Untitled - Our Lady of the Black Hills Catholic Church

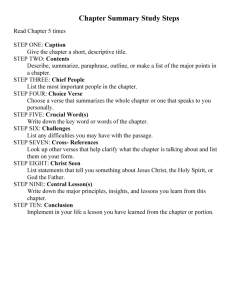

1

2

3

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

The well-proportioned and simple interior has three naves divided by 12 columns on each side (standing for the 12 apostles?), made of Greek marble with Corinthian capitals and dosserettes with crosses.

In 1514 - 1520 the floor was raised above the original level and the columns lifted up above the new floor, spoiling to a certain extent, the beauty of the arches. In the spandrels of the arches there are simple faded Renaissance freschi of saints’ figures.

When Justinian entrusted the basilica to Agnellus he gave him unlimited powers of renovation, ordering him only to remove all the images that contrasted with the official religion of the Empire. We will see that

Agnellus removed most traces of the Arian Theodoric and his court, but the apse-mosaic ordered by

The extremely simple apse was rebuilt in 1950 after the damage wrought in WWII. The four porphyry columns are marvelous: the two in front have Byzantine capitals in the shape of a basket and the two behind have and Egyptian-Alexandrian style that was part of the ancient ciborium. The Roman altar-table dates from the 6C. A 6C “pluteus” on the extreme left of the altar rail shows a decoration with peacocks and a rich vine decorated in leaves coming out of the cantarus on the back of the prophet Daniel in a loincloth, above a vigorous acanthus plant flanking 2 recumbent lions, all referring to the eucharist.

The three transennas (windows) of the 6C and 7C are finely fretworked in Eastern style.

4

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

North Wall of Nave, Lowest Zone: Male Procession Detail, Joachim and Sabinus

All the faces and garments of the martyrs are depicted by the same weak contrasts in color, the robes all fall in identical folds. Perhaps the idea of presenting this long procession derives from the figures of the apostles on the domes of the Baptistery of the Orthodox and the Baptistery of the

Arians. Yet the spirit and meaning are different here. The train of the Blessed is moving so slowly as to give the impressed that the single saints have even stopped, not to be admired by the faithful going around the nave in wonder, but rather inviting them to move at a processional pace all

The whole of the procession cannot be embraced at a glance, so long it is. The artist had no fear of repeating the same vertical rhythms; indeed he takes pleasure in this motif and repeats it ad infinitum, treating the composition as if it were a murmured litany flowing from a single chord, this last effect achieved by robing all the saints in identical garments, dead white save for a few ornamental letters on the pallia and the dark clavi ornamenting the mantles.

Although the elements of this composition are constantly repeated, they are never monotonous.

The martyrs have different gestures, poses, draperies, and faces. There are marked differences in the way they carry their crowns, the way their feet are posed slightly apart on the grassy meadow, their heads, each singularly individual, their robes, the draperies flowing in vertical, oblique, curved or broken lines, with soft or hard, schematic or fluent outlines. There are both harmony and contrast. So each figure stands out, always different from the one nearest it.

5

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

North Wall of Nave, Lowest Zone: Male Procession Detail, Martin + Saint

The only martyrs’ figures to break with this pattern are St. Lawrence (robed in a golden tunic) and St. Martin at the head of the procession. He alone is dressed in an amethyst robe and stands as though presenting all the rest to the court of the King of heaven.

6

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

North Wall of Nave, Lowest Zone: Male Procession Detail, Christ Enthroned

The group representing Jesus enthroned among angels -- partly restored -- show a tendency to greater symmetry. The Redeemer and the angels which stand guard are all perfectly still figures, all placed on the same plane, all in the same frontal position.

Impassive, rigid, they seem to gaze fixedly toward some distant ideal point. Lower down, on the emerald green meadow, the flowers of heaven grow, with white and crimson petals.

the congiarium as depicted on the Arch of Constantine. There the emperor is show seated on a throne in the center, while on either side senators stand ready to receive his bounty in the folds of their togas.

