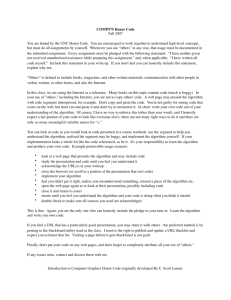

Culture and getting to yes : The linguistic

advertisement