article 8 - TowsonPDClass

advertisement

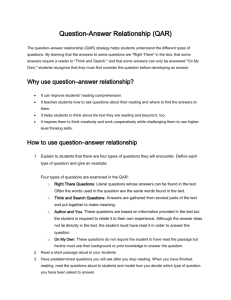

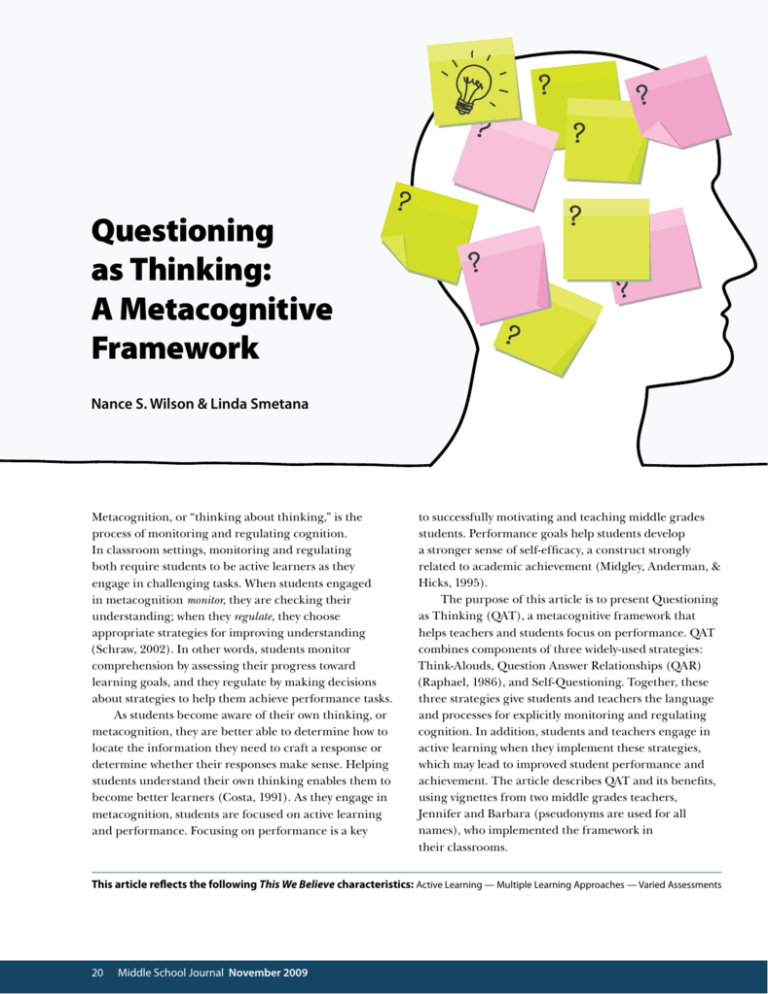

Questioning as Thinking: A Metacognitive Framework Nance S. Wilson & Linda Smetana Metacognition, or “thinking about thinking,” is the process of monitoring and regulating cognition. In classroom settings, monitoring and regulating both require students to be active learners as they engage in challenging tasks. When students engaged in metacognition monitor, they are checking their understanding; when they regulate, they choose appropriate strategies for improving understanding (Schraw, 2002). In other words, students monitor comprehension by assessing their progress toward learning goals, and they regulate by making decisions about strategies to help them achieve performance tasks. As students become aware of their own thinking, or metacognition, they are better able to determine how to locate the information they need to craft a response or determine whether their responses make sense. Helping students understand their own thinking enables them to become better learners (Costa, 1991). As they engage in metacognition, students are focused on active learning and performance. Focusing on performance is a key to successfully motivating and teaching middle grades students. Performance goals help students develop a stronger sense of self-efficacy, a construct strongly related to academic achievement (Midgley, Anderman, & Hicks, 1995). The purpose of this article is to present Questioning as Thinking (QAT), a metacognitive framework that helps teachers and students focus on performance. QAT combines components of three widely-used strategies: Think-Alouds, Question Answer Relationships (QAR) (Raphael, 1986), and Self-Questioning. Together, these three strategies give students and teachers the language and processes for explicitly monitoring and regulating cognition. In addition, students and teachers engage in active learning when they implement these strategies, which may lead to improved student performance and achievement. The article describes QAT and its benefits, using vignettes from two middle grades teachers, Jennifer and Barbara (pseudonyms are used for all names), who implemented the framework in their classrooms. This article reflects the following This We Believe characteristics: Active Learning — Multiple Learning Approaches — Varied Assessments 20 Middle School Journal November 2009 Introducing Questioning as Thinking (QAT) Barbara, a seventh and eighth grade science teacher, and Jennifer, a seventh and eighth grade language arts teacher, team-teach in a rural Midwestern middle school. They are also members of the school leadership team and have worked together to improve literacy across the content areas at their school. Barbara and Jennifer see learning as something that requires reasoning, flexible thinking, problem solving, and reflection (Rice & Dolgin, 2005), and they understand that early adolescence is a time of great intellectual growth during which students benefit from active learning experiences (Kellough & Kellough, 2008). Barbara and Jennifer had wanted to find a metacognitive framework that would guide their students in becoming active learners who think about text, and they found Questioning as Thinking (QAT). QAT is a metacognitive framework that allows teachers and students to actively incorporate strategies for asking and answering questions. In the first vignette, Jennifer is modeling active reading for her students using QAT (Figure 1). She has created a learning environment in which students are encouraged to take on challenging tasks, process deeply, and focus on performance so that they can feel good about themselves as students as they become independent thinkers and learners; her students are engaging in metacognition (Midgley, Anderman & Hicks, 1995). Notice how Jennifer shares her thinking about the text with students as she asks questions that monitor and regulate her thinking. Questioning is an effective place to begin metacognition instruction because it is a daily part of the school experience (Neufeld, 2005). Teachers ask students questions to assess comprehension of text, lecture, and hands-on experience. The application of different types of questions leads to the implementation of different metacognitive strategies. For instance, a science teacher may ask, “What is a homogeneous mixture?” A student may respond by scanning a written text for the answer; he may refer to an experiment, a kind of visual text, in which the class worked with different mixtures; or, he may use his prior knowledge of the word mixture to connect with his understanding of matter as gathered from within the written or visual text. In each case, the student is engaging in metacognition; he is using a strategy to respond to the question and then monitoring the application of this strategy to determine Figure 1 Jennifer models metacognition before reading a memoir to her seventh grade students. As we begin reading the first memoir, “My Mother’s Blue Bowl,” I want to first