As we will come to expect in our consideration of Byzantine icons, this is a representation of Christ Pantocrator, seated on a throne, blessing with his right hand, and holding in his left a scroll or a book. His bearded face is surrounded by a nimbus

(halo) marked by a cross. The throne on which he is seated would recall both the

Byzantine imperial throne as well as the throne for the cross in the dome of the

Baptistery of the Arians.

7

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall of Nave, Procession of Female Martyr-Virgins

22 virgin-martyrs tread softly, as if weightless, on a meadow strewn with roses and lilies, carrying the symbolic crowns of martyrdom in their hands. Inscriptions above the figures identify them as Eugenia, Sabina, Cristine, Anatolia, Victoria, Pauline, Emerenzia,

Daria, Anastasia, Justine, Felicity, Perpetua, Vincenza, Valerie, Crispine, Lucy, Cecilia,

Eulalia, Agnes, Agatha, Peladia and Euphemia.

8

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall of Nave, Procession of Female Martyr-Virgins: Detail of the Harbor of Classe

Like the procession of male martyrs moving from Theodoric’s palace in Ravenna, the procession of virgin martyrs processes from the harbor and town of Classe. Two towers mark the entrance to the port where three large ships are visible; one of these has its sails unfurled.

9

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall of Nave, Procession of Female Martyr-Virgins: City Walls of Classe

But just as certain characters in the mosaic of Theodoric’s palace were effaced when this building was refitted for Catholic worship, so some characters originally depicted on the city walls of Classe have likewise been effaced. The original contours of these figures may still be discerned owing to the different material employed which had to be similar to the stone top of the walls.

10

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall of Nave, Procession of Female Martyr-Virgins

Like the male martyrs, the female virgin-martyrs are all in the same three-quarters frontal attitudes.

Their robes are extremely ornamented, quite differently from those of the male martyrs. From the virgin-martyrs’ high-swept hair, long white veils fringed with blue fall over lovely robes made of cloth-of-gold, on which stars, circles, and segments in red, green, yellow and brown are designed. On these splendid garments many pearls and virgin-martyrs. Their oval faces enhance their big, dreamy eyes, their thin lips are smiling slightly.

Between one figure and the next is a palm, its branches thin and few; this way the golden background throws its iridescent light on the figures, enveloping them in a caress. In this stupendous procession, everything is expressed in terms of light, rhythm, and color.

There are 22 virgin-martyrs, yet they create the impression of being an interminable train. Conceived as a figured litany, each bears her name over her head.

11

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall of Nave, Procession of Female Martyr-Virgins: Detail, Agnes and

Agatha

All the virgin-martyrs are posed in a similar manner, yet in the details marvelous and surprising differences may be seen: the faces are less or more rounded; the lips are smiling sweetly or more tightly closed; the eyes gaze now fixedly, now seeming to wonder at some far-off melody; the hair is brown, black, or fairer than gold.

designs enriching the lovely golden robes. Pearls, amethysts, emeralds and rubies are lavished everywhere.

The white of the fabrics is achieved in various tones: the long robes ornamented with the clavi are depicted by employing enamel tesserae, gleaming with reflected light, suggesting they are silk or damask; the veils over the heads, instead, are made with tesserae of rough marble, so they tend to absorb, not to reflect light, suggesting they are wool or linen.

Nevertheless, the rhythm is always even and the few colors used in contrast, such as in the sandals and in the gem-studded crowns, alternately green and red, never spoil the harmony.

12

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall of Nave, Procession of Female Martyr-Virgins: Detail 3 Magi

Corresponding to the figure of St. Martin at the head of the procession of the male martyrs are the figures of the 3 magi bearing gifts at the head of the procession of the virgin-martyrs.

Although the magi are completely restored in the upper part of the body, the variety of colors they must have shown in their sparkling Eastern clothes can still be imagined.

It is also interesting to compare this representation of the magi with that on the bottom

Following the typical layout of this scene, the magi are presented in motion. Thus they make a contrast with the procession of the virgin-martyrs who solemnly advance with heads reverently bowed.

