ALAN GILBERTONTHISPROGRAM

advertisement

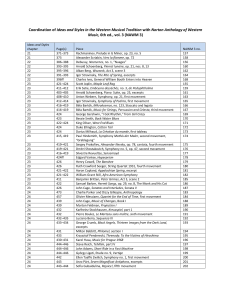

ALAN GILBERTONTHISPROGRAM Playing the last three symphonies of Mozart together in a program is a very intense but very powerful way of experiencing this music. They were composed within a very compressed period of time, but each is so distinct and so clearly defined, in terms of the worlds that Mozart creates in them, that there’s incredible variety and invention among these three iconic pieces. In the end, they still somehow intrinsically fit together. For any performer, approaching Mozart is uniquely challenging. The difficulty lies in how simple the music seems on the page: the notes in the score don’t appear ornate or complex in the way, say, they look in one by Strauss. Nevertheless, working with that relatively spare amount of information you have to develop a rich idea of what the music is about. The interpretation has to be stylish and shaped but, ultimately, human and natural. You have to tell the story that’s in the music: the story of Mozart is everybody’s story. NOVEMBER 2013 | 25 NOTESONTHEPROGRAM BY JAMES M. KELLER, PROGRAM ANNOTATOR The Leni and Peter May Chair Symphony No. 39 in E-flat major, K.543 Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K.550 Symphony No. 41 in C major, K.551, Jupiter Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart W olfgang Amadeus Mozart’s biography contains such an amazing procession of extraordinary experiences and achievements that it reads almost like an 18thcentury novel. One might think it was all made up; but then, of course, there’s the inescapable evidence that he did live and breathe — and write music unlike anything produced before, during, or after his lifetime. The story of his final three symphonies occupies a full chapter of this life-as-novel. More than two centuries after they were written, Mozart’s Symphonies No. 39 in E-flat major, No. 40 in G minor, and No. 41 in C major, Jupiter, stand at the summit of the symphonic repertoire, where they keep company with a small and supremely select group of masterpieces by A-list composers. Mozart, however, seems to have scarcely broken a sweat in writing them. Incredibly, all three of these symphonies were produced in the space of about nine weeks in the summer of 1788. He began writing Symphony No. 39 around the beginning of June, not quite a month after Don Giovanni received a lukewarm reception at its Vienna premiere. He finished the E-flat-major Symphony on June 26, and went on to complete the succeeding symphonies on July 25 and August 10. Each is a full-scale, four-movement work in the late Classical style, unlike the threemovement Symphony No. 38, Prague, which 26 | NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC IN SHORT Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg, Austria Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna Works composed and premiered: composed in the summer of 1788 — Symphony No. 39 in June (completed June 26), Symphony No. 40 from then through July 25, Symphony No. 41 from July 25 through August 10. A recently uncovered document reveals that Symphony No. 40 was played in a concert organized by Baron Gottfried van Swieten, although no date is given. Antonio Salieri conducted the Symphony No. 40 at the Burgtheater in Vienna on April 16-17, 1791, with instrumentation slightly revised from the original version. Premieres of Symphonies Nos. 39 and 41 are unknown. New York Philharmonic premieres and most recent performances: Symphony No. 39, premiered January 9, 1847, Henry C. Timm, conductor; most recently played June 9, 2012, Pinchas Zukerman, conductor. Symphony No. 40, premiered April 25, 1846, Henry C. Timm, conductor; most recently performed October 7, 2006, at Baker Hall in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Lorin Maazel, conductor. Symphony No. 41, premiered January 13, 1844, Denis G. Etienne, conductor; most recently performed March 3, 2010, Alan Gilbert, conductor Estimated durations: Symphony No. 39, ca. 28 minutes; Symphony No. 40, ca. 24 minutes; Symphony No. 41, ca. 30 minutes Mozart had written two years earlier. Twelve movements in nine weeks would mean that, on the average, Mozart expended five days and a few hours on the composition of each movement. That doesn’t figure in the fact that he was writing other pieces at the same time, or that he was also giving piano lessons, tending a sick wife, enduring the death of a six-month-old daughter, entertaining friends, moving to a new apartment, and begging his fellow freemason Michael Puchberg for assistance that might see him and his family through what was turning into an extended financial crisis. In one of his beseeching letters to Puchberg, Mozart mentioned that he had hopes for some income from two concerts that were to take place in the Vienna Casino the following week. But none of the city’s newspapers made mention of the concerts, and it seems probable that they were cancelled due to lack of audience interest. If they did take place, Mozart was apparently not encouraged by them, for it appears that he never performed in public thereafter, except to conduct opera. A 2011 article by the musicologist Milada Jonášová introduced a newly discovered document revealing that the G-minor Symphony was