look at the title. This title is interesting. As I read it, I ask myself an On My Own question. What do I already know that I can connect to the text? This is important because it is using the pre-reading strategy of thinking about things I already know that can connect me to the text. I immediately think of two blue crystal bowls my own mom has in her china cabinet—one was a gift from my father, and we only use it on special occasions like holidays, and the other is a Swedish crystal bowl that my sister and I bought for her so that, eventually, we would both have a blue bowl. I wonder if the blue bowl that the author is talking about has the same importance in her family as the blue bowls have in my family? I am also going to use what I know about memoirs to get me ready to read the text. From our previous discussions, I know that a memoir is about a specific moment in time that is important in shaping who the author is. I’m expecting this to revolve in some way around this bowl and for the essay to tell me the importance of it. This is my purpose in reading this, and I need to keep this in mind as I read the memoir. Questioning as Thinking provides opportunities for teachers to demonstrate thinking processes. www.nmsa.org 21 QAT is a metacognitive framework that allows teachers and students to actively incorporate strategies for asking and answering questions. a response. In QAT, teachers move beyond telling students the answers to describing how they developed the questions and how they determined the information needed to answer the questions. Since young adolescents learn through individual experiences (Piaget, 1960), QAT provides students with the opportunity to think about text. As a result, students are active, not passive, learners. A group of students practices Questioning as Thinking strategies. 22 Middle School Journal November 2009 The next several sections discuss the three components of the QAT framework—Think-Alouds, QAR, and Self-Questioning—using examples from Jennifer and Barbara’s classes. Think-Aloud A Think-Aloud is an explicit demonstration of cognition in which a teacher or student shares his thinking while solving a problem, answering a question, or reading a text (Kucan & Beck, 1997). It is a tool teachers use to demonstrate the how and why of applying the framework of QAT. The Think-Aloud demonstrates the steps needed when asking and answering questions and under what conditions the learner should implement them. In a Think-Aloud, the teacher models questioning strategies to provide students with a window into the thinking an expert uses when questioning. The teacher should begin with a text and a question with which students may have some difficulty. If the text is not difficult, the students will function automatically, and they will see the metacognitive activity as something that could hinder functioning (Sternberg, 1998). After choosing an appropriate text and question, the teacher identifies the metacognitive task that students would most likely use and prepares a script of the metacognitive actions students would undertake. A welldeveloped Think-Aloud allows students to construct the understanding they need to use QAT to learn from text. Figure 2 contains the Think-Aloud script Barbara used for studying stars. Notice how she explicitly shares with her students the metacognitive strategies required to actively complete the task. In this model, Barbara explains the purpose of the lesson for both the content area and QAT, and she provides the what, how, and why for implementing QAT. Barbara shares her thoughts about the conditions under which a particular kind of thinking occurs. She then explains how to implement the framework, ending with a statement specifying the actions to be taken. Think-Alouds like the one Barbara modeled are a key strategy for helping students understand the metacognitive nature of questioning. When properly implemented, they can make the curriculum more complex and challenging for students, as teachers have more opportunities to demonstrate effective thinking processes for developing deep understanding of ideas in text. Question Answer Relationships (QAR) When scaffolding students’ thinking about complex content, teachers use the language of QAR (Raphael, 1986). The common vocabulary established through QAR guides students and teachers as they enact the QAT framework and become independent thinkers and learners. Figure 2 Barbara models metacognitive strategies for her students. The first question asks what happens in the process of nuclear fusion. I know this might be an ongoing process, so I’m going to look under the main heading, The Beginning and End of Stars. If I scan that section, I see nuclear fusion in italics, and it says, “As the sphere becomes denser, it gets hotter and the hydrogen changes to helium in a process called nuclear fusion.” Therefore, nuclear fusion must be the process of hydrogen changing into helium due to increased temperatures. By looking at the section headings, I was able to find the correct section and quickly scan the paragraph