13

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall of Nave, Procession of Female Martyr-Virgins: Detail 3 Magi Close-Up

Following patristic interpretation of the gifts borne by the magi, the artist makes a theological point: the gold offered by the first of them (in a gesture reminiscent of foreign potentates offering their crowns to the emperor) is an act of homage to Christ’s kingship; the frankincense offered by the second is an allusion to his divinity; and the myrrh offered by the third is a prophetic symbol of Christ’s passion. Like the virginmartyrs and the male martyrs each of the magi is identified by name in a written

14

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall of Nave, Procession of Female Martyr-Virgins: Detail Gaspar

.

.

When the upper part of this mosaic was restored by Kibel in the 19C, he eliminated the crowns on their heads, replacing them with the present Phrygian caps. The caps were modeled on the images sculpted on the front of the 5C sarcophagus of Bishop Isaac at the entrance of the Basilica of S. Vitale and on the pyx of S. Quiricus and Juditha in the

Archepiscopal Museum.

15

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall of Nave, Procession of Female Martyr-Virgins: Detail Virgin Enthroned

Paralleling the panel of Christ enthroned among four angels in the procession of the male martyrs, the BVM holding the Christ-Child is enthroned among four angels. The throne on which the BVM is seated is not quite as sumptuous as that for the

Pantocrator, but it is clearly imperial. Mary is draped from the shoulders in a royal purple planeta; her right hand is raised in blessing, while her left both encircles and points to the child on her lap. Christ’s right hand echoes his mother’s gesture, but effect a medallion about their heads. The child’s left hand is hidden in the folds of his toga, bright white with gold-brown clavi. The cruciform nimbus encircles the child’s head. Note that both figures are presented completely frontally, directly confronting with viewer.

16

Ravenna, S. Apollinare Nuovo, constructed c. 500 - 525; consecrated 561

South Wall, Top Zone, Panel 1: The Last Supper

17

18

Stavelot, Portable Altar, c. 1140-1160

19

The complex image before us is the top-view with a depth of 6 ¾ in (17 cm) of the Stavelot Portable Altar, fabricated c. 1160 of champleve enamel and gilt copper. By this stage Western Europe has become “Christendom”, a particular fusion of a Christian religious worldview and a medieval political and cultural system. The most precious materials and careful craftsmanship in Christendom were devoted to religious objects, those touching the consecrated eucharistic elements demanding the highest standards. The central rectangle of this object consists of a large rock crystal containing martyrs’ relics wrapped in a band marked “Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus”; the paten and chalice would be placed directly over this crystal. Surrounding this ritual focal point are scenes explore the three panels of the lower zone, then the three of the upper zone, and conclude by examining the eight scenes in the middle zone.

20

The three panels of the lower zone begin the memorializing of Christ’s paschal mystery. On the left (from our perspective) Christ offers the chalice and host to the disciples gathered at table with him. Notice how differently this Western artist depicts the communion of the apostles: a single Christ figure offers a chalice to some disciples and a host to others; either species is sufficient for holy communion. Crowned with a cruciform nimbus and clothed in tunic and overgarment, Christ stands at the table with feet firmly planted on the ground, attributes that will be echoed in the upper zone’s depiction of him accepting the cross and being crucified. By this means the artist thus subtly presents the Last

Supper as the anticipatory embodiment of Jesus’ self-sacrifice. By this means the artist profoundly theologizes that the consecrated elements centered in

The central panel illustrates a crowd of Jewish leaders before Pilate, robed and enthroned as a contemporary northern European ruler. The banners spell out their respective stances toward Jesus, Pilate’s declaring “I am innocent of this blood” while the Jewish leaders’ banner proclaims “His blood be upon us and our children”.

The right hand panel (from our perspective) depicts Jesus, stripped and bound to a pillar, being scourged by two male figures dressed in the clothing of medieval law officers. There may be a subtle message in the fact that all three of the figures’ feet escape the framework of the panel (in contrast to every other figure except the Jewish leader in the other panels).

The theological message is inescapable: these panels are to be read horizontally, not only as a chronological unfolding of the events of the Passion, but as a meditation on the power of Christ’s blood: redeeming for believers and condemning for those who accuse, judge, and torture him.