played in a concert under the patronage of Mozart’s friend, Baron Gottfried van Swieten. Although the document does not say when the concert took place, the piece may have been written for this event rather than for the Casino concerts. The Mozart scholar Christoph Wolff states in his new book, Mozart at the Gateway to His Fortune, that “it makes sense to assume that all three symphonies were intended for presentation in the concert series organized by van Swieten.” Mozart’s triptych represents his last word in the medium of the symphony, which itself was among the supreme musical advances of the 18th century. He undoubtedly had every A Memorable Minuet-and-Trio The third movement Menuetto of Mozart’s Symphony No. 39 is unusually boisterous — a sort of peasant’s minuet — and the contrasting Trio contains one of the composer’s most endearing dance tunes, a lilting melody from the first clarinet with delightful echo effects from the flute, all above a murmuring accompaniment from the second clarinet. Mozart scholar Neal Zaslaw, currently supervising an overhaul and updating of the Köchel catalogue, which is the definitive guide to all matters Mozartean, says that this Trio is not merely in the style of a Ländler (an Alpine folk dance which is the forerunner of the waltz) … but is actually based on a real one, given out by a pair of clarinets, which were favorite Alpine village instruments. expectation of living well into the 19th century; and although that is not what happened, at least he had another three and a half years in which he might well have written further symphonies. But since he didn’t, these works stand as the apex of his achievement in symphonic music, and in their strikingly different characters they not only draw together developments that had enriched his orchestral music to that point but also offer hints of what the future might have held. These three symphonies have been minutely analyzed over the years — especially Nos. 40 and 41 — and they have proved so rich in their structural details that the analytical conversation continues at full force to this day. One can dissect their harmonic structures, their deployment of themes, their contrapuntal subtlety, and the mastery of their instrumentation and yet fail to convey the exceptionally well-wrought personalities that each makes evident even at first hearing. Each is sublimely beautiful, but elicits a very different response. NOVEMBER 2013 | 27 Like the Prague Symphony, Symphony No. 39 opens grandly, with a slow, darkly dramatic introduction in which the orchestral texture and the harmonic dissonance increase to near the breaking point. (The composer is very much in Don Giovanni territory here.) This gives way to a lyrical Allegro in which buoyancy rubs shoulders with measured grace. The movement’s two main themes are set apart by both their contrasting melodic character and their instrumentation; the first is conceived for the strings, while the second employs the rich texture of Mozart’s beloved clarinets — two of them, playing in thirds. The dotted rhythms of the introduction appear again in the slow movement, a subtle Andante con moto. Mozart employed a modest instrumentation for this symphony, but the second movement grows still more economical by foreswearing the trumpets and timpani. The resultant intimacy suggests chamber music, especially in light of the delicate writing for one-on-a-part winds. Often the third movement is the least memorable in a Classical symphony, perhaps with a throwaway minuet that serves only to cleanse the palate between the more imposing courses of the slow movement and the finale. But in Mozart’s Symphony No. 39, the third movement may be the most memorable, thanks especially to its irresistible Trio section. Still, it steals none of the finale’s thunder. In this final movement, a single theme undergoes all manner of rhythmic and contrapuntal exploration, very much à la Haydn, without ever coming off as recherché. The Salieri Connection Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 figured on a program of April 16-17, 1791, in Vienna, conducted by the distinguished Antonio Salieri, who had been named Kapellmeister of the Vienna Court in 1788, the same year Mozart composed his last three symphonies. To many music lovers the mention of Salieri inevitably brings to mind the stories that make him complicit in Mozart’s death, myths that proved potent to Romantic imaginations of the 19th century and that fueled Peter Shaffer’s marvelous play Amadeus (which, from the moment it was premiered in 1979, people have had trouble remembering that it is a work of fiction). It would be hard to find a reputable historian today who finds the legend that Salieri committed murder anything less than preposterous, although Mozart could be suspicious of Salieri, and several of his letters underscore that he felt the composer sometimes tried to undermine his endeavors. Whether or not his suspicions were well founded, things had gotten onto a more The rival? F. Murray Abraham as Antonio Salieri in the 1984 film Amadeus collegial track by 1791. Six months after Salieri conducted the G-minor Symphony, he accompanied Mozart to a performance of the latter’s newly unveiled opera The Magic Flute, to which he reacted with demonstrative enthusiasm. Following Mozart’s tragically early death, almost certainly the result of rheumatic inflammatory fever (or “military fever,” as it was known at the time), the composer’s widow sent their elder son, Franz Xaver, to take music lessons from Salieri. 