WORKING PAPER NO: 438 Market Segmentation of Facebook Users

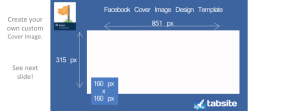

advertisement