21

The panels of the upper zone continue the meditation on the paschal mystery of

Christ begun in the lower zone. To the left (from our perspective) is a panel showing Christ as the Man of Sorrows accepting his cross. He is crowned with thorns within his cruciform nimbus and clothed with the brightly colored cloak by which the soldiers who tortured him mocked what they thought were his political ambitions.

In the center panel Mary and the Beloved Disciple flank the Crucified

Jesus, lifting their hands to their cheeks in a stylized expression of grief. Above them the sun and moon observe the scene, indicating that the death of God is a cosmic event, not just the unfortunate conclusion to a religious reformer’s life.

Notice how this panel depicts the theology of the Gospel of John: Christ “reigns fulfillment, his feet not so much nailed to the cross as standing as the Just One on the redeemed earth, his hands not so much nailed in torment as uplifted in offering.

On the right (from our perspective) an angel announces to the women who have come to anoint Christ’s body that he has risen from the dead. The cover has been removed from the empty tomb and the women discover that their anointing spices are not needed since Christ’s body is no longer bound to the sad entropy of a death-haunted world.

From a theological point of view the panels of the upper zone, like those of the lower, are not only to be read chronologically as the continuation of the

Passion-Resurrection narrative, but as a meditation on Christ’s body: the body treading the final journey every human must make, the body torn and transfigured in self-offering, the body no longer constrained by the limits of this world. Thus lower and upper zone together theologize the meaning of the consecrated elements placed between them.

22

The central zone of the Stavelot Portable altar initiates another theological program, this time centered on sacrifice. In the four corner scenes we see (beginning with the lower right, from our perspective) Abel offering the animal sacrifice that God accepted in contrast to the grain offering of his brother Cain; the bread and wine offered in sacrifice to God by the mysterious figure of the priest-king Melchizedek (whose name in Hebrew means “righteous king”); the divinely interrupted sacrifice of Isaac by his father Abraham; and Moses lifting up a bronze serpent as a curative device for those

Israelites bitten by seraph serpents in their desert wandering. Each scene is labeled with sacrificial terminology bearing deep theological resonances for Christians: “hostia Abel” (the offering of Abel), “sacrificium Melchisedec” (the sacrifice of Melchizedek), “immolatio Isaac” (the immolation of Isaac), “exultatio serpentis” (the lifting up of the serpent). Not only are the first three scenes explicitly mentioned in the Roman Canon, the consecratory prayer that would be prayed at this altar, but all four of the scenes function as types of Christ: like Abel, Christ offers himself as an innocent Lamb; like

Melchizedek, Christ is sacrificed to the Father under the appearances of bread and wine; like Isaac,Christ is obedient to his Father even unto death; and like the serpent, Christ is lifted up to heal those who gaze upon him in the consecrated elements that are lifted up in the liturgy. Not only are these four images related to each other as types of Christ, they also relate on a vertical axis to the panels beneath and above them. Thus the spilling of the lamb’s blood in Abel’s sacrifice resonates with Christ’s scourging at the pillar immediately below it and Melchizedek’s offering of bread and wine echoes the Last Supper panel below it; the wood bound on Isaac’s shoulders finds a mirror in the cross placed on

Christ’s shoulders and the exultation of the serpent by which a demonic symbol becomes an instrument of healing parallels the exultation of Christ by whose assumption of sin-ridden human nature, that nature is divinized.

The center quatrefoil continues with two further scriptural types, and concludes with a contrast between the the doors of the city gates of Gaza on his shoulders, an exploit recounted in Judges 16:1-3. On the right, Jonah is vomited forth alive from the belly of the sea creature that had swallowed him. Both the judge and the prophet were interpreted as types of Christ: like Samson, Christ shattered the gates of hell and broke down the locked portals of heaven; like

Jonah, Christ came forth after three days from the belly of death.