to find the answer to this Right There question. The next question asks the names of some of the different types of stars. Again, I’m going back to page 590, which I have just read, and I notice the main heading, Different Types of Stars. I scan this paragraph, and I find the sentence that says, “Some types of stars include main-sequence stars, giants, supergiants, and white dwarf stars.” This will answer the Right There question. I quickly scanned the paragraph and found that main-sequence stars, giants, supergiants, and white dwarfs are some different types of stars. Now that we have some introductory information on the life cycle of a star, another thing we need to think about is an effective way to take notes about this material. We have used a lot of different note-taking strategies so far this year. [Barbara displays some of the techniques the class has used.] Which one would make sense for the type of information we are covering? Let’s look at our objective again, which is to know the different stages of the life cycle of a star. We’ve been given a preview to that information in what we have read so far. Since it is going to be a series of steps in the sequence of the life cycle and there is going to be information we need to know about each step, the vocabulary flip chart will be a good way to display the information in a way that will be easy to remember and understand. This way we will be able to see what comes first, second, third, and so on in the sequence, but we will also be able to lift the flap to find out the characteristics of each of the stages. Raphael developed QAR to assist students when responding to questions. The success of QAR has been validated by research across content areas and genres (Raphael & Au, 2005). QAR fits into the QAT framework because it requires students to think about the relationship between the text and the question. It also gives students the tools to identify the type of information needed to answer questions. Raphael (1986) identified two broad categories for finding information to answer questions: In the Book and In My Head. Within each of these categories are two subcategories of questions. In the Book answers are found in a text in response to either Right There questions or Think and Search questions. Right There questions have responses that can be found explicitly in a text, whereas Think and Search questions require students to put together information from multiple paragraphs or chapters. In My Head answers require students to use prior knowledge when responding to questions. This category includes Author and Me questions, which ask students to use prior knowledge with information in the text, and On My Own questions, which do not require any reading of the text. The Think and Search and Author and Me questions encourage students to think within and across texts, thus challenging them to consider implied ideas. QAR gives students a vocabulary to use when talking about their metacognition. Recall the question presented to the science student earlier, “What is a homogeneous mixture?” The student who scans the textbook and finds an answer is using Right There strategies. The student who refers to the experiment in class and puts ideas together from the hands-on experience is using Think and Search strategies. The third student uses Author and Me strategies when she integrates her previous knowledge of a mixture with a text definition of homogeneous. In each instance, the student is engaging in metacognition and using the QAR language to describe his or her thinking. They are engaged in active learning while working with an exploratory curriculum and sharing ideas as part of a learning community. As shown in Figure 3, Barbara uses QAT to provide students with the tools necessary to look deeply at the science content. She begins by introducing common language for discussing the relationships between questions and answers. After reading a section of the text on technology and science, she models QAR. www.nmsa.org 23 QAR is an effective starting point for QAT because it uses a task with which students are comfortable and familiar—responding to questions—and it provides a common language for discussing the ways they monitor and regulate cognition. Most students have experienced situations in which they did not know how to answer a question and knew they would be evaluated based on this question. By beginning instruction of metacognition with the familiar task of answering difficult questions, teachers may get student “buy-in.” The common language provided by QAR gives students and teachers the tools to describe metacognitive thinking. When tackling a difficult question, teachers and students use the language of QAR to describe how the question relates to the text and/or the learner and to understand why particular actions are taken to respond to the question. In short, QAR begins the process of Questioning as Thinking because it helps students to use metacognition with a familiar task and provides the language for doing so. Understanding that experience helps