28 | NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC Symphony No. 40 is a work of Sturm und Drang, one that seems almost to depict inner demons as it ranges from the quirky and the unsettling to the downright terrifying. Mozart had traced a suggestion of this territory 15 years earlier in his Symphony No. 25 (K.183/173dB), also in G minor. That work was a fine achievement, arguably the earliest of his symphonies that modern music lovers would be very dejected about doing without. Mozart was right to esteem it. In 1783 he wrote from Vienna asking his father back home in Salzburg to send the music for that “Little” G-minor Symphony, and it is not difficult to imagine him revisiting the work when he came to write the No. 40. These would be the only two symphonies he composed in minor keys (an early D-minor one, not included among his canonical symphonies, was just the overture extracted from his oratorio La Betulia liberata), and in the earlier of the two he had already worked out essential harmonic and structural implications gained by composing a symphony in the minor mode. The Symphony No. 40 marks an immense advance in the richness and generosity of themes, the intense effect of chromaticism, and the overall expressivity born of masterly symphonic orchestration. It links the sentiments of the 18th century to those of the 19th, and as such it was one of the rather few large-scale works by Mozart to remain steadfastly in the repertoire through the Romantic era. In Symphony No. 41, which later picked up the nickname Jupiter, Mozart seems intent on showing off his sheer brilliance as a composer. Its emotional range is wide indeed, prefiguring the sort of vast, expressive canvas that would emerge in the symphonies of Beethoven. In this work’s finale Mozart renders the listener slack-jawed through a breathtaking display of quintuple counterpoint, and that in itself may be viewed as looking both backward — to the sort of contrapuntal virtuosity associated with Bach and Handel — and forward, to the dramatic power of fugue that is demonstrated in many of Beethoven’s greatest compositions. What’s in a Name? As with so many musical nicknames, the one for Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 did not originate with the composer. Vincent Novello, the English composer and publisher, visited Mozart’s widow and their son Franz Xaver in 1829. Novello recounted: “Mozart’s son said he considered the finale to his father’s Sinfonia in C — which Salomon christened the Jupiter — to be the highest triumph of Instrumental Composition, and I agree with him.” Novello would have been referring here to the German violinist Johann Peter Salomon, who established himself as an impresario in London and who arranged Joseph Haydn’s two residencies in Great Britain in the 1790s. This origin of the “Jupiter” nickname rings true, as the earliest concert programs to use the word were Scottish and English, and the first printed edition to put it on the title page was a piano transcription of the symphony published in London in 1823. A drawing of Mozart, 1789 NOVEMBER 2013 | 29 The Jupiter Symphony quickly earned a reputation as a work of exceptional qualities. In 1798, a reviewer for Leipzig’s Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung referred to Mozart’s “formidable Symphony in C major, in which, as is well known, he came on a little too strong.” But soon commentators adopted tones of almost universal adulation. By the time Georg Nikolaus von Nissen published his groundbreaking Mozart biography, in 1828, the tenor was firmly set: “His great Symphony in C with the closing fugue is truly the first of all symphonies,” declared Von Nissen. “In no work of this kind does the divine spark of genius shine more brightly and beautifully.” Instrumentation: Symphony No. 39 calls for flute, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. Symphony No. 40 employs flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, and strings. Symphony No. 41 requires flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. At the Time In 1788, when Mozart was writing his Symphony Nos. 39, 40, and 41, the following events were taking place: In the United States, over the course of the year more than eight states ratify the Constitution (left) and enter the Union; New York City is designated as the country’s first federal capital; in New Orleans, a fire destroys much of the city and kills 25 percent of its population. In England, King George III demonstrates his first extended episode of mental instability, which causes a crisis in Parliament; in London, the newspaper The Daily Universal Register changes its name to The Times,. In France, the Day of Tiles revolt takes place in Grenoble, an event that is seen as one of the first that would lead to the French Revolution; Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun paints Marie Antoinette (far left); and Antoine-François Callet paints Portrait of Louis XVI (left). — The Editors 30 | NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC