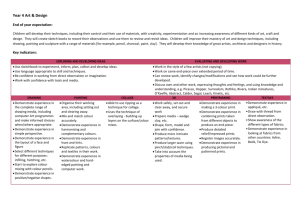

Women and children in prints after Chardin

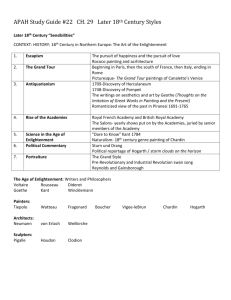

advertisement