The final two images may cause us some difficulty. At the top, the crowned female figure dressed in multicolored royal robes and carrying a cross as a victory banner and a chalice represents the victorious Christian Church; in contrast at the bottom, the blindfolded female figure dressed in commoners’ clothing and carrying three instruments of

Christ’s Passion (the sponge soaked in sour wine, the spear that pierced his side, and the crown of thorns) represents a

Judaism willfully blind to God’s actions in Christ. Notice that the vertical axis relates the Church to Mary and the Beloved

Disciple standing at the foot of the cross, while the Synagogue relates to the Jewish leaders before Pilate declaring that

Christ’s blood would be upon them and their children. Although most of the theological program enshrined in the

Stavelot Portable Altar is of admirable sophistication and insight, its anti-Semitism would be problematic for contemporary Catholics.

The major implication I would suggest for contemporary piety and practice generated by contemplating the

Stavelot Portable Altar is the deeply scriptural foundations of our eucharistic worship. As St. Jerome said so long ago:

“Ignorance of the scriptures is ignorance of Christ”. The fact that Jesus’ spirituality was deeply grounded in the Law, the

Prophets, and the Writings, should make us yearn to be formed by the same living and revelatory Word of God. Frankly, unless we have some understanding of the old covenants with Noah, Abraham, Moses, and David, we will have little understanding of the new covenant prophesied by Jeremiah, heralded by John the Baptizer, and inaugurated and fulfilled by Jesus. Unless we understand the covenant signs and stipulations – the rainbow, circumcision, Torah, and the

Messiah – we will have little appreciation for the covenant signs and stipulations of the holy eucharist and the Sermon on the Mount. How much richer would our Masses be if we were to study the scriptures before coming to the Liturgy of the Word and if we were to take the texts of the Psalms as the songs on our lips and prayers of our hearts!

23

The complex image before us is the top-view with a depth of 6 ¾ in (17 cm) of the Stavelot Portable Altar, fabricated c. 1160 of champleve enamel and gilt copper. By this stage Western Europe has become “Christendom”, a particular fusion of a Christian religious worldview and a medieval political and cultural system. The most precious materials and careful craftsmanship in Christendom were devoted to religious objects, those touching the consecrated eucharistic elements demanding the highest standards. The central rectangle of this object consists of a large rock crystal containing martyrs’ relics wrapped in a band marked “Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus”; the paten and chalice would be placed directly over this crystal. Surrounding this ritual focal point are scenes explore the three panels of the lower zone, then the three of the upper zone, and conclude by examining the eight scenes in the middle zone.

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

We turn at last to artworks of the century to which we have just bid farewell. Emil Nolde was one of the leading figures in German Expressionism in the early 20 th C. One of his earliest religious works was this oil painting of 1909 entitled “The Last Supper”. Note the mask-like faces of the disciples, not caricatures so much as intense, individualized personalities. The figures are forced into a small space, in the first of the picture, which increased the intensity of the mood of tragedy, and the yellow-green of their faces and the red on their robes make them resemble so many flares in the surrounding darkness and add to the excitement of the scene. Christ’s position is central: he is shown with a longer and larger face than the rest; he wears a white under-garment, and his hands are quietly clasped around the central chalice, with its slight tinge of blue. Judas in the upper left-hand corner has turned his face away for the other disciples, and they close their ranks as a circle of loyalty around their Master.

What message does this intense picture have for us? First, note the combination of well the expressively distorted hands. Here we get some apprehension of the cost of Jesus’ selfsacrifice, a realization that may awaken in us a deeper appreciation for his actions.

Second, the disciples around the table are anything but plaster saints. Their faces betray the same greed, haughtiness, gluttony, and lassitude that may be glimpsed on the face of

Judas. They are sinners like the rest of humanity. But what distinguishes them from Judas is their willingness to stay focused on Christ. It is not their unaided self-improvement that will make them worthy of their Lord; they will stumble and fall, even at times of deepest religious significance. But recognizing that they are sinners, they are willing to keep their eyes fixed on the Christ who accepts them as they are and forgives their sins.

Third, although one might interpret the extended hands of the disciples as a closing of the ranks against Judas, I think it is more likely a statement of the character of authentic

Christian community: not a static collection of finished products but rough projects supporting each other on the way.

35

![WALKER APAH Work 1: [left] Christ as the Good Shepherd, mosaic](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008199063_1-917d961612a5fa9b320b28077d9ae06b-300x300.png)