the brain develop (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 1999), Barbara and Jennifer give their students guided practice in reading text, reviewing questions, analyzing the Figure 3 Barbara introduces her students to Questioning as Thinking. Follow along as I read the section on computers and technology on page 22. The first after-reading question asks, “How is technology helpful to scientists?” I think I remember reading that, so I am going to go back to the textbook to see is I can find it. There it is. In the first paragraph it says, “By using technology, life scientists are able to find information and solve problems in new ways. It also allows scientists to get information that wasn’t available previously.” Because I found it right there in the book, this is an In the Book question. The second question asks, “Which tool do you think would be the most important to a life scientist? Why?” Well, the question wants to know what I think, so I’m pretty sure this will be an In My Head question. First, I need to think about all the tools I already know scientists use. I know they use lots of measuring equipment like meter sticks, balances, and graduated cylinders. They also use microscopes, computers, and dissecting equipment. Of these tools, I think the microscope would be the most important, because without that, we wouldn’t know very much about microscopic organisms like bacteria, viruses, and other germs. If we didn’t know about these things, we would not be able to prevent the spread of many communicable diseases. All of this information came from my head, therefore, this is an In My Head question. 24 Middle School Journal November 2009 relationship between the text and the question, and describing the thinking used to respond to the question. For instance, in Figure 4 Jennifer guides students through a metacognitive analysis of questions as they read an article about how to read content on a website. As she does this, she engages her students in active learning that will help them tackle challenging curriculum using QAT. Self-Questioning The QAR strategy gives students the metacognitive tools and language for answering questions; but answering Figure 4 Jennifer guides her students in Questioning as Thinking as she explains a reading assignment. Now we’re going to look at the reading selection on page 159. As always, there are questions printed within this selection. Let’s read those questions before you begin reading. First of all, notice the location of the first two questions. Based on where the questions are, what does this tell you about where you will find the answers? Since they are printed on the picture of the web page, you can expect to find the answers here on the web page. According to your QAR brochure, text organization will help you answer Think and Search questions. Number one asks, “Which of the links below would you click to see an overview of the entire NOVA site?” How will you answer this question? Where might you look for information that will help you answer it? [Class discusses answers to the questions.]Have any of you taken advantage of a website’s site map before? If you did not know about site maps, you would most likely have to think and search for the answer. The second question asks, “Where do you think you would click to find information about the history of movie special effects?” Once again, where you look for this answer will depend on your background knowledge of navigating a website. As with the last question, if you have experience with websites this will be an On My Own question; if you do not, it will be an Author and Me question. Question number three asks, “Can it be proved that ‘virtual humans’ are better than live actors? Why, or why not?” What do you think? [Class discusses answers to the questions.] What are the key words in this question? Remember, this chapter also focuses on fact and opinion. It asks if it can be proved. Does that sound like they want fact or opinion? Facts and being proved go together, so that would rule out an In My Head QAR. Now we know the answer will be an In the Book QAR – either Right There or Think and Search. I’ll leave that for you to decide as you answer that question. I’d also like you to tell which QAR you used when you do answer number three. Be sure to explain how you made your decision. questions is not enough. Students need to learn to selfquestion when independently reading text, listening to a lecture, or participating in a hands-on experience. As teachers help students learn to use metacognitive skills, they empower students to take charge of their learning from text. Self-questioning is a research-based practice (Duke & Pearson, 2002; Sternberg, 1998) that helps students independently monitor and regulate their thinking. They monitor cognition by asking questions such as “Does that make sense?” and “What is my learning goal?” These questions help students track their learning. Students regulate their thinking by asking and answering questions such as, “How can I relate this information to what I already know?” and “What do I need to do to remember the ideas presented?” The answers to these questions inform the learner of the metacognitive tasks necessary for learning. Both types of questions—monitoring and regulating—lead learners beyond acquiring simple factual information toward deep understanding. Students come to realize that learning requires thinking and that thinking is stimulated by the kinds of questions we ask. Returning again to the science example, the class is conducting an experiment in which they have two glasses—one that contains oil and water and one that contains water mixed with dissolved sugar. The glass containing water and sugar represents a homogenous mixture because it is uniform in composition and appearance, whereas the glass containing water and oil is heterogeneous because of the visible difference in the substances. When the students observe the glasses, they should ask, “What do I know about homogeneous mixtures, and what am I learning in this experiment?” This question should stimulate the use metacognitive strategies to monitor and regulate learning. A student who uses QAT recognizes that this Author and Me question requires him to connect his textbook knowledge of mixtures to the visual text of the experiment. In addition, as he monitors his learning, he evaluates his understanding of the texts to develop a personal interpretation of the types of mixtures, using the question as a guide. Notice how the language of QAR helps the student regulate strategy use and actively engage in the material. Using QAR, the student can review any question he is asked to determine if the source of his response comes from the experiment (Right There), his prior knowledge (On My Own), or a combination of the two (Author and Me). A teacher guides students through self-questioning during a lesson. In a QAT classroom, the student faced with the mixture experiment would be asked to develop questions that would aid in her understanding of the types of mixtures. She would also be asked to develop a definition of mixtures that demonstrates understanding. In short, using QAT leads to inquiry-oriented instruction and the expectation that students will think and learn independently. A teacher might guide the student by asking her if her questions required him to think deeply about mixtures (Think and Search or Author and Me), or if they led her to surface definitions (Right There). Self-questioning and the language of QAR are scaffolds and tools within the QAT framework that enable students to engage in metacognition. QAR provides the language and promotes student buy-in, www.nmsa.org 25 Instruction in QAT should enable students to transfer their metacognitive skills to new situations. while self-questioning gives learners the tools to be independent. In Figure 5, Barbara introduces her students to SelfQuestioning. Notice how she plans for instruction in the asking questions stage of QAT by setting a purpose for student involvement and providing guided practice for students to implement QAT. Instructing students in QAT As Barbara and Jennifer demonstrated in the vignettes, instruction in QAT requires teachers to model metacognition, teach the QAR language, instruct students in asking questions, and lead students to be actively engaged within a community of collaborative, metacognitive learners. The teacher must remember to guide students through the process, closely monitoring their progress and only providing support when necessary (Pressley, 2002). The teacher must allow ample time for students to learn how to use the framework and guide them in becoming independent learners. This can occur in multiple steps, such as working with the whole class, having students work in small groups, and using prompts to help students respond to questions. Figure 6 shows how Jennifer guides students to engage in metacognition during QAT. Notice how the written prompts guide students through the metacognitive actions needed to respond to the questions. Throughout the framework, students engage Figure 5 Barbara guides her students through Questioning as Thinking in a lesson on protists and fungi. I want you to think about all the questions you asked yourself before you came into my class today. I think you will be surprised at the number of questions you asked without even realizing you asked a question. [Barbara generates a list of questions on the board that she asked herself or the students asked themselves that day, emphasizing the number of questions we ask ourselves without really thinking about it.] Now I want you to think about our overall goal for this unit: What are the general characteristics of protists and fungi? In order to answer this question, what do you think you will have to know? [Barbara writes a list of ideas on the board that she and her students generate, emphasizing the connection between the list on the board and the basic life processes of all living things that were studied earlier in the year.] [Barbara explains the strategy she uses to guide students through QAT.] Students are given a typed list of