it may be said that The Coca-­‐Cola Company’s World War II PR campaign won the war. i “Who We Are,” The Coca-­‐Cola Company, accessed January 26, 2014, http://www.coca-­‐ colacompany.com/careers/who-­‐we-­‐are-­‐infographic. ii “Highlights,” The Coca-­‐Cola Company, accessed January 26, 2014, http://www.coca-­‐ colacompany.com/annual-­‐review/2012/highlights.html iii “Who We Are.” iv Peter N. Stearns, “Why study history?,” American Historical Association, last modified July 11, 2008, http://reserves.library.kent.edu/eres/coursepage.aspx?cid=1541&page=docs. v Alan Pearcy, “Infographic: A history of PR campaigns,” Ragan’s PR Daily, September 22, 2011, accessed January 26, 2014, http://www.prdaily.com/Main/Articles/Infographic_A_history_of_PR_campaigns_9564.aspx#. vi Mark Weiner, “Consumer Culture and Participatory Democracy: The Story of Coca-­‐Cola During World War II,” Food and Foodways 6 (1996): 126. vii Weiner, “Consumer Culture and Participatory Democracy,” 126. viii Pearcy, “Infographic: A history of PR campaigns.” ix Mark Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-­‐Cola: The Definitive History of the Great American Soft Drink and the Company That Makes It (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 195. x “The Chronicle of Coca-­‐Cola: A Symbol of Friendship,” last modified January 1, 2012, http://www.coca-­‐colacompany.com/stories/the-­‐chronicle-­‐of-­‐coca-­‐cola-­‐a-­‐symbol-­‐of-­‐friendship. xi “The Chronicle of Coca-­‐Cola: A Symbol of Friendship.” Laura A. Hymson, “The Company that Taught the World to Sing: Coca-­‐Cola, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of Branding in the Twentieth Century,” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2011). xiii “The History of Coca-­‐Cola (6 of 10),” YouTube video, 10:57, posted by “frakdox,” January 16, 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lFfH1b-­‐tp-­‐0. xiv “Coca-­‐Cola Around the World, World War II,” Adbranch (blog), October 21, 2010, http://www.adbranch.com/coca-­‐cola-­‐around-­‐the-­‐world-­‐world-­‐war-­‐ii/. xv Sally Edelstein, “On the Front Lines with Coca Cola Pt II,” Envisioning the American Dream (blog), May 30, 2013, http://envisioningtheamericandream.com/2013/05/30/on-­‐the-­‐front-­‐ lines-­‐with-­‐coca-­‐cola-­‐pt-­‐ii/. xvi Sally Edelstein, “On the Front Lines with Coca Cola Pt II.” xvii Sally Edelstein, “On the Front Lines with Coca Cola Pt II.” xviii Sally Edelstein, “On the Front Lines with Coca Cola Pt II.” xii 9 xix Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-­‐Cola, 203. xx Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-­‐Cola, 203. xxi “The Chronicle of Coca-­‐Cola: A Symbol of Friendship.” xxii "The History of Coca-­‐Cola (6 of 10).” xxiii Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-­‐Cola, 198. xxiv “The History of Coca-­‐Cola (7 of 10),” YouTube video, 10:50, posted by “frakdox,” January 16, 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uOtPN7bD8I4. xxv “The Chronicle of Coca-­‐Cola: A Symbol of Friendship.” xxvi Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-­‐Cola, 212. xxvii Stearns, “Why study history?.” xxviii Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-­‐Cola, 212. xxix Stearns, “Why study history?.” 10 Bibliography “Coca-­‐Cola Around the World, World War II.” Adbranch (blog). October 21, 2010. http://www.adbranch.com/coca-­‐cola-­‐around-­‐the-­‐world-­‐world-­‐war-­‐ii/. The Coca-­‐Cola Company. “The Chronicle of Coca-­‐Cola: A Symbol of Friendship.” Last modified January 1, 2012. http://www.coca-­‐colacompany.com/stories/the-­‐chronicle-­‐of-­‐coca-­‐ cola-­‐a-­‐symbol-­‐of-­‐friendship. The Coca-­‐Cola Company. “Highlights.” Accessed January 26, 2014. http://www.coca-­‐ colacompany.com/annual-­‐review/2012/highlights.html. The Coca-­‐Cola Company. “Who We Are.” Accessed January 26, 2014. http://www.coca-­‐ colacompany.com/careers/who-­‐we-­‐are-­‐infographic. Edelstein, Sally. “On the Front Lines with Coca Cola Pt II.” Envisioning the American Dream (blog). May 30, 2013. http://envisioningtheamericandream.com/2013/05/30/on-­‐the-­‐ front-­‐lines-­‐with-­‐coca-­‐cola-­‐pt-­‐ii/. “The History of Coca-­‐Cola (6 of 10).” YouTube video, 10:57. Posted by “frakdox,” January 16, 2009. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lFfH1b-­‐tp-­‐0. “The History of Coca-­‐Cola (7 of 10).” YouTube video, 10:50. Posted by “frakdox,” January 16, 2009. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uOtPN7bD8I4. Hymson, Laura A. “The Company that Taught the World to Sing: Coca-­‐Cola, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of Branding in the Twentieth Century.” PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2011. Pearcy, Alan. “Infographic: A history of PR campaigns.” Ragan’s PR Daily. September 22, 2011. http://www.prdaily.com/Main/Articles/Infographic_A_history_of_PR_campaigns_9564. aspx#. Pendergrast, Mark. The Definitive History of the Great American Soft Drink and the Company That Makes It. New York: Basic Books, 2000. Stearns, Peter N. “Why Study History?.” American Historical Association. Last modified July 11, 2008. http://reserves.library.kent.edu/eres/coursepage.aspx?cid=1541&page=docs. Weiner, Mark. “Consumer Culture and Participatory Democracy: The Story of Coca-­‐Cola During World War II.” Food and Foodways 6 (1996): 126. 11