all the main headings and subheadings from this unit. They work in groups of three or four to write questions based on these headings and subheadings. This task gets their minds thinking about the information in the unit without giving them the entire section to read, and it engages them in the questioning mode of thinking. After they have generated a list of questions for each section, we get together as a class and share all the questions the class generated. The students should see relationships between the questions they asked and the questions that came from other groups. Next, I help them make connections to an earlier activity in which we brainstormed ideas about what we would need to know to identify the general characteristics of protists and fungi. 26 Middle School Journal November 2009 They should see a direct correlation between what we need to know and what the textbook is going to tell us. Then we get into the actual reading of the text. We read section one on protists together. I stop after each heading or subheading and ask a question that came to mind as I was reading. For example, in the General Characteristics section I wondered, what makes protists different from the other kingdoms? The question is looking for the differences between protists and the other kingdoms. I think I remember reading something about this in the second paragraph. I am going to scan the paragraph and see if I can find any of the key words. In the second line, it says, “other kingdoms,” so I will read this more carefully, and it says, “unlike fungi, plants, and animals, protists do not have specialized tissues.” Therefore, this is a Right There question. What makes a protist different from the other kingdoms? They do not have specialized tissues. As I read the next section under the heading Protists and Food and the subheading Producing Food, I wondered where a protist producer would live. It doesn’t say it directly in the text. The text does tell me that since they are producers, they make their own food. It also says that the chloroplasts collect energy from the sun to carry out that process. That leads me to believe that protist producers must live in areas that receive a lot of light. They would not be able to live in a cave, because it would be too dark. So, I used some information from the text and what I know about where light is located to figure out a possible answer to this question. This must be an Author and Me question. I am going to keep this question in mind as I continue reading, and maybe it will give me a more detailed answer later on. in Think-Aloud as they share their thinking about asking and answering questions. When students engage in deep, meaningful discussion as they question texts, they have the opportunity to reflect on the thinking processes of their peers as well as that of their teacher. As this discussion occurs, it creates a learning community centered on thinking and learning complex curriculum. After students are guided through the QAT framework, they need opportunities to demonstrate their thinking independently. These opportunities should take place over a series of texts and situations. Moreover, instruction in QAT should enable students to transfer their metacognitive skills to new situations beyond those provided by the individual teacher in the classroom. Jennifer and Barbara provide multiple opportunities for students to build metacognitive skills. They instruct students in the application of the QAT framework across a variety of content texts at various levels of difficulty. When their students are able to apply the framework and articulate their thinking about text, they are demonstrating metacognitive skills that will support them in their development as independent learners. Conclusion The QAT framework melds three strategies—ThinkAloud, QAR, and Self-Questioning—into a unified approach for asking and answering questions during instructional activities. When teaching students to use QAT, the teacher guides them in becoming active learners who self-question. QAT provides students with a framework for learning that transcends the disciplines and departmental divisions of the school. When implemented on a school-wide basis, students internalize the QAT framework as a process for comprehending texts, regardless of their complexity. The framework gives students and teachers a common language to use when talking about their metacognition, and it enables students Figure 6 Guiding students during Questioning as Thinking (QAT) Question Highly supportive clues to help you use Questioning as Thinking Moderately supportive clues to help you use Questioning as Thinking Minimally supportive clues to help you use Questioning as Thinking • Develop a Think and Search Stop reading at the end of paragraph 4 and ask a question that helps you remember the points made by the author in support of his beliefs that hunting animals for food is acceptable. • Develop a Think and • Develop a Think and Search Search question. • Scan the text for ideas supporting hunting. • Put together the ideas presented. • Create a response to your question. question. • Put together the ideas presented. • Create a response to your question. After reading the piece, explain why you agree or disagree with the statement “Killing animals is acceptable if you are going to eat the meat from the animal?” • This is an Author and Me • This is an Author and Me question • Scan the text to discover what the author says. • Analyze the author’s comments. • Compare/Contrast the author’s comments to your own beliefs. • Develop a response that includes your beliefs and the author’s beliefs. question. • Compare/Contrast the author’s comments to your own beliefs. • Develop a response that includes your beliefs and the author’s beliefs. question. • Create a response to your question. • This is an Author and Me question. • Develop a response that includes your beliefs and the author’s beliefs. www.nmsa.org 27 to become empowered, more engaged, and increasingly self-directed in their learning (Abdullah, 2001). Extensions 1. How does Questioning as Thinking compare to instructional strategies you currently employ in your classroom? 2. How will you make your students aware of the Question Answer Relationships in the lessons you will teach this week? What kinds of metacognitive strategies will you teach to help guide your students’ thinking? To further explore questioning in middle grades classrooms, read “Questioning Techniques of Fifth and Sixth Grade Reading Teachers in the September 2005 issue of MSJ. References Abdullah, M. H. (2001). Self-directed learning [ERIC digest No. 169]. Bloomington, IN: ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading, English, and Communication. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED459458) Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Costa, A. (1985). How can we recognize improved student thinking?” In A. Costa (Ed.), Developing minds: A resource book for teaching thinking, (pp. 288–290). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Costa, A. L. (Ed.). (1991). Developing minds: A resource book for teaching thinking (rev. ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Duke, N., & Pearson, P. D. (2002). Effective practices for developing reading comprehension. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed.) (pp. 205–242). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Hester, J. (1994) Teaching for thinking: A program for school improvement through teaching critical thinking across the curriculum. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press. Kellough, R. D., & Kellough, N. G. (2008). Teaching young adolescents: Methods and resources for middle grades teaching (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall. Kucan, L., & Beck, I. L. (1997). Thinking aloud and reading comprehension research: Inquiry, instruction, and social interaction. Review of Educational Research, 67(3), 271–299. Midgley, C., Anderman, E., & Hicks, L. (1995). Differences between elementary and middles school teachers and students: A goal theory approach. Journal of Early Adolescence, 15(1), 90–113. Neufeld, P. (2005). Comprehension instruction in content area classes. The Reading Teacher, 59(4), 302–312. Piaget, J. (1960). The child’s conception of the world. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press. Pressley, M. (2002). Metacognition and self-regulated comprehension. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (pp. 291–309). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Raphael, T. E. (1986). Teaching question answer relationships, revisited. The Reading Teacher, 39(6), 516–522. Raphael, T. E., & Au, K. (2005). QAR: Enhancing comprehension and test taking across grades and content areas. The Reading Teacher, 59(3), 206–221. Rice, R. P., & Dolgin, K. G. (2005). The adolescent: Development, relationships, and culture (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. Schraw, G. (2002). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. In H. J. Hartman (Ed.), Metacognition in learning and instruction: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 3–16). Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Sternberg, R. J. (1998). Metacognition, abilities, and developing expertise: What makes an expert student? Instructional Science, 26, 127–140. Nance S. Wilson is an assistant professor in the department of teaching and learning principals at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. E-mail: nwilson@mail.ucf.edu Linda Smetana is an associate professor in the department of educational psychology at California State University-East Bay. E-mail: linda.smetana@csueastbay.edu Middle Grades Assessment Measure. Evaluate. Improve. The 16 characteristics of This We Believe: Keys to Educating Young Adolescents serve as the basis for National Middle School Association’s Middle Grades Assessment. This affordable, research-based, online assessment gives you data you can use to effect positive change for your students and faculty. For more information, visit www.nmsa.org/schoolassessment 28 Middle